Whitchurch, Shropshire

Whitchurch is a market town in northern Shropshire, England. It lies 2 miles (3 km) east of the Welsh border, 2 miles south of the Cheshire border, 20 miles (30 km) north of the county town of Shrewsbury, 20 miles (30 km) south of Chester, and 15 miles (24 km) east of Wrexham. At the 2011 Census, the population of the town was 9,781.[1] Whitchurch is the oldest continuously inhabited town in Shropshire.[2] Notable people who have lived in Whitchurch include the composer Sir Edward German, folk musician Will Vaughan and illustrator Randolph Caldecott.

| Whitchurch | |

|---|---|

Black Bear Inn, at the junction of Church Street and High Street | |

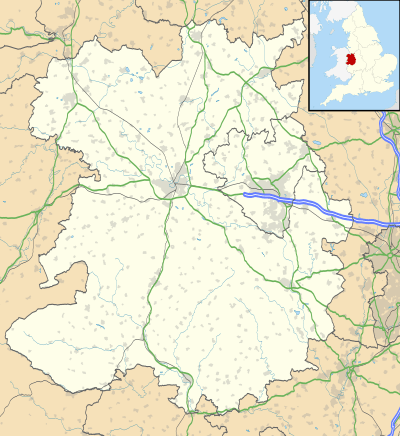

Whitchurch Location within Shropshire | |

| Population | 9,781 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SJ541415 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Whitchurch |

| Postcode district | SY13 |

| Dialling code | 01948 |

| Police | West Mercia |

| Fire | Shropshire |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

History

Early times

There is evidence from various discovered artifacts that people lived in this area about 3,000 BC. Flakes of flint from the Neolithic era were found in nearby Dearnford Farm.[3]

Roman times

Originally a settlement founded by the Romans about AD 52–70 called Mediolanum (lit. "Midfield" or "Middle of the Plain"), it stood on a major Roman road between Chester and Wroxeter. It was listed on the Antonine Itinerary but is not the Mediolanum of Ptolemy's Geography, which was in central Wales. Local Roman artefacts can be seen at the Whitchurch Heritage Centre.[4]

In 2016, archaeologists discovered the remains of a Roman wooden trackway, a number of structural timbers, a large amount of Roman pottery and fifteen leather shoes during work on a culvert in Whitchurch.[5] In 2018, a collection of 37 small Roman coins was unearthed at Hollyhurst near Whitchurch. The small denomination, brass or copper alloy coins, known as Dupondii and Asses, were from the reign of the Emperor Trajan, AD 98-117. Some dated back to between AD 69-79 from the time of Emperor Vespasian.[6]

Middle Ages

In 1066, Whitchurch was called Westune ('west farmstead'), probably for its location on the western edge of Shropshire, bordering the north Welsh Marches. Before the Norman conquest of England, the area had been held by Harold Godwinson. After the conquest, Whitchurch's location on the marches would require the Lords of Whitchurch to engage in military activity.[7] There was a castle at Whitchurch, possibly built by the same Earl of Surrey,[8] which would predate the birth of Ralph. The Domesday Book estimates that the property was worth £10 annually, having been worth £8 in the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042–1066).

By the time it was recorded in the Domesday Book (1086), Whitchurch was held by William de Warenne, 1st Earl of Surrey,[7] and Roger de Montgomery.[9] It was part of the hundred of Hodnet.[10]

The surrounding hamlets became townships and Dodtune ('the settlement of Dodda's people') is now fully integrated into Whitchurch as Dodington. The first church was built on the hill in AD 912. After the Norman Conquest a motte and bailey castle and a new white Grinshill stone church were built. Westune became Album Monasterium ('White Church'). The name Whitchurch is from the Middle English for "White Church", referring to a church constructed of white stone in the Norman period. The area was also known as Album Monasterium and Blancminster,[7] and the Warennes of Whitchurch were often surnamed de Albo Monasterio in contemporary writings.[11] It is supposed that the church was built by William de Warenne, 1st Earl of Surrey.[12]

In 1377 the Whitchurch estates passed to the Talbot family. It was sold by the Talbots to Thomas Egerton, from whom it passed to the earls of Bridgwater and eventually to Earl Brownlow.[13]

The town was granted market status in the 14th century. The replacement third church collapsed in July 1711 and the present Queen Anne parish church of St Alkmund was immediately constructed to take its place. It was consecrated in 1713.

Lords of Whitchurch

William fitz Ranulf is the earliest individual of the Warenne family recorded as the Lord of Whitchurch, Shropshire, first appearing in the Shropshire Pipe Roll of 1176.[7] In 1859, Robert Eyton considered it likely that Ralph, son of William de Warenne, 2nd Earl of Surrey, was the father of William and that he first held that title.[14] However, other theories have been put forward.[15]

Later history

During the reign of Henry I in the 12th century, Whitchurch was in the North Division of Bradford Hundred which by the 1820s was referred to as North Bradford Hundred.[16] In the 18th Century many of the earlier timber-framed buildings were refaced in the more fashionable brick. New elegant Georgian houses were built at the southern end of the High Street and in Dodington.

As dairy farming became more profitable Whitchurch developed as a centre for Cheshire cheese production. Cheese fairs were held on every third Wednesday when farm cheeses were brought into town for sale. Cheese and other goods could be easily transported to wider markets when the Whitchurch Arm of Thomas Telford's Llangollen Canal was opened in 1811. The railway station was opened in 1858 on the first railway line in North Shropshire, running from Crewe to Shrewsbury.

On 23 November 1981, an F1/T2 tornado passed through Whitchurch as part of the record-breaking nationwide tornado outbreak on that day.[17] The Whitchurch tornado was the longest-lived tornado of the entire outbreak, having first touched down 35 miles away in the south Shropshire village of Norbury. After passing through Whitchurch, the tornado dissipated.

Governance

Town

Whitchurch has its own town council which is responsible for street lights, parks and the civic centre which is located in the centre of the town. The council organises various events throughout the year including markets and the Christmas Lights.

County

The town is part of Shropshire Council which is the local authority for Shropshire (excluding Telford and Wrekin). It is a unitary authority, having the powers of a non-metropolitan county and district council combined. The residents of Whitchurch elect three councillors to this council.

National

The town is located within the North Shropshire parliamentary constituency. This constituency is largely rural with the main urban centres being Oswestry, Market Drayton and Whitchurch. It has been in existence since 1832 although it was abolished in 1885 but re-established in 1983. The residents of the constituency elect one MP who since 1997 has been Owen Paterson, a Conservative.

Landmarks

Buildings

There are currently over 100 listed buildings in Whitchurch, including the churches detailed in the religion section lower down.[18]

In the picture to the left is the street named Bargates. At the top on the left is St Alkmund's Church (rebuilt 1712–13). This is followed by the former almhouses by Samuel Higginson (1697). This is followed by the former girls' school founded by Jane Higginson (1708) and then the old Whitchurch Grammar School which was founded in 1548. The grammar school building dates from 1708 (Grade II listed) and was latterly used as an infants' school. Further buildings were added in 1848 and 1926. All have now been converted into apartments.[19]

Streets

The street names in the town centre reflect the changing history of the town.

- Roman: Pepper Street – a common name in former Roman settlements. It is a derivation of the Roman Via Piperatica – the street on which pepper and spices were sold.[20]

- Norse: Several streets end in 'gate' which is Norse for street (e.g., Watergate, Highgate, Bargates). Others refer to the castle which was located here (e.g., Castle Hill or Yardington referring to the castle yard).

- Modern: Some refer to local industry (e.g., Claypit Street, clay was used for making bricks; Mill Street, named after the local water mill; and Bark Hill, bark was used for tanning.

Place names

The areas of Whitchurch have interesting names. These include:

Transport

Roads

Whitchurch has roads to Wrexham, Nantwich, Chester and Shrewsbury; the A41/A49 bypass opened in 1992. There are bus services from Whitchurch to surrounding towns including Chester, Nantwich, Wrexham and Shrewsbury.[23]

Railway

Whitchurch railway station is on the former London and North Western (later part of the LMS) line from Crewe down the English side of the Welsh border (the Welsh Marches Line) toward Cardiff. However, Whitchurch was once the junction for the main line of the Cambrian Railways, but the section from Whitchurch to Welshpool (Buttington Junction), via Ellesmere, Whittington, Oswestry and Llanymynech, closed on 18 January 1965 in favour of the more viable alternative route via Shrewsbury. Whitchurch was also the junction for the Whitchurch and Tattenhall Railway or Chester to Whitchurch branch line, another part of the London and North Western, running via Malpas. The line closed to regular services on 16 September 1957, but use by diverted passenger trains continued until 8 December 1963.

Canals

Whitchurch has its own short arm of the Llangollen Canal and the town centre can be reached by a walk of approximately 1 mile along the Whitchurch Waterways Country Park, the last stage of the Sandstone Trail. The Whitchurch Arm is managed by a charity group of local volunteers.[24]

Economy

Historically the town has been the centre of cheese-making. Today Belton Cheese continues to be a major employer. It has been in existence since 1922.[25]

The major employer in the town now is Grocontinental, a logistics provider to the food industry, which employs over 350 people.[26] This family firm which was established in 1941 was taken over by the Dutch multinational AGRO Merchants in 2017.[27]

The town also provides a range of services for the surrounding countryside of the North Shropshire Plain. Most of the retail stores are concentrated in the High Street and Green End. There is a Tesco supermarket in the town centre (White Lion Meadow), a smaller Lidl store and a larger Sainsbury's supermarket in London Road.

There are several speciality food shops including Powell's Pork Pie shop, which has been selling traditional pork pies for four generations and won the Great British Pork Pie Bronze Award.[28] On the High Street is located Walker's Bakery and Cafe which sells bread and cakes which are baked on the premises.

The town was the home of the J. B. Joyce tower clocks company, established in 1690, the earliest tower clock-making company in the world,[29] which earned Whitchurch a reputation as the home of tower clocks. Joyce's timepieces can be found as far afield as Singapore, Kabul and Cape Town (see right). The firm also helped to build Big Ben in London. However, J. B. Joyce have now left and an auction house has moved into the building.[30]

By rail Whitchurch is within commuting distance of Manchester (about one hour north) and Shrewsbury (30 minutes south).

Arts and culture

There is a wide range of arts and culture activities, festivals and facilities and societies in Whitchurch.

Cultural venues and facilities

- Whitchurch Civic Centre – hosts various performances throughout the year. It also contains a public library.[31]

- Whitchurch Heritage Centre.[32]

- Talbot Theatre – located in the Leisure Centre at the Sir John Talbot School.[33] It offers regular theatrical and musical events as well as film.

- Doodle Alley.[34]

- Whitchurch Amateur Operatic and Dramatic Society.[35]

- Whitchurch Little Theatre Group on Facebook.

Festivals

The periodic televised Sir Edward German Music Festival, hosted by St Alkmund's and St John's churches, also uses Sir John Talbot's Technology College as a venue. The first festival was held in 2006 and the second in April 2009. Participants have included local choirs and primary schools, including Prees, Lower Heath and White House, as well as internationally known musicians and orchestras.

Historic cultural activities

On 19 January 1963 The Beatles played in the old Town Hall Ballroom (now the location of the town Civic Centre). That night a recording of the group appeared on the television show Thank Your Lucky Stars, an appearance which changed their fortunes. Please Please Me had just been released as a single.[38]

Sport

Whitchurch Rugby Club[39] currently competes in the Midlands 1 West league, the sixth tier of English rugby. Founded in 1936, the club plays at Edgeley Park and has a full complement of mini rugby and junior teams as well as under-19s (Colts), a ladies team and four senior teams. In 1998/99, it was promoted to National Division Three North, a position it maintained until the 2002/03 season.

The local football club, Whitchurch Alport F.C., was founded in 1946. It is named after Alport Farm in Alport Road, which was the home of local footballer, Coley Maddocks, killed in the Second World War.[40] They were founder members of the Cheshire Football League and played in that league until 2012, before a spell in the Mercian Regional Football League. Since 2015, Whitchurch Alport has played in the North West Counties Football League premier Division.[41]

The Chester Road Bowling Club has been in existence since 1888. It was originally a bowling and tennis club. It has over 160 members and fields 23 teams (mostly men and women) in six different leagues.[42] Another bowling club, the Whitchurch and District, was founded in 1924.

The Whitchurch Swimming Centre is located in the centre of the town. It has a 25-metre (82 ft) pool.[43] Whitchurch Leisure Centre is located at the Sir John Talbot School on the edge of town. It offers a range of exercise facilities and classes.[44]

The Whitchurch Walkers is an active group of residents interested in walking and the protection of footpaths. It organises a range of events, including an annual walking festival.[45] The Sandstone Trail starts/end at the Whitchurch arm of the canal. It forms part of the Shropshire Way.[46]

On the northern edge of the town is the Macdonald Hill Valley Hotel, which has a fitness centre, a swimming pool and two golf courses.[47]

Since August 2019, Alderford Lake, just to the south of the town, has hosted a parkrun, which is a free, weekly timed 5 km run/walk, every Saturday morning at 9am.

Education

Whitchurch has a long history of schools. Whitchurch Grammar School was established in 1548 by Rev Sir John Talbot, the Rector of Whitchurch in the 1540s. The school opened in 1550 making it one of the oldest schools in England. It was restricted to boys. Next door to it a school for girls was established. They closed in 1936 and became part of the new Sir John Talbot’s School which is located on the edge of the town. It has about 500 students aged 11–18. This school is now part of the Marches Academy Trust.[48]

The main primary school in the town is Whitchurch CE Junior School, which has about 300 pupils aged 7–11.[49] Younger children attend Whitchurch CE Infant and Nursery School.[50] The White House School, an independent primary, lies on the edge of the town. It was founded in 1945 and has about 100 pupils.[51]

There is an active branch of the University of the Third Age with over 350 members.[52]

Religion

The town's most prominent place of worship is St Alkmund's Anglican parish church, built in 1712 of red sandstone on the site of a Norman church. It is a Grade I listed building. St Catherine's in Dodington was built in 1836 as a chapel of ease for St Alkmund's, which at that time was over-crowded. It is Grade II listed,[53] but ceased to be used for worship in the 1970s. It featured in the 1995 BBC One Foot in the Past programme,[54] when it was being used as a builder's store. It has now been converted into apartments.

St John's Methodist Church, built in 1879, stands on the corner of St John's Street and Brownlow Street. It is Grade II listed.[55] The Wesleyan Chapel in St Mary's Street, which opened in 1810, closed shortly after St John's opened and is now the Whitchurch Heritage Centre. The Primitive Methodist Chapel in Castle Hill opened in 1866 and closed in the 1970s. John Wesley preached in Whitchurch on 18 April 1781.[56] The Dodington United Reformed (formerly Congregational) Church (built in 1815 and Grade II listed[57]) is now closed, as is the Dodington Presbyterian Chapel (built in 1707). A Baptist chapel was built in Green End in 1820 but closed in 1939. It is now an antique showroom.[58]

St George's Catholic Church has been located in Claypit Street since 1878.[59]

Whitchurch Cemetery includes 91 Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) burials: 24 from the First World War, in scattered plots, and 67 from the Second World War, mostly grouped in a CWGC section; 52 of the latter are Polish or Czechoslovak, as No. 4 Polish General Hospital was at Iscoyd Park just over the border in Wales.[60]

Notable people

In birth order:

- Sir Henry Percy (Sir Harry Hotspur) (1364–1403), killed at the Battle of Shrewsbury[61] and buried in Whitchurch, only for his body to be later exhumed and quartered.

- Sir John Talbot (c. 1384–1453), a warrior commander who in 1429 fought French armies inspired by Joan of Arc.[62] He was born at Black Mere Castle; the site is now a scheduled monument named Blakemere Moat[63] northeast of Whitchurch along Black Park Road. His remains are buried under the porch of St Alkmund's Church.[64] Talbot is a major character in Shakespeare's Henry VI, Part I.

- Rev. Sir John Talbot (c. 1490–1549), Rector of Whitchurch in 1540s, founded Whitchurch Grammar School in 1548. The school opened in 1550.[65] The school closed in 1938 when it moved to its present location as the Sir John Talbot’s School.

- Abraham Wheelock (1593–1653), linguist,[66] first Adams Professor of Arabic at the University of Cambridge

- Nicholas Bernard (c. 1600–1661), pamphleteer,[67] former dean of Ardagh in Ireland and chaplain to Oliver Cromwell, was appointed rector of the parish in 1660 and buried at St Alkmund's Parish Church.

- Philip Henry (1631–1696), nonconformist clergyman[68] and Vicar of nearby Worthenbury. His son Matthew attended Whichurch Grammar School.

- Joseph Bromfield (1744–1824), notable English plasterer[69] and architect

- John Pridden (1758–1825), English cleric[70] and antiquary.

- Reginald Heber (1783–1826), Rector of Hodnet[71] and Bishop of Calcutta attended Whitchurch Grammar School

- Thomas Corser (1793–1876), literary scholar[72] and Church of England clergyman.

- Randolph Caldecott (1846–1886), illustrator,[73] lived in the town, the town's buildings feature in his work.

- Sir Edward German (1862–1936), composer, was born in the town.[74] in what is now a pub: the Old Town Hall Vaults. He is buried in the local cemetery and commemorated in a local street.

- Thomas Oakley (1879–1936), working-class Conservative politician, MP[75] for The Wrekin 1924/1929

- Percy Newton (1904–1993), professional footballer[76]

- Lucy Appleby MBE (1920–2008), traditional cheesemaker[77]

- Ken Dodd OBE (1928 - 2018), comedian and singer; although he lived in Knotty Ash he kept a country house near Whitchurch for fifty years.[78]

- Lorna Sage (1943–2001), literary critic and author,[79] was born in Whitchurch and attended the girls' high school.[80]

- Stuart Mason (1948–2008), professional footballer,[81] was born in Whitchurch and began his career with Whitchurch Alport.

- Owen Paterson (born 1956 in Whitchurch) former environment secretary and Conservative MP[82] for North Shropshire since 1997

- Kate Long, (born 1964) novelist, author of The Bad Mother's Handbook, moved to Whitchurch in 1990.[83]

- Christina Trevanion (born 1981), auctioneer and television[84] personality.

References

- "Area: Whitchurch Urban (Parish). Key Figures for 2011 Census: Key Statistics". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- "Whitchurch town guide". BBC. 14 April 2005. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- Barton, Joan (2001) A Millennium History of Whitchurch. Whitchurch History and Archeology Group.

- "Whitchurch Heritage Centre". Shropshire Tourism. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- "Archaeologists unearth Roman remains in Whitchurch". Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- "Hoard of Roman coins and brooch found in Shropshire declared treasure". Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- Anderson, John Corbet. Shropshire, Its Early History and Antiquities. by John Corbet Anderson. Willis and Sotheran, 1864, pp. 402–04,

- Botfield, Beriah. Collectanea Archæologica: Shropshire Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1862 p45-46

- William Farrer, Charles Travis Clay. Early Yorkshire Charters: Volume 8, The Honour of Warenne. Cambridge University Press, 2013 (originally 1949), p. 37.

- Open Domesday: Hodnet

- Farrer and Clay 2013, p. 36.

- Auden, Thomas, ed. Memorials of Old Shropshire. Vol. 1. Bemrose & sons, limited, 1906. p. 43.

- "Page:EB1911 - Volume 28.djvu/618". Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- Eyton, R. W. (1859). Antiquities of Shropshire. Volume X. London: John Russell Smith. pp. 15–16.

William de Warren, better known as William fitz Ranulf. His relation to the elder line has never been ascertained or surmised. William, second Earl Warren, who died in 1135, is said to have had three sons: William, Reginald, and Ralph. William is well known as his father's successor and the last of the elder male line. Reginald became notorious as Lord of Wirmgay by marriage with its heiress. Of Ralph little has been recorded except his dates. It is consistent to suppose him to be the father of William fitz Ranulf.

- Farrer and Clay 2013, p37-38

- Vision of Britain: Whitchurch (Shropshire)

- http://www.eswd.eu/cgi-bin/eswd.cgi

- "Listed Buildings in Whitchurch Urban, Shropshire". Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- Historic England. "The Old Grammar School, Whitchurch, Shropshire (1056001)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- "Pepper: The King of Spice". Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- "History of Whitchurch". History of Whitchurch. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Geograph". Chemistry Bridge, Whitchurch. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- 'Listing of bus services from Whitchurch'. 30 October 2017

- The Whitchurch Waterway Trust charity. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Belton Farm". Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- "Grocontinental". Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "whitchurch haluage firm". Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Powells Pork Pies". Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Warriors and Worthies". North Shropshire Tourism. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- Trevanion & Dean, ABOUT OUR BUILDING & JOYCE’S CLOCKS retrieved 21 March 2018

- "Whitchurch Civic Centre". Whitchurch Town Council. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Whitchurch Heritage Centre". Whitchurch Heritage Centre. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Whitchurch Leisure Centre". Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Doodle Alley". Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Whitchurch Amateur Operatic and Dramatic Society". Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- "Blackberry Fair". Whitchurch. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Whitchurch Food and Drink Festival". Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Shropshire Star-Beatles autographs from Shropshire concert". Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- Whitchurch Rugby Club

- Francis, Peter (2013). Shropshire War Memorials, Sites of Remembrance. YouCaxton Publications. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-909644-11-3.

- Whitchurch Alport FC Archived 16 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Club Statement (1 August 2012)

- "Chester Road Bowling Club". Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- "Whitchurch Swimming Centre". Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Whitchurch Leisure Centre". Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Whitchurch Walkers". Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Stage 12: Wem to Whitchurch and Ellesmere" (PDF). Shropshire Way. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- "Macdonald Hill Valley Hotel". Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- "Sir John Talbot's School". Marches Academy Trust. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- "Whitchurch CE Junior School". Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- Town site 'Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "White House School". Retrieved 2 November 2017.

- "U3a Whitchurch". Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- https://www.britishlistedbuildings.co.uk/101366532-former-church-of-saint-catherine-whitchurch-urban#.WfyaCCOLRFA.

- "Church of Catherine, Whitchurch". Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Saint Johns Methodist Church". Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "St John's, Whitchurch". Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "United Reformed Church". Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- "Shropshire's history". Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- "Whitchurch - St George Protector of England". Retrieved 30 October 2017.

- "Whitchurch Cemetery". CWGC. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 44, Percy, Henry (1364-1403) retrieved 21 March 2018

- 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, Volume 24, Shrewsbury, John Talbot, 1st Earl of retrieved 21 March 2018

- Blakemere Moat

- "Town Guides – Whitchurch". Shropshire Star. 4 May 2004. Archived from the original on 23 August 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- "Whitchurch". UK Genealogy Archives. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 60, Wheelocke, Abraham retrieved 21 March 2018

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 04, Bernard, Nicholas retrieved 21 March 2018

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 26, Henry, Philip retrieved 21 March 2018

- Archive of Sandford House Hotel, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, retrieved 20 March 2018

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 46, Pridden, John retrieved 20 March 2018

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 25, Heber, Reginald retrieved 20 March 2018

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 12, Corser, Thomas retrieved 20 March 2018

- Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 08, Caldecott, Randolph retrieved 20 March 2018

- "Edward German (1862–1936)". Retrieved 12 April 2008.

- HANSARD 1803–2005 → People (O), Mr Thomas Oakley retrieved 20 March 2018

- MUFC Info.com profile retrieved 20 March 2018

- The Guardian, 30 May 2008, Lucy Appleby retrieved 20 March 2018

- "Shropshire Star-Mystery solved: Why Doddy let the grass grow at his Shropshire country hideaway". Retrieved 4 December 2019.

- The Guardian, 12 January 2001, Lorna Sage, "Past Imperfect" retrieved 20 March 2018

- ODNB entry by Maureen Duffy. Retrieved 22 January 2013. Pay-walled.

- Stuart Mason, Obituary, www.chester-city.co.uk retrieved 20 March 2018

- Record in Parliament, TheyWorkForYou retrieved 20 March 2018

- "Novelists heading to town". Shropshire Star. 27 May 2006. Archived from the original on 29 August 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- BBC, Bargain Hunt, Christina Trevanion retrieved 20 March 2018

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Whitchurch, Shropshire. |