Warmia

Warmia (pronounced: VAR-mya, Polish: Warmia, Latin: Varmia, German: ![]()

Warmia | |

|---|---|

Historical region | |

Coat of arms | |

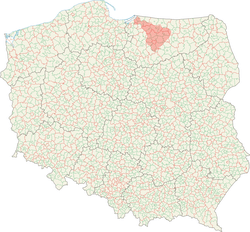

The historical region of Warmia (shown in pink) within the borders of present-day Poland | |

| Country | |

| Seat | Lidzbark |

| Cities | Olsztyn, Braniewo, Reszel, Frombork |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,500 km2 (1,700 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 350,000 |

| • Density | 78/km2 (200/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Warmia is currently the core of the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (province). The region covers an area of around 4,500 km2 and has approximately 350,000 inhabitants. Important landmarks include the Cathedral Hill in Frombork (Frauenburg), where Nicolaus Copernicus elaborated the heliocentric theory, the bishops' castles at Olsztyn and Lidzbark, the medieval town of Reszel (Rößel) and the sanctuary in Gietrzwałd (Dietrichswalde), a site of Marian apparitions. Geographically, it is an area of many lakes and lies at the upper Łyna river and on the right bank of Pasłęka, stretching in the northwest to the Vistula Bay. Warmia has a number of architectural monuments ranging from Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque to Classicism, Historicism and Art Nouveau.

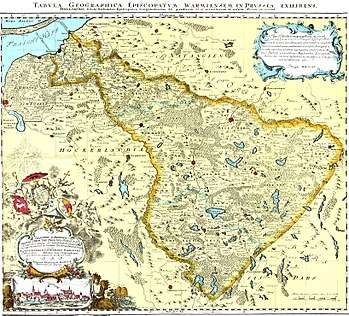

Warmia is part of a larger historical region called Prussia, which was inhabited by the Old Prussians and later on was populated mainly by Germans and Poles.[1] Warmia has traditionally strong connections with neighbouring Masuria, but it remained Catholic and belonged to Poland between 1454/1466 and 1772, whereas Masuria became part of the Duchy of Prussia and became predominantly Protestant. Warmia has been under the dominion of various states over the course of its history, most notably the Old Prussians, the Teutonic Knights, the Kingdom of Poland and the Kingdom of Prussia. The history of the region is closely connected to that of the Archbishopric of Warmia (formerly, Duchy of Warmia). The region is associated with the Prussian tribe, the Warmians,[2] who settled in an approximate area. According to folk etymology, Warmia is named after the legendary Prussian chief Warmo, and Ermland derives from his widow Erma.

History

Early times

By the early Middle Ages the Warmians, an Old Prussian tribe, inhabited the area.

Beginning of the Northern Crusades

In the 13th century the area became a battleground in the Northern Crusades. Having failed to gather an expedition against Palestine, Pope Innocent III resolved in 1207 to organize a new crusade; beginning in 1209, he called for crusades against the Albigenses, against the Almohad dynasty of Spain (1213), and, also around that time, against the pagans of Prussia.[3] The first Bishop of Prussia, Christian of Oliva, was commissioned in 1209 to convert the Prussians, at the request of Konrad I of Masovia (duke from 1194 to 1247).

Teutonic Order

In 1226 Duke Konrad I of Masovia invited the Teutonic Knights to Christianize the pagan Prussians. He supplied the Teutonic Order and allowed the usage of Chełmno Land (Culmerland) as a base for the knights. They had the task of establishing secure borders between Masovia and the Prussians, with the assumption that conquered territories would become part of Masovia. The Order waited until they received official authorisation from the Empire, which Emperor Frederick II granted by issuing the Golden Bull of Rimini (March 1226). The papal Golden Bull of Rieti from Pope Gregory IX in 1234 confirmed the grant, although Konrad of Masovia never recognized the rights of the Order to rule Prussia. Later, the Knights were accused of forging these land grants.

By the end of the 13th century the Teutonic Order had conquered and Christianized most of the Prussian region, including Warmia. The new régime reduced many of the native Prussians to the status of serfs and gradually Germanized them. Over several centuries the colonists, native Prussians and immigrants gradually intermingled.

In 1242 the papal legate William of Modena set up four dioceses, including the Archbishopric of Warmia. From the 13th century new colonists, mainly Germans, settled in the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights (with Warmia) (the Duchy of Prussia, Lutheran from 1525 onwards, granted refuge to Protestant Poles, Lithuanians, Scots and Salzburgers). The bishopric was exempt and was governed by a prince-bishop, confirmed by Emperor Charles IV. The Bishops of Warmia were usually Germans or Poles, although Enea Silvio Piccolomini, the later Pope Pius II, served as an Italian bishop of the diocese.

After the 1410 Battle of Grunwald, Bishop Heinrich Vogelsang of Warmia surrendered to King Władysław II Jagiełło of Poland, and later with Bishop Henry of Sambia gave homage to the Polish king at the Polish camp during the siege of Marienburg Castle (Malbork). After the Polish army moved out of Warmia, the new Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, Heinrich von Plauen the Elder, accused the bishop of treachery and reconquered the region.[4]

Polish Crown

The Second Peace of Thorn (1466) removed Warmia from the control of the Teutonic Knights and placed it under the sovereignty of the Crown of Poland as part of the province of Royal Prussia, although with several privileges.

Soon after, in 1467, the Cathedral Chapter elected Nicolas von Tüngen against the wish of the Polish king. The Estates of Royal Prussia did not take the side of the Cathedral Chapter. Nicholas von Tüngen allied himself with the Teutonic Order and with King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary. The feud, known as the War of the Priests, was a low scale affair, affecting mainly Warmia. In 1478 Braniewo (Braunsberg) withstood a Polish siege which was ended in an agreement in which the Polish king recognized von Tüngen as bishop and the right of the Cathedral Chapter to elect future bishops, which however would have to be accepted by the king, and the bishop as well as Cathedral Chapter swore an oath to the Polish king. Later in the Treaty of Piotrków Trybunalski (December 7, 1512), conceded to the king of Poland a limited right to determine the election of bishops by choosing four candidates from Royal Prussia.[5]

After the Union of Lublin in 1569 Duchy of Warmia was officially directly included as part of the Polish crown within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. At the same time the territory continued to enjoy substantial autonomy, with many legal differences from neighbouring lands. For example, the bishops were by law members of Polish Senat and the land elected MP's to the Sejmik resp. Landtag of Royal Prussia as well as MP's to the Sejm of Poland.

Warmia was under the Church jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Riga until 1512, when Prince-Bishop Lucas Watzenrode received exempt status, placing Warmia directly under the authority of the Pope (in terms of church jurisdiction), which remained until the resolution of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.

Prussia

By the First Partition of Poland in 1772, Warmia was annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia; the properties of the Archbishopric of Warmia were secularized by the Prussian state. In 1773 Warmia was merged with the surrounding areas into the newly established province of East Prussia. Ignacy Krasicki, the last prince-bishop of Warmia as well as Enlightenment Polish poet, friend of Frederick the Great (whom he did not give homage as his new king), was nominated to the Archbishopric of Gnesen (Gniezno) in 1795. After the last partition of Poland and during his tenure as Archbishop of Poland and Prussian subject he was ordered by Pope Pius VI to teach his Catholic Poles to 'stay obedient, faithful, and loving to their new kings', Papal brief of 1795. The Prussian census in 1772 showed a total population of 96,547, including an urban population of 24,612 in 12 towns. 17,749 houses were listed and the biggest city was Braunsberg (Braniewo).

Between 1773 and 1945 Warmia was part of the predominantly Lutheran province of East Prussia, with the exception that the people of Warmia remained largely Catholic. Most of the population of Warmia spoke High Prussian German , while a small area in the north spoke Low Prussian German; southern Warmia was mostly populated by Polish-speaking Warmiaks [6] Warmia became part of the German Empire in 1871.

In 1873 according to a regulation of the Imperial German government, school lessons at public schools inside Germany had to be held in German, as a result the Polish language was forbidden in all schools in Warmia, including Polish schools already founded in the sixteenth century. In 1900 Warmia's population was 240,000. In the jingoistic climate after World War I, Warmian Poles were subject to persecution by the German government. Polish children speaking their language were punished in schools and often had to wear signs with insulting names, such as "Pollack".[8]

After the First World War in the aftermath of the East Prussian plebiscite, carried when Red Army was marching on Warsaw - Polish–Soviet War in 1920, the region remained in Germany, as in the Warmian district of Allenstein (Olsztyn) 86,53% and in the district of Rössel (Reszel) 97,9% voted for Germany. The persecutions of the German governments and militias worsened in the late 1930s when Hitler was in power, and the Poles in Warmia were subject to harsh persecution by German authorities and militias, such as attacks on schools and centers. During World War II Germany sought to suppress all elements of social and political life of the Polish minority in Germany by interning and murdering Polish activists and leaders, including the ones in Warmia. Unlike the rest of Protestant East Prussia, Warmia retained its Catholicism and Catholic-related folk customs, all the way through 1945.

Polish Republic

At the Yalta Conference and Potsdam Conference of 1945, the victorious Allies, at Stalin's demand, divided East Prussia into the two parts now known as Oblast Kaliningrad (in Russia) and the Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship (in Poland), making Warmia part of Poland as part of the so-called Recovered Territories, pending a final peace conference with Germany which eventually never took place.[9] Most of the population was evacuated or fled the advancing Red Army in 1945. Prior to the Potsdam Conference, during the Soviet winter 1945 offensive (Vistula–Oder Offensive), the Red Army overran Warmia.

Olsztyn is the largest city in Warmia and the capital of the Warmian-Masurian Voivedeship. During 1945-46, Warmia was part of the Okreg Mazurski (Masurian District). In 1946 a new voivodeship was created and named the Olsztyn Voivodeship, which encompassed both Warmia and Masurian counties. In 1975 this voivodeship was redistricted and survived in this form until the new redistricting and renaming in 1999 as Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship. The Catholic character of Warmia has been preserved in the architecture of its villages and towns, as well as in folk customs.

Cities and towns

.jpg)

| City | Population (2015)[10] | Granted city rights | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 174,675 | 1353 | |

| 2. | 17,385 | 1254 | |

| 3. | 16,352 | 1308 | |

| 4. | 10,626 | 1395 | |

| 5. | 10,599 | 1329 | |

| 6. | 9,046 | 1313 | |

| 7. | 7,265 | 1364 | |

| 8. | 4,817 | 1337 | |

| 9. | 3,346 | 1338 | |

| 10. | 2,949 | 1312 | |

| 11. | 2,492 | 1385 | |

| 12. | 2,475 | 1310 |

Gallery

- Castles of Warmian Bishops

- Lidzbark Warmiński Castle

- Pieniężno Castle

.jpg) Remains of the Braniewo Castle

Remains of the Braniewo Castle

- Brick Gothic churches of Warmia (examples)

Frombork Cathedral

Frombork Cathedral Saint James Cathedral in Olsztyn

Saint James Cathedral in Olsztyn Collegiate church in Lidzbark Warmiński

Collegiate church in Lidzbark Warmiński Saints Peter and Paul church in Reszel

Saints Peter and Paul church in Reszel- Collegiate church in Dobre Miasto

- Saint Catherine of Alexandria church in Braniewo

People

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473 in Toruń – 1543 in Frombork), mathematician and astronomer

- Stanislaus Hosius (1504 in Krakow – 1579 in Capranica), Polish writer and diplomat, Bishop of Warmia

- Marcin Kromer (1512 in Biecz – 1589 in Lidzbark Warmiński), Polish cartographer, diplomat and historian, personal secretary of Kings of Poland, Bishop of Warmia

- Regina Protmann (1552 in Braunsberg – 1613 in Braunsberg), Polish Roman Catholic, founder of the Sisters of Saint Catherine

- Andrzej Chryzostom Załuski (1650 – 1711 in Dobre Miasto), Polish translator, prolific writer, Bishop of Warmia

- Ignacy Krasicki (1735 in Dubiecko – 1801 in Berlin), leading Polish Enlightenment poet

- Antoni Blank (1785 in Olsztyn – 1844 in Warsaw), Polish painter

- Hugo Haase (1863 in Allenstein – 1919 in Berlin), German socialist politician, jurist and pacifist

- Feliks Nowowiejski (1877 in Wartenburg – 1946 in Poznań), Polish composer, conductor, concert organist and music teacher

- Maximilian Kaller (1880 in Bytom – 1947 in Frankfurt on Main), Roman Catholic Bishop of Warmia

- Erich Mendelsohn (1887 in Allenstein – 1953 in San Francisco), Jewish German architect, known for expressionist architecture

- Hans-Jürgen Wischnewski (1922 in Allenstein – 2005 in Cologne), German SPD politician

- Rainer Barzel (1924 in Braunsberg – 2006 in Munich), German CDU politician

- Georg Sterzinsky (1936 in Warlack – 2011 in Berlin), German cardinal of the Roman Catholic Church and the Archbishop of Berlin

See also

- Prince-Bishopric of Warmia

- Archbishopric of Warmia

- Bishops of Warmia

References

- Linguistic map Poland 1912

- Also called the Warms, Varms, Varmi, Warmians, Varmians.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Crusades Archived 2014-09-17 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 16 March 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "WHKMLA : Royal Prussia : Warmia Stift Feud (Pfaffenkrieg), 1467-1479". www.zum.de. Archived from the original on 4 February 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Nationale Minderheiten und staatliche Minderheitenpolitik in Deutschland im 19. Jahrhundert, Hans Henning Hahn, Peter Kunze, p. 109

- Leon Sobociński, Na gruzach Smętka, wyd. B. Kądziela, Warszawa, 1947, p. 61 (in Polish)

- "Strona główna - Dom Warmiński". Dom Warmiński. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- Geoffrey K. Roberts, Patricia Hogwood (2013). The Politics Today Companion to West European Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9781847790323.; Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1980). The United States and Poland. Harvard University Press. p. 303. ISBN 9780674926851.; Phillip A. Bühler (1990). The Oder-Neisse Line: a reappraisal under international law. East European Monographs. p. 33. ISBN 9780880331746.

- "Lista miast w Polsce (spis miast, mapa miast, liczba ludności, powierzchnia, wyszukiwarka)". polskawliczbach.pl. Archived from the original on 25 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- (in Polish) Erwin Kruk, "Warmia i Mazury", Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie, Wrocław 2003, ISBN 83-7384-028-1