Duchy of Prussia

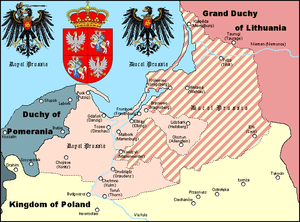

The Duchy of Prussia (German: Herzogtum Preußen, Polish: Księstwo Pruskie) or Ducal Prussia (German: Herzogliches Preußen; Polish: Prusy Książęce) was a duchy in the region of Prussia established as a result of secularization of the State of the Teutonic Order during the Protestant Reformation in 1525.

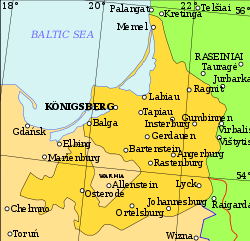

Duchy of Prussia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1525–1701 | |||||||||

The Duchy of Prussia (yellow) | |||||||||

| Status | Fief of the King of Poland (to 1657) Part of Brandenburg-Prussia (from 1618) | ||||||||

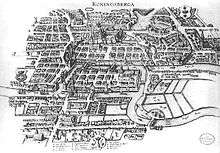

| Capital | Königsberg | ||||||||

| Common languages | Low German, German, Polish, Lithuanian | ||||||||

| Religion | Lutheranism[1] | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | ||||||||

| Duke | |||||||||

• 1525–1568 | Albert | ||||||||

• 1568–1618 | Albert Frederick | ||||||||

• 1618–1619 | John Sigismund | ||||||||

• 1619–1640 | George William | ||||||||

• 1640–1688 | Frederick William | ||||||||

• 1688–1701 | Frederick | ||||||||

| Legislature | Estates | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

| 10 April 1525 | |||||||||

| 1701 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Lithuania Poland Russia | ||||||||

It was the first Protestant state when Albert, Duke of Prussia formally adopted Lutheranism as early as 1525. It was inhabited by a German, Polish (mainly in Masuria) and Lithuanian-speaking (mainly in Lithuania Minor) population. In old texts and in Latin, the term Prut(h)enia refers alike to Ducal Prussia, and the breakaway province of Royal Prussia, and their common predecessor, Teutonic Prussia. The adjectival form of the name was "Prut(h)enic".[2]

In 1525 during the Protestant Reformation, in accordance to the Treaty of Kraków, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights, Albert, secularized the order's Prussian territory, becoming Albert, Duke of Prussia. The new duke established Lutheranism as the first Protestant state church. The land retained its independence, the capital remained in Königsberg (Polish: Królewiec, Lithuanian: Karaliaučius; modern Kaliningrad), while the duke chose the king of Poland, his uncle, as titular liege. The duchy was inherited by the Hohenzollern prince-electors of Brandenburg in 1618; this personal union is referred to as Brandenburg-Prussia. Frederick William, the "Great Elector" of Brandenburg, achieved full sovereignty—less the titular liege-lord—over the duchy under the 1657 Treaty of Wehlau, confirmed in the 1660 Treaty of Oliva. In the following years, attempts were made to return under Polish suzerainty, especially by the capital city of Königsberg, whose burghers rejected the treaties and viewed the region as part of Poland.[3] The Duchy of Prussia was elevated to a kingdom in 1701.

History

Background

As Protestantism spread among the laity of the Teutonic Monastic State of Prussia, dissent began to develop against the Roman Catholic rule of the Teutonic Knights, whose Grand Master, Albert, Duke of Brandenburg-Ansbach, a member of a cadet branch of the House of Hohenzollern, lacked the military resources to assert the order's authority.

After losing a war against the Kingdom of Poland, and with his personal bishop, Georg von Polenz of Pomesania and of Samland, who had converted to Lutheranism in 1523,[4] and a number of his commanders already supporting Protestant ideas, Albert began to consider a radical solution.

At Wittenberg in 1522 and at Nuremberg in 1524, Martin Luther encouraged him to convert the order's territory into a secular principality under his personal rule, as the Teutonic Knights would not be able to survive the Protestant Reformation.[5]

Establishment

On April 10, 1525 Albert resigned his position, became a Protestant, and in the Prussian Homage was granted the title "Duke of Prussia" by his uncle, King Sigismund I the Old of Poland. In a deal partly brokered by Luther, Ducal Prussia became the first Protestant state, anticipating the dispensations of the Peace of Augsburg of 1555.

When Albert returned to Königsberg, he publicly declared his conversion and announced to a quorum of Teutonic Knights his new ducal status. The knights who disapproved of the decision were pressured into acceptance by Albert's supporters and the burghers of Königsberg, and only Eric of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, Komtur of Memel, opposed the new duke. On 10 December 1525, at their session in Königsberg, the Prussian estates established the Lutheran Church in Ducal Prussia by deciding the Church Order.[4]

By the end of Albert's rule, the offices of Grand Commander and Marshal of the Order had deliberately been left vacant while the order was left with but 55 knights in Prussia. Some of the knights converted to Lutheranism in order to retain their property and then married into the Prussian nobility, while others returned to the Holy Roman Empire and remained Catholic.[6] These remaining Teutonic Knights, led by the next Grand Master, Walter von Cronberg, continued to unsuccessfully claim Prussia, but retained much of the estates in the Teutonic bailiwicks outside of Prussia.

On 1 March 1526 Albert married Princess Dorothea, daughter of King Frederick I of Denmark, thereby establishing political ties between Lutheranism and Scandinavia. Albert was greatly aided by his elder brother George, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach, who had earlier established the Protestant religion in his territories of Franconia and Upper Silesia. Albert also found himself reliant on support from his Jagiellonian uncle Sigismund I of Catholic Poland, as the Holy Roman Empire and the Roman Catholic Church had banned him for his Protestantism.

The Teutonic Order had only superficially carried out its mission to Christianize the native rural population and had erected few churches within the state's territory.[4] There was little longing for Roman Catholicism. Baltic Old Prussians and Prussian Lithuanian peasants continued to practice pagan customs in some areas, for example adhering to beliefs in Perkūnas (Perkunos), symbolized by the goat buck, Potrimpo, and Pikullos (Patollu) while "consuming the roasted flesh of a goat".[7] Bishop George of Polentz had forbidden the widespread forms of pagan worship in 1524, and repeated the ban in 1540.[4]

Already on 18 January 1524 Bishop George had ordered to only use native languages at baptisms, which improved the access towards the people.[4] There was little active resistance to the new creed, although the fact that the Teutonic Knights had brought Catholicism and Protestantism made the transition easier.[8]

The Church Order of 1525 provided for visitations of the parishioners and pastors, first carried out by Bishop George in 1538.[4] Because Ducal Prussia was ostensibly a Lutheran land, authorities travelled throughout the duchy ensuring that Lutheran teachings were being followed and imposing penalties on pagans and dissidents. The rural population of native descent was only thoroughly Christianised starting with the Reformation in Prussia.[4]

A peasant rebellion broke out in Sambia in 1525. The combination of taxation by the nobility, the furor of the Protestant Reformation, and the abrupt secularization of the Teutonic Order's remaining Prussian lands exacerbated peasant unrest. The relatively well-to-do rebel leaders, including a miller from Kaimen and an innkeeper from Schaaken in Prussia, were supported by sympathizers in Königsberg. The rebels demanded the elimination of newer taxes by the nobility and a return to an older tax of two marks for every Hufe (the Prussian hide measuring approximately forty acres).

They claimed to be rebelling against the harsh nobility, not against Duke Albert, who was away in the Holy Roman Empire, but they would only swear allegiance to him in person. Upon Albert's return from the Empire, he called for a meeting of the peasants in a field, whereupon he surrounded them with loyal troops and had them arrested without incident; the leaders of the rebellion were subsequently executed.[7] Although there were no more large-scale rebellions, Ducal Prussia became known as a land of Protestant dissent and sectarianism.[8]

In 1544 Duke Albert founded the Albertina University in Königsberg, which became the principal educational establishment for Lutheran pastors and theologians of Prussia.[4] In 1560, the university received a royal privilege from King Sigismund II Augustus of Poland. It was granted rights and autonomy same as those enjoyed by the Kraków University, thus it became one of the leading universities in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The usage of the native languages in church services made Duke Albert appoint exiled Protestant Lithuanian pastors as professors (e.g. Stanislovas Rapolionis and Abraomas Kulvietis), making the Albertina also a centre of Lithuanian language and literature.[9]

While the composition of the nobility changed little in the transition from monastic state to duchy, the hold of the nobility over the dependent peasantry increased. Prussia's free peasants, called Kölmer (holders of free estates according to Culm law), held with about a sixth of the arable land, a considerable share as compared with other nations in the feudal era.[10] The peasant rebellion had frightened the nobles, however, causing them to look to Duke Albert for leadership.

Administratively, little changed in the transition from the Teutonic Knights to ducal rule. Although he was formally a vassal of the crown of Poland, Albert retained self-government for Prussia, his own army, the minting of his currency, a provincial assembly (Prussian Diet, Landtag), and had substantial autonomy in foreign affairs.[11]

Lack of heirs

When Albert died in 1568, his teenage son (exact age is unknown) Albert Frederick inherited the duchy. Joachim II Hector, Elector of Brandenburg, who had converted to Lutheranism in 1539, was after the co-enfeoffment (Mitbelehnung) of his line of the Hohenzollern with the Prussian dukedom. So he tried for gaining his brother-in-law Sigismund II Augustus of Poland and finally succeeded, including the then usual expenses.

On 19 July 1569, when Albert Frederick rendered King Sigismund II homage and was in return enfeoffed as Duke of Prussia in Lublin, the King simultaneously enfeoffed Joachim II and his descendants as co-heir. Administration in the duchy declined as Albert Frederick became increasingly feeble-minded, leading Margrave George Frederick of Brandenburg-Ansbach to become Regent of Prussia in 1577.

Following King Sigismund III's Prussian regency contract (1605) with Joachim Frederick of Brandenburg and his Treaty of Warsaw, 1611, with John Sigismund of Brandenburg, confirming the Brandenburgian co-enfeoffment, these two regents guaranteed free practice of Catholic religion in prevailingly Lutheran Prussia. Based on these contracts some Lutheran churches were reconsecrated as Catholic places of worship (e.g. Nicholas Church, Elbing in 1612).

Transition into Brandenburg-Prussia in 1618

As in 1618, Albert Frederick had no surviving male heirs, the co-enfeoffment of 1569, confirmed by the Treaty of Warsaw in 1611, allowed his son-in-law, Elector John Sigismund of the Hohenzollern branch in Brandenburg, to become the duke's legal successor, thereafter ruling Brandenburg and Ducal Prussia in personal union.

In 1618, the Thirty Years' War broke out, and John Sigismund himself died the following year. His son, George William, was successfully invested with the duchy in 1623 by the king of Poland, Sigismund III Vasa, thus the personal union Brandenburg-Prussia was confirmed.[8] Many of the Prussian Junkers were opposed to rule by the House of Hohenzollern of Berlin and appealed to Sigismund III Vasa for redress, or even incorporation of Ducal Prussia into the Polish kingdom, but without success.[12]

Brandenburg, being a fief of the Holy Roman Empire, and Ducal Prussia, being a Polish fief, made a cross-border real union legally impossible. De facto Brandenburg and Ducal Prussia were more and more ruled as one, and colloquially referred to as Brandenburg-Prussia.

Frederick William "Great Elector", duke of Prussia and prince-elector of Brandenburg, wished to acquire Royal Prussia in order to territorially connect his two fiefs. Yet, during the Second Northern War, Charles X Gustav of Sweden invaded Ducal Prussia and dictated the Treaty of Königsberg (January 1656), which made the duchy a Swedish fief. In the subsequent Treaty of Marienburg (June 1656), Charles X Gustav promised to cede to Frederick William the Polish voivodships of Chełmno, Malbork, Pomerania, and the Prince-Bishopric of Warmia, if Frederick William would support Charles Gustav's effort.[13]:82 The proposition was somewhat risky, since Frederick William would definitely have to provide military support, while the reward could only be provided conditional on victory. When the tide of the war turned against Charles X Gustav, he concluded the Treaty of Labiau (November 1656), making Frederick William I the full sovereign in Ducal Prussia and Warmia, which, however, was part of Poland.

In response to the Swedish-Prussian alliance, King John II Casimir of Poland submitted a counter-offer which Frederick William accepted. They signed the Treaty of Bromberg on 6 September 1657 and the Treaty of Wehlau on 29 July 1657. In return for Frederick William's renunciation of the Swedish-Prussian alliance, John Casimir recognised Frederick William's full sovereignty over the Duchy of Prussia.[13]:83 After almost 200 years of Polish suzerainty over the Teutonic Monastic State of Prussia and its successor Ducal Prussia, full sovereignty was regained. Therefore, Duchy of Prussia then became the more adequate appellation for the state. Full sovereignty was a necessary prerequisite to upgrade Ducal Prussia to the sovereign Kingdom of Prussia (not to be confused with Polish Royal Prussia) in 1701.

However, the end of Polish suzerainty was met with reluctance of the population, regardless of ethnicity, as it was afraid of Brandenburg absolutism and wished to remain part of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. The burghers of the capital city of Königsberg, led by Hieronymus Roth, rejected the treaties of Wehlau and Oliva and viewed Prussia as "indisputably contained within the territory of the Polish Crown".[3] It was noted that the incorporation into the Polish Crown under the Treaty of Kraków was approved by the city of Königsberg, while the separation from Poland took place without the city's consent.[3] Polish King John II Casimir Vasa was asked for help, masses were held in Protestant churches for the Polish King and the Polish Kingdom. In 1662, elector Frederick William entered the city with his troops and forced the city to swear allegiance to him, however, in the following decades attempts to return under Polish suzerainty were still made.

Kingdom in 1701

Ducal Prussia's full sovereignty allowed Elector Frederick III of Brandenburg to become "king in Prussia" in 1701 without offending Emperor Leopold I. The government of de facto collectively ruled Brandenburg-Prussia, seated in Brandenburg's capital Berlin, mostly appeared under the higher ranking titles of Prussian government. After the Kingdom of Prussia's annexation of the bulk of the province of Royal Prussia in the First Partition of Poland in 1772, former Ducal Prussia — including previously Polish-controlled Warmia within Royal Prussia — was reorganized into the Province of East Prussia, while most of former Royal Prussia became the Province of West Prussia. The Kingdom of Prussia, then consisting of East and West Prussia, being a sovereign state, and Brandenburg, being a fief within the Holy Roman Empire, were amalgamated de jure only after the latter's dissolution in 1806.

References

- The duchy's Evangelical (Protestant) church was the first formally established as a state religion.

- Notes and Queries, Oxford University Press, 1850

- Janusz Jasiński, Polska a Królewiec, Komunikaty Mazursko-Warmińskie nr 2, 2005, p. 126 (in Polish)

- Albertas Juška, Mažosios Lietuvos Bažnyčia XVI-XX amžiuje, Klaipėda: 1997, pp. 742–771, here after the German translation Die Kirche in Klein Litauen (section: 2. Reformatorische Anfänge; (in German)) on: Lietuvos Evangelikų Liuteronų Bažnyčia, retrieved on 28 August 2011.

- Christiansen, Eric. The Northern Crusades. Penguin Books. London, 1997. ISBN 0-14-026653-4

- Seward, Desmond. The Monks of War: The Military Religious Orders. Penguin Books. London, 1995. ISBN 0-14-019501-7

- Kirby, David. Northern Europe in the Early Modern Period: The Baltic World, 1492–1772. Longman. London, 1990. ISBN 0-582-00410-1

- Koch, H.W. A History of Prussia. Barnes & Noble Books. New York, 1978. ISBN 0-88029-158-3

- Albertas Juška, Mažosios Lietuvos Bažnyčia XVI-XX amžiuje, Klaipėda: 1997, pp. 742–771, here after the German translation Die Kirche in Klein Litauen (section: 5. Die Pfarrer und ihre Ausbildung; (in German)) on: Lietuvos Evangelikų Liuteronų Bažnyčia, retrieved on 28 August 2011.

- Peter Brandt in collaboration with Thomas Hofmann, Preußen: Zur Sozialgeschichte eines Staates; eine Darstellung in Quellen, edited on behalf of Berliner Festspiele as catalogue to the exhibition on Prussia between 15 May and 15 November 1981, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1981, (=Preußen; vol. 3), pp. 24 and 35. ISBN 3-499-34003-8

- Urban, William. The Teutonic Knights: A Military History. Greenhill Books. London, 2003. ISBN 1-85367-535-0

- Eulenberg, Herbert. The Hohenzollerns. Translated by M.M. Bozman. The Century Co. New York, 1929.

- Rutkowski, Henryk (1983). "Rivalität der Magnaten und Bedrohung der Souveränität" [Rivalry of the Magnates and the Threat of Sovereignty]. Polen. Ein geschichtliches Panorama [Poland: A Historical Panorama] (in German). Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Interpress. pp. 81–91. ISBN 83-223-1984-3.