Viking activity in the British Isles

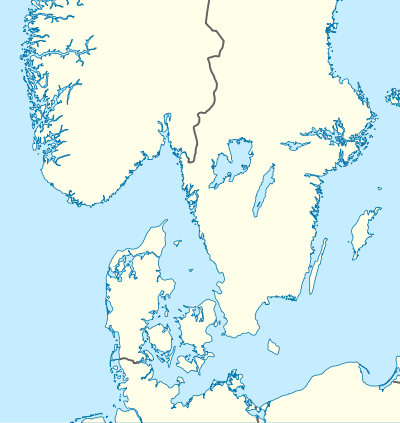

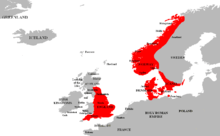

Viking activity in the British Isles occurred during the Early Middle Ages, the 8th to the 10th centuries, when Norsemen from Scandinavia travelled to Great Britain and Ireland to settle, trade or raid. Those who came to the British Isles have been generally referred to as Vikings,[1][2] but some scholars debate whether the term Viking[lower-alpha 1] represented all Norse settlers or just those who raided.[4] [lower-alpha 2]

At the start of the Early Medieval period, Norse kingdoms in Scandinavia had developed trade links reaching as far as southern Europe and the Mediterranean, giving them access to foreign imports such as silver, gold, bronze and spices. These trade links also extended westward into Ireland and Britain.[5][6]

In the last decade of the 8th century, Norse raiders sacked a series of Christian monasteries located in what is now the United Kingdom, beginning in 793 with a raid on the coastal monastery of Lindisfarne on the north-east coast of England. The following year they sacked the nearby Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey, and in 795 they attacked again, raiding Iona Abbey on Scotland's west coast.[7]

Background

During the Early Medieval period, Ireland and Britain were culturally, linguistically and religiously divided into various peoples. The languages of the Celtic Britons and Gaels were descended from the Celtic languages spoken by Iron Age inhabitants of Europe. In Ireland and parts of western Scotland, as well as the Isle of Man, people were speaking an early form of Gaelic known as Old Irish. In Cornwall, Cumbria, Wales, and southwest Scotland, the Celtic Brythonic languages were spoken, with modern descendants such as Welsh and Cornish. In the area north of the Forth and Clyde rivers, which constitutes a large portion of modern-day Scotland, dwelled the Picts who spoke the Pictish language. Due to the scarcity of writing in Pictish, all of which can be found in Ogham, views are conflicted as to whether Pictish was a Celtic language like those spoken further south, or perhaps even a non-Indo-European language like Basque. However, most inscriptions and place names hint towards the Picts being Celtic in language and culture. Most peoples of Britain and Ireland had already predominantly converted to Christianity from their older, pre-Christian polytheistic religions. In contrast to the rest of the isles though, much of southern Britain was considered to be part of Anglo-Saxon England, where Anglo-Saxon migrants from continental Europe had settled during the 5th century CE, bringing with them their own Germanic language (known as Old English), a polytheistic religion (Anglo-Saxon paganism) and their own distinct cultural practices. By the time of the Viking incursions though, Anglo-Saxon England too had become mostly Christian.

The Isle of Man had supported its own agrarian population, but it is widely believed that it was Brythonic-speaking before Old Irish (later to become Manx) spread there. Gaelicisation could have taken place before the Viking age or perhaps during it, when the area was settled by Norse-Gaels who practised their own culture.

In northern Britain, in the area roughly corresponding to modern-day Scotland, lived three distinct ethnic groups in their own respective kingdoms: the Picts, Scots and Britons.[8] The Pictish cultural group dominated the majority of Scotland, with major populations concentrated between the Firth of Forth and the River Dee, as well as in Sutherland, Caithness, and Orkney.[9] The Scots were, according to written sources, a tribal group which had crossed to Britain from Dalriada in the north of Ireland during the late 5th century. Archaeologists have not been able to identify anything that was unique to the kingdom of the Scots, noting similarities with the Picts in most forms of material culture.[10] The Britons were those dwelling in the Old North, in parts of what have become southern Scotland and northern England, and by the 7th or 8th centuries, these had apparently come under the political control of the Anglo-Saxons.[11]

By the mid-9th century, Anglo-Saxon England was divided into four separate and independent kingdoms: East Anglia, Wessex, Northumbria, and Mercia, the last of which was the strongest military power.[12] Between half a million and a million people lived in England at this time, with society being rigidly hierarchical. This class system had a king and his ealdormen at the top, under whom were the thegns, or landholders, and then the various categories of agricultural workers below them. Beneath all of these was a class of slaves, who may have made up as much as a quarter of the population.[12] The majority of the populace lived in the countryside, although a few large towns had developed, namely London and York, which were centres of royal and ecclesiastical administration. There were also a number of trading ports, such as Hamwic and Ipswich, where foreign trade took place.[12]

Scandinavia

Society in 8th century Scandinavia was, unlike parts of the British Isles, still pre-literate, existing in the final stages of European prehistory, known to archaeologists as the Iron Age. In Scandinavia, the 8th century proved to be "a period of rapid technological, economic and social development" which would lead the region out of the Iron Age and into what has come to be known as the Viking Age.[13]

At the start of the Early Medieval period, the Norse populations saw themselves primarily as inhabitants of specific locations, such as Jutland, Vestfold and Hordaland. It would only be in the later centuries that the national identities would develop amongst the Scandinavians, dividing them into such national groups as the Danes, Swedes and Norwegians.[14]

The Late Iron Age peoples of Scandinavia had not yet been converted to Christianity as the peoples of Britain and Ireland had been, and instead followed Norse paganism, a polytheistic set of beliefs that revered such deities as Odin, Thor, Frey and Freyja.[15]

Scandinavian society was heavily dependent on herring fishing, and when that failed, the seafaring Norse sailors turned to navigating around much of Europe during the Early Mediaeval period.[16] The Norse populations of Scandinavia had developed trade links with many areas of Europe, obtaining large quantities of gold in the late 5th century, most of which had been found in Sweden, and to a lesser extent, Norway.[5]

Viking raids: 793–850 AD

In the final decade of the 8th century AD, Norse raiders attacked a series of Christian monasteries in the British Isles. Here, these monasteries had often been positioned on small islands and in other remote coastal areas so that the monks could live in seclusion, devoting themselves to worship without the interference of other elements of society. At the same time, it made them isolated and unprotected targets for attack.[17] Historian Peter Hunter Blair remarked that the Viking raiders would have been astonished "at finding so many communities which housed considerable wealth and whose inhabitants carried no arms."[17] These raids would have been the first contact many Norsemen had with Christianity, but such attacks were not specifically anti-Christian in nature, rather the monasteries were simply seen as 'easy targets' for raiders.[15]

Archbishop Alcuin of York on the sacking of Lindisfarne.[18]

The first known account of a Viking raid in Anglo-Saxon England comes from 789, when three ships from Hordaland (in modern Norway) landed in the Isle of Portland on the southern coast of Wessex. They were approached by Beaduheard, the royal reeve from Dorchester, whose job it was to identify all foreign merchants entering the kingdom, and they proceeded to kill him.[18] It is likely that there were other raids (the records of which have since been lost) soon afterwards, for in 792 King Offa of Mercia began to make arrangements for the defence of Kent from raids perpetrated by "pagan peoples".[18]

The next recorded attack against the Anglo-Saxons came the following year, in 793, when the monastery at Lindisfarne, an island off England's eastern coast, was sacked by a Viking raiding party on 8 June.[18] The following year they sacked the nearby Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey.[7]

In 795 they once again attacked, this time raiding Iona Abbey off Scotland's west coast.[7] This monastery was attacked again in 802 and 806, when 68 people living there were killed. After this devastation, the monastic community at Iona abandoned the site and fled to Kells in Ireland.[19]

In the first decade of the 9th century AD, Viking raiders began to attack coastal districts of Ireland.[20] In 835, the first major Viking raid in southern England took place and was directed against the Isle of Sheppey.[21][22][23]

England Runestones

The England runestones (Swedish: Englandsstenarna) is a group of about 30 runestones in Sweden which refer to Viking Age voyages to England.[24] They constitute one of the largest groups of runestones that mention voyages to other countries, and they are comparable in number only to the approximately 30 Greece Runestones[25] and the 26 Ingvar Runestones, of which the latter refer to a Viking expedition to the Middle East. They were engraved in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark.

The Anglo-Saxon rulers paid large sums, Danegelds, to Vikings, who mostly came from Denmark and Sweden who arrived to the English shores during the 990s and the first decades of the 11th century. Some runestones relate of these Danegelds, such as the Yttergärde runestone, U 344, which tells of Ulf of Borresta who received the danegeld three times, and the last one he received from Canute the Great. Canute sent home most of the Vikings who had helped him conquer England, but he kept a strong bodyguard, the Þingalið, and its members are also mentioned on several runestones.[26]

The vast majority of the runestones, 27, were raised in modern-day Sweden and 17 in the oldest Swedish provinces around lake Mälaren. In contrast, modern-day Denmark has no such runestones, but there is a runestone in Scania which mentions London. There is also a runestone in Norway and a Swedish one in Schleswig, Germany.

Some Vikings, such as Guðvér did not only attack England, but also Saxony, as reported by the Grinda Runestone Sö 166 in Södermanland:[24]

Treasure hoards

Various hoards of treasure were buried in England at this time. Some of these may have been deposited by Anglo-Saxons attempting to hide their wealth from Viking raiders, and others by the Viking raiders as a way of protecting their looted treasure.[18]

One of these hoards, discovered in Croydon (historically part of Surrey, now in Greater London) in 1862, contained 250 coins, three silver ingots and part of a fourth as well as four pieces of hack silver in a linen bag. Archaeologists interpret this as loot collected by a member of the Viking army. By dating the artefacts, archaeologists estimated that this hoard had been buried in 872, when the army wintered in London.[18] The coins themselves came from a wide range of different kingdoms, with Wessex, Mercian and East Anglian examples found alongside foreign imports from Carolingian-dynasty Francia and from the Arab world.[18] Not all such Viking hoards in England contain coins, however: for example, at Bowes Moor, Durham, 19 silver ingots were discovered, whilst at Orton Scar, Cumbria, a silver neck-ring and penannular brooch were uncovered.[28]

The historian Peter Hunter Blair believed that the success of the Viking raids and the "complete unpreparedness of Britain to meet such attacks" became major factors in the subsequent Norse invasions and colonization of large parts of the British Isles.[17]

Invasion and Danelaw: 865–896

From 865 the Norse attitude towards the British Isles changed, as they began to see it as a place for potential colonisation rather than simply a place to raid. As a result of this, larger armies began arriving on Britain's shores, with the intention of conquering land and constructing settlements there.[29]

England

Norse armies captured York, the major city in the Kingdom of Northumbria, in 866.[29] Counterattacks concluded in a decisive defeat for Anglo-Saxon forces at York on 21 March 867, and the deaths of Northumbrian leaders Ælla and Osberht.

Other Anglo-Saxon kings began to capitulate to the Viking demands, and surrendered land to Norse settlers.[30] In addition, many areas in eastern and northern England – including all but the northernmost parts of Northumbria – came under the direct rule of Viking leaders or their puppet kings.

King Æthelred of Wessex, who had been leading the conflict against the Vikings, died in 871 and was succeeded on the throne of Wessex by his younger brother, Alfred.[29] The Viking king of Northumbria, Halfdan Ragnarrson (Old English: Healfdene) – one of the leaders of the Viking Great Army (known to the Anglo-Saxons as the Great Heathen Army) – surrendered his lands to a second wave of Viking invaders in 876. In the next four years, Vikings gained further land in the kingdoms of Mercia and East Anglia as well.[29] King Alfred continued his conflict with the invading forces, but was driven back into Somerset in the south-west of his kingdom in 878, where he was forced to take refuge in the marshes of Athelney.[29]

Alfred regrouped his military forces and defeated the armies of the Norse monarch of East Anglia, Guthrum, at the Battle of Edington (May 878). In 886, the Wessex and the Norse-controlled, East Anglian governments signed the Treaty of Wedmore, which established a boundary between the two kingdoms. The area to the north and east of this boundary became known as the Danelaw because it was under Norse political influence, whilst those areas south and west of it remained under Anglo-Saxon dominance.[29] Alfred's government set about constructing a series of defended towns or burhs, began the construction of a navy, and organised a militia system (the fyrd) whereby half of his peasant army remained on active service at any one time.[29] To maintain the burhs, and the standing army, he set up a taxation and conscription system known as the Burghal Hidage.[31]

In 892, a new Viking army, with 250 ships, established itself in Appledore, Kent[32] and another army of 80 ships soon afterwards in Milton Regis.[32] The army then launched a continuous series of attacks on Wessex. However, due in part to the efforts of Alfred and his army, the kingdom's new defences proved to be a success, and the Viking invaders were met with a determined resistance and made less of an impact than they had hoped. By 896, the invaders dispersed - instead settling in East Anglia and Northumbria, with some instead sailing to Normandy.[29][32]

Alfred's policy of opposing the Viking settlers continued under his daughter Æthelflæd, who married Æthelred, Ealdorman of Mercia, and also under her brother, King Edward the Elder (reigned 899-924). In 920 the Northumbrian government and the Scots government both submitted to the military power of Wessex, and in 937 the Battle of Brunanburh led to the collapse of Norse power in northern Britain.[33]

Edward's son Edmund became king of the English in 939. However, when Edmund was killed in a brawl, his younger brother, Eadred of Wessex took over as king. Then in 947 the Northumbrians rejected Eadred and made the Norwegian Eric Bloodaxe (Eirik Haraldsson) their king. Eadred responded by invading and ravaging Northumbria. When the Saxons headed back south, Eric Bloodaxe's army caught up with some them at Castleford and made 'great slaughter[lower-alpha 3]'. Eadred threatened to destroy Northumbria in revenge, so the Northumbrians turned their back on Eric and acknowledged Eadred as their king. The Northumbrians then had another change of heart and accepted Olaf Sihtricsson as their ruler, only to have Eric Bloodaxe remove him and become king of the Northumbrians again. Then in 954 Eric Bloodaxe was expelled[lower-alpha 4] for the second and final time by Eadred. Bloodaxe was the last Norse king of Northumbria.[35]

Norse settlement in the British Isles

The early Norse settlers in Anglo-Saxon England would have appeared visibly different from the Anglo-Saxon populace, wearing specifically Scandinavian styles of jewellery, and probably also wearing their own peculiar styles of clothing. Norse and Anglo-Saxon men also had different hairstyles: Norsemen's hair was shaved at the back and left shaggy on the front, whilst the Anglo-Saxons typically wore their hair long.[36]

Second invasion: 980–1012

England

Under the reign of Wessex King Edgar the Peaceful, England came to be further politically unified, with Edgar coming to be recognized as the king of all England by both Anglo-Saxon and Norse populations living in the country.[37] However, in the reigns of his son Edward the Martyr, who was murdered in 978, and then Æthelred the Unready, the political strength of the English monarchy waned, and in 980 Viking raiders from Scandinavia resumed attacks against England.[37] The English government decided that the only way of dealing with these attackers was to pay them protection money, and so in 991 they gave them £10,000. This fee did not prove to be enough, and over the next decade the English kingdom was forced to pay the Viking attackers increasingly large sums of money.[37] Many English began to demand that a more hostile approach be taken against the Vikings, and so, on St Brice's Day in 1002, King Æthelred proclaimed that all Danes living in England would be executed. It would come to be known as the St. Brice's Day massacre.[37]

The news of the massacre reached King Sweyn Forkbeard in Denmark. It is believed that Sweyn's sister Gunhilde could have been among the victims, which prompted Sweyn to raid England the following year, when Exeter was burned down. Hampshire, Wiltshire, Wilton and Salisbury also fell victim to the Viking revenge attack.[38][39] Sweyn continued his raid in England and in 1004 his Viking army looted East Anglia, plundered Thetford and sacked Norwich, before he once again returned to Denmark.[40]

Further raids took place in 1006–1007, and in 1009–1012 Thorkell the Tall led a Viking invasion into England.

In 1013 Sweyn Forkbeard returned to invade England with a large army, and Æthelred fled to Normandy, leading Sweyn to take the English throne. Sweyn died within a year however, and so Æthelred returned, but in 1016 another Norse army invaded, this time under the control of the Danish King Cnut, Sweyn's son.[41] After defeating Anglo–Saxon forces at the Battle of Assandun, Cnut became king of England, subsequently ruling over both the Danish and English kingdoms.[41] Following Cnut's death in 1035, the two kingdoms were once more declared independent and remained so apart from a short period from 1040 to 1042 when Cnut's son Harthacnut ascended the English throne.[41]

Written records

Archaeologists James Graham-Campbell and Colleen E. Batey noted that there was a lack of historical sources discussing the earliest Viking encounters with the British Isles, which would have most probably been amongst the northern island groups, those closest to Scandinavia.[42]

The Irish Annals provide us with accounts of much Norse activity during the 9th and 10th centuries.[43]

The Viking raids that affected Anglo-Saxon England were primarily documented in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals initially written in the late 9th century, most probably in the Kingdom of Wessex during the reign of Alfred the Great. The Chronicle is however a biased source, acting as a piece of "wartime propaganda" written on behalf of the Anglo-Saxon forces against their Norse opponents, and in many cases greatly exaggerates the size of the Norse fleets and armies, thereby making any Anglo-Saxon victories against them seem more heroic.[44]

Archaeological evidence

The Norse settlers in the British Isles left remains of their material culture behind, which archaeologists have been able to excavate and interpret during the 20th and 21st centuries. Such Norse evidence in Britain consists primarily of Norse burials undertaken in Shetland, Orkney, the Western Isles, the Isle of Man, Ireland and the north-west of England.[43] Archaeologists James Graham-Campbell and Colleen E. Batey remarked that it was on the Isle of Man where Norse archaeology was "remarkably rich in quality and quantity".[4]

However, as archaeologist Julian D. Richards commented, Scandinavians in Anglo-Saxon England "can be elusive to the archaeologist" because many of their houses and graves are indistinguishable from those of the other populations living in the country.[2] For this reason, historian Peter Hunter Blair noted that in Britain, the archaeological evidence for Norse invasion and settlement was "very slight compared with the corresponding evidence for the Anglo-Saxon invasions" of the 5th century.[43]

See also

- Kingdom of the Isles

- Scandinavian Scotland

- Orkney

- Earldom of Orkney

- History of Shetland

- Orkneyinga saga

- Viking Age

- Category:Scandinavian Scotland

- Norman conquest of England

References

Footnotes

- The word "Viking" is a historical revival; it was not used in Middle English, but it was revived from Old Norse vikingr "freebooter, sea-rover, pirate, Viking", which usually is explained as meaning properly "one who came from the fjords" from vik "creek, inlet, small bay" (cf. Old English wic, Middle High German wich "bay", and the second element in Reykjavik). But Old English wicing and Old Frisian wizing are almost 300 years older, and probably derive from wic "village, camp" (temporary camps were a feature of the Viking raids), related to Latin vicus "village, habitation".[3]

- Graham-Campbell and Batey suggest that "...true Vikings [are] those who took part in Viking raids....A Viking base, is thus a base from which Vikings went raiding, but a Norse settlement in Scotland is a settlement occupied by people of Scandinavian origin..."[4]

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Worcester MSS D for AD 948 says- "And when the king [Eadred] was on his way home, the raiding army [Eric Bloodaxe], which was in York, overtook the king's army at Castleford and a great slaughter was made there."

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says that Bloodaxe was 'driven out' from Northumbria; however other sources claim that he was also killed'[34]

Citations

- Keynes 1999. p. 460.

- Richards 1991. p. 9.

- Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 12 February January 2020Archived 7 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 3.

- Blair 2003. pp. 56–57.

-

Blair, Peter Hunter (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England. Anglo-Saxon studies (revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780521537773. Retrieved 30 Apr 2019.

A variety of evidence, among which some of the objects from Sutton Hoo hold a prominent place, indicates that England lay well within the range of Scandinavia's foreign contacts before the Viking attacks began.

- Blair 2003. p. 55.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 5.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. pp. 5–7.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. pp. 14–16.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 18.

- Richards 1991. p. 13.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 1.

- Richards 1991. p. 11.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 32.

- Richards 1991. p. 12.

- Blair 2003. p. 63.

- Richards 1991. p. 16.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 24.

- Blair 2003. p. 66.

- Blair 2003. p. 68.

- Christopher Wright. Kent through the years. p. 54. ISBN 0-7134-2881-3.

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

- Harrison & Svensson 2007:199

- Jansson 1980:34.

- Harrison & Svensson 2007:198.

- Entry Sö 166 in Rundata 2.0 for Windows.

- Richards 1991. p. 17.

- Richards 1991. p. 20.

- Starkey 2004. p.51

- Horspool 2006. p. 102

- Peter Sawyer. The Oxford Illustrated History of the Vikings. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-19-285434-6.

- Richards 1991 p. 22

- Pearson 2012. p. 131

- Panton 2011. p. 135.

- Richards 1991. pp. 11–12.

- Richards 1991. p. 24.

- "The St Brice's Day Massacre". Historic UK. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Howard 2003, pp. 64–65.

- Howard 2003, pp. 66–67.

- Richards 1991. p. 28.

- Graham-Campbell and Batey 1998. p. 2.

- Blair 2003. p. 64.

- Richards 1991. p. 15.

Bibliography

- Blair, Peter Hunter (2003). An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK and New York City, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53777-3.

- Crawford, Barbara E. (1987). Scandinavian Scotland. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-1282-8.

- DeVries, Kelly (2003). The Norwegian Invasion of England in 1066. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 1-84383-027-2.

- Graham-Campbell, James & Batey, Colleen E. (1998). Vikings in Scotland: An Archaeological Survey. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0641-2.

- Horspool, David (2006). Why Alfred Burned the Cakes. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-86197-786-1.

- Howard, Ian (2003). Swein Forkbeard's Invasions and the Danish Conquest of England, 991-1017 (illustrated ed.). Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851159287.</ref>

- Richards, Julian D. (1991). Viking Age England. London: B. T. Batsford and English Heritage. ISBN 978-0-7134-6520-4.

- Keynes, Simon (1999). Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). "Vikings". The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 460–61.

- Panton, Kenneth J. (2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Plymouth: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5779-7.

- Pearson, William (2012). Erik Bloodaxe: His Life and Times: A Royal Viking in His Historical and Geographical Settings. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4685-8330-4.

- Starkey, David (2004). The Monarchy of England. I. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-7678-4.