Tommaso dei Cavalieri

Tommaso dei Cavalieri (1509–1587) was an Italian nobleman, who was the object of the greatest expression of Michelangelo's love. Cavalieri was 23 years old when Michelangelo met him in 1532, at the age of 57. The young nobleman was exceptionally handsome, and his appearance seems to have fit the artist's notions of ideal masculine beauty, for Michelangelo described him as "light of our century, paragon of all the world."[1] The two men remained lifelong lovers, and Cavalieri was present at the artist's death.[2]

Tommaso dei Cavalieri | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1509 |

| Died | 1587 |

| Known for | Being the object of the greatest expression of Michelangelo's love. |

| Spouse(s) | Lavinia della Valle |

| Children | Emilio de' Cavalieri Mario de' Cavalieri |

Biography

Tommaso dei Cavalieri was the son of Mario de’Cavalieri and Cassandra Bonaventura. Cavalieri was born between 1512 and 1519, but the exact date of his birth is unknown. Cavalieri paid for the mass in the memory of his brother Emilio on 6th September 1536, which is mentioned in an official document, translated by Gerda Panofsky-Soergel. This is the only document that mentions Tommaso age, stating "he is older than 16, but younger than 25". Warren Kirkendale in his book "Emilio de' Cavalieri "Gentiluomo Romano"", corrects Panofsky-Soergel’s reading of the document as stating that Cavalieri was ‘no more than 16’, meaning he was ‘but a boy of twelve’ when he met Michelangelo. Cavalieri’s parents married in November 1509, and had one son, Emilio, before Tommaso was born. After the deaths of his father in 1524, and his older brother, Emilio, in 1536, Tommaso officially became the head of Cavalieri household. His first position in Roman government was caporione of his neighborhood of Sant’Eustachio, which he took in 1539. it was noted that Cavalieri did not participate in civic government extensively, compared to his peers, although Cavalieri would serve in this position five times (in 1539, 1542, 1546, 1558, and 1562). Twice he occupied the post of Conservatore, the highest-ranking office a Roman citizen could occupy (in 1564 and 1571). [3]

Tommaso married Lavinia della Valle in 1544 in Rome. [4] Lavinia was born sometime between 1527 and 1530. She was a daughter of Lorenzo Stefano della Valle and Giulia Caffarelli, and a cousin of Cardinal Andrea della Valle. [5] The marriage of Tommaso and Lavinia was a continuation of longstanding tradition of marriagies between Cavalieri and della Valle families, who had been related by marriage at least since the fifteenth century. The connection of the families was shown when Tommaso dei Cavalieri had sought shelter in Cardinal Andrea della Valle’s palace, where Lavinia’s mother also found refuge, accompanied by three of her children, most likely Lavinia’s older sisters, Orinzia, Polimnia, and Porzia during Sack of Rome in 1527. [6]

Tommaso Cavalieri’s marriage produced two sons, Mario, probably born in 1548, and Emilio, born by 1552, who would go on to become a renowned composer. The marriage lasted nine years, ending with Lavinia della Valle’s death in early November 1553. Lavinia was buried in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, where both the Cavalieri and della Valle families had chapels.

Cavalieri was made one of Convervatori in 1554 and took the position responsible for supervising construction at the Campidoglio, which Michelangelo had begun restorating in 1538. Work on this complex project, involving the renovation of the existing Palazzo dei Conservatori and Palazzo Senatorio, as well as construction of a third building, the Palazzo Nuovo did not begin until 1542 and would not be fully realized until 1662. Cavalieri was co-director for construction from 1554 to 1575 and supervised the project through its most productive phase of development. Despite him sharing responsibility for the construction with Prospero Boccapaduli, Cavalieri is mentioned to have been primarily responsible for the realization of Michelangelo’s designs, while Boccapaduli managed the financial and administrative tasks.

Relationship with Michelangelo

Michelangelo Buonarroti met the young Tommaso dei Cavalieri during a stay in Rome in 1532. Michelangelo was 57 years old at the time and Tommaso three times his younger. There is no certain image of Tommaso survived, but the contemporaries mentioned he was good looking and cultivated. Benedetto Varchi wrote that Cavalieri was of incomparable beauty with graceful manners, so excellent en endowment and so charming a demeanor that he indeed deserved, and still deserves, the more to be loved the better he is known. Michelangelo became infatuated with the young Roman patrician. Vasari noted that Infinitely more than any other friend, Michelangelo loved the young Tommaso, who became the object of Michelangelo’s passion, his muse and the inspiration for letters, numerous poems, and works of visual art. The pair would remain devoted to each other until Michelangelo's death in 1564. The earliest survived letter from Tommaso to Michelangelo is dated by 1 January 1533. The letter gives clues to their budding relationship through a conversation about art. According to Cavalieri, they are united by a mutual love for art. Tommaso’s letter refers to Those works of mine that you have seen with your own eyes, and which have caused you to show me no small affection’.[7]

Poems

Michelangelo dedicated approximately 30 of his total 300 poems to Cavalieri, which made them the artist's largest sequence of poems. Most were sonnets, although there were also madrigals and quatrains. The central theme of all of them was the artist's love for the young nobleman.[8] Some modern commentators assert that the relationship was merely a Platonic affection, even suggesting that Michelangelo was seeking a surrogate son.[9] However, their homoerotic nature was recognized in his own time, so that a decorous veil was drawn across them by his grand-nephew, Michelangelo the Younger, who published an edition of the poetry in 1623 with the gender of pronouns changed. John Addington Symonds, the early British homosexual activist, undid this change by translating the original sonnets into English and writing a two-volume biography, published in 1893.

The sonnets are the first large sequence of poems in any modern tongue addressed by one man to another, predating Shakespeare's sonnets to his young friend by a good fifty years.

Examples include the sonnet G.260. Michelangelo re-iterates his neo-Platonic love for Cavalieri when in the first line of the sonnet he states "Love is not always a harsh and deadly sin."

In the sonnet G.41 Michelangelo states that Tommaso is all that can be. He represents pity, love and piety. This is seen in the third stanza:

|

|

One of the most famous of Michelangelo's poems is G.94, which is also called the "Silkworm." In the sonnet he wants to be garments to clothe the body of Cavalieri.

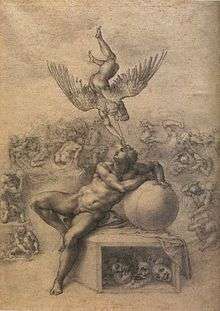

Drawings

Michelangelo also sent Cavalieri four highly finished drawings,[11] termed by Johannes Wilde presentation drawings.[12] These were a new kind of drawing, completed works meant as presents, rather than sketches or studies. They, too, were greatly appreciated by Cavalieri, who was very sorry to lend some of them to members of the papal curia.[11][13] Giorgio Vasari stood on their great originality. The meaning of the drawings is not fully understood, although it is common for scholars to relate them to moralizing themes or ideas about Neoplatonic love.

Punishment of Tityus 1532 and Rape of Ganymede 1532

These two drawings both represent a muscular male attacked by an eagle. Tityus was the son of a human princess and the god Zeus. He attempted to rape a goddess and was killed by two of the gods, but his punishment did not end with death; for eternity he was chained to a rock in Hades while two vultures ate his liver, which was considered the seat of the passions.[14] Zeus lusted after Ganymede, the most beautiful of all humans, and turned himself into an eagle to abduct (or rape) him to serve the god at Mount Olympus. The original drawing is lost and is known today only from copies.

The Fall of Phaeton 1533

Phaeton was the son of Apollo and nagged his father into letting him drive the chariot of the sun. He lost control of the fiery horses and Zeus had to destroy the chariot (and kill Phaeton) with a thunderbolt to keep it from destroying the earth. In Michelangelo's drawing Zeus is riding an eagle as he casts the thunderbolt that overturns the chariot. The women below are Phaeton's grieving sisters. Three versions of this drawing by Michelangelo survive; this is perhaps the final version that was given to Cavalieri by September 6, 1533, the date of a letter to the artist telling him the drawing had been much admired by illustrious visitors (including the Pope and Cardinal Ippolito de' Medici).[15] On another version of the composition, today in the British Museum, Michelangelo wrote a note to Cavalieri: "Master Tommaso, if this sketch does not please you, tell Urbino so that I have time to do another by tomorrow evening, as I promised you. And if you like it and want me to finish it, send it back to me."[16]

Bacchanal of Children 1533

No written source for this drawing is known; presumably, it was an allegory that would have been familiar to Cavalieri. Frederick Hartt investigated the drawing and stated: " Until a specific text is found, there would seem to be little point in speculation, beyond noting that the drawing radiates the irresponsible wildness of certain of Michelangelo's poems. It is perfectly possible that he did not mean us to penetrate its riddles any further."

The Dream 1533

This drawing is not directly linked to Cavalieri, but its resemblance to those drawings has suggested to some scholars that it was related to them. Unlike some of the other drawings, the iconography does not derive from Greek mythology, and its uncertain subject is interpreted as linked with beauty.[11]

References

- Howard Hibbard, Michelangelo, New York, 1974, 229.

- "p. 5" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-18. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- Ruvoldt, Maria (2019). "Gossip and reputation in sixteenth-century Rome: Tommaso de'Cavalieri and Lavinia della Valle". Renaissance Studies. n/a (n/a). doi:10.1111/rest.12611. ISSN 1477-4658.

- Gianni Venditti, Luca Becchetti (2008). Un blasonario secentesco della piccola e media aristocrazia romana. Gangemi Editore.

- Venditti, Gianni (2009). Archivio della Valle-del Bufalo: Inventario. Vatican: Archivio Segreto Vaticano.

- Buonaparte, Jacques (1830). ac de Rome écrit en 1527. Florence: Imprimerie Granducale.

- Gayford, Martin (2013). Michelangelo: His Epic Life. London: Penguin UK. ISBN 978-1905490547.

- Chris Ryan, The Poetry of Michelangelo: An Introduction, Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd., 97–99.

- "Michelangelo", The New Encyclopædia Britannica, Macropaedia, Volume 24, page 58, 1991. The text goes so far as to claim, 'These have naturally been interpreted as indications that Michelangelo was a homosexual, but such a reaction according to the artist's own statement would be that of the ignorant'.

- Buonarroti, Michaelangelo (1904). Sonnets. now for the first time translated into rhymed English. Trans. John Addington Symonds. p. 26.

- "Michelangelo's Dream". The Courtauld Gallery. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- "Presentation Drawing". The Concise Grove Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. 2002. Retrieved 2011-04-10.

- "Casa Buonarroti – Drawings of Michelangelo". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- Howard Hibbard, Michelangelo, New York, 1974, 235.

- Michelangelo. "The Fall of Phaethon". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912766.

- Anthony Hughes, Michelangelo, London, 1997, 233.

Further reading

- John Addington Symonds, The life of Michelangelo Buonarroti, based on studies in the archives of the Buonarroti family at Florence, volume 2, chapter XII (New York: Scribner, 1893).