David (Michelangelo)

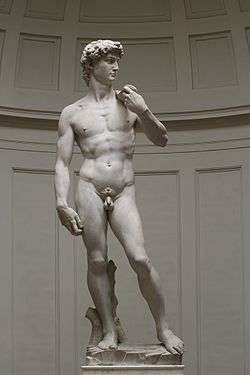

David is a masterpiece of Renaissance sculpture created in marble between 1501 and 1504 by the Italian artist Michelangelo. David is a 5.17-metre (17.0 ft)[lower-alpha 1] marble statue of the Biblical figure David, a favoured subject in the art of Florence.[1]

| David | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Michelangelo |

| Year | 1501–1504 |

| Medium | Marble sculpture |

| Subject | Biblical David |

| Dimensions | 517 cm × 199 cm (17 ft × 6.5 ft) |

| Location | Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, Italy |

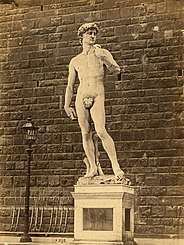

David was originally commissioned as one of a series of statues of prophets to be positioned along the roofline of the east end of Florence Cathedral, but was instead placed in a public square, outside the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of civic government in Florence, in the Piazza della Signoria, where it was unveiled on 8 September 1504. The statue was moved to the Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence, in 1873, and later replaced at the original location by a replica.

Because of the nature of the figure it represented, the statue soon came to symbolize the defence of civil liberties embodied in the Republic of Florence, an independent city-state threatened on all sides by more powerful rival states and by the hegemony of the Medici family. The eyes of David, with a warning glare, were fixated towards Rome.[2]

History

Commission

The history of the statue begins before Michelangelo's work on it from 1501 to 1504.[3] Prior to Michelangelo's involvement, the Overseers of the Office of Works of Florence Cathedral, consisting mostly of members of the influential woolen cloth guild, the Arte della Lana, had plans to commission a series of twelve large Old Testament sculptures for the buttresses of the cathedral.[4] In 1410, Donatello made the first of the statues, a figure of Joshua in terracotta. A figure of Hercules, also in terracotta, was commissioned from the Florentine sculptor Agostino di Duccio in 1463 and was made perhaps under Donatello's direction.[5] Eager to continue their project, in 1464, the Operai contracted Agostino[6] to create a sculpture of David.

A block of marble was provided from a quarry in Carrara, a town in the Apuan Alps in northern Tuscany. Agostino only got as far as beginning to shape the legs, feet and the torso, roughing out some drapery and probably gouging a hole between the legs. His association with the project ceased, for reasons unknown, with the death of Donatello in 1466, and ten years later Antonio Rossellino was commissioned to take up where Agostino had left off. Rossellino's contract was terminated soon thereafter, and the block of marble remained neglected for 26 years, all the while exposed to the elements in the yard of the cathedral workshop. This was of great concern to the Opera authorities, as such a large piece of marble was not only costly, but represented a large amount of labour and difficulty in its transportation to Florence.

In 1500, an inventory of the cathedral workshops described the piece as "a certain figure of marble called David, badly blocked out and supine."[7] A year later, documents showed that the Operai were determined to find an artist who could take this large piece of marble and turn it into a finished work of art. They ordered the block of stone, which they called 'the Giant',[8] "raised on its feet" so that a master experienced in this kind of work might examine it and express an opinion. Though Leonardo da Vinci and others were consulted, it was Michelangelo, at 26 years of age, who convinced the Operai that he deserved the commission.[9] On 16 August 1501, Michelangelo was given the official contract to undertake this challenging new task.[6] He began carving the statue early in the morning on 13 September, a month after he was awarded the contract. He would work on the massive statue for more than two years.

Placement

On 25 January 1504, when the sculpture was nearing completion, Florentine authorities had to acknowledge there would be little possibility of raising the more than six-ton statue to the roof of the cathedral.[10] They convened a committee of 30 Florentine citizens that comprised many artists, including Leonardo da Vinci and Sandro Botticelli, to decide on an appropriate site for David.[11] While nine different locations for the statue were discussed, the majority of members seem to have been closely split between two sites.

One group, led by Giuliano da Sangallo and supported by Leonardo and Piero di Cosimo, among others, believed that, due to the imperfections in the marble, the sculpture should be placed under the roof of the Loggia dei Lanzi on Piazza della Signoria; the other group thought it should stand at the entrance to the Palazzo della Signoria, the city's town hall (now known as Palazzo Vecchio). Another opinion, supported by Botticelli, was that the sculpture should be situated on or near the cathedral.

In June 1504, David was installed next to the entrance to the Palazzo Vecchio, replacing Donatello's bronze sculpture of Judith and Holofernes, which embodied a comparable theme of heroic resistance. It took four days to move the statue the half mile from Michelangelo's workshop into the Piazza della Signoria. Later that summer the sling and tree-stump support were gilded, and the figure was given a gilded loin-garland.[12][13]

Later history

In the mid 1800s, small cracks were noticed on the left leg on David which can possibly be attributed to an uneven sinking of the ground under the massive statue.[14]

In 1873, the statue of David was removed from the piazza, to protect it from damage, and displayed in the Accademia Gallery, Florence, where it attracted many visitors. A replica was placed in the Piazza della Signoria in 1910.[15]

In 1991 Piero Cannata, an artist who the police described as deranged, attacked the statue with a hammer he had concealed beneath his jacket. He later said that a 16th-century Venetian painter's model ordered him to do so.[16] Cannata was restrained as he was in the process of damaging the toes of the left foot.[17]

On 12 November 2010, a fiberglass replica[18] of David was installed on the roofline of Florence Cathedral, for one day only. Photographs of the installation reveal the statue the way the Operai who commissioned the work originally expected it to be seen.

In 2010, a dispute over the ownership of David arose when, based on a legal review of historical documents, the municipality of Florence claimed ownership of the statue in opposition to the Italian Culture Ministry, which disputes the municipality claim.[19][20]

Interpretation

The pose of Michelangelo's David is unlike that of earlier Renaissance depictions of David. The bronze statues by Donatello and Verrocchio represented the hero standing victorious over the head of Goliath, and the painter Andrea del Castagno had shown the boy in mid-swing, even as Goliath's head rested between his feet,[21] but no earlier Florentine artist had omitted the giant altogether. According to Helen Gardner and other scholars, David is depicted before his battle with Goliath.[22][23] Instead of being shown victorious over a foe much larger than he, David looks tense and ready for battle after he has made the decision to fight Goliath but before the battle has actually taken place. His brow is drawn, his neck tense, and the veins bulge out of his lowered right hand. His left hand holds a sling that is draped over his shoulder and down to his right hand, which holds the handle of the sling.[24]

However, John Vedder Edwards, in his "Michelangelo / Revelations" suggests that the David is in fact shown after the defeat of Goliath, and that David is looking in consternation at the Philistine army, concerned as to whether or not they will honor the agreement to settle the dispute on the terms of single-combat previously agreed to.

The twist of his body effectively conveys to the viewer the feeling that he is in motion, an impression heightened with contrapposto. The statue is a Renaissance interpretation of a common ancient Greek theme of the standing heroic male nude. In the High Renaissance, contrapposto poses were thought of as a distinctive feature of antique sculpture. This is typified in David, as the figure stands with one leg holding its full weight and the other leg forward. This classic pose causes the figure's hips and shoulders to rest at opposing angles, giving a slight s-curve to the entire torso. The contrapposto is emphasized by the turn of the head to the left, and by the contrasting positions of the arms.

Michelangelo's David has become one of the most recognized works of Renaissance sculpture, a symbol of strength and youthful beauty. The colossal size of the statue alone impressed Michelangelo's contemporaries. Vasari described it as "certainly a miracle that of Michelangelo, to restore to life one who was dead," and then listed all of the largest and most grand of the ancient statues that he had ever seen, concluding that Michelangelo's work surpassed "all ancient and modern statues, whether Greek or Latin, that have ever existed."[25]

The proportions of the David are atypical of Michelangelo's work; the figure has an unusually large head and hands (particularly apparent in the right hand). The small size of the genitals, though, is in line with his other works and with Renaissance conventions in general, perhaps referencing the ancient Greek ideal of pre-pubescent male nudity. These enlargements may be due to the fact that the statue was originally intended to be placed on the cathedral roofline, where the important parts of the sculpture may have been accentuated in order to be visible from below. The statue is unusually slender (front to back) in comparison to its height, which may be a result of the work done on the block before Michelangelo began carving it.

It is possible that the David was conceived as a political statue before Michelangelo began to work on it.[26] Certainly David the giant-killer had long been seen as a political figure in Florence, and images of the Biblical hero already carried political implications there.[27] Donatello's bronze David, made for the Medici family, perhaps c. 1440, had been appropriated by the Signoria in 1494, when the Medici were exiled from Florence, and the statue was installed in the courtyard of the Palazzo della Signoria, where it stood for the Republican government of the city. By placing Michelangelo's statue in the same general location, the Florentine authorities ensured that David would be seen as a political parallel as well as an artistic response to that earlier work. These political overtones led to the statue being attacked twice in its early days. Protesters pelted it with stones the year it debuted, and, in 1527, an anti-Medici riot resulted in its left arm being broken into three pieces.

Commentators have noted the presence of foreskin on David's penis, which is at odds with the Judaic practice of circumcision, but is consistent with the conventions of Renaissance art.[28][29]

Conservation

During World War II, David was entombed in brick to protect it from damage from airborne bombs.

In 1991, the foot of the statue was damaged by a man with a hammer.[16] The samples obtained from that incident allowed scientists to determine that the marble used was obtained from the Fantiscritti quarries in Miseglia, the central of three small valleys in Carrara. The marble in question contains many microscopic holes that cause it to deteriorate faster than other marbles. Because of the marble's degradation, from 2003 to 2004 the statue was given its first major cleaning since 1843. Some experts opposed the use of water to clean the statue, fearing further deterioration. Under the direction of Franca Falleti, senior restorers Monica Eichmann and Cinzia Parnigoni undertook the job of restoring the statue.[30]

In 2008, plans were proposed to insulate the statue from the vibration of tourists' footsteps at Florence's Galleria dell'Accademia, to prevent damage to the marble.[31]

Replicas

.svg.png)

1. Statue of Unity 240 m (790 ft) (incl. 58 m (190 ft) base)

2. Spring Temple Buddha 153 m (502 ft) (incl. 25 m (82 ft) pedestal and 20 m (66 ft) throne)

3. Statue of Liberty 93 m (305 ft) (incl. 47 m (154 ft) pedestal)

4. The Motherland Calls 87 m (285 ft) (incl. 2 m (6 ft 7 in) pedestal)

5. Christ the Redeemer 38 m (125 ft) (incl. 8 m (26 ft) pedestal)

6. Michelangelo's David 5.17 m (17.0 ft) (excl. 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) plinth)

David has stood on display at Florence's Galleria dell'Accademia since 1873. In addition to the full-sized replica occupying the spot of the original in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, a bronze version overlooks Florence from the Piazzale Michelangelo. The plaster cast of David at the Victoria and Albert Museum has a detachable plaster fig leaf which is displayed nearby. Legend claims that the fig leaf was created in response to Queen Victoria's shock upon first viewing the statue's nudity, and was hung on the figure prior to royal visits, using two strategically placed hooks.[32]

David has often been reproduced,[33] in plaster and imitation marble fibreglass, signifying an attempt to lend an atmosphere of culture even in some unlikely settings such as beach resorts, gambling casinos and model railroads.[34]

See also

- List of works by Michelangelo

- List of statues by height

References

- Notes

- The height of the David was recorded incorrectly and the mistake proliferated through many art history publications. The accurate height was only determined in 1998–99 when a team from Stanford University went to Florence to try out a project on digitally imaging large 3D objects by photographing sculptures by Michelangelo and found that the sculpture was taller than any of the sources had indicated. See and .

- Citations

- See, for example, Donatello's 2 versions of David; Verrocchio's bronze David; Domenico Ghirlandaio's painting of David; and Bartolomeo Bellano's bronze David.

- This theory was first proposed by Saul Levine "The Location of Michelangelo's David: The Meeting of January 25, 1504, The Art Bulletin 56 (1974): 31–49.

- The genesis of David was discussed in Seymour 1967 and in Coonin 2014.

- Charles Seymour, Jr. "Homo Magnus et Albus: the Quattrocento Background for Michelangelo's David of 1501–04," Stil und Überlieferung in der Kunst des Abendlandes, Berlin, 1967, II, 96–105.

- Seymour, 100–101.

- Gaetano Milanesi, Le lettere di Michelangelo Buonarroti pubblicati coi ricordi ed i contratti artistici, Florence, 1875, 620–623: "...the Consuls of the Arte della Lana and the Lords Overseers being met Overseers, have chosen as sculptor to the said Cathedral the worthy master, Michelangelo, the son of Lodovico Buonarrotti, a citizen of Florence, to the end that he may make, finish and bring to perfection the male figure known as the Giant, nine braccia in height, already blocked out in marble by Maestro Agostino grande, of Florence, and badly blocked; and now stored in the workshops of the Cathedral. The work shall be completed within the period and term of two years next ensuing, beginning from the first day of September next ensuing, with a salary and payment together in joint assembly within the hall of the said of six broad florins of gold in gold for every month. And for all other works that shall be required about the said building (edificium) the said Overseers bind themselves to supply and provide both men and scaffolding from their office and all else that may be necessary. When the said work and the said male figure of marble shall be finished, then the Consuls and Overseers who shall at that time be in authority shall judge whether it merits a higher reward, being guided therein by the dictates of their own consciences."

- Giovanni Gaye, Carteggio inedito d'artisti del sec. XIV, XV, XVI, Florence: 1839–40, 2: 454 and Charles Seymour, Michelangelo's David: A Search for Identity, Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh University Press, 1967, 134–137, doc. 34.

- De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 651. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- Coughlan, Robert (1966). The World of Michelangelo: 1475–1564. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 85.

- The statue has not been weighed, but an estimate of its weight was circulated in 2004, when the statue was cleaned. See a CBS news report of 8 March 2004.

- The minutes of the meeting were published in Giovanni Gaye, Carteggio inedito d'artisti del sec. XIV, XV, XVI, Florence, 1839–40, 2: 454–463. For an English translation of the document, see Seymour, Michelangelo's David, 140–155 and for an analysis, see Saul Levine, "The Location of Michelangelo's David: The Meeting of January 25, 1504, Art Bulletin 56 (1974): 31–49; N. Randolph Parks, "The Placement of Michelangelo's David: A Review of the Documents," Art Bulletin, 57 (1975) 560–570; and Rona Goffen, Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian, New Haven, 2002, 123–127.

- Goffen (2002), p. 130.

- Coonin, 2014, pp. 90–94.

- A., Borri (2006). "Diagnostic analysis of the lesions and stability of Michelangelo's David". Journal of Cultural Heritage. 7 (4): 273–285. doi:10.1016/j.culher.2006.06.004 – via ScienceDirect.

- Coonin, 2014.

- "a man the police described as deranged, broke part of a toe with a hammer, saying a 16th century Venetian painter's model ordered him to do so." Cowell, Alan. "Michelangelo's David Is Damaged", New York Times, 1991-09-15. Retrieved on 2008-05-23.

- Rossella Lorenzi, Art lovers go nuts over dishy David, ABC Science, Monday, 21 November 2005

- "Michelangelo's David as It Was Meant to Be Seen : Discovery News". news.discovery.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2016. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Povoledo, Elisabetta (31 August 2010). "Who Owns Michelangelo's 'David'?". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- Pisa, Nick (16 August 2010). "Florence vs Italy: Michelangelo's David at centre of ownership row". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- "File:Andrea del castagno, scudo di david con la testa di golia, 1450-55 circa, 02.JPG – Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Helen Gardner, Fred S. Kleiner, Christin J. MamiyaIt, Gardner's Art Through the Ages retrieved February 17, 2009

- Howard Hibbard, Michelangelo, New York: Harper & Row, 1974, 59–61; Anthony Hughes, Michelangelo, London: Phaidon, 1997, 74.

- "David Sculpture, Michelango's David, Michelangelo Gallery".

- Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori nelle redazioni del 1550 e 1568, ed. Rosanna Bettarini and Paola Barocchi, Florence, 1966–87, 6: 21.

- Levine, 45–46.

- Butterfield, Andrew (1995). "New Evidence for the Iconography of David in Quattrocento Florence". I Tatti Studies. 8: 115–133.

- Strauss, RM; Marzo-Ortega, H (2002). "Michelangelo and medicine". J R Soc Med. 95 (10): 514–5. doi:10.1258/jrsm.95.10.514. PMC 1279184. PMID 12356979.

- Coonin, 2014, pp. 105-108.

- Eric Scigliano. "Inglorious Restorations. Destroying Old Masterpieces in Order to Save Them." Harper's Magazine. August 2005, 61–68.

- "Michelangelo's David 'may crack'". BBC News. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "David's Fig Leaf". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 29 May 2007.

- " You need not travel to Florence to see Michelangelo's David. You can see it well enough for educational purposes in reproduction," asserted E. B. Feldman in 1973 (Feldman, "The teacher as model critic", Journal of Aesthetic Education, 1973).

- That "typical examples of kitsch include fridge magnets showing Michelangelo’s David." is reported even in the British Medical Journal (J Launer, "Medical kitsch", BMJ, 2000)

Bibliography

| |

- Coonin, A. Victor, From Marble to Flesh: The Biography of Michelangelo’s David, Florence: The Florentine Press, 2014. ISBN 9788897696025.

- Goffen, Rona (2002). Renaissance Rivals: Michelangelo, Leonardo, Raphael, Titian. Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hall, James, Michelangelo and the Reinvention of the Human Body New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

- Hartt, Frederick, Michelangelo: the complete sculpture, New York: Abrams Books,1982.

- Hibbard, Howard. Michelangelo, New York: Harper & Row, 1974.

- Hirst Michael, “Michelangelo In Florence: David In 1503 and Hercules In 1506,” The Burlington Magazine, 142 (2000): 487–492.

- Hughes, Anthony, Michelangelo, London: Phaidon Press, 1997.

- Levine, Saul, "The Location of Michelangelo's David: The Meeting of January 25, 1504", The Art Bulletin, 56 (1974): 31–49.

- Natali, Antonio; Michelangelo (2014). Michelangelo Inside and Outside the Uffizi. Florence: Maschietto. ISBN 978-88-6394-085-5.

- Pope-Hennessy, John, Italian High Renaissance and Baroque Sculpture. London: Phaidon, 1996.

- Seymour, Charles, Jr. Michelangelo's David: a search for identity (Mellon Studies in the Humanities), Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1967.

- Vasari, Giorgio, The Lives of the Artists (Penguin Books), “Life of Michelangelo”, pp. 325–442.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Michelangelo's David. |

- 10 Facts That You Don't Know About Michelangelo's David,

- Michelangelo Buonarroti: David, Art and the Bible

- The Digital Michelangelo Project, Stanford University

- Models of wax and clay used by Michelangelo in making his sculpture and paintings

- The Museums of Florence – The David of Michelangelo

- "Michelangelo's David". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved 18 March 2013.