The Jungle

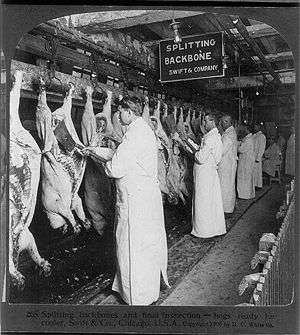

The Jungle is a 1906 novel by the American journalist and novelist Upton Sinclair (1878–1968).[1] Sinclair wrote the novel to portray the harsh conditions and exploited lives of immigrants in the United States in Chicago and similar industrialized cities. His primary purpose in describing the meat industry and its working conditions was to advance socialism in the United States.[2] However, most readers were more concerned with several passages exposing health violations and unsanitary practices in the American meat packing industry during the early 20th century, which greatly contributed to a public outcry which led to reforms including the Meat Inspection Act. Sinclair famously said of the public reaction, "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach."

_cover.jpg) First edition | |

| Author | Upton Sinclair |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Political fiction |

| Publisher | Doubleday, Page & Co. |

Publication date | February 26, 1906 |

| Media type | Print (hardcover) |

| Pages | 413 |

| OCLC | 149214 |

The book depicts working-class poverty, the lack of social supports, harsh and unpleasant living and working conditions, and a hopelessness among many workers. These elements are contrasted with the deeply rooted corruption of people in power. A review by the writer Jack London called it "the Uncle Tom's Cabin of wage slavery."[3]

Sinclair was considered a muckraker, or journalist who exposed corruption in government and business.[4] In 1904, Sinclair had spent seven weeks gathering information while working incognito in the meatpacking plants of the Chicago stockyards for the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason. He first published the novel in serial form in 1905 in the newspaper, and it was published as a book by Doubleday in 1906.

Plot summary

The main character in the book, Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant, tries to make ends meet in Chicago. The book begins with his wife Ona and his wedding feast. He and his family live near the stockyards and meatpacking district where many immigrants, who do not know much English, work. He takes a job at Brown's slaughterhouse. Jurgis had thought the US would offer more freedom, but he finds working-conditions harsh. He and his young wife struggle to survive as they fall deeply into debt and become prey to con men. Hoping to buy a house, they exhaust their savings on the down payment for a substandard slum house, which they cannot afford. The family is eventually evicted after their money is taken.

Jurgis had expected to support his wife and other relatives, but eventually all—the women, children, and his sick father—seek work to survive. As the novel progresses, the jobs and means the family use to stay alive slowly lead to their physical and moral decay. Accidents at work and other events lead the family closer to catastrophe. Jurgis' father dies as a direct result of the unsafe work-conditions in the meatpacking plant. One of the children, Kristoforas, dies from food poisoning. Jonas—the other remaining adult male aside from Jurgis—disappears and is never heard from again. Then an injury results in Jurgis being fired from the meatpacking plant; he later takes a job at Durham's fertilizer plant. The family's breakdown progresses as Jurgis discovers an arrangement in which Ona has traded regular sexual favors to Phil Connor, Jurgis' boss, in exchange for being allowed to keep her job. In revenge, Jurgis attacks Connor, resulting in his arrest and imprisonment.

After being released from jail, Jurgis finds that his family has been evicted from their house. He finds them staying in a boarding house, where Ona is in labor with her second child. She dies in childbirth at age 18 from blood loss; the infant also dies - Jurgis had lacked the money for a doctor. Soon after, his first child drowns in a muddy street. Jurgis leaves the city and takes up drinking. His brief sojourn as a hobo in the rural United States shows him that no real escape is available—farmers turn their workers away when the harvest is finished.

Jurgis returns to Chicago, holds down a succession of laboring jobs and works as a con man. He drifts without direction. He finds out that Marija, Ona's cousin, had become a prostitute to support the family and is now addicted to morphine; Stanislovas, the oldest of the children at the beginning of the novel, had died after getting locked in at work and being eaten alive by rats. One night Jurgis wanders into a lecture being given by a socialist orator, where he finds community and purpose. After a fellow socialist employs him, Jurgis locates his wife's family and resumes his financial support of them. The book ends with another socialist rally, which follows some political victories.

Characters

.tiff.png)

- Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian who immigrates to the US and struggles to support his family.

- Ona Lukoszaite Rudkus, Jurgis' teenage wife.

- Marija Berczynskas, Ona's cousin. She dreams of marrying a musician. After Ona's death and Rudkus' abandonment of the family, she becomes a prostitute to help feed the few surviving children.

- Teta Elzbieta Lukoszaite, Ona's stepmother. She takes care of the children and eventually becomes a beggar.

- Grandmother Swan, another Lithuanian immigrant.

- Dede Antanas, Jurgis' father. He contributes work despite his age and poor health; dies from a lung infection.

- Jokubas Szedvilas, Lithuanian immigrant who owns a deli on Halsted Street.

- Edward Marcinkus, Lithuanian immigrant and friend of the family.

- Fisher, Chicago millionaire whose passion is helping poor people in slums.

- Tamoszius Kuszleika, a fiddler who becomes Marija's fiancé.

- Jonas Lukoszas, Teta Elzbieta's brother. He abandons the family in bad times and disappears.

- Stanislovas Lukoszas, Elzibeta's eldest son; he starts work at 14, with false documents that say he is 16.

- Mike Scully (originally Tom Cassidy), the Democratic Party "boss" of the stockyards.

- Phil Connor, a boss at the factory where Ona works. Connor rapes Ona and forces her into prostitution.

- Miss Henderson, Ona's forelady at the wrapping-room.

- Antanas, son of Jurgis and Ona, otherwise known as "Baby".

- Vilimas and Nikalojus, Elzbieta's second and third sons.

- Kristoforas, a crippled son of Elzbieta.

- Juozapas, another crippled son of Elzbieta.

- Kotrina, Elzbieta's daughter and Ona's half sister.

- Judge Pat Callahan, a crooked judge.

- Jack Duane, a thief whom Rudkus meets in prison.

- Madame Haupt, a midwife hired to help Ona.

- Freddie Jones, son of a wealthy beef baron.

- Buck Halloran, an Irish "political worker" who oversees vote-buying operations.

- Bush Harper, a man who works for Mike Scully as a union spy.

- Ostrinski, a Polish immigrant and socialist.

- Tommy Hinds, the socialist owner of Hinds's Hotel.

- Mr. Lucas, a socialist pastor and itinerant preacher.

- Nicholas Schliemann, a Swedish philosopher and socialist.

- Durham, a businessman and Jurgis's second employer.

Publication history

Sinclair published the book in serial form between February 25, 1905, and November 4, 1905, in Appeal to Reason, the socialist newspaper that had supported Sinclair's undercover investigation the previous year. This investigation had inspired Sinclair to write the novel, but his efforts to publish the series as a book met with resistance. An employee at Macmillan wrote,

I advise without hesitation and unreservedly against the publication of this book which is gloom and horror unrelieved. One feels that what is at the bottom of his fierceness is not nearly so much desire to help the poor as hatred of the rich.[5]

Five publishers rejected the work as it was too shocking.[6] Sinclair was about to self-publish a shortened version of the novel in a "Sustainer's Edition" for subscribers when Doubleday, Page came on board; on February 28, 1906 the Doubleday edition was published simultaneously with Sinclair's of 5,000 which appeared under the imprint of “The Jungle Publishing Company” with the Socialist Party’s symbol embossed on the cover, both using the same plates.[7] In the first 6 weeks, the book sold 25,000 copies.[8] It has been in print ever since, including four more self-published editions (1920, 1935, 1942, 1945).[7] Sinclair dedicated the book "To the Workingmen of America".[9]

The copyright (in some countries) expired after 100 years, so there is now (as of March 11, 2006) a free or "public domain" copy of the book available on the web site of Project Gutenberg.[10]

Uncensored edition

In 2003, See Sharp Press published an edition based on the original serialization of The Jungle in Appeal to Reason, which they described as the "Uncensored Original Edition" as Sinclair intended it. The foreword and introduction say that the commercial editions were censored to make their political message acceptable to capitalist publishers.[11] Others argue that Sinclair had made the revisions himself to make the novel more accurate and engaging for the reader, corrected the Lithuanian references, and streamlined to eliminate boring parts, as Sinclair himself said in letters and his memoir American Outpost (1932).[7]

Reception

Upton Sinclair intended to expose "the inferno of exploitation [of the typical American factory worker at the turn of the 20th Century]",[12] but the reading public fixed on food safety as the novel's most pressing issue. Sinclair admitted his celebrity arose "not because the public cared anything about the workers, but simply because the public did not want to eat tubercular beef".[12]

Sinclair's account of workers falling into rendering tanks and being ground along with animal parts into "Durham's Pure Leaf Lard" gripped the public. The poor working conditions, and exploitation of children and women along with men, were taken to expose the corruption in meat packing factories.

The British politician Winston Churchill praised the book in a review.[13]

In 1933, the book became a target of the Nazi book burnings due to Sinclair's endorsement of socialism.[14]

Federal response

President Theodore Roosevelt had described Sinclair as a "crackpot" because of the writer's socialist positions.[15] He wrote privately to journalist William Allen White, expressing doubts about the accuracy of Sinclair's claims: "I have an utter contempt for him. He is hysterical, unbalanced, and untruthful. Three-fourths of the things he said were absolute falsehoods. For some of the remainder there was only a basis of truth."[16] After reading The Jungle, Roosevelt agreed with some of Sinclair's conclusions. The president wrote "radical action must be taken to do away with the efforts of arrogant and selfish greed on the part of the capitalist."[17] He assigned the Labor Commissioner Charles P. Neill and social worker James Bronson Reynolds to go to Chicago to investigate some meat packing facilities.

Learning about the visit, owners had their workers thoroughly clean the factories prior to the inspection, but Neill and Reynolds were still revolted by the conditions. Their oral report to Roosevelt supported much of what Sinclair portrayed in the novel, excepting the claim of workers falling into rendering vats.[18] Neill testified before Congress that the men had reported only "such things as showed the necessity for legislation."[19] That year, the Bureau of Animal Industry issued a report rejecting Sinclair's most severe allegations, characterizing them as "intentionally misleading and false", "willful and deliberate misrepresentations of fact", and "utter absurdity".[20]

Roosevelt did not release the Neill–Reynolds Report for publication. His administration submitted it directly to Congress on June 4, 1906.[21] Public pressure led to the passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act; the latter established the Bureau of Chemistry (in 1930 renamed as the Food and Drug Administration).

Sinclair rejected the legislation, which he considered an unjustified boon to large meat packers. The government (and taxpayers) would bear the costs of inspection, estimated at $30,000,000 annually.[22][23] He complained about the public's misunderstanding of the point of his book in Cosmopolitan Magazine in October 1906 by saying, "I aimed at the public's heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach."[24]

Adaptations

A film version of the novel was made in 1914, but it has since been lost.[25] Sinclair reportedly bought the negative of the film prior to 1916, hoping to market the film nationally after its initial release in 1914.

Footnotes

- Brinkley, Alan (2010). "17: Industrial Supremacy". The Unfinished Nation. McGrawHill. ISBN 978-0-07-338552-5.

- Van Wienen, Mark W. (2012). "American socialist triptych: the literary-political work of Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Upton Sinclair, and W.E.B. Du Bois. n.p.". Book Review Digest Plus (H.W. Wilson). University of Michigan Press.

- "Upton Sinclair", Social History (biography), archived from the original (blog) on 2012-05-27.

- Sinclair, Upton, "Note", 'The Jungle, Dover Thrift, pp. viii–x

- Upton Sinclair, Spartacus Educational.

- Gottesman, Ronald. "Introduction". The Jungle. Penguin Classics.

- Phelps, Christopher. "The Fictitious Suppression of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle". History News Network. George Mason University. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- "The Jungle and the Progressive Era | The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. 2012-08-28. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- Bloom, Harold, ed. (2002), Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, Infohouse, pp. 50–51, ISBN 1604138874.

- Sinclair, Upton. "The Jungle". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- Sinclair, Upton (1905). The Jungle: The Uncensored Original Edition. Tucson, AZ: See Sharp Press. p. vi. ISBN 1884365302.

- Sullivan, Mark (1996). Our Times. New York: Scribner. p. 222. ISBN 0-684-81573-7.

- Arthur, Anthony (2006), Radical Innocent: Upton Sinclair, New York: Random House, pp. 84–85.

- "Banned and/or Challenged Books from the Radcliffe Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of the 20th Century". American Library Association. March 26, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- Oursler, Fulton (1964), Behold This Dreamer!, Boston: Little, Brown, p. 417.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1951–54) [July 31, 1906], Morison, Elting E (ed.), The Letters, 5, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, p. 340.

- "Sinclair, Upton (1878–1968)". Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

- Jacobs, Jane, "Introduction", The Jungle, ISBN 0-8129-7623-1.

- Hearings Before the Committee on Agriculture... on the So-called "Beveridge Amendment" to the Agricultural Appropriation Bill, U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Agriculture, 1906, p. 102, 59th Congress, 1st Session.

- Hearings Before the Committee on Agriculture... on the So-called "Beveridge Amendment" to the Agricultural Appropriation Bill, U.S. Congress, House, Committee on Agriculture, 1906, pp. 346–50, 59th Congress, 1st Session.

- Roosevelt, Theodore (1906), Conditions in Chicago Stockyards (PDF)

- Young, The Pig That Fell into the Privy, p. 477.

- Sinclair, Upton (1906), "The Condemned-Meat Industry: A Reply to Mr. M. Cohn Armour", Everybody's Magazine, XIV, pp. 612–13.

- Bloom, Harold. editor, Upton Sinclair's The Jungle, Infobase Publishing, 2002, p. 11

- "The Jungle". silentera.com.

Further reading

- Bachelder, Chris (January–February 2006). "The Jungle at 100: Why the reputation of Upton Sinclair's good book has gone bad". Mother Jones Magazine.

- Lee, Earl. "Defense of The Jungle: The Uncensored Original Edition". See Sharp Press.

- Øverland, Orm (Fall 2004). "The Jungle: From Lithuanian Peasant to American Socialist". American Literary Realism. 37 (1): 1–24.

- Phelps, Christopher. "The Fictitious Suppression of Upton Sinclair's The Jungle". hnn.us.

- Young, James Harvey (1985). "The Pig That Fell into the Privy: Upton Sinclair's The Jungle and Meat Inspection Amendments of 1906". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 59 (1): 467–480.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: The Jungle (novel) |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- The Jungle, available at Internet Archive (scanned books first edition)

- The Jungle at Project Gutenberg (plain text and HTML)

- The Jungle at the Standard Ebooks site.

- The Jungle serialized in The Sun newspaper from the Florida Digital Newspaper Library

- PBS special report marking the 100th anniversary of the novel

- Northwestern University's Medill School of Journalism revisits The Jungle