The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird

The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird is a Sicilian fairy tale collected by Giuseppe Pitrè,[1] and translated by Thomas Frederick Crane for his Italian Popular Tales.[2] Joseph Jacobs included a reconstruction of the story in his European Folk and Fairy Tales.[3] The original title is "Li Figghi di lu Cavuliciddaru", for which Crane gives a literal translation of "The Herb-gatherer's Daughters."[4]

| The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird | |

|---|---|

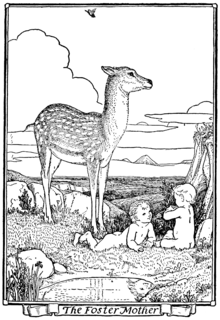

The foster mother (doe) looks after the wonder-children. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird |

| Data | |

| Aarne-Thompson grouping | ATU 707 (The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird; The Bird of Truth, or The Three Golden Children, or The Three Golden Sons) |

| Region | Eurasia, Worldwide |

| Related | Ancilotto, King of Provino; Princess Belle-Étoile and Prince Chéri; The Tale of Tsar Saltan; The Boys with the Golden Stars |

The story is the prototypical example of Aarne–Thompson–Uther tale-type 707, to which it gives its name.[5] Alternate names for the tale type are The Three Golden Sons, The Three Golden Children, The Bird of Truth, Portuguese: Os meninos com uma estrelinha na testa, lit. 'The boys with little stars on their foreheads',[6] Russian: Чудесные дети, romanized: Chudesnyye deti, lit. 'The Wonderful or Miraculous Children',[7] or Hungarian: Az aranyhajú ikrek, lit. 'The Golden-Haired Twins'.[8]

According to folklorist Stith Thompson, the tale is "one of the eight or ten best known plots in the world".[9]

Synopsis

Note: the following is a summary of the tale as it was collected by Giuseppe Pitrè and translated by Thomas Frederick Crane.

A king walking the streets heard three poor sisters talk. The oldest said that if she married the royal butler, she would give the entire court a drink out of one glass, with water left over. The second said that if she married the keeper of the royal wardrobe, she would dress the entire court in one piece of cloth, and have some left over. The youngest said that if she married the king, she would bear two sons with apples in their hands, and a daughter with a star on her forehead.

The next morning, the king ordered the older two sisters to do as they said, and then married them to the butler and the keeper of the royal wardrobe, and the youngest to himself. The queen became pregnant, and the king had to go to war, leaving behind news that he was to hear of the birth of his children. The queen gave birth to the children she had promised, but her sisters, jealous, put three puppies in their place, sent word to the king, and handed over the children to be abandoned. The king ordered that his wife be put in a treadwheel crane.

Three fairies saw the abandoned children and gave them a deer to nurse them, a purse full of money, and a ring that changed color when misfortune befell one of them. When they were grown, they left for the city and took a house.

Their aunts saw them and were terror-struck. They sent their nurse to visit the daughter and tell her that the house needed the Dancing Water to be perfect and her brothers should get it for her. The oldest son left and found three hermits in turn. The first two could not help him, but the third told him how to retrieve the Dancing Water, and he brought it back to the house. On seeing it, the aunts sent their nurse to tell the girl that the house needed the Singing Apple as well, but the brother got it, as he had the Dancing Water. The third time, they sent him after the Speaking Bird, but as one of the conditions was that he not respond to the bird, and it told him that his aunts were trying to kill him and his mother was in the treadmill, it shocked him into speech, and he was turned to stone. The ring changed colors. His brother came after him, but suffered the same fate. Their sister came after them both, said nothing, and transformed her brother and many other statues back to life.

They returned home, and the king saw them and thought that if he did not know his wife had given birth to three puppies, he would think these his children. They invited him to dinner, and the Speaking Bird told the king all that had happened. The king executed the aunts and their nurse and took his wife and children back to the palace.

Overview

The following summary was based on Joseph Jacobs's tale reconstruction in his Europa's Fairy Book, on the general analyses made by Arthur Bernard Cook in his Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion,[10] and on the description of the tale-type in the Aarne–Thompson–Uther Index classification of folk and fairy tales.[11] This type follows an almost fixed structure, with very similar characteristics, regardless of their geographic distribution:[10]

The king passes by a house or other place where three sisters are gossiping or talking, and the youngest says, if the king married her, she would bear him "wondrous children" (their peculiar appearances tend to vary, but they are usually connected with astronomical motifs on some part of their bodies, such as the Sun, the moon or stars). The king overhears their talk and marries the youngest sister, to the envy of the older ones or to the chagrin of the grandmother. As such, the jealous relatives deprive the mother of her newborn children (in some tales, twins or triplets, or three consecutive births, but the boy is usually the firstborn, and the girl is the youngest), either by replacing the children with animals or accusing the mother of having devoured them. Their mother is banished from the kingdom or severely punished (imprisoned in the dungeon or in a cage; walled in; buried up to the torso). Meanwhile, the children are either hidden by a servant of the castle (gardener, cook, butcher) or cast into the water, but they are found and brought up at a distance from the father's home by a childless foster family (fisherman, miller, etc.).

Years later, after they reach a certain age, a magical helper (a fairy, or the Virgin Mary in more religious variants) gives them means to survive in the world. Soon enough, the children move next to the palace where the king lives, and either the aunts, or grandmother realize their nephews/grandchildren are alive and send the midwife (or a maid; a witch; a slave) or disguise themselves to tell the sister that her house needs some marvellous items, and incite the girl to convince her brother(s) to embark on the (perilous) quest. The items also tend to vary, but in many versions there are three treasures: (1) water, or some water source (e.g., spring, fountain, sea, stream) with fantastic properties (e.g., a golden fountain, or a rejuvenating liquid); (2) a magical tree (or branch, or bough, or flower, or a fruit - usually apples) with strange powers (e.g., makes music or sings); and (3) a wondrous bird that can tell the truth, knows many languages and/or turns people to stone.[12]

The brother(s) set(s) off on his (their) journey, but give(s) a token to the sister so she knows the brother(s) is(are) alive. Eventually, the brothers meet a character (a sage, an ogre, etc.) that warns them not to listen to the bird, otherwise he will be petrified (or turned to salt, or to marble pillars). The first brother fails the quest, and so does the next one. The sister, seeing that the tokens changed colour, realizes her siblings are in danger and departs to finish the quest for the wonderful items and rescue her brother(s).

Afterwards, either the siblings invite the king or the king invites the brothers and their sister for a feast in the palace. As per the bird's instructions, the siblings display their etiquette during the meal (in some versions, they make a suggestion to invite the disgraced queen; in others, they give their poisoned meal to some dogs). Then, the bird reveals the whole truth, the children are reunited with their parents, and the jealous relatives are punished.

Variations

While the formula is almost followed to the letter, some variations occur in the second part of the story (the quest for the magical items), and even in the conclusion of the tale:

The Brother Quests for a Bride

In some tales, when the sister is lured by the antagonist's agent, she is told to look for the belongings (mirror, flower, handkerchief) of a woman of unearthly beauty or a fairy. Such variants occur in Albania, as in the tales collected by J. G. Von Hahn in his Griechische und Albanische Märchen (Leipzig, 1864), in the village of Zagori in Epirus,[13] and by Auguste Dozon in Contes Albanais (Paris, 1881). These stories substitute the quest for the items for the search for a fairy named E Bukura e Dheut ("Beauty of the Land"), a woman of extraordinary beauty and magical powers.[14][15] One such tale is present in Robert Elsie's collection of Albanian folktales (Albania's Folktales and Legends): The Youth and the Maiden with Stars on their Foreheads and Crescents on their Breasts.[16][17]

Another version of the story is The Tale of Arab-Zandyq,[18][19] in which the brother is the hero who gathers the wonderful objects (a magical flower and a mirror) and their owner (Arab-Zandyq), whom he later marries. Arab-Zandyq replaces the bird and, as such, tells the whole truth during her wedding banquet.[20][21]

In a specific Armenian variant, called The Twins, the last quest for the brother is to find the daughter of an Indian king and bring her to his king's palace. In this version, it is a king who overhears the sisters' nightly conversation in his search for a wife for his son. At the end, the brother marries the foreign princess and his sister reveals the truth to the court.[22]

This conclusion also happens in an Indian variant, called The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead, from Bengali. In this tale, the seventh queen begets the wonder-children (fraternal twins, a girl and a boy); the antagonists are the other six queens, who, overcome with jealousy, trick the new queen with puppies and expose the children. When they both grow up, the jealous queens set the siblings on a quest for a kataki flower, with the brother rescuing Lady Pushpavati from Rakshasas. Lady Pushpavati marries the titular "boy with the moon on his forehead" and reveals to the King her mother-in-law's ordeal and the deceit of the King's co-wives.[23]

In an extended version from a Breton source, called L'Oiseau de Vérité,[24] the youngest triplet, a king's son, listens to the helper (an old woman), who reveals herself to be a princess enchanted by her godmother. In a surprise appearance by said godmother, she prophecises her goddaughter shall marry the hero of the tale (the youngest prince), after a war with another country.

The Sister marries a Prince

In an Icelandic variant collected by Ján Árnuson and translated in his book Icelandic Legends (1866), with the name Bóndadæturnar (The Story of the Farmer's Three Daughters, or its German translation, Die Bauerntöchter),[25] the quest focus on the search for the bird and omits the other two items. The end is very much the same, with the nameless sister rescuing her brothers Vilhjámr and Sigurdr and a prince from the petrification spell and later marrying him.[26]

Another variant where this happy ending occurs is Princesse Belle-Étoile et Prince Chéri, by Mme. D'Aulnoy, where the heroine rescues her cousin, Prince Chéri, and marries him. Another French variant, collected by Henry Carnoy (L'Arbre qui chante, l'Oiseau qui parle et l'Eau d'or, or "The tree that sings, the bird that speaks and the water of gold"), has the youngest daughter, the princess, marry an enchanted old man she meets in her journey and who gives her advice on how to obtain the items.[27]

In a tale collected in Carinthia (Kärnten), Austria (Die schwarzen und die weißen Steine, or "The black and white stones"), the three siblings climb a mountain or slope, but the brothers listen to the sounds of the mountain and are petrified. Their sister arrives at a field of white and black stones and, after a bird gives her instructions, sprinkles magic water on the stones, restoring her brothers and many others - among them, a young man, whom she later marries.[28]

In the Armenian variant Théodore, le Danseur, the brother ventures on a quest for the belongings of the eponymous character and, at the conclusion of the tale, this fabled male dancer marries the sister.[29][30]

In The Three Little Birds, a folktale collected by the Brothers Grimm, in Kinder- und Hausmärchen (KHM nr. 96), instructed by an old woman fishing, the sister strikes a black dog and it transforms into a prince, with whom she marries as the truth settles among the family.

A similar conclusion happens in the commedia dell'arte The Green Bird, where the brother undergoes the quest for the items, and the titular green bird is a cursed prince, who, after being released from its avian form, marries the sister.

The Tale of Tsar Saltan

Some versions of the tale have the mother being cast out with the babies into the sea in a box, after the king is tricked into thinking his wife did not deliver her promised wonder children. The box eventually washes ashore on the beaches of an island or another country. There, the child (or children) magically grows up in hours or days and builds an enchanted castle or house that attracts the attention of the common folk (or merchants, or travellers). Word reaches the ears of the despondent king, who hears about the mysterious owners of such fantastic abode, who just happen to look like the children he would have had.

Russian tale collections attest to the presence of Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore, as the antagonist in many of the stories.[31]

In some variants, the castaway boy sets a trap to rescue his brothers and release them from a transformation curse. For example, in Nád Péter ("Schilf-Peter"), a Hungarian variant,[32] when the hero of the tale sees a flock of eleven swans flying, he recognizes them as their brothers, who have been transformed into birds due to divine intervention by Christ and St. Peter.

In another format, the boy asks his mother to prepare a meal with her "breast milk" and prepares to invade his brothers' residence to confirm if they are indeed his siblings. This plot happens in a Finnish variant, from Ingermanland, collected in Finnische und Estnische Volksmärchen (Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne, or "Brother and Sister, and the golden-haired sons of the King").[33] The mother gives birth to six sons with special traits who are sold to a devil by the old midwife. Some time later, their youngest brother enters the devil's residence and succeeds in rescuing his siblings.

The Boys With The Golden Stars

The motif of a woman's babies, born with wonderful attributes after she claimed she could bear such children, but stolen from her, is a common fairy tale motif. In this plot-type, an evil stepmother (or grandmother, or gypsy, or slave, or maid) kills the babies, but the twins go through a resurrective reincarnation: from trees to animals and finally into humans babies again. This transformation chase where the stepmother is unable to prevent the children's reappearance is unusual, although it appears in "A String of Pearls Twined with Golden Flowers" and in "The Count's Evil Mother", a Croatian tale from the Karlovac area.[34]

Most versions of The Boys With Golden Stars[35] begin with the birth of male twins, but very rarely there are fraternal twins, a boy and a girl. When they transform into human babies again, the siblings grow up at an impossibly fast rate and hide their supernatural trait under a hood or a cap. Soon after, they show up in their father's court or house to reveal the truth through a riddle or through a ballad.

This tale's format happens in many variants collected in the Balkan area, specially in Romenia,[36][37] as it can be seen in The Boys with the Golden Stars (Romanian: Doi feți cu stea în frunte) collected in Rumänische Märchen,[38] which Andrew Lang included in his The Violet Fairy Book.[39]

Alternate Source for the Truth to the King (Father)

In a Kaba'il version from Northern Algeria (Les enfants et la chauve-souris),[40] the bird is replaced by a bat, who helps the abandoned children when their father takes them back and his second wife prepares them a poisoned meal. The bat recommends the siblings to give their meal to animals, in order to prove it's poisoned and to reveal the treachery of the second wife.[41]

In a specific folktale from Egypt, El-Schater Mouhammed,[42] the Brother is the hero of the story, but the last item of the quest (the bird) is replaced by "a baby or infant who can speak eloquently", as an impossible MacGuffin. The fairy (or mystical woman) he sought before gives both siblings instructions to summon the being in front of the king, during a banquet.

In many widespread variants, the bird is replaced by a fairy or magical woman the Brother seeks after as part of the impossible tasks set by his aunts, and whom he later marries (The Brother Quests for a Bride format). Very rarely, it is one of the children themselves that reveal the aunts' treachery to their father, as seen in the Armenian variants The Twins and Theodore, le Danseur.[29][30] In a specific Persian version, from Kamani, the Prince (King's son) investigates the mystery of the twins and questions the midwife who helped in the delivery of his children.[43]

Motifs

The Persecuted Wife and the Wonder Children

The story of the birth of the wonderful children can be found in Medieval author Johannes de Alta Silva's Dolopathos sive de Rege et Septem Sapientibus (c. 1190), a Latin version of the Seven Sages of Rome.[44] The tale was adapted into the French Li romans de Dolopathos by the poet Herbert.[45] Dolopathos also comprises the Knight of the Swan cycle of stories. This version of the tale preserves the motif of the wonder-children, which are born "with golden chains around their necks", the substitution for animals and the degradation of the mother, but merges with the fairy tale The Six Swans, where brothers transformed into birds are rescued by the efforts of their sister,[46] which is Aarne-Thompson 451, "The boys or brothers transformed into birds".

In a brief summary:[44][47] a lord encounters a mysterious woman (clearly a swan maiden or fairy) in the act of bathing, while clutching a gold necklace, they marry and she gives birth to a septuplet, six boys and a girl, with golden chains about their necks. But her evil mother-in-law swaps the newborn with seven puppies. The servant with orders to kill the children in the forest just abandons them under a tree. The young lord is told by his wicked mother that his bride gave birth to a litter of pups, and he punishes her by burying her up to the neck for seven years. Some time later, the young lord while hunting encounters the children in the forest, and the wicked mother's lie starts to unravel. The servant is sent out to search them, and find the boys bathing in the form of swans, with their sister guarding their gold chains. The servant steals the boys' chains, preventing them from changing back to human form, and the chains are taken to a goldsmith to be melted down to make a goblet. The swan-boys land in the young lord's pond, and their sister, who can still transform back and forth into human shape by the magic of her chain, goes to the castle to obtain bread to her brothers. Eventually the young lord asks her story so the truth comes out. The goldsmith was actually unable to melt down the chains, and had kept them for himself. These are now restored back to the six boys, and they regain their powers, except one, whose chain the smith had damaged in the attempt. So he alone is stuck in swan form. The work goes on to say obliquely hints that this is the swan in the Swan Knight tale, more precisely, that this was the swan “quod cathena aurea militem in navicula trahat armatum (that tugged by a gold chain an armed knight in a boat).”[44]

The motif of the heroine persecuted by the queen, on false pretenses, also happens in Istoria della Regina Stella e Mattabruna,[48] a rhyming story of the ATU 706 type (The Maiden Without Hands).[49]

India-born author Maive Stokes suggested that the motif of the children's "silver chains" (in her notes) are parallel to the astronomical motifs on the children's bodies.[50]

Waldemar Liungman has suggested that this tale has an even earlier point of origin, with a possible source in Hellenistic times.[51]

It has been suggested by Russian scholars that the first part of the tale (the promises of the three sisters and the substitution of babies for animals/objects) may found parallels in stories of the indigenous populations of the Americas.[52]

Astronomical Signs on Bodies

The motif of the children born with astronomical signs on their bodies appears in Russian fairy tales and healing incantations,[7] with the formula "a red star or sun in the front, a moon on the back of the neck and a body covered with stars". However, Western scholars interpret the motif as a sign of royalty.[53]

India-born author Maive Stokes, as commented by Joseph Jacobs, noted that the motif of children born with stars, moon or a sun in some part of their bodies occurred to heroes and heroines of both Asian and European fairy tales,[54] and are by no means restricted to the ATU 707 tale type.

The Dancing Water

Scholars have proposed that the quest for the Dancing Water in these tales are part of a macrocosm of similar tales about the quest for a Water of Life or Fountain of Immortality.[55]

The reincarnation motif in The Boys with The Golden Stars format

It has been suggested that the transformation sequence in the tale format (from human babies, to trees, to lambs/goats and finally to humans again) may be underlying a theme of reincarnation, metempsychosis or related to a life-death-rebirth cycle.[56] This motif is shared by other tale types, and does not belong exclusively to the ATU 707.

India-born author Maive Stokes noted the resurrective motif of the murdered children, and found parallels among European tales published during that time.[57]

Distribution

According to Joseph Jacobs's Europa's Fairy Book, the tale format is widespread[41][58] throughout Europe[59] and Asia (Middle East and India).[60] Portuguese writer, playwright and literary critic Teófilo Braga, in his Contos Tradicionaes do Povo Portuguez, confirms the wide area of presence of the tale, specially in Italy, France, Germany, Spain and in Russian and Slavic sources.[61]

The tale can also be found across Brazil, Syria, "White Russia, The Caucasus, Egypt, Arabia".[62]

Earliest literary sources

The first attestation of the tale is possibly Ancilotto, King of Provino, an Italian literary fairy tale written by Giovanni Francesco Straparola in The Facetious Nights of Straparola (1550-1555).[63][64] A fellow Italian scholar, bishop Pompeo Sarnelli (anagrammatised into nom de plume Marsillo Reppone), wrote down his own version of the story, in Posilecheata (1684), preserving the Neapolitan accent in the books' pages: La 'ngannatora 'ngannata, or L'ingannatora ingannata ("The deceiver deceived").[65][66][67]

Spanish scholars suggest that the tale can be found in Iberia's literary tradition of the late 15th and early 16th centuries: Lope de Vega's commedia La corona de Hungría y la injusta venganza contains similarities with the structure of the tale, suggesting that the Spanish playwright may have been inspired by the story,[68] since the tale is present in Spanish oral tradition. In the same vein, Menéndez Y Pelayo writes in his literary treatise Orígenes de la Novela that an early version exists in Contos e Histórias de Proveito & Exemplo, published in Lisbon in 1575,[69] but this version lacks the fantastical motifs.[70][71]

Two ancient French literary versions exist: Princesse Belle-Étoile et Prince Chéri, by Mme. D'Aulnoy (of Contes de Fées fame), in 1698,[72] and L'Oiseau de Vérité ("The Bird of Truth"), penned by French author Eustache Le Noble, in his collection La Gage touché (1700).[73][74]

Europe

Italy

Italy seems to concentrate a great number of variants, from Sicily to the Alps.[62] Italian folklorist of Sicilian origin, Giuseppe Pitrè collected at least five variants in his book Fiabe Novelle e Racconti Popolari Siciliani, Vol. 1 (1875).[75] Pitrè also comments on the presence of the tale in Italian scholarly literature of his time. His work continued in the supplement publication of Curiosità popolari tradizionali, which recorded a variant from Ciociaria (Le tre figli);[76] and a variant from Sardinia (Is tres sorris; English: "The three sisters").[77]

An Italian variant named El canto e 'l sono della Sara Sybilla ("The Sing-Song of Sybilla Sara"), replaces the magical items for an indescribable MacGuffin, obtained from a supernatural old woman. The strange object also reveals the whole plot at the end of the tale.[78] Vittorio Imbriani, who collected the previous version, also gathers three more in the same book La Novellaja Fiorentina: L'Uccellino, che parla; L'Uccel Bel-Verde and I figlioli della campagnola.[79] Gherardo Nerucci, a fellow Italian scholar, has recorded El canto e 'l sono della Sara Sybilla and I figlioli della campagnola, in his Sessanta novelle popolari montalesi: circondario di Pistoia[80] The story of "Sara Sybilla" has been translated to English as The Sound and Song of the Lovely Sibyl, with a source in Tuscany, but differing from the original in that it reinserts the bird as the truth-teller to the King.[81]

Vittorio Imbriani also compiles a Milanese version (La regina in del desert), which he acknowledges as a sister story to that of Sarnelli's and Straparola's.[82]

Fellow folklorist Laura Gonzenbach, from Switzerland, translated a Sicilian variant into the German language: Die verstossene Königin und ihre beiden ausgesetzten Kinder (The banished queen and her two children).[83]

Domenico Comparetti collected a variant named Le tre sorelle ("The Three Sisters"), from Monferrato[84] and L'Uccellino che parla ("The speaking bird"), a version from Pisa[85] - both in Novelline popolari italiane.

Gennaro Finamore collected a version from Abruzzo, in Italy, named Lu fatte de le tré ssurèlle, with references to Gonzenbach, Pitrè, Comparetti and Imbriani.[86]

In a fable from Mantua (La fanciulla coraggiosa, or "The brave girl"), the story of the siblings's mother and aunts and the climax at the banquet are skipped altogether. The tale is restricted to a quest for the water-tree-bird in order to embellish their garden.[87]

Angelo de Gubernatis lists two variants from Santo Stefano di Calcinaia: I cagnolini and Il Re di Napoli,[88] and an unpublished, nameless version collected in Tuscany, near the source of the Tiber river.[89][90]

The "Istituto centrale per i beni sonori ed audiovisivi" ("Central Institute of Sound and Audiovisual Heritage") promoted research and registration throughout the Italian territory between the years 1968-1969 and 1972. In 1975 the Institute published a catalog edited by Alberto Maria Cirese and Liliana Serafini including 55 variants of the ATU 707 type.[91]

The tale seems to have inspired Carlo Gozzi's commedia dell'arte work L'Augellino Belverde ("The Green Bird").[92][93] In it, the eponymous green bird keeps company to the imprisoned queen, and tells her he can talk, and he is actually a cursed prince. The fantastic children's grandmother sets them on their quest for the fabulous items: the singing apple and the dancing waters.[94]

France

There are many oral variants collected and analysed by folklorists, found, for instance, in Brittany and Lorraine:[62] Les trois filles du boulanger, or L’eau qui danse, le pomme qui chante et l’oiseau de la verité ("The Three Daughters of the Baker, or water that dances, the fruit that sings and the bird of truth"),[95] and Les Deux Fréres et la Soeur ("The Two Brothers and their Sister"), a tale heavily influenced by Christian tradition[96] - both collected by François-Marie Luzel; La mer qui chante, la pomme qui danse et l’oisillon qui dit tout ("The Singing Sea, The Dancing Apple and The Little Bird that tells everything"), recorded by Jean-François Bladé, from Gascony;[97] La branche qui chante, l’oiseau de vérité et l’eau qui rend verdeur de vie ("The singing branch, the bird of truth and the water of youth"), by Henri Pourrat; L'oiseau qui dit tout, a tale from Troyes collected by Louis Morin;[98] a tale from the Ariège region, titled L'Eau qui danse, la pomme qui chante et l’oiseau de toutes les vérités ("The dancing water, the singing apple and the bird of all truths");[99] a variant from Poitou, titled Les trois lingêres, by René-Marie Lacuve;[100] a version from Limousin (La Belle-Étoile), by J. Plantadis;[101] and a version from Sospel, near the Franco-Italian border (L'oiseau qui parle), by James Bruyn Andrews.[102]

Emmanuel Cosquin collected a variant from Lorraine titled L'oiseau de vérité ("The Bird of Truth"),[103] which is the name used by French academia to refer to the tale.[104]

A tale from Haute-Bretagne, collected by Paul Sébillot (Belle-Étoile), is curious in that if differs from the usual plot: the children are still living with their mother, when they, on their own, are spurred on their quest for the marvelous items.[105] Sébillot continued to collect variants from across Bretagne: Les Trois Merveilles ("The Three Wonders"), from Dinan.[106]

A variant from Provence, in France, collected by Henry Carnoy (L'Arbre qui chante, l'Oiseau qui parle et l'Eau d'or, or "The tree that sings, the bird that speaks and the water of gold"), has the youngest daughter, the princess, marry an enchanted old man she meets in her journey and who gives her advice on how to obtain the items.[107]

An extended version, almost novella-length, has been collected from a Breton source and translated into French, by Gabriel Milin and Amable-Emmanuel Troude, called L'Oiseau de Vérité (Breton: Labous ar wirionez).[108] The tale is curious in that, being divided in three parts, the story takes its time to develop the characters of the king's son and the peasant wife, in the first third. In the second part, the wonder-children are male triplets, each with a symbol on his shoulder: a bow, a spearhead and a sword. The character who helps the youngest prince is an enchanted princess, who, according to a prophecy by her godmother, will marry the youngest son (the hero of the tale).

The tale of La mer qui chante, la pomme qui danse et l’oisillon qui dit tout ("The Singing Sea, The Dancing Apple and The Little Bird that tells everything") preserves the motif of the wonder-children, born with chains of gold "between the skin and muscle of their arms",[109] from Dolopathos and the cycle The Knight of Swan.

In French sources, there have been attested 35 versions of the tale (as of the late 20th century).[110]

Iberian Peninsula

There are also variants in Romance languages: a Spanish version called Los siete infantes, where there are seven children with stars on their foreheads,[111] and a Portuguese one, As cunhadas do rei (The King's sisters-in-law).[112] Both replace the fantastical elements with Christian imagery: the devil and the Virgin Mary.[113]

Modern sources, from the late 20th century and early 21st century, confirm the wide area of distribution of tale across Spain,[114] for instance, in Catalonia.[62] Scholar Montserrat Amores has published a catalogue of the variants of ATU 707 that can be found in Spanish sources (1997).[115] A structural analysis of the tale type in Spanish sources has been published in 1930.[116]

In compilations from the 19th century, collector D. Francisco de S. Maspons y Labros writes four Catalan variants: Los Fills del Rey ("The King's Children"), L'aygua de la vida ("The Water of Life"),[117] Lo castell de irás y no hi veurás and Lo taronjer;[118] Sérgio Hernandez de Soto collected a variant from Extremadura, named El papagayo blanco ("The white parrot");[119] Juan Menéndez Pidal a version from the Asturias (El pájaro que habla, el árbol que canta y el agua amarilla);[120] Antonio Machado y Alvarez wrote down a tale from Andalusia (El agua amarilla);[121] writer Fernán Caballero collected El pájaro de la verdad ("The Bird of Truth");[122] Wentworth Webster translated into English a variant in Basque language (The singing tree, the bird which tells the truth, and the water that makes young)[123]

Some versions have been collected in Mallorca, by Antoni Maria Alcover: S'aygo ballant i es canariet parlant ("The dancing water and the talking canary");[124] Sa flor de jerical i s'aucellet d'or;[125] La Reina Catalineta ("Queen Catalineta"); La bona reina i la mala cunyada ("The good queen and the evil sister-in-law"); S'aucellet de ses set llengos; S'abre de música, sa font d'or i s'aucell qui parla ("Tree of Music, the Fountains of Gold and the Bird that Talks").[126]

A variant in verse format has been collected from the Madeira Archipelago.[127] Another version has been collected in the Azores Islands.[128]

British Isles

A singular occurrence of the ATU 707 type is attested in Irish folklore, recorded by Irish folklorist Sean O'Suilleabhain in Folktales of Ireland, under the name The Speckled Bull.[129] In Types of the Irish Folktale (1963), by the same author, he lists a variant titled Uisce an Óir, Crann an Cheoil agus Éan na Scéalaíochta.[130]

Greece and Mediterranean Area

Fairy tale scholars point that at least 265 Greek versions have been collected and analysed by Angéloupoulou and Brouskou.[131][132] Scholar and writer Teófilo Braga points that a Greek literary version ("Τ’ αθάνατο νερό"; English: "The immortal water") has been written by Greek expatriate Georgios Eulampios (K. Ewlampios), in his book Ὁ Ἀμάραντος (German: Amarant, oder die Rosen des wiedergebornen Hellas; English: "Amaranth, or the roses of a reborn Greece") (1843).[133]

Some versions have been analysed by Arthur Bernard Cook in his Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion (five variants),[134] and by W. A. Clouston in his Variants and analogues of the tales in Vol. III of Sir R. F. Burton's Supplemental Arabian Nights (1887)[41] (two variants), as an appendix to Sir Richard Burton's translation of The One Thousand and One Nights.

Two Greek variants alternate between twin children (boy and girl)[135][136] and triplets (two boys and one girl).[137][138][139][140] Nonetheless, the tale's formula is followed to the letter: the wish for the wonder-children, the jealous relatives, the substitution for animals, exposing the children, the quest for the magical items and liberation of the mother.

In keeping with the variations in the tale type, a tale from Athens shows an abridged form of the story: it keeps the promises of the three sisters, the birth of the children with special traits (golden hair, golden ankle and a star on forehead), and the grandmother's pettiness, but it skips the quest for the items altogether and jumps directly from a casual encounter with the king during a hunt to the unveiling of truth during the king's banquet.[141][142]

Albanian variants can be found in the works of many folklorists of the 19th and 20th centuries: a variant collected in the village of Zagori in Epirus, by J. G. Von Hahn in his Griechische und Albanische Märchen (Leipzig, 1864), and analysed by Arthur Bernard Cook in his Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion;[143] Auguste Dozons's Contes Albanais (Paris, 1881) (Tale II: Les Soeurs Jaleuses, or "The Envious Sisters");[144] André Mazon's study on Balkan folklore, with Les Trois Soeurs;[145] linguist August Leskien in his book of Balkan folktales (Die neidischen Schwestern)[146] and Robert Elsie, German scholar of Albanian studies, in his book Albanian Folktales and Legends (The youth and the maiden with stars on their foreheads and crescents on their breasts).[147]

A Maltese variant has been collected by Hans Stumme, under the name Sonne und Mond, in Maltesische Märchen (1904).[148] This tale begins with the ATU 707 (twins born with astronomical motifs/aspects), but the story continues under the ATU 706 tale-type (The Maiden without hands): mother has her hands chopped off and abandoned with her children in the forest. A second Maltese variant was collected by researcher Bertha Ilg-Kössler, titled Sonne und Mond, das tanzende Wasser und der singende Vogel.[149]

Germany and Central Europe

Portuguese folklorist Teófilo Braga, in his annotations, comments that the tale can be found in many Germanic sources,[150] mostly in the works of contemporary folklorists and tale collectors: The Three Little Birds (De drei Vügelkens), by the Brothers Grimm in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (number 96);[151][152] Leaping Water, Speaking Bird and Singing Tree, written down by Heinrich Pröhle in Kinder- und Völksmärchen,[153] Die Drei Königskinder, by Johann Wilhelm Wolf (1845); Der Prinz mit den 7 Sternen ("The Prince with 7 stars"), collected in Waldeck by Louis Curtze,[154] Drei Königskinder ("Three King's Children"), a variant from Hanover collected by Wilhelm Busch;[155] and Der wahrredende Vogel ("The truth-speaking bird"), an even earlier written source, by Justus Heinrich Saal, in 1767.[156] A peculiar tale from Germany, Die grüne Junfer ("The Green Virgin"), by August Ey, mixes the ATU 710 tale type ("Mary's Child"), with the motif of the wonder children: three sons, one born with golden hair, other with a golden star on his chest and the third born with a golden stag on his chest.[157]

A variant where it is the middle child the hero who obtains the magical objects is The Talking Bird, the Singing Tree, and the Sparkling Stream (Der redende Vogel, der singende Baum und die goldgelbe Quelle), published in the newly-discovered collection of Bavarian folk and fairy tales of Franz Xaver von Schönwerth.[158]

A version collected from Graubünden (Vom Vöglein, das die Wahrheit erzählt, or "The little bird that told the truth"), the tale begins in media res, with the box with the children being found by the miller and his wife. When the siblings grow up, they seek the bird of truth to learn their origins, and discover their uncle had tried to get rid of them.[159] Another variant from Oberwallis (canton of Valais) (Die Sternkinder) has been collected by Johannes Jegerlehner, in his Walliser sagen.[160]

A Hungarian variant has the siblings as twins and their grandmother, the old queen, as the villain, as in The Golden Fish, The Wonder-working Tree and the Golden Bird, collected by J. Walker McSpadden in his Fairy Tales of Eastern Europe.[161] Other Hungarian tales fall under the banner of "The Golden-Haired Twins" (Hungarian: Az aranyhajú ikrek):[162] Fee Ilona und der goldhaarige Jüngling ("Lady Ilona and the golden-haired Youth"), of the Brother quests for a Bride format;[163] Die zwei goldhaarigen Kinder ("The Two Children with Golden Hair"), of The Boys With Golden Stars format;[164] Nád Péter ("Schilf-Peter"), a variant of The Tale of Tsar Saltán format.[165] Elisabet Róna-Sklárek has also published comparative commentaries on Hungarian folktales in regards to similar versions in international compilations.[166]

In a variant collected in Austria, by Ignaz and Joseph Zingerle (Der Vogel Phönix, das Wasser des Lebens und die Wunderblume, or "The Phoenix Bird, the Water of Life and the Most beautiful Flower"),[167] the tale acquires complex features, mixing with motifs of ATU "the Fox as helper" and "The Grateful Dead": The twins take refuge in their (unbeknownst to them) father's house, it's their aunt herself who asks for the items, and the fox who helps the hero is his mother.[168] The fox animal is present in stories of the Puss in Boots type, or in the quest for The Golden Bird/Firebird (ATU 550 - Bird, Horse and Princess) or The Water of Life (ATU 551 - The Water of Life), where the fox replaces a wolf who helps the hero/prince.[169]

A variant from Buchelsdorf, when it was still part of Austrian Silesia, (Der klingende Baum) has the twins raised as the gardener's sons and the quest for the water-tree-bird happens in order to improve the king's garden.[170]

Scandinavia

One version collected in Iceland can be found in Ján Árnuson's Íslenzkar þjóðsögur og æfintýri, published in 1864 (Bóndadæturnar), translated as "The Story of The Farmer's Three Daughters", in Icelandic Legends (1866); in Isländische Märchen (1884), with the title Die Bauerntöchter,[171] or in Die neuisländischen Volksmärchen (1902), by Adeline Rittershaus (Die neidischen Schwestern).[172]

Other versions have been recorded from Danish and Swedish sources:[59] a Swedish version, named Historie om Talande fogeln, spelande trädet och rinnande wattukällan (or vatukällan);[173] another Scandinavian variant, Om i éin kung in England;[174] Danish variant Det springende Vand og det spillende Trae og den talende Fugl ("The leaping water and the playing tree and the talking bird"), collected by Evald Tang Kristensen;[175] Den forskudte dronning og den talende fugl, det syngende træ, det rindende vand ("The Disowned Queen and the Talking Bird, the Singing Tree, the Flowing Water"), present in Jyske folkeminder, Vol. V, mentioned by Astrid Lunding.[176]

A Finnish variant, called Tynnyrissä kaswanut Poika (The boy who grew in a barrel), follows the Tale of Tsar Saltan format: peasant woman promises the King three sets of triplets in each pregnancy, but her envious older sisters substitute the boys for animals. She manages to save her youngest child but both are cast into the sea in a barrel.[177] A second variant veers close to the Tale of Tsar Saltán format (Naisen yhdeksän poikaa, or "The woman's nine children"),[178] but the reunion with the kingly father does not end the tale; the two youngest brothers journey to rescue their siblings from an avian transformation curse.

Other Finnish variants can be found in Eero Salmelainen's Suomen kansan satuja ja tarinoita.[179] A version was translated into English with the name Mielikki and her nine sons.[180]

Another Finnish variant, from Ingermanland, has been collected in Finnische und Estnische Volksmärchen (Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne, or "Brother and Sister, and the golden-haired sons of the King").[181]

Baltic Region

Jonas Basanavicius collected a few variants in Lithuanian compilations, including the formats The Boys with the Golden Stars and Tale of Tsar Saltan. Its name in Lithuanian folktale compilations is Nepaprasti vaikai[182] or Trys auksiniai sûnûs.

The work of Latvian folklorist Peteris Šmidts, beginning with Latviešu pasakas un teikas ("Latvian folktales and fables") (1925-1937), records 33 variants of the tale type. Its name in Latvian sources is Trīs brīnuma dēli or Brīnuma dēli.

A thorough study on Estonian folktales (among them, the ATU 707 tale type) was conducted by researchers at Tartu University and published in two volumes (in 2009 and in 2014).[183]

Russia and Eastern Europe

Slavicist Karel Horálek published an article with an overall analysis of the ATU 707 type in Slavic sources.[184]

The earliest version in Russian was recorded in Старая погудка на новый лад (1794-1795), with the name Сказка о Катерине Сатериме ("The Tale of Katarina Saterima").[185][186] Another compilation in the Russian language that precedes both The Tale of Tsar Saltan and Afanasyev's tale collection was Сказки моего дедушки (1820), which recorded a variant titled Сказка о говорящей птице, поющем дереве и золо[то]-желтой воде.[186]

The fairy tale in verse The Tale of Tsar Saltan, written by renowned Russian author Alexander Pushkin and published in 1831, is another variant of the tale, and the default form by which the ATU 707 is known in Russian and Eastern European academia.[187] It tells the tale of three sisters, the youngest of which is chosen by the eponymous Tsar Saltan as his wife, to the blind jealousy of her two elder sisters. While the royal husband is away at war, she gives birth to Prince Gvidon Saltanovitch, but her sisters conspire to cast mother and child to the sea in a barrel. Both she and the baby wash ashore in the island of Buyan, where Prince Gvidon grows up to an adult male. After a series of adventures - and with the help of a magical princess in the form of a swan (Princess Swan), Prince Gvidon and his mother reunite with Tsar Saltan, as Princess Swan and Prince Gvidon marry.

Russian folklorist Alexander Afanasyev collected seven variants, divided in two types: The Children with Calves of Gold and Forearms of Silver (in a more direct translation: Up to the Knee in Gold, Up to the Elbow in Silver),[188][189] and The Singing Tree and The Speaking Bird.[190][191] Two of his tales have been translated into English: The Singing-Tree and the Speaking-Bird[192] and The Wicked Sisters.[193] In the later, the children are male triplets with astral motifs on their bodies, but there is no quest for the wondrous items.

A version from Poland has been collected by Antoni Józef Glinski ans translated into German (Vom prinzen mit dem Mond auf der Stirn und Sternen auf dem Kopf).[194]

A Czech variant was collected by author Božena Němcová, under the name O mluvícím ptáku, živé vodě a třech zlatých jabloních ("The speaking bird, the water of life and the three golden apples").[195]

A version from Bulgaria was recorded by Václav Florec in 1970, with the name Tři sestry ("Three sisters").[196]

A recent publication (2007) of Slovenian folk tales, collected by Anton Pegan in the 19th century, has a Slovenian variant of the ATU 707, under the name Vod trejh predic.[197][198]

The format of the story The Boys With The Golden Stars seems to concentrate around Eastern Europe: in Romenia;[36][37][199][200] a version in Belarus;[201] in Servia;[202] in the Bukovina region;[203] in Croatia;[204][205] Bosnia,[206] Poland, Ukraine, Czech Republic and Slovakia.[207]

Caucasus Mountains

At least two Armenian versions exist in folktale compilations: The Twins[22] and Cheveux d'argent et Boucles d'or.[208] A variant collected from tellers of Armenian descent in the Delray section of Detroit shows: the king listens to his daughters - the youngest promising the wonder children when she marries; the twins are the king's grandsons; the Brother quests for the bird Hazaran Bulbul and a female interpreter for the bird. When the interpreter is delivered to the Sister, the former requests the Brother to go back to the bird's owner, Tanzara Kanum, and bring the second woman who lives there, so that they may keep company and protect the Sister.[209] A fourth Armenian variant (Théodore le Danseur) places a giant named Barogh Assadour ("Dancing Theodore")[210] in the role of the mystical woman the brother seeks, and this fabled character ends up marrying the sister.[211]

A variant in Avar language is attested in Awarische Texte, by Anton Schiefner.[212]

Two Georgian variants exist in international folktale publications:[213] Die Kinder mit dem Goldschopf ("The children with golden heads")[214] and The Three Sisters and their Stepmother.[215]

Asia

Turkey

Folklorists and tale collectors Wolfram Eberhard and Pertev Naili Boratav, who wrote a thorough study on Turkish tales,[216] list at least 55 versions of the story that exist in Turkish compilations.[217] Part of the Turkish variants follow the Brother Quests for a Bride format: the aunts' helper (witch, maid, midwife, slave) suggests her brother brings home a woman of renowned beauty, who becomes his wife at the end of the story and, due to her supernatural powers, acquits her mother-in-law of any perceived wrongdoing in the king's eyes.[218]

A Turkish variant, translated into German, has twins with golden hair: the male with the symbol of a half-moon, and the female with a bright star, and follow the Brother quests for a Bride format, with the prince/hero seeking Die Feekönigin (The Fairy Queen). This character knows the secrets of the family and instructs the siblings on how to convince the King.[219] Another variant has been collected from the city of Mardin, in the 19th century.[220][221]

Middle East

The tale appears in fairy tale collections of Middle Eastern and Arab folklore,[222] as a possible point of origin or dispersal.[223] One version appears in the collection of The Arabian Nights, by Antoine Galland, named Histoire des deux sœurs jalouses de leur cadette, or The Story of the older sisters envious of their Cadette (cadette or cadet is a French word meaning youngest sibling). The tale contains a mythical bird called Bülbül-Hazar, thus giving the tale an alternate name: Perizade & L'Oiseau Bülbül-Hazar. The heroine, Perizade ou Farizade, also names the tale Farizade au sourire de rose ("Farizade of the rose's smile").[224][225]

A second variant connected to the Arabian Nights compilation is Abú Niyyan and Abú Niyyatayn, part of the frame story The Tale of the Sultan of Yemen and his three sons (The Tale of the King of al-Yaman and his three sons). The tale is divided into two parts: the tale of the father's generation falls under the ATU 613 tale type (Truth and Falsehood), and the sons' generation follows the ATU 707.[226] A third version present in The Arabian Nights is "The Tale of the Sultan and his sons and the Enchanting Bird", a fragmentary version that focuses on the quest for the bird with petrifying powers.[227]

Other versions in Arab-speaking countries that preserve the quest for the bird mention a magical nightingale.[228]

India

An Indian tale, collected by Joseph Jacobs in his Indian Fairy Tales (1892), The Boy who had a Moon on his Forehead and a Star on his Chin, omits the quest for the items and changes the jealous aunts into jealous co-wives of the king, but keeps the wonder-child character (this time, an only child) and the release of his mother.[229][230] Jacobs's source was Maive Stokes's Indian Fairy Tales (1880), with her homonymous tale.[231]

The character of the Boy with the Moon on his forehead reappears in an eponymous tale collected from Bengali (The Boy with the Moon on his Forehead), where the seventh queen begets a boy and a girl, and the jealous co-wives of the king try to eliminate both siblings.[23]

A third variant can be found in The Enchanted Bird, Music and Stream, recorded by Alice Elizabeth Dracott, in Simla Village Tales, or Folk Tales from the Himalayas.[232] This tale follows the general format, but the quest items's descriptors mention no significant magical properties, unlike most variants of the tale.

In true family saga fashion, an Indian tale of certain complexity and extension (Truth's Triumph, or Der Sieg der Wahrheit) tells a story of a Ranee of humble origins, the jealousy of the twelve co-wives, the miraculous birth of her 101 children and their abandonment in the wilderness. In the second part of the tale, the youngest child, a girl, witnesses her brothers' transformation into crows, but she is eventually found and marries a Rajah of a neighboring region. Her child, the prince, learns of his family history and ventures on a quest to reverse his uncles's transformation. At the climax of the story, the boy invites his grandfather and his co-wives and reveals the whole plot, as the family reunites.[233]

James Hinton Knowles collects three varians from Kashmir, in which the number of siblings vary between 4 (three boys, one girl; third son as the hero), 2 (two sons; no quest for the water-tree-bird) and 1 (only male child; quest for tree and its covering; no water, nor bird).[234]

East Asia

Folklorist D. L. Ashliman, in his 1987 study of folktales,[225] lists The Golden Eggplant (黄金の茄子 <<Kin no nasu>>) as a Japanese variant of the tale.[235]

Africa

North Africa

Some versions of the tale have been collected from local storytellers in many regions: two versions have been found in Morocco,[236] one on the Northern area; some have been collected in Algeria,[40] and one of them in the Tell Atlas area,[237] and some in Egypt.[238][239][240][241]

Two versions have been recorded by German ethnographer Leo Frobenius in his Atlantis book collection: Die ausgesetzten Geschwister and Die goldhaarigen Kinder.[242]

In a specific folktale from Egypt (The Promises of the Three Sisters),[243] the male twin is named Clever (name), while the female twin is called Mistress of Beauty, and both quest for the "dancing bamboo, singing water and talking lark". In the El-Schater Mouhammed tale, a variant from Egypt, the Brother is the hero of the story, but the last item of the quest (the bird) is replaced by "a baby or infant who can speak eloquently", as an impossible MacGuffin.

In a Tunisian version (En busca del pájaro esmeralda, or "The quest for the emerald bird"), the older brother is the hero of the story and the singing branch is conflated with the titular emerald bird, which reveals the story at a feast with the Sultan.[244] Another Tunisian version has been collected from oral sources under the name M'hammed, le fils du sultan ("M'hammed, the son of the Sultan").[245]

Central Africa

A version of the tale was found amongst Batanga sources, with the name The Toucan and the Three Golden-Girdled Children, collected by Robert Hamill Nassau and published in the Journal of American Folklore, in 1915.[246]

East Africa

Scholars have attested the presence of the tale type in African sources,[247] such as the East African version collected by Carl Meinhof.[248]

Southern Africa

A tale of the Sotho people (Basotho) with the motif of the wonderful child with a moon on his breast was recorded in The treasury of Ba-suto lore (1908), by Édouard Jacouttet.[249]

Americas

North America

A few versions have been collected from Mexican-American populations living in American states, such as California and New Mexico,[250] and in the Southwest.[251] A variant from Northern New Mexico has been collected by José Manuel Espinosa in the 1930's and published by Joe Hayes in 1998: El pájaro que contaba verdades ("The Bird that spoke the Truth").[252] A variant collected around Los Angeles area has two sons, one golden-haired and the other silver-haired, and a girl with a star on her forehead,[253] while a second variant mixes the ATU 425A ("Quest for The Lost Husband") with ATU 707.[254]

A version from French Canada (Québec) was collected by professor Marius Barbeau and published in the Journal of American Folklore, with the title Les Soeurs Jalouses ("The envious sisters").[255] The tale has inspired Canadian composer Gilles Tremblay to compose his Opéra Féerie L'eau qui danse, la pomme qui chante et l'oiseau qui dit la vérité (2009).[256]

A variant was collected from Tepecano people in the state of Jalisco (Mexico) by J. Alden Mason (Spanish: Los niños coronados; English: "The crowned children") and also published in the Journal of American Folklore.[257]

Central America

Four variants have been collected by Manuel José Andrade, obtained from sources in the Dominican Republic.[258] The tales contain male children as the heroes who perform the quest to learn the truth of their birth.

Other versions are also present in the folklore of Puerto Rico,[259][260] and of Panama.[261]

South America

A Brazilian version has been collected by Brazilian literary critic, lawyer and philosopher Silvio Romero, from his native state of Sergipe and published as Os três coroados ("The three crowned ones") in his Contos Populares do Brazil (1894). In this version, the siblings are born each with a little crown on their heads, and their adoptive mother is the heroine.[262][263]

Folklorist and researcher Berta Elena Vidal de Battini collected eight variants all over Argentina, throughout the years, and published them as part of an extensive compilation of Argentinian folk-tales.[264] An etiological folk tale, collected by Bertha Koessler-Ilg among the Mapuche of Argentina (Dónde y cómo tuvieron origen los colibries, English: "How and why the colibris were created"),[265] holds several similarities with the tale-type.[266] Another variant (La Luna y el Sol) has been collected by Susana Chertudi.[267]

Versions collected in Chile[268] have been grouped under the banner Las dos hermanas envidiosas de la menor ("The two sisters envious of their youngest"): La Luna i el Sol ("Moon and Sun") and La niña con la estrella de oro en la frente ("The girl with the golden star on her forehead").[269] This last tale is unique in that the queen gives birth to female twins: the eponymous girl and her golden-haired sister, and its second part has similarities with Biancabella and the Snake.

See also

- Ancilotto, King of Provino

- Princess Belle-Etoile

- The Three Little Birds

- The Bird of Truth

- The Wicked Sisters

- The Tale of Tsar Saltan

- The Water of Life

- The Pretty Little Calf

- The Green Bird, an Italian commedia dell'arte by Carlo Gozzi (1765)

For a selection of tales that mix the wonder-children motif with the transformation chase of the twins, please refer to:

References

- "Li figghi di lu cavuliciddaru". Fiabe Novelle e Racconti Popolari Siciliani (in Italian). 1. 1875. pp. 316–328. Pitrè lists his informant for this story as [Rosalia] Varrica.

- Crane, Thomas. . . – via Wikisource.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1916). "The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird". European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 51–65.

- See the

- "Der Vogel der Wahrheit 707" [The Bird of Truth 707]. Lexikon der Zaubermärchen (in German). Archived from the original on June 6, 2020.

- "Contos Maravilhosos: Adversários Sobrenaturais (300-99)" (in Portuguese). p. 177. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020.

- Toporkov, Andrei (2018). "'Wondrous Dressing' with Celestial Bodies in Russian Charms and Lyrical Poetry" (PDF). Folklore: Electronic Journal of Folklore. 71: 210. doi:10.7592/FEJF2018.71.toporkov. ISSN 1406-0949. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 6, 2020.

- Bódis, Zoltán (2013). "Storytelling: Performance, Presentations and Sacral Communication". Journal of Ethnology and Folklorsitics. Estonian Literary Museum, Estonian National Museum, University of Tartu. 7 (2): 22. eISSN 2228-0987. ISSN 1736-6518. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020.

- Thompson, Stith (1977). The Folktale. University of California Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-520-03537-2.

- Arthur Bernard, Cook (1914). "Appendix F". Zeus, A Study In Ancient Religion. Volume II, Part II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1003–1019.

- Tomkowiak, Ingrid (1993). Lesebuchgeschichten: Erzählstoffe in Schullesebüchern, 1770-1920 (in German and English). Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 254. ISBN 3-11-014077-2.

- However, Stith Thompson, in his book of Folklore Motifs, indicates that the formula is "a dancing item, a singing item and the bird".

- Arthur Bernard, Cook (1914). "Appendix F". Zeus, A Study In Ancient Religion. Volume II, Part II. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1006–1007.

- Elsie, Robert (2001). A Dictionary of Albanian Religion, Mythology and Folk Culture. NYU Press. pp. 79–81. ISBN 0-8147-2214-8.

- Çabej, Eqrem (1975). Studime gjuhësore: Gjuhë. Folklor. Letërsi. Diskutime (in Albanian). 5. Rilindja. p. 120.

- Robert, Elsie (2001). "The Youth and the Maiden with Stars on their Foreheads and Crescents on their Breasts". Albanian Folktales and Legends. Dukagjini Pub. House.

- "The Youth and the Maiden with Stars". Albanian Literature | Folklore. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020.

- Kirby, W. F. "Additional Notes on the Bibliography of the Thousand and One Nights". Supplemental Nights Volume 6. Archived from the original on June 6, 2020.

- Contes Arabes Modernes (in French and Arabic). Translated by Spitta-Bey, Guillaume. Paris: Maisonneuve & Cie. 1883. pp. 137–151.

- Rahmouni, Aicha (2015). "Text 21: The Talking Bird". Storytelling in Chefchaouen Northern Morocco: An Annotated Study of Oral Transliterations and Translations. Brill. pp. 376–390. ISBN 978-90-04-27740-3.

- Straparola, Giovan Francesco (2012). Breecher, Donald (ed.). The Pleasant Nights - Volume 1. Translated by Waters, W. G. University of Toronto Press. pp. 601–602. ISBN 978-1-4426-4426-7.

- Seklemian, A. G. (1898). "The Twins". The Golden Maiden and Other Folk Tales and Fairy Stories Told in Armenia. New York: The Helmen Taylor Company. pp. 111–122.

- Day, Rev. Lal Behari (1883). "XIX. The boy with the moon on his forehead". Folk-Tales of Bengal. London: McMillan and Co. pp. 236–257.

- Milin, Gabriel; Troude, Amable-Emmanuel (1870). "L'Oiseau de Vérité". Le Conteur Breton (in Breton). Lefournier. pp. 3–63.

- Poestion, J. C. (1884). "Die Bauerntöchter". Isländische Märchen: aus den Originalquellen (in Icelandic and German). Wien: C. Gerold. pp. 192–200.

- Árnason, Jón, ed. (1866). "The story of the farmer's three daughters". Icelandic Legends. Translated by Powell, George E. J.; Magnússon, Eirikur (Second series ed.). London: Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 427–435.

- Carnoy, Henry (1885). "XV L'Arbre qui chante, l'Oiseau qui parle et l'Eau d'or". Contes français (in French). Paris: E. Leroux. pp. 107–113.

- Franzisci, Franz (2006). "Die schwarzen und die weißen Steine". Märchen aus Kärnten (in German). ISBN 978-3-900531-61-4.

- Hoogasian-Villa, Susie (1966). 100 Armenian Tales and Their Folkloristic Relevance. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 492.

- Drower, Ethel Stefana (2006). Folktales of Iraq. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 294. ISBN 0-486-44405-8.

- Johns, Andreas (2010). Baba Yaga: The Ambiguous Mother and Witch of the Russian Folktale. New York: Peter Lang. pp. 244–246. ISBN 978-0-8204-6769-6.

- Róna-Sklarek, Elisabet (1909). "5: Schilf-Peter". Ungarische Volksmärchen [Hungarian folktales] (in German). 2 (Neue Folge ed.). Leipzig: Dieterich. pp. 53–65.

- Löwis of Menar, August von. (1922). "15. Bruder und Schwester und die goldlockigen Königssöhne". Finnische und estnische Volksmärchen [Finnish and Estonian folktales] (in German). Jena: Eugen Diederichs. pp. 53–59.

- Vrkić, Jozo (1997). Hrvatske bajke (in Croatian). Glagol, Zagreb. ISBN 953-6190-04-4.

The tale first published in written form by Rudolf Strohal. - Davidson, Hilda Ellis; Chaudhri, Anna, eds. (2003). A Companion to the Fairy Tale. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer. pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-85991-784-3.

- Schott, Arthur; Schott, Albert (1845). "Die goldenen kinder". Walachische Märchen (in German). Stuttgart and Tübingen: J. C. Cotta'scher Verlag. pp. 121–125.

Collected from Mihaila Poppowitsch in Wallachia - Murray, Eustace Clare Grenville (1854). "Sirte-Margarita". Doĭne: Or, the National Songs and Legends of Roumania. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 106–110.

- Kremnitz, Mite (1882). "Die Zwillingsknaben mit dem goldenen Stern". Rumänische Märchen (in German). Wilhelm Friedrich. pp. 30–42.

- Lang, Andrew. "The Boys with the Golden Stars". The Violet Fairy Book. pp. 299–310.

- Rivière, Joseph (1882). "Les enfants et la chauve-souris". Recueil de contes populaires de la Kabylie du Djurdjura (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. pp. 71–74.

- Clouston, W. F. (1887). Variants and analogues of the tales in Vol. III of Sir R. F. Burton's Supplemental Arabian Nights. pp. 617–648 – via Wikisource.

- Pacha, Yacoub Artin (1895). "XXII. El-Schater Mouhammed". Contes populaires inédits de la vallée du Nil (in French). Paris: J. Maisonneuve. pp. 265–284.

- Lorimer, David Lockhart Robertson; Lorimer, Emily Overend (1919). "The Story of the Jealous Sisters". Persian Tales. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd. pp. 58–62.

- Mickel, Emanuel J.; Nelson, Jan A., eds. (1977). "Texts and Affiliations". La Naissance du Chevalier au Cygne. The Old French Crusade Cycle. 1. Geoffrey M. Myers (essay). University of Alabama Press. p. lxxxxi–lxxxxiii. ISBN 0-8173-8501-0. (Elioxe ed. Mickel Jr., Béatrix ed. Nelson)

- Sun, Uitgeverij (2000) [First published in English in 1998; original Dutch Van Aiol tot de Zwaanridder published 1993 by SUN]. "Seven Sages of Rome". In Gerritsen, Willem P.; Van Melle, Anthony G. (eds.). Dictionary of Medieval Heroes. Translated by Guest, Tanis. The Boydell Press. p. 247. ISBN 0-85115-780-7.

- Schlauch, Margaret (1969) [Originally published 1927]. Chaucer's Constance and Accused Queens. New York: Gordian Press. p. 80.

- Hibbard, Laura A. (1969) [First published 1924]. Medieval Romance in England. New York: Burt Franklin. p. 240–241.

- Istoria della Regina Stella e Mattabruna (in Italian). 1822.

- The Robber with a Witch's Head. Translated by Zipes, Jack. Collected by Laura Gozenbach. Routledge. 2004. p. 217. ISBN 0-415-97069-5.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Stokes, Maive. Indian fairy tales, collected and tr. by M. Stokes; with notes by Mary Stokes. London: Ellis and White. 1880. p. 276

- Liungman, Waldemar (1961). Die schwedischen Volksmärchen (in German). Berlin.

- Юрий Евгеньевич Березкин (2019). ""Skazka o tsare Saltane" (cyuzhet ATU 707) i evraziysko-amerikanskie paralleli" «Сказка о царе Салтане» (cюжет ATU 707) и евразийско-американские параллели [“The Tale of Tsar Saltan” (Tale Type ATU 707) and Eurasian-American Parallels]. Antropologicheskij forum Антропологический форум (in Russian) (43): 89–110. doi:10.31250/1815-8870-2019-15-43-89-110. ISSN 1815-8870. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020.

- Lenz, Rodolfo (1912). Un grupo de consejas chilenas. Los anales de la Universidad de Chile (in Spanish). Tomo CXXIX. Santiago de Chile: Imprenta Cervantes. p. 135.

- Stokes, Maive. Indian fairy tales, collected and tr. by M. Stokes; with notes by Mary Stokes. London: Ellis and White. 1880. pp. 242-243.

- MacCulloch, John Arnott (1905). The childhood of fiction: a study of folk tales and primitive thought. London: John Murray. pp. 57–60.

- Vaitkevičienė, Daiva (2013). "Paukštė, kylanti iš pelenų: pomirtinis persikūnijimas pasakose" [The Bird Rising from the Ashes: Posthumous Transformations in Folktales]. Tautosakos darbai (in Lithuanian) (XLVI): 71–106. ISSN 1392-2831. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020.

- Stokes, Maive. Indian fairy tales, collected and tr. by M. Stokes; with notes by Mary Stokes. London: Ellis and White. 1880. pp. 250-251.

- "This story has the peculiarity, that it occurs in the Arabian Nights as well as in so many European folktales." Jacobs, Joseph. Europa's Fairy Book. 1916. pp. 234-235.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiri (1913). "Di drei Vügelkens". Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- u. hausmärchen der brüder Grimm (in German). Zweiter Band (NR. 61-120). Germany, Leipzig: Dieterich'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung. pp. 380–394.

- Jacobs, Joseph (1916). "Notes: VII. Dancing Water". European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 233–235.

- Braga, Teófilo (c. 1883). . (in Portuguese). Vol. I. pp. 119–120 – via Wikisource.

- Groome, Francis Hindes (1899). "No. 18—The Golden Children". Gypsy folk-tales. London: Hurst and Blackett. pp. 71–72 (footnote).

- Straparola, Giovanni Francesco. "Night the Fourth — The Third Fable". The Facetious Nights of Straparola. 2. Translated by Waters, W. G. pp. 56–88.

- Straparola, Giovanni Francesco (1578). Le tredici piacevoli notti del s. Gio. Francesco Straparola (in Italian). pp. 115–124.

- Sarnelli, Pompeo (1684). "La 'ngannatrice 'ngannata". Posilecheata de Masillo Reppone de Gnanopoli (in Italian). pp. 95–144.

- Haase, Donald, ed. (2008). "Sarnelli, Pompeo (1649–1724)". The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales. 3: Q-Z. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 832. ISBN 978-0-313-33444-3.

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B., ed. (2012). Fairy Tales Framed: Early Forewords, Afterwords, and Critical Words. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-4384-4221-1.

- Chevalier, Máxime (1999). Cuento tradicional, cultura, literatura (siglos XVI-XIX) (in Spanish). Spain, Salamanca: Ediciones Universida de Salamanca. pp. 149–150. ISBN 84-7800-095-X.

- Marcelino, Menéndez y Pelayo (1907). Orígenes de la novela (in Spanish). Tomo II. p. LXXXVIII.

- Trancoso, Gonçalo Fernandes (1974 [ed.1624]). Contos e Histórias de Proveito & Exemplo. Org. de João Palma Ferreira. Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda. [1ª ed., 1575: Fac-simile, 1982, Lisboa, Biblioteca Nacional]. pp. 191-210, Parte II, conto 7.

- The Portuguese tale, in Trancoso's compilation, has been collected in Theófilo Braga's Contos Tradicionaes do Povo Portuguez, under the name

- Bottigheimer, Ruth B., ed. (2012). Fairy Tales Framed: Early Forewords, Afterwords, and Critical Words. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4384-4221-1.

- The Robber with a Witch's Head. Translated by Zipes, Jack. Collected by Laura Gozenbach. Routledge. 2004. p. 222. ISBN 0-415-97069-5.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Robert, Raymonde (Jan 1991). "L'infantilisation du conte merveilleux au XVIIe siècle". Littératures classiques (in French) (14): 33–46. doi:10.3406/licla.1991.1267. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020.

- As referenced by Vittorio Imbrianni. Imbriani, Vittorio. La Novellaja Fiorentina. Italia, Firenze: Coi tipi di F. Vigo. 1887. p. 97.

- Targioni, Tozzetti, G. "Saggio di Novelline, Canti ed Usanze popolari della Ciociaria". In: Curiosità popolari tradizionali. Vol X. Palermo: Libreria Internazionale. 1891. pp. 10-13.

- Mango, Francesco. "Novelline popolari Sarde". In: Curiosità popolari tradizionali. Vol IX. Palermo: Libreria Internazionale. 1890. pp. 62-64 and 125-127.

- Imbriani, Vittorio. La Novellaja Fiorentina. Italia, Firenze: Coi tipi di F. Vigo. 1887. pp. 125-136.

- Imbriani, Vittorio. La Novellaja Fiorentina. Italia, Firenze: Coi tipi di F. Vigo. 1887. pp. 81-124.

- Nerucci, Gherardo. Sessanta novelle popolari montalesi: circondario di Pistoia. Italy, Firenze: Successori Le Monnier. 1880. pp. 195-205 and pp. 238-247.

- Anderton, Isabella Mary. Tuscan folk-lore and sketches, together with some other papers. London: A. Fairbairns. 1905. pp. 55-64.

- Imbriani, Vittorio. La Novellaja Milanese: Esempii e Panzale Lombarde raccolte nel milanese. Bologna. 1872. pp. 78-79.

- Sicilianische Märchen: Aus dem Volksmund gesammelt, mit Anmerkungen Reinhold Köhler's und einer Einleitung hrsg. von Otto Hartwig. 2 Teile. Leipzig: Engelmann. 1870.

- Comparetti, Domenico. Novelline popolari italiane. Italia, Torino: Ermano Loescher. 1875. pp. 23-31.

- Comparetti, Domenico. Novelline popolari italiane. Italia, Torino: Ermano Loescher. 1875. pp. 117-124.

- Finamore, Gennaro. Tradizioni popolari abruzzesi. Vol. I (Parte Prima). Italy, Lanciano: Tipografia di R. Carabba. 1882. pp. 192-195.

- Visentini, Isaia, Fiabe mantovane (Italy, Bologna: Forni, 1879), pp. 205-208

- de Gubernatis, Angelo. Le novelline di Santo Stefano. Italia, Torino: Presso Augusto Federio Negro Editore. 1869. pp. 37-40.

- For the sake of convenience, the three wonder-children are born with cheveux d'or et dents d'argent ("golden hair and silver teeth"), and they must seek the l'eau qui danse, l'arbre qui joue et le petit oiseau qui parle ("the dancing water, the playing tree and the little speaking bird").

- De Gubernatis, Angelo. La mythologie des plantes; ou, Les légendes du règne végétal. Tome Second. Paris: C. Reinwald. 1879. pp. 224-226.

- Discoteca di Stato (1975). Alberto Mario Cirese; Liliana Serafini (eds.). Tradizioni orali non cantate: primo inventario nazionale per tipi, motivi o argomenti [Oral Not Sung Traditions: First National Inventory by Types, Reasons or Topics] (in Italian and English). Ministero dei beni culturali e ambientali. pp. 152–154.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gozzi, Carlo (1989), Five Tales for the Theatre, Translated by Albert Bermel; Ted Emery. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 239–40. ISBN 0226305791.

- El-Etr, Eurydice. "A la recherche du personnage tragique dans les Fiabe de Carlo Gozzi". In: Arzanà 14, 2012. Le Personnage tragique. Littérature, théâtre et opéra italiens, sous la direction de Myriam Tanant. pp. 95-118. doi:10.3406/arzan.2012.989,

- The Pleasant Nights - Volume 1. Edited with Introduction and Commentaries by Donald Beecher. Translated by W. G. Waters. University of Toronto Press. 2012. pp. 597 seq.

- Luzel, François-Marie. Contes populaires de Basse-Bretagne - Tome I. France, Paris: Maisonneuve Frères et Ch. Leclerc. 1887. pp. 277-295.

- Luzel, François-Marie. Légendes chrétiennes de la Basse-Bretagne. France, Paris: Maisonneuve. 1881. pp. 274-291.

- Bladé, Jean-François. Contes populaires de la Gascogne. France, Paris: Maisonneuve frères et Ch. Leclerc. 1886. pp. 67-84.

- "iii. L'oiseau qui dit tout". Morin, Louis. "Contes troyes". In: Revue des Traditions Populaires. Tome V. No. 12 (15 Décembre 1890). 1890. pp. 735-739.

- Joisten, Charles. "Contes folkloriques de L'Ariège". In: Folklore. Revue trimestralle. Tome XII. 17me année, Nº 4. Hiver 1954. pp. 7-16.

- Lacuve, René-Marie. Contes Poitevins. In: Revue de Traditions Populaires. 10e. Année. Tome X. Nº 8. Août 1895. pp. 479-487.

- Plantadis, J. Contes Populaires du Limousin. In: Revue de Traditions Populaires. 12e Anné. Tome XII. Nº 10. Octobre 1897. pp. 535-537.

- Andrews, James Bruyn. Contes ligures, traditions de la Rivière. Paris, E. Leroux. 1892. pp. 193-198.

- Cosquin, Emmanuel. Contes populaires de Lorraine comparés avec les contes des autres provinces de France et des pays étrangers, et précedés d'un essai sur l'origine et la propagation des contes populaires européens. Tome I. Deuxiéme Tirage. Paris: Vieweg. 1887. pp. 186-189.

- Delarue, Paul et Ténèze, Marie-Louise. Le Conte populaire français. Catalogue raisonné des versions de France et des pays de langue française d'outre-mer Nouvelle édition en un seul volume, Maisonneuve & Larose. 1997 ISBN 2-7068-1277-X

- Sébillot, Paul. Contes de Haute-Bretagne. Paris: Lechevalier Editeur. 1892. pp. 21-22.

- In: Revue de Traditions Populaires. 24e Année. Tome XXIV. Nº 10 (Octobre 1909). pp. 382-384.

- Carnoy, Henry. Contes français. France, Paris: E. Leroux. 1885. pp. 107-113.

- Milin, Gabriel, et. Troude, Amable-Emmanuel. Le Conteur Breton. Lebournier. 1870. pp. 3-63.

- The Pleasant Nights - Volume 1. Edited with Introduction and Commentaries by Donald Beecher. Translated by W. G. Waters. University of Toronto Press. 2012. pp. 594-595.

- Marais, Jean-Luc. "Littérature et culture «populaires» aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles". In: Annales de Bretagne et des pays de l'Ouest. Tome 87, numéro 1, 1980. p. 100. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/abpo.1980.3011] ; www.persee.fr/doc/abpo_0399-0826_1980_num_87_1_3011

- Cuentos Populares Españoles. Aurelio M. Espinosa. Stanford University Press. 1924. pp. 234-236

- Contos Tradicionais do Povo Português. Vol. I. Teófilo Braga. Edições Vercial. 1914. pp. 118-119.

- The Pleasant Nights - Volume 1. Edited with Introduction and Commentaries by Donald Beecher. Translated by W. G. Waters. University of Toronto Press. 2012. pp. 600-601.

- Atiénzar García, Mª del Carmen. Cuentos populares de Chinchilla. España, Albacete: Instituto de Estudios Albacetenses "Don Juan Manuel". 2017. pp. 341-343. ISBN 978-84-944819-8-7

- Amores, Monstserrat. Catalogo de cuentos folcloricos reelaborados por escritores del siglo XIX. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, Departamento de Antropología de España y América. 1997. pp. 118-120. ISBN 84-00-07678-8

- Boggs, Ralph Steele. Index of Spanish folktales, classified according to Antti Aarne's "Types of the folktale". Chicago: University of Chicago. 1930. pp. 81-82.

- Maspons y Labrós, Francisco. Folk-lore catalá. Cuentos populars catalans. Barcelona: Llibreria de Don Alvar Verdaguer. 1885. pp. 38-43 and pp. 81-89.

- Maspons y Labrós, Francisco. Lo Rondallayre: Cuentos Populars Catalans. Barcelona: Llibreria de Don Alvar Verdaguer. 1871. pp. 60-68 and 107-111.

- Hernandez de Soto, Sergio. Folk-lore español: Biblioteca de las tradiciones populares españolas. Tomo X. Madrid: Librería de Fernando Fé. 1886. pp. 175-185.

- Menéndez Pidal, Juan. Poesía popular, colección de los viejos romances que se cantan por los asturianos en la danza prima, esfoyazas y filandones, recogidos directamente de boca del pueblo. Madrid: Impr. y Fund. de los Hijos de J. A. García. 1885. pp. 342-344.

- Machado y Alvarez, Antonio. El folklore andaluz: revista de cultura tradicional. Sevilla, Andalucía: Fundación Machado. 1882. pp. 305-310.

- Caballero, Fernán. Cuentos, oraciones, adivinas y refranes populares e infantiles. Leipzig: Brockhaus. 1878. pp. 31-43.

- Webster, Wentworth. Basque legends. London: Griffith and Farran. 1879. pp. 176-181 (footnotes on pages 181-182).

- Alcover, Antoni Maria. Aplec de rondaies mallorquines. Tom VI. Segona Edició. Ciutat de Mallorca: Estampa de N' Antoni Rotger. 1922. pp. 79-95.

- Alcover, Antoni Maria. Aplec de rondaies mallorquines. Tom VII. Sóller: Estampa de "La Sinceridad". 1916. pp. 269-305.

- Carazo, C. Oriol. "Els primers treballs catalogràfics". In: Estudis de LLengua i Literatura Catalanes. XLIII. Miscel-lània Giuseppe Tavani. Barcelona: Publicacions de l'Abadia de Montserrat. 2001. pp. 193-200. ISBN 84-8415-305-3

- Azevedo, Alvaro Rodrigues de. Romanceiro do archipelago da Madeira. Funchal: "Voz do Povo". 1880. pp. 391-431.

- "The Listening King". In: Eells, Elsie Spicer. The Islands of Magic: Legends, Folk and Fairy Tales from the Azores. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. 1922.

- Folktales of Ireland. Edited by Sean O'Sullivan. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1966. pp. 117-132. ISBN 0-226-63998-3 For an analysis and classification of the tale, see: p. 267 and p. 305.

- Ó Súilleabháin; Christiansen. The Types of the Irish Folktale. Helsinki. 1963. p. 141.

- Megas, G.A.; Angelopoulos, A.; Brouskou, Ai; Kaplanoglou, M., and Katrinaki, E. Catalogue of Greek Magic Folktales. Helsinki: Academia Scientiarum Fennica. 2012. pp. 85-134.

- Krauss, Friedrich Salomo. Volkserzählungen der Südslaven: Märchen und Sagen, Schwänke, Schnurren und erbauliche Geschichten. Austria: Vienna: Böhlau Verlag Wien. 2002. p. 617. ISBN 3-205-99457-4

- Eulampios, Georgios. Ὁ Ἀμάραντος. St. Petersburg. 1843. pp. 76-134.

- Cook, Arthur Bernard. Zeus, a Study in Ancient Religion. Cambridge University Press. 1925. pp. 1003-1019.