Swan maiden

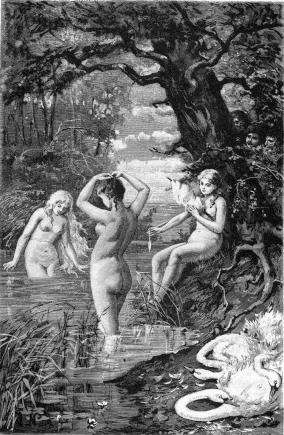

The swan maiden is a mythical creature who shapeshifts from human form to swan form.[1] The key to the transformation is usually a swan skin, or a garment with swan feathers attached. In folktales of this type, the male character spies the maiden, typically by some body of water (usually bathing), then snatches away the feather garment (or some other article of clothing), which prevents her from flying away (or swimming away, or renders her helpless in some other manner), forcing her to become his wife.[2]

There are parallels around the world, notably the Völundarkviða[3] and Grimms' Fairy Tales KHM 193 "The Drummer".[4] There are also many parallels involving creatures other than swans.

Legend

Typical legend

The folktales usually adhere to the following basic plot. A young, unmarried man steals a magic robe made of swan feathers from a swan maiden so that she will not fly away, and marries her. Usually she bears his children. When the children are older they sing a song about where their father has hidden their mother's robe, or one asks why the mother always weeps, and finds the cloak for her, or they otherwise betray the secret. The swan maiden immediately gets her robe and disappears to where she came from. Although the children may grieve her, she does not take them with her.

If the husband is able to find her again, it is an arduous quest, and often the impossibility is clear enough so that he does not even try.

Germanic legend

The stories of Wayland the Smith describe him as falling in love with Swanhilde, a Swan Maiden, who is the daughter of a marriage between a mortal woman and a fairy king, who forbids his wife to ask about his origins; on her asking him he vanishes. Swanhilde and her sisters are however able to fly as swans. But wounded by a spear, Swanhilde falls to earth and is rescued by the master-craftsman Wieland, and marries him, putting aside her wings and her magic ring of power. Wieland's enemies, the Neidings, under Princess Bathilde, steal the ring, kidnap Swanhilde and destroy Wieland's home. When Wieland searches for Swanhilde, they entrap and cripple him. However he fashions wings for himself and escapes with Swanhilde as the house of the Neidings is destroyed.

Another occurrence of the maiden with the magic swan-shirt that allows her avian transformation is the story of valkyrie[5] Brynhild.[6] In the Völsunga saga, King Agnar withholds Brynhild's magical swan shirt, thus forcing her into his service as his enforcer.[7]

Other fiction

The swan maiden has appeared in numerous items of fiction, including the ballet Swan Lake, in which a young princess, Odette and her maidens are under the spell of an evil sorcerer, Von Rothbart, transforming them into swans by day. By night, they regain their human forms and can only be rescued if a young man swears eternal love and faithfulness to the Princess. When Prince Siegfried swears his love for Odette, the spell can be broken, but Siegfried is tricked into declaring his love for Von Rothbart's daughter, Odile, disguised by magic as Odette, and all seems lost. But the spell is finally broken when Siegfried and Odette drown themselves in a lake of tears, uniting them in death for all eternity. While the ballet's revival of 1895 depicted the swan-maidens as mortal women cursed to turn into swans, the original libretto of 1877 depicted them as true swan-maidens: fairies who could transform into swans at will.[8] Several animated movies based on the ballet, including The Swan Princess and Barbie of Swan Lake depict the lead heroines as being under a spell and both are eventually rescued by their Princes.

The magical swan also appears in Russian poem The Tale of Tsar Saltan (1831), by Alexander Pushkin. The son of the titular Tsar Saltan, Prince Gvidon and his mother are cast in the sea in a barrel and wash ashore in a mystical island. There, the princeling grows up in days and becomes a fine hunter. Prince Gvidon and his mother begin to settle in the island thanks to the help of a magical swan called Princess Swan, and in the end of the tale she transforms into a princess and marries Prince Gvidon.[9]

Another occurrence of the motif in Russian folklore exists in Sweet Mikáilo Ivánovich the Rover: Mikailo Ivanovich goes hunting and, when he sets his aim on a white swan, it pleads for its life. Then, the swan transforms into a lovely maiden, Princess Márya, whom Mikail falls in love with.[10][11]

In the Irish Mythological Cycle of stories, in the tale of The Wooing of Étaine, a similar test involving the recognition of the wife among lookalikes happens to Eochu Airem, when he has to find his beloved Étaine, who flew away in the shape of a swan.[12] A second tale of a maiden changing into a swan is the story of hero Óengus, who falls in love with Caer Ibormeith, in a dream.

A version of the plot of the Swan Maiden happens in Swabian tale The Three Swans (Von drei Schwänen): a widowed hunter, guided by an old man of the woods, secures the magical garment of the swan-maiden and marries her. Fifteen years pass, and his second wife finds her swan-coat and flies away. The hunter trails after her and reaches a castle, where his wife and her sisters live. The swan-maiden tells him that he must pass through arduous trials in the castle for three nights, in order to break the curse cast upon the women.[13] The motif of staying overnight in an enchanted castle echoes the tale of The Youth who wanted to learn what Fear was (ATU 326).

A variant of the swan maiden narrative is present in the work of Johann Karl August Musäus,[14][15] a predecessor to the Brothers Grimm's endeavor in the early 1800s. His Volksmärchen der Deutschen contains the story of Der geraubte Schleier ("The Stolen Veil").[16] A French translation ("Voile envolé") can be found in Contes de Museäus (1826).[17] In a short summary: an old hermit, who lives near a lake of pristine water, rescues a young Swabian soldier; during a calm evening, the hermit reminisces about an episode of his adventurous youth when he met in Greece a swan-maiden, descended from Leda and Zeus themselves - in the setting of the story, the Greco-Roman deities were "genies" and "fairies". The hermit explains the secret of their magical garment and how to trap one of the ladies. History repeats itself as the young soldier sets his sights on a trio of swan maidens who descend from heavens to bathe in the lake.

The character of the swan-maiden also appears in an etiological tale from Romania about the origin of the swan,[18] and a ballad with the same theme.[19]

Swedish writer Helena Nyblom explored the theme of a swan maiden who loses her feathery cloak in Svanhammen (The Swan Suit), published in 1908, in Bland tomtar och troll (Among Gnomes and Trolls), an annual anthology of literary fairy tales and stories.

The usual plot involves a magical bird-maiden that descends from heavens to bathe in a lake. However, there are variants where the maiden and/or her sisters are princesses under a curse.[20]

Male versions

The fairytale The Six Swans could be considered a male version of the swan maiden, where the swan skin isn't stolen but a curse, similar to The Swan Princess. An evil step-mother cursed her 6 stepsons with swan skin shirts that transform them into swans, which can only be cured by six nettle shirts made by their younger sister. Similar tales of a parent or a step-parent cursing their (step)children are the Irish legend of The Children of Lir, and The Wild Swans, a literary fairy tale by Danish author Hans Christian Andersen.

An inversion of the story (humans turning into swans) can be found in the Dolopathos: a hunter sights a (magical) maiden bathing in a lake and, after a few years, she gives birth to septuplets (six boys and a girl), born with gold chains around their necks. After being expelled by their grandmother, the children bathe in a lake in their swan forms, and return to human form thanks to their magical chains.

Another story of a male swan is Prince Swan (Prinz Schwan), an obscure tale collected by the Brothers Grimm in the very first edition of their Kinder- und Hausmärchen (1812), but removed from subsequent editions.[21]

Folklore motif and tale types

Established folkloristics does not formally recognize "Swan Maidens" as a single Aarne-Thompson tale type. Rather, one must speak of tales that exhibit Stith Thompson motif index "D361.1 Swan Maiden",[22] which may be classed AT 400, 313,[23][24] or 465A.[4] Compounded by the fact that these tale types have "no fewer than ten other motifs" assigned to them, the AT system becomes a cumbersome tool for keeping track of parallels for this motif.[25] Seeking an alternate scheme, one investigator has developed a system of five Swan Maiden paradigms, four of them groupable as a Grimm tale cognate (KHM 193, 92, 93, and 113) and the remainder classed as the "AT 400" paradigm.[25] Thus for a comprehensive list of the most starkly-resembling cognates of Swan Maiden tales, one need only consult Bolte and Polívka's Anmerkungen to Grimm's Tale KHM 193[26] the most important paradigm of the group.[27]

Each of them using different methods, i.e. observation of the distribution area of the Swan Maiden type or use of phylogenetic methods to reconstruct the evolution of the tale, Gudmund Hatt, Yuri Berezkin and Julien d'Huy independently showed that this folktale would have appeared during the Paleolithic period, in the Pacific Asia, before spreading in two successive waves in America. In addition, Yuri Berezkin and Julien d'Huy showed that there was no mention of migratory birds in the early versions of this tale (this motif seems to appear very late).[28][29]

Animal wife motif

Antiquity and origin

It has been suggested the romance of apsara Urvasi and king Pururavas, of ancient Sanskrit literature, may be one of the oldest forms (or origin) of the Swan-Maiden tale.[30][31]

The antiquity of the swan-maiden tale was suggested in the 19th century by Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould, postulating an origin of the motif before the separation of the Proto-Indo-European language, and, due to the presence of the tale in diverse and distant traditions (such as Samoyedic and Native Americans), there was a possibility that the tale may be even older.[32] Another theory was supported by Charles Henry Tawney, in his translation of Somadeva's Kathasaritsagara: he suggests the source of the motif to be old Sanskrit literature; the tale then migrated to Middle East, and from there as an intermediate point, spread to Europe.[33]

According to Julien d'Huy, such a motif would also have existed in European prehistory and would have a buffalo maiden as a heroine. Indeed, this author finds the motif with four-legged animals in North America and Europe, in an area coinciding with the area of haplogroup X.[34]

Distribution and variants

ATU 402 ("The Animal Bride") group of folktales are found across the world, though the animals vary.[35] The Italian fairy tale "The Dove Girl" features a dove. There are the Orcadian and Shetland selkies, that alternate between seal and human shape. A Croatian tale features a she-wolf.[36] The wolf also appears in the folklore of Estonia and Finland as the "animal bride", under the tale type ATU 409 "The Girl as Wolf".[37][38]

In Africa, the same motif is shown through buffalo maidens. In East Asia, it is also known featuring maidens who transform into various bird species. In Russian fairy-tales there are also several characters, connected with the Swan-maiden, as in The Sea King and Vasilisa the Wise, where the maiden is a dove. In the Japanese legend of Hagoromo, it is a heavenly spirit, or Tennin, whose robe is stolen.[39]

Professor Sir James George Frazer mentions a tale of the Pelew Islands, in the Pacific, about a man who marries a shapeshifting maiden by hiding her fish tail. She bears him a daughter, and, in one occasion, happens to find her fish tail and returns to the ocean soon after.[40]

In mythology

Another related tale is the Chinese myth of the Cowherd and the Weaver Girl,[41][42] in which one of seven fairy sisters is taken as a wife by a cowherd who hid the seven sisters' robes; she becomes his wife because he sees her naked, and not so much due to his taking her robe.[43][44] China and near regions register similar tales close to the swan-maiden story: a tale from "Lew Chew" sources tells of a farmer who owns a pristine fountain of the purest water, when he sights a maiden fair bathing in the water source and possibly soiling it;[45] a second tale narrates the adventures of a prince who meets a Peacock Maiden, in a tale attributed to the Tai people.[46]

One notably similar Japanese story, "The crane wife" (tsuru nyobo), is about a man who marries a woman who is in fact a crane (Tsuru no Ongaeshi) disguised as a human. To make money the crane-woman plucks her own feathers to weave silk brocade which the man sells, but she became increasingly ill as she does so. When the man discovers his wife's true identity and the nature of her illness, she leaves him. There are also a number of Japanese stories about men who married kitsune, or fox spirits in human form (as women in these cases), though in these tales the wife's true identity is a secret even from her husband. She stays willingly until her husband discovers the truth, at which point she must abandon him.[47]

The motif of the swan maiden or swan wife also appears in Southeast Asia, with the tales of Kinnari or Kinnaree (of Thailand) and the love story of Manohara and Prince Sudhana.[48] Another tale is Kasimbaha and Utahagi, from Malay folklore.[49]

Professor and folklorist James George Frazer, in his translation of The Libraries, by Appolodorus, suggests that the myth of Peleus and Thetis seems related to the swan maiden cycle of stories.[50]

In folklore

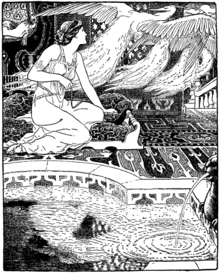

The tale of the swan maiden also appears in the Arab collection of folktales The Arabian Nights,[51] in "The Story of Janshah",[52] a tale inserted in the narrative of The Queen of the Serpents. In a second tale, the story of Hasan of Basrah (Hassan of Bassorah),[53][54] the titular character arrives at a oasis and sees the bird maidens (birds of paradise) undressing their plumages to play in the water.[55]

A story from South Asia also narrates the motif of the swan maiden or bird-princess: Story of Prince Bairâm and the Fairy Bride.[56][57] The motif of the swan maiden is also associated with the Apsaras, of Hinduism.[58][59] The plot of a male character spying on seven celestial maidens (Apsaras) bathing in an earthly lake also happens in a tale from Indonesian history, titled Jaka Tarub and Seven Apsaras, from the island of Java.[60] Other variants from Southeast Asia are The Seven Young Sky Women and Kimod and the Swan Maiden.

Popular culture

Pop culture appearances include modern novels of the fantasy genre such as Three Hearts and Three Lions, television such as Astroboy Episode 5, and video games such as Heroine's Quest. And recently, swan-men in the Anita Blake series, including Kaspar Gunderson. They are also called swan mays or swanmays in fantasy fiction and Dungeons and Dragons. In the Mercedes Lackey book, Fortune's Fool, one swan maiden (named Yulya) from a flock of six is kidnapped by a Jinn. Elven princess Eärwen in The Silmarillion by J.R.R. Tolkien was referred to as the "swan maiden of Alqualonde". The animal bride theme is explored in an animated film called The Red Turtle (2016). Princess Pari Banu from the 1926 German silhouette animation film The Adventures of Prince Achmed appears very similar to a swan maiden, having a peacock skin that transforms her and her handmaids, though she is referred to as a fairy or genie, in the original 1001 Nights.

The anime/manga Ceres, Celestial Legend by Yu Watase is a similar story about an angel whose magic source is stolen as she bathes and she becomes wife to the man who stole it. The story follows one of her descendants now carrying the angel's revenge driven reincarnated spirit inside her.

An episode of children's television programming Super Why adapted the tale of the Swan Maiden.

The eleventh installment of hidden object game series Dark Parables (The Swan Princess and the Dire Tree), published by Eipix mixes the motif of the swan maidens and the medieval tale of The Knight of the Swan.

See also

- Prince as bird (the bird is a prince and woos the maiden)

- Jorinde and Joringel (the maiden is transformed into a bird by the witch)

- The Love for Three Oranges (fairy tale) (the love interest is turned into a bird by the false bride)

- The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples

- Melusine (a mermaid wife)

- Undine (a mermaid wife)

- Knight of the Swan (alternatively named Helias or Lohengrin)

References

- "Literary Sources of D&D". Archived from the original on 2007-12-09. Retrieved 2007-02-23.

- Thmpson (1977), p. 88.

- Thompson (1977), 88, note 2.

- Thompson (1977), p. 88.

- Benoit, Jérémie. "Le Cygne et la Valkyrie. Dévaluation d'un mythe". In: Romantisme, 1989, n° 64. Raison, dérision, Laforgue. pp. 69-84. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/roman.1989.5588]; [www.persee.fr/doc/roman_0048-8593_1989_num_19_64_5588]

- Cox, Marian Roalfe. An introduction to Folk-Lore. London: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1895. p. 120.

- Chantepie de La Saussaye, P. D. The Religion of the Ancient Teutons. Translated from the Dutch by Bert J. Vos. Boston; London: Ginn & Company. 1902. pp. 311-312.

- Wiley 1991, p. 321

- Mazon, André. "Le Tsar Saltan". In: Revue des études slaves, tome 17, fascicule 1-2, 1937. pp. 5-17. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/slave.1937.7637]; [www.persee.fr/doc/slave_0080-2557_1937_num_17_1_7637]

- Hapgood, Isabel Florence. The Epic Songs of Russia. London: C. Scribner's sons. 1886. pp. 214-231.

- Dumézil, Georges. "Les bylines de Michajlo Potyk et les légendes indo-européennes de l'ambroisie". In: Revue des études slaves, tome 5, fascicule 3-4, 1925. pp. 205-237. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/slave.1925.7342]; [www.persee.fr/doc/slave_0080-2557_1925_num_5_3_7342]

- “Etain’s Two Husbands: The Swan Maiden’s Choice.” In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender, by Barbara Fass Leavy, NYU Press, NEW YORK; LONDON, 1994, pp. 277–302. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.11. Accessed 25 Apr. 2020.

- Meier, Ernst. Deutsche Volksmärchen aus Schwaben. Stuttgart. 1852. pp. 38-42.

- Musäus, Johann Karl August. Contes De Musaeus. Tome I. Paris: Moutardier. 1826. p. xiii.

- Musäus, Johann Karl August. Contes De Musaeus. Tome V. Paris: Moutardier. 1826. pp. 127-216.

- Blamires, David (2009). "Musäus and the Beginnings of the Fairytale". Telling Tales: The Impact of Germany on English Children’s Books 1780–1918.

- Contes de Musaeus. Translated by David Ludwig Bourguet. Paris: Moutardier. 1826.CS1 maint: others (link) containing "La Chronique des trois Soeurs", "Richilde", "Les Écuyers de Roland", "Libussa", "La Nymphe de la Fontaine", "Le Trésor du Hartz", "Légendes de Rubezahl", "La Veuve", "L'Enlèvement (Anecdote)", "La Poule aux OEfs d'or", "L'Amour muet", "Le Démon-Amour", "Mélechsala" and "Le Voile enlevé".

- Gaster, Moses. Rumanian bird and beast stories. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. 1915. pp. 246-255.

- Gaster, Moses. Rumanian bird and beast stories. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. 1915. pp. 256-258.

- "Vaino and the Swan Princess". In: Bowman, James Cloyd and Bianco, Margery. Tales from a Finnish tupa. Chicago: A. Whitman & Co. 1964 (1936). pp. 34-41.

- Grimm, Jacob, Wilhelm Grimm, JACK ZIPES, and ANDREA DEZSÖ. "PRINCE SWAN." In: The Original Folk and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm: The Complete First Edition, 194-97. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2014. doi:10.2307/j.ctt6wq18v.66.

- Thompson (1977), p. 90.

- Pyle, Howard; Pyle, Katharine. The Wonder Clock: Or, Four & Twenty Marvellous Tales, Being One for Each Hour of the Day. New York: Printed by Harper & Brothers. 1915 (1887). pp. 231-240,

- "The Irish-American Tale Tradition." In Cinderella in America: A Book of Folk and Fairy Tales, edited by McCarthy William Bernard. p. 386. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. 2007. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2tv86j.21.

- Miller (1987), p. 55.

- Bolte & Polívka (1918), Anmerkungen von KHM, vol. 3, pp.406–417.

- Miller (1987), p. 57.

- Gudmund Hatt (1949). Asiatic influences in American folklore. København: I kommission hos ejnar Munksgaard, p.94-96, 107; Yuri Berezkin (2010). Sky-maiden and world mythology. Iris, 31, pp. 27-39

- Julien d'Huy (2016). Le motif de la femme-oiseau (T111.2.) et ses origines paléolithiques. Mythologie française, 265, pp. 4-11 or here.

- Smith, S. Percy. "Aryan and Polynesian Points of Contact. The Story of Te Niniko," in The Journal of the Polynsian Society. Vol. XIX, no. 2. 1910. pp. 84-88.

- Tuzin, Donald F. The Cassowary's Revenge: The life and death of masculinity in a New Guinea society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1997. pp. 71-72.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine. The book of were-wolves: Being an Account of a Terrible Superstition. London: Smith, Elder and Co. 1865. pp. 178-177.

- Tawney, Charles Henry. The ocean of story, being C.H. Tawney's translation of Somadeva's Katha sarit sagara (or Ocean of streams of story). Book 8. London, Priv. print. for subscribers only by C.J. Sawyer. 1924-1928. Appendix I. p. 234.

- Julien d'Huy (2011). « Le motif de la femme-bison. Essai d'interprétation d'un mythe préhistorique (1ère partie) », Mythologie française, 242, pp. 44-55; et Julien d'Huy (2011). « Le motif de la femme-bison. Essai d'interprétation d'un mythe préhistorique (2ème partie) » Mythologie française, 243, pp. 23-41.

- Cox, Marian Roalfe. An introduction to Folk-Lore. London: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1895. pp. 120-121.

- Wratislaw, Albert Henry. Sixty folk-tales from exclusively Slavonic sources. London: E. Stock. 1887. pp. 290-291.

- METSVAHI, Merili. The Woman as Wolf (AT 409): Some Interpretations of a Very Estonian Folk Tale. Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics, [S.l.], v. 7, n. 2, p. 65-92, jan. 2014. ISSN 2228-0987. Available at: <http://www.jef.ee/index.php/journal/article/view/153>. Date accessed: 25 apr. 2020.

- Thompson, Stith. The Folktale. University of California Press. 1977. p. 96. ISBN 0-520-03537-2

- Iwao Seiichi, Sakamato Tarō, Hōgetsu Keigo, Yoshikawa Itsuji, Akiyama Terukazu, Iyanaga Teizō, Iyanaga Shōkichi, Matsubara Hideichi, Kanazawa Shizue. 18. Hagoromo densetsu. In: Dictionnaire historique du Japon, volume 7, 1981. Lettre H (1) pp. 9-10. [www.persee.fr/doc/dhjap_0000-0000_1981_dic_7_1_890_t2_0009_0000_4]

- Frazer, James George; Apollodorus of Athens The Libraries. Vol. II. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 1921. pp. 385-387.

- Nai-tung TING. A Type Index of Chinese Folktales in the Oral Tradition and Major Works of Non-religious Classical Literature. (FF Communications, no. 223) Helsinki, Academia Scientiarum Fennica, 1978.

- Haase, Donald. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Folktales and Fairy Tales: A-F. Greenwood Publishing Group. 2007. p. 198.

- Miller, Alan L. “Of Weavers and Birds: Structure and Symbol in Japanese Myth and Folktale.” History of Religions, vol. 26, no. 3, 1987, pp. 309–327. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1062378. Accessed 24 Apr. 2020.

- Miller, Alan L. “‘Ame No Miso-Ori Me’ (The Heavenly Weaving Maiden): The Cosmic Weaver in Early Shinto Myth and Ritual.” History of Religions, vol. 24, no. 1, 1984, pp. 27–48. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1062345. Accessed 24 Apr. 2020.

- Dennys, Nicholas Belfield. Folk-lore of China, and its affinities with that of the Aryan Semitic races. London: Trübner. 1876. pp. 140-141.

- Folk Tales from China. Third series. Peking: Foreign Language Press. 1958. pp. 16-46.

- For reference of the animal or mystical bride in Japanese tales, see: Petkova, Gergana. (2009). Propp and the Japanese folklore: applying morphological parsing to answer questions concerning the specifics of the Japanese fairy tale. pp. 597-618. In: Asiatische Studien / Études Asiatiques LXIII, 3. Bern: Peter Lang. 2009. 10.5167/uzh-23802. ISSN 0004-4717

- Schiefner, Anton; Ralston, William Shedden. Tibetan tales, derived from Indian sources. London, K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & co. ltd. 1906. pp. xlviii-l and 44-74.

- Fiske, John. Myths and myth-makers : old tales and superstitions interpreted by comparative mythology. Boston: Hougton, Mifflin. 1896. pp. 162-164.

- Frazer, James George; Apollodorus of Athens The Libraries. Vol. II. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. 1921. pp. 385-387.

- Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam's sons. 1916. p. 241.

- Marzolph, Ulrich; van Leewen, Richard. The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. Vol. I. California: ABC-Clio. 2004. pp. 238-241. ISBN 1-85109-640-X (e-book)

- Jacobs, Joseph. The book of wonder voyages. New York and London: G. P. Putnam's sons. 1919. pp. 127-185.

- Clouston, W. A. Popular tales and fictions: their migrations and transformations. Edinburgh; London: W. Blackwood. 1887. p. 186.

- Wallace, Alfred Russell. "The birds of paradise in the Arabian Nights". In: Independent Review 2. 1904. 379–391, pp. 561–571.

- Swynnerton, Charles. Indian nights' entertainment; or, Folk-tales from the Upper Indus. London: Stock. 1892. pp. 342-347.

- Swynnerton, Charles. Romantic Tales From The Panjab With Indian Nights’ Entertainment. London: Archibald Constable and Co.. 1908. pp. 464-469.

- Tuttle, Hudson; Tuttle, Emma Rood. Stories From Beyond the Borderlands. Berlin Heights, Ohio: The Tuttle Publishing Company. 1910. pp. 175-176.

- Cox, Marian Roalfe. An introduction to Folk-Lore. London: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1895. pp. 120-122.

- Fariha, Inayatul & Choiron, Nabhan. (2017). Female Liberation in Javanese Legend “Jaka Tarub”. KnE Social Sciences. 1. 438. [10.18502/kss.v1i3.766.]

Bibliography

- Baughman, Ernest Warren. Type and Motif-index of the Folktales of England and North America. Indiana University Folklore Series No. 20. The Hague, Netherlands: Mouton & Co 1966. p. 10.

- Baring-Gould, Sabine. Curious myths of the Middle Ages. London: Rivingtons. 1876. pp. 561-578.

- Bihet, Francesca (2019) The Swan-Maiden in Late-Victorian Folkloristics. Fairy Investigation Society Journal. pp. 24–29. http://eprints.chi.ac.uk/4686/

- Boggs, Ralph Steele. Index of Spanish folktales, classified according to Antti Aarne's "Types of the folktale". Chicago: University of Chicago. 1930. pp. 52-53.

- Booss, C. Scandinavian Folk & Fairy Tales: Tales from Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Finland & Iceland. New York: Crown, 1984.

- Bolte, Johannes; Polívka, Jiří (2014) [1918]. "193. Der Trommler". Anmerkungen zu den Kinder- und Hausmärchen der Brüder Grimm (in German). 4. Dieterich. pp. 406–417 (416). ISBN 9783846013885.

- Clouston, W. A. Popular tales and fictions: their migrations and transformations. Edinburgh; London: W. Blackwood. 1887. pp. 182-191.

- Cosquin, Emmanuel. Contes populaires de Lorraine comparés avec les contes des autres provinces de France et des pays étrangers, et précedés d'un essai sur l'origine et la propagation des contes populaires européens. Deuxiéme Tirage. Tome II. Paris: Vieweg. 1887. pp. 16-23.

- Dixon, Roland B. The Mythology Of All Races Vol. IX - Oceanic. Boston, MA: Marshall Jones Company. 1916. pp. 63-63, 138-139, 206, 294-295 and 302.

- Grundtvig, Svend. Danske folkeæventyr, fundne i folkemunde og gjenfortalte. Kjøbenhavn: C.A. Reitzel, 1878. pp. 19-33 ("Jomfru Lene af Sondervand").

- Hahn, Johann Georg von. Griechische und Albanesische Märchen 1-2. München/Berlin: Georg Müller. 1918 [1864]. pp. 336-340.

- Jacobs, Joseph. European Folk and Fairy Tales. New York, London: G. P. Putnam's sons. 1916. pp. 240-242.

- Meier, Ernst. Deutsche Volksmärchen aus Schwaben. Stuttgart. 1852. pp. 38-42 (Von drei Schwänen).

- Miller, Alan L. (1987), "The Swan-Maiden Revisited: Religious Significance of" Divine-Wife" Folktales with Special Reference to Japan", Asian Folklore Studies, 46 (1): 55–86, doi:10.2307/1177885, JSTOR 1177885

- Pino-Saavedra, Yolando. Cuentos Folklóricos De Chile. Tomo I. Santiago, Chile: Editorial Universitaria. 1960. pp. 390-392 (notes on Tale nr. 35).

- Sax, B. The Serpent and the Swan: The Animal Bride in Folklore and Literature. Blacksburg, VA: McDonald & Woodward, 1998.

- Toshiharu, Yoshikawa. 1984. A Comparative Study of the Thai, Sanskrit, and Chinese Swan Maiden. In International Conference on Thai Studies, 197-213. Chulalongkorn University.

- Thompson, Stith (1977), The Folktale, University of California Press, p. 88–93, ISBN 978-0520035379

- Wiley, Roland John (1991). Tchaikovsky's Ballets.

- Zheleznova, Irina. Tales of the Amber Sea: Fairy Tales of the Peoples Of Estonia, Latvia And Lithuania. Moscow: Progress Publishers. 1981 (1974). pp. 174-178.

Further reading

- “Urvaśī and the Swan Maidens: The Runaway Wife.” In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender, by Barbara Fass Leavy, NYU Press, NEW YORK; LONDON, 1994, pp. 33–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.5. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- “Swan Maiden and Incubus.” In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender, by Barbara Fass Leavy, NYU Press, NEW YORK; LONDON, 1994, pp. 156–195. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.8. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- “The Animal Bride.” In Search of the Swan Maiden: A Narrative on Folklore and Gender, by Barbara Fass Leavy, NYU Press, NEW YORK; LONDON, 1994, pp. 196–244. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qg995.9. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- Burson, Anne. “SWAN MAIDENS AND SMITHS: A STRUCTURAL STUDY OF ‘VÖLUNDARKVIÐA.’” Scandinavian Studies, vol. 55, no. 1, 1983, pp. 1–19. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40918267. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- Grange, Isabelle. "Métamorphoses Chrétiennes Des Femmes-cygnes: Du Folklore à L'hagiographie." Ethnologie Française 13, no. 2 (1983): 139-50. Accessed June 13, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/40988761.

- Hartland, E. Sidney. The science of fairy tales: An inquiry into fairy mythology. London: W. Scott. pp. 255-332.

- Hatto, A. T. “The Swan Maiden: A Folk-Tale of North Eurasian Origin?” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, vol. 24, no. 2, 1961, pp. 326–352. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/610171. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- Holmström, H. (1919). Studier över svanjungfrumotivet i Volundarkvida och annorstädes (A study on the motif of the swan maiden in Volundarkvida, with annotations). Malmö: Maiander.

- Kleivan, Inge. The Swan Maiden Myth Among the Eskimo. København: Ejnar Munksgaard. 1962.

- Kovalchuk, Lidia. (2018). Conceptual Integration Of Swan Maiden Image In Russian And English Fairytales. In: Conference: WUT 2018 - IX International Conference “Word, Utterance, Text: Cognitive, Pragmatic and Cultural Aspects”. pp. 68-74. [DOI:10.15405/epsbs.2018.04.02.10.]

- Miller, Alan L. “The Swan-Maiden Revisited: Religious Significance of ‘Divine-Wife’ Folktales with Special Reference to Japan.” Asian Folklore Studies, vol. 46, no. 1, 1987, pp. 55–86. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1177885. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- Newell, W. W. "Lady Featherflight. An English Folk-Tale." The Journal of American Folklore 6, no. 20 (1893): 54-62. Accessed May 18, 2020. doi:10.2307/534281.

- Peterson, Martin Severin. “SOME SCANDINAVIAN ELEMENTS IN A MICMAC SWAN MAIDEN STORY.” Scandinavian Studies and Notes, vol. 11, no. 4, 1930, pp. 135–138. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40915312. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

- Petkova, Gergana. (2009). Propp and the Japanese folklore: applying morphological parsing to answer questions concerning the specifics of the Japanese fairy tale. pp. 597-618. In: Asiatische Studien / Études Asiatiques LXIII, 3. Bern: Peter Lang. 2009. 10.5167/uzh-23802. ISSN 0004-4717

- Tawney, Charles Henry. The ocean of story, being C.H. Tawney's translation of Somadeva's Katha sarit sagara (or Ocean of streams of story). Book 8. London, Priv. print. for subscribers only by C.J. Sawyer. 1924-1928. Appendix I. pp. 213-234.

- Thomson, Stith. Tales of the North American Indians. 1929. pp. 150-174.

- Tuzin, Donald F. The Cassowary's Revenge: The life and death of masculinity in a New Guinea society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1997. pp. 68-89.

- Utley, Francis Lee, Robert Austerlitz, Richard Bauman, Ralph Bolton, Earl W. Count, Alan Dundes, Vincent Erickson, Malcolm F. Farmer, J. L. Fischer, Åke Hultkrantz, David H. Kelley, Philip M. Peek, Graeme Pretty, C. K. Rachlin, and J. Tepper. "The Migration of Folktales: Four Channels to the Americas [and Comments and Reply]." Current Anthropology 15, no. 1 (1974): 5-27. Accessed April 27, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/2740874.

- Waley, Arthur. “An Early Chinese Swan-Maiden Story.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, vol. 22, no. 1/2, 1959, pp. 1–5. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/750555. Accessed 23 Apr. 2020.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |