Tendency of the rate of profit to fall

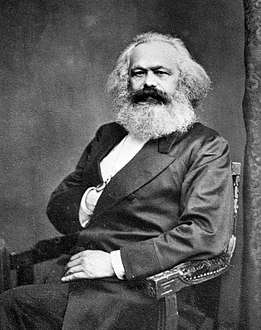

The tendency of the rate of profit to fall (TRPF) is a hypothesis in economics and political economy, most famously expounded by Karl Marx in chapter 13 of Capital, Volume III.[1] Economists as diverse as Adam Smith,[2] John Stuart Mill,[3] David Ricardo[4] and Stanley Jevons[5] referred explicitly to the TRPF as an empirical phenomenon that demanded further theoretical explanation, yet they each differed as to the reasons why the TRPF should necessarily occur.[6]

In his 1857 Grundrisse manuscript, Marx called the TRPF "the most important law of political economy" and sought to give a causal explanation for it in terms of his theory of capital accumulation.[7] In Capital, Volume III, Marx described the TRPF as "the mystery around which the whole of political economy since Adam Smith revolves" and in a letter he called his own TRPF theory "one of the greatest triumphs" over all previous economics.[8] The tendency is already foreshadowed in chapter 25 of Capital, Volume I (on the "general law of capital accumulation"), but in Part 3 of the draft manuscript of Marx's Capital, Volume III, edited posthumously for publication by Friedrich Engels, an extensive analysis is provided.[9]

Geoffrey Hodgson stated that the theory of the TRPF "has been regarded, by most Marxists, as the backbone of revolutionary Marxism. According to this view, its refutation or removal would lead to reformism in theory and practice".[10] Stephen Cullenberg stated that the TRPF "remains one of the most important and highly debated issues of all of economics" because it raises "the fundamental question of whether, as capitalism grows, this very process of growth will undermine its conditions of existence and thereby engender periodic or secular crises".[11]

Marx regarded the TRPF as proof that capitalist production could not be an everlasting form of production since in the end the profit principle itself would suffer a breakdown.[12] However, because Marx never published any finished manuscript on the TRPF himself, because the tendency is hard to prove or disprove theoretically and because it is hard to test and measure the rate of profit, Marx's TRPF theory has been a topic of global controversy for more than a century.

Adam Smith, David Ricardo and Karl Marx

Smith

In Adam Smith's TRPF theory, the falling tendency results from the growth of capital which is accompanied by increased competition. The growth of capital stock itself would drive down the average rate of profit.[13]

Ricardo

Mistakenly interpreting Adam Smith's falling rate of profit theory to be that increased competition drives down the average rate of profit, David Ricardo argued that competition could only level out differences in profit rates on investments in production, but not lower the general profit rate (the grand-average profit rate) as a whole.[14] Apart from a few exceptional cases, Ricardo claimed, the average rate of profit could only fall if wages rose.[15]

Marx

In Capital, Karl Marx criticized Ricardo's idea. Marx argued that, instead, the tendency of the rate of profit to fall is "an expression peculiar to the capitalist mode of production of the progressive development of the social productivity of labor".[16] Marx never denied that profits could contingently fall for all kinds of reasons,[16] but he thought there was also a structural reason for the TRPF, regardless of conjunctural market fluctuations.

Marx argued that technological innovation enabled more efficient means of production. Physical productivity would increase as a result, i.e. a greater output (of use values, i.e., physical output) would be produced, per unit of capital invested. Simultaneously, however, technological innovations would replace people with machinery, and the organic composition of capital would increase. Assuming only labor can produce new additional value, this greater physical output would embody a gradually decreasing value and surplus value, relative to the value of production capital invested. In response, the average rate of industrial profit would therefore tend to decline in the longer term.

It declined in the long run, Marx argued, paradoxically not because productivity decreased, but instead because it increased, with the aid of a bigger investment in equipment and materials.[17] Rosa Luxemburg stated in her 1899 pamphlet Social Reform or Revolution? that:

In the “unhindered” advance of capitalist production lurks a threat to capitalism that is much graver than crises. It is the threat of the constant fall of the rate of profit, resulting not from the contradiction between production and exchange, but from the growth of the productivity of labor itself.[18]

The central idea that Marx had, was that overall technological progress has a long-term "labor-saving bias", and that the overall long-term effect of saving labor time in producing commodities with the aid of more and more machinery had to be a falling rate of profit on production capital, quite regardless of market fluctuations or financial constructions.[19]

Counteracting tendencies

Marx regarded this as a general tendency in the development of the capitalist mode of production. But it was only a tendency, because there are also "counteracting factors" operating which had to be studied as well. The counteracting factors were factors that would normally raise the rate of profit. In his draft manuscript edited by Friedrich Engels (Marx did not publish it himself), Marx cited six of them:[20]

- More intense exploitation of labor (raising the rate of exploitation of workers).

- Reduction of wages below the value of labor power (the immiseration thesis).

- Cheapening the elements of constant capital by various means.

- The growth of a relative surplus population (the reserve army of labor) which remained unemployed.

- Foreign trade reducing the cost of industrial inputs and consumer goods.

- The increase in the use of share capital by joint-stock companies, which devolves part of the costs of using capital in production on others.[21]

Nevertheless, Marx thought the countervailing tendencies ultimately could not prevent the average rate of profit in industries from falling; the tendency was intrinsic to the capitalist mode of production.[22] In the end, none of the conceivable counteracting factors could stem the tendency toward falling profits from production. The capitalist system would age like any other system, and would be able only to compensate for its age, before it left the stage of history for good.

Other influences

There could also be several other factors involved in profitability which Marx did not discuss in detail,[23] including:

- Reductions in the turnover time of industrial capital generally (and especially fixed capital investment).[24]

- Accelerated depreciation and faster throughput.[25]

- The level of price inflation for different types of goods and services.[26]

- Taxes, levies, subsidies and credit policies of governments, interest and rent costs.[27]

- Capital investment into areas of (previously) non-capitalist production, where a lower organic composition of capital prevailed.[28]

- Military wars or military spending causing capital assets to be inoperative or destroyed, or spurring war production (see permanent arms economy).[29]

- Demographic factors.[30]

- Advances in technology and technological revolutions which rapidly reduce input costs.[31]

- Particularly in the era of globalization, the national and international freight rate (shipping, trucking, railfreight, airfreight).

- Substituted natural resource inputs, or marginal increased cost of non-substituted natural resource inputs.[32]

- Consolidation of mature industries into an oligarchy of survivors.[33] Mature industries do not attract new capital because of low returns.[34] Mature companies with large amounts of capital invested and brand recognition can also try to block new competitors in their markets.[35] See also secular stagnation theory.

- The use of credit instruments to reduce capital costs for new production.

The scholarly controversy about the TRPF among Marxists and non-Marxists has continued for a hundred years.[36] There exist nowadays several thousands of academic publications on the TRPF worldwide. However, no book is available which provides an exposition of all the different arguments that have been made. Professor Michael C. Howard stated that "The connection between profit and economic theory is an intimate one. (...) However, a generally accepted theory of profit has not emerged at any stage in the history of economics... theoretical controversies remain intense."[37]

Main criticism of Marx

Marx's interpretation of the TRPF was controversial and has been criticized in three main ways.

Productivity

By raising productivity, labor-saving technologies can increase the average industrial rate of profit rather than lowering it, insofar as fewer workers can produce vastly more output at a lower cost, enabling more sales in less time.[38] Ladislaus von Bortkiewicz stated: "Marx’s own proof of his law of the falling rate of profit errs principally in disregarding the mathematical relationship between the productivity of labour and the rate of surplus value."[39] Jürgen Habermas argued in 1973–74 that the TRPF might have existed in 19th century liberal capitalism, but no longer existed in late capitalism, because of the expansion of "reflexive labor" ("labor applied to itself with the aim of increasing the productivity of labor").[40] Michael Heinrich has also argued that Marx did not adequately demonstrate that the rate of profit would fall when increases in productivity are taken into account.[41]

Contingency

How exactly the average industrial rate of profit will evolve, is either uncertain and unpredictable, or it is historically contingent; it all depends on the specific configuration of costs, sales and profit margins obtainable in fluctuating markets with given technologies.[42] This "indeterminacy" criticism revolves around the idea that technological change could have many different and contradictory effects. It could reduce costs, or it could increase unemployment; it could be labor saving, or it could be capital saving. Therefore, so the argument goes, it is impossible to infer definitely a theoretical principle that a falling rate of profit must always and inevitably result from an increase in productivity.

Perhaps the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to fall might be true in an abstract model, based on certain assumptions, but in reality no substantive, long-run empirical predictions can be made[?]. In addition, profitability itself can be influenced by an enormous array of different factors, going far beyond those which Marx specified[?]. So there are tendencies and counter-tendencies operating simultaneously, and no particular empirical result necessarily and always follows from them[?].

Labor theory of value

Steve Keen argues that since the labor theory of value is wrong, then this obviates the bulk of the critique. Keen observes that the TRPF was based on the idea that only labor can create new value (following the labor theory of value), and that there was a tendency over time for ratio of capital to labor (in value terms) to rise. However, if surplus can be produced by all production inputs, then there is no reason why an increase in the ratio of capital to labor inputs should cause the overall rate of surplus to decline.[43]

20th century Marxist controversies

The 20th century Marxist controversies about the TRPF focused on five issues:

- The relevance of the TRPF for understanding and explaining capitalist economic crises.

- The role of profitability tendencies in the final collapse of capitalism.

- The political significance of the TRPF for the policy of workers' parties.

- The theoretical consistency of the TRPF argument.

- The data about empirical profitability trends in the long term.

In addition, philosophers and economists also discussed the sense in which the TRPF could be considered an economic "law", since it seemed unclear how a necessary tendency could be "necessary" or inevitable, if it was only a tendency, in combination with other tendencies. It was not so easy, to model a situation in which a developmental tendency would, after some time, win through despite a variety of counteracting forces that would ordinarily reduce or cancel out the tendency.[44]

Breakdown controversy

The first big scientific debate about Marx's economic theory, starting in the 1890s, was the so-called "breakdown controversy", in which the tendency toward falling profitability played an important role.[45]

Eduard Bernstein

The debate[46] began to heat up when the veteran German socialist leader Eduard Bernstein claimed that it was wrong to think that "the end was nigh" or that capitalism would collapse through a catastrophic breakdown.[47] He aimed to show with facts and figures that Marx's analysis of the tendencies of capitalism had turned out to be partly wrong.[48] Bernstein believed that Marx's theory therefore had to be revised (this was known as the "revisionist" position).[49] In response, numerous "orthodox" Marxist critics tried to prove that capitalism was necessarily doomed, at least in the long term.[50] This controversy about the fate of the capitalist system still continues.

Henryk Grossman and Vladimir Lenin

From the late 1920s and 1930s onward, classical revolutionary orthodox Marxists like Henryk Grossmann,[51] Louis C. Fraina (alias Lewis Corey) and Paul Mattick argued that at a certain point, the falling rate of profit stops the total mass of profit in the economy from growing altogether, or at least from growing fast enough. This results in a crisis of over-accumulation (or a shortage of surplus value), a drop in new productive investment, and an increase in unemployment, which brakes or stops market expansion. In turn, that leads to a wave of takeovers and mergers to restore profitable production, plus a higher intensity of labor exploitation. In the end, however, after a lot of cycles, capitalism collapses.[52]

This interpretation contrasted with V.I. Lenin’s idea that in the crises of bourgeois society "there is no such thing as an absolutely hopeless situation", since the bourgeoisie can – in principle – always find a way out, even if it takes a war to get there.[53] Lenin regarded the abolition of capitalism as a conscious political act, not as a spontaneous result of the breakdown of the economy. In 1931, two years after publishing his breakdown theory, Grossman qualified his idea more, emphasizing that he did not believe that capitalism had to collapse "by itself" or "automatically"; the objective law of breakdown had to be combined with the subjective factor of the class struggle.[54]

Other theories

Other orthodox Marxists or economists inspired by Marx (including Karl Kautsky, Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky, Nikolai Bukharin, Rudolf Hilferding, Rosa Luxemburg, Vladimir Lenin, Otto Bauer, Fritz Sternberg, Natalia Moszkowska,[55] Oskar Lange, Michał Kalecki, Paul Sweezy, Kei Shibata,[56] Kozo Uno, Nobuo Okishio and Makoto Itoh) provided alternative crisis theories, focusing variously on the anarchy of capitalist production, sectoral disproportions, underconsumption and realization problems, labor-shortage and population pressures, credit insufficiency, excess capital, state policy, productivity and wages squeezing profits.[57]

According to Professor Costas Lapavitsas, "both Hilferding and Lenin – indeed most of the leading Marxists of their time – treated crises as complex and multifaceted phenomena that could not be reduced to a simple theory of the rate of profit to fall. The notion that the normal state of capitalist production is to malfunction due to a persistently excessive organic composition of capital, or even due to falling 'surplus' absorption, would have been alien to classical Marxists."[58] Implicitly or explicitly, it was argued by these Marxist economists that economic crises, although they are a fairly regular occurrence in the last two centuries of capitalist development, do not all have exactly the same causes. There are all sorts of things that can go wrong with capitalism, throwing the markets out of kilter.[59]

Howard & King claim that the TRPF was mostly "neglected" in Marxist theoretical discussions during the 1920s.[60] Callinicos & Choonera claim that the TRPF actually played a "marginal" role in much of the whole history of Marxist economics, even although it was the truly revolutionary core of Marx's teaching.[61] During the British general strike of 1926, for example, there was no evidence of English discussion about the TRPF.

In the non-English Marxist literature, however, the TRPF did get plenty of attention, except that the TRPF was never seen as the "be all and end all" of crisis theory. For the continental thinkers, the trend in profitability was linked with many different economic variables and circumstances.[62] The issue then was about the real interconnection of all these variables together (the Totalité or Zusammenhang), and not simply about whether the profit rate was up or down.

When Henryk Grossman published his famous 1929 breakdown theory, he intended to correct faults in the 1920s theoretical debates about the dynamics of capitalist growth - as discussed in the writings of Karl Marx, Nikolai Bukharin, Otto Bauer, Rosa Luxemburg, Fritz Sternberg and many others. "Unlike Marx's diagrams, Bauer's diagram includes the rising organic composition of capital, a falling rate of profit, a rising mass of profit, and the faster development of Department I – the department that produces the means of production – relative to Department II – the branch that produces the means of personal consumption."[63]

Mono's vs. multi's

Some Marxists sought the cause of capitalist crises in only one specific factor as the "root of the evil", e.g. over-accumulation, underconsumption, the anarchy of production, population pressures, class conflict, falling profits, state policy etc. Others tried to integrate different contributing causes in one theory. In modern Marxism, some mono-causal Marxist theorists (the "mono's") still attribute crises to one single factor (principally, the TRPF).[64] Others (the "multi's") have argued for a multi-causal approach in which a distinction is drawn between the "triggers" of the crisis, its deeper underlying causes, and the concrete manifestation of crises.[65]

Transformation problem

The Marxian controversy about the so-called transformation problem began in earnest after the publication of Friedrich Engels's 1894 preface and 1895 supplement to his edition of Marx's third volume of Capital.[66] In Capital, Volume III, Marx dropped his simplifying assumption that commodities are sold at their value, in favour of a theory of competitive market prices, regulated by production prices which diverged from product-values (the so-called "transformation of commodity values into prices of production"). Yet he supplied no convincing proof or evidence, that production prices were themselves shaped and determined by product-values.

Allegedly Marx failed to prove, how the leveling out of different rates of profit through competition toward a general, average profit rate could be logically reconciled with the determination of product-values by labour-time. Marx assumed in his simple numerical examples, that the aggregate profit volume was allocated to production capitals according to a uniform profit rate, but that assumption happened to run into conflict with other assumptions in his theory. If the inconsistency could not be resolved, then the validity of a labour theory of product-values as such was put into question. Five scholarly positions emerged subsequently in the West:[67]

- Marx's transformation problem is a real and unsolvable problem (e.g. Ian Steedman).

- It is a real but solvable problem (e.g. Gérard Duménil).

- A pseudo-problem was created, through false interpretations of Marx, which gets in the way of consistently developing Marx's idea (e.g. Andrew Kliman).

- There is no transformation problem, and there never was one, if Marx is simply understood literally, in his own terms (e.g. Fred Moseley).

- There is a transformation problem (Marx did overlook some quantitative implications), but econometrically it is not very significant compared to the overall close fit between the classical theory of value and the economic data (e.g. Anwar Shaikh). The controversy about the problem was vastly bigger, than the size of the problem warranted. The mathematical insight here is, that all classical theories of value – whether Smithian, Ricardian, Millsian, Marxian or Sraffian etc. – necessarily involve a transformation problem, since they all assume that the prices for products diverge from, and oscillate around, some underlying production value or "natural" price, while profits proportional to capital size, and unequal capital compositions in different enterprises and sectors, are being assumed at the same time.

Those socialist economists who thought that the transformation problem was a real but unsolvable problem, usually abandoned Marx's value theory, as well as his theory of the TRPF. With the other four interpretations, economists might or might not reject Marx's TRPF theory. There might also be some overlap in the five positions (e.g. when scholars thought there were both pseudo-issues and some real problems). Marxists often disagree among themselves about what the transformation problem is about, and what its implications are.

Classical debate

Engels realized very well, that there were unsolved issues in Marx's theory of value and capital, and he had previously invited other economists to help solve them.[68][69] Already before Capital, Volume III was first published, Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky, German socialists like Conrad Schmidt and various Italian authors were critically assessing the implications of Marx's theory.[70] But Engels himself died in 1895.

Subsequently, Eugen Böhm von Bawerk[71] and his critic Ladislaus Bortkiewicz[72] (himself influenced by Vladimir Karpovich Dmitriev[73]) claimed that Marx's argument about the distribution of profits from newly produced surplus value is mathematically faulty.[74] This gave rise to a lengthy academic controversy.[75][76][77][78][79][80] Critics claimed that Marx failed to reconcile the law of value with the reality of the distribution of capital and profits, a problem that had already preoccupied David Ricardo – who himself inherited the problem from Adam Smith, yet failed to solve it.[81]

Marx was already aware of this theoretical problem when he wrote The Poverty of Philosophy (1847).[82] It gets a mention again in the Grundrisse (1858).[83] At the end of chapter 1 of his A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), he referred to it, and announced his intention to solve it.[84] In Theories of Surplus Value (1862-1863), he discusses the problem very clearly.[85] His first attempt at a solution occurs in a letter to Engels, dated 2 August 1862.[86] In Capital, Volume I (1867)[87] he noted that "many intermediate terms" were still needed in his progressing narrative, to arrive at the answer. Engels suggested, that Marx had indeed solved the problem in the posthumously published Capital, Volume III, but critics alleged Marx never delivered a credible or definitive solution.

Specifically, critics claimed that Marx failed to prove that average labour requirements are the real regulator of product-prices within capitalist production, since Marx failed to demonstrate what exactly the causal or quantitative connection was between the two. As a corollary, Marx's theory of the TRPF was undermined as well, since it was based on a necessary long-term evolution of value-proportions between the composition of production capital and the yield of production capital.

Ricardianism

According to the classical Ricardian economists, solving the transformation problem was an essential prerequisite for a credible theory of prices – a theory that would genuinely explain the relationship between the different variables determining prices, and the effects of changes in those variables. The theory of economic value was the foundation for the theory of prices, because prices could not be understood and explained without assumptions about economic value. Somehow, the labour theory of the substance of product-value had to be reconciled with observed patterns in the distribution of profits and prices. Hence, a version of the transformation problem already existed in Ricardian economics, before it existed in Marxian economics, and, according to Marx, Ricardo's inability to solve it, directly contributed to the break-up of the Ricardian school, and to the demise of the labour theory of value.[88]

Marx's claim all along was, that Smith and Ricardo could not solve the problem, because they fudged the correct definition of very basic concepts and categories in political economy. Marx implied, that if things were correctly conceptualized, then the pieces of the puzzle could be fitted together in a logically sound way. The subsequent debate then centered on whether Marx had really solved a fundamental problem of the classical labour theory of value which Ricardian economics had failed to solve, so far, or whether there was an alternative (Ricardian) solution preferable to Marx's. Prof. Anwar Shaikh states that, among economists, this issue divided supporters of the labor theory of product-value for more than one century.[89]

What made the 20th century debate especially complicated and confusing, was that Ricardo's theory and Marx's theory were often mixed up with each other. It was often unclear or controversial, what the exact differences between them were, and how that mattered. In criticizing and reworking Ricardian theory, Marx had kept some of its ideas, but also altered the whole theoretical frame of reference, creating a new social and economic ontology.[90] Some Marxian professors, like Makoto Itoh, Michael Heinrich, Ernesto Screpanti, Tony Smith and Chris Arthur, aim to re-edit Marx's dialectical transformation argument, in order to cleanse it from all "Ricardian residues" – the suggestion being, that Marx himself had never completely freed himself from Ricardian concepts in the economic manuscripts which he did not publish himself.[91][92][93][94][95]

Wassily Leontief and Paul Sweezy

The German transformation controversy, insofar as it concerned the reproduction of capital, helped to inspire Wassily Leontief's matrix system[96] of input–output economics[97][98][99][100] which later made it possible to obtain measures of the Marxian rate of profit (see below). In Berlin, Ladislaus Bortkiewicz co-supervised the young Leontief's doctoral studies together with Werner Sombart.[101][102]

Leontief's father, a professor in economics, studied Marxism and did a Phd on the condition of the working class in Russia.[103] Leontief himself studied Marxism as undergraduate, but claimed later that he had been interested in Marx only as a "classical economist"; he took a dim view of Marx's mathematical ability and of the labour theory of value.[104] Leontief was primarily interested in applied economics and testable hypotheses. His personal experience as a student with Cheka persecution made Leontief wary of Marxism, whatever his appreciation of Marx.

The transformation problem nevertheless remained a relatively obscure academic dispute, until Paul Sweezy drew attention to it in his widely read 1942 book The Theory of Capitalist Development.[105][106] The Bortkiewicz-Sweezy interpretation of Marx was very influential in the second half of the 20th century, in Marxist, neo-Ricardian and Post-Keynesian circles.[107] From the 1970s, the academic debate broadened to the more general issue of what exactly is the relationship between values and prices, and how that should be conceptualized.[108][109][110]

Marx's theory

In Capital, Volume I, Marx analyzed how the capitalist enterprise buys materials and labour-power (inputs) to produce commodities sold for profit (outputs). At that stage he was not concerned much with price fluctuations or market volatility (except for the price of labour hired). In chapter 9 of Capital, Volume III, he notes that he had previously assumed that, to the purchasing capitalist, the value of a commodity bought was the same as its cost-price.[111] In reality, he argued, this cost-price is itself a market price based on a production price (a cost-price + a profit) of the supplying capitalist producer: the input purchasing price of one capitalist is the output selling price of another capitalist. So the acquisition cost-price of inputs itself corresponded to both a value and a surplus value, and the market prices of inputs might diverge from the labor-value of inputs. Hence, said Marx, if the cost-price of a newly produced output is assumed to be equal to the labor-value of the inputs used up in producing it, "it is always possible to go wrong"[112] in the calculation of the output production price (because input acquisition prices and input labor-values could diverge, given that the inputs could be bought above or below their value, and given that after purchase their inventory value could change, during the production process[113]).

In drafting a simple model of profit distributions, Marx straightforwardly equated – for the sake of argument – the total cost-price of society's new gross output with the total production capital advanced to produce it, abstracting from many intervening variables such as capital depreciation and turnovers.[114] Marx furthermore assumed, that at the point where a new output had been produced, its cost-price in the bookkeeping (a sum of money-capital representing materials costs, wage costs and operating costs) was a given, unchangeable datum,[112] and he considered that price-value discrepancies of inputs bought were irrelevant to his analysis, since it was the value of this new output (and not the capital advanced) that was being related to a general price level and a general profitability level in the markets where the output was sold.

The cost-price of the new output was not based on a hypothetical "labor-value" of inputs, but based on what the producers actually paid for the inputs that were used up to create their outputs. Using various inputs, a new output was produced. This new output had a value, but precisely how much of that value would be realized as revenue, was difficult to know in advance. The difference between the selling price and the cost price of the new output sold, was the surplus value realized as profit by the producer of that output, and the argument was, that this profit would normally (assuming ordinary competition) tend to gravitate to an amount reflecting the average profit rate on capital. The question was about how the profit volume included in the total value product would be distributed among the producing enterprises.

If businesses could not reach a baseline profitability, they would be driven out of business sooner or later, or they would be taken over by another business and restructured, so that they did become sufficiently profitable. Inversely, if businesses overcharged for their commodities to obtain more profit, fewer people would buy them, and they would suffer decline as well. So output could normally be sold only within a fairly narrow range of prices, acceptable to both buyers and sellers. Marx then examined what the division of the total newly produced surplus value would be, among producing enterprises with varying capital compositions, on the hypothetical assumption of a uniform profit rate established by free competition.[115]

Under Marxism–Leninism and Sraffianism, the "uniform rate of profits" was often taken as the literal truth.[116] Marx himself knew very well though that a uniform profit rate (a "general profit rate", e.g. a 10% net profit on all production capital) did not truly exist in the real world, except as a tendency in the competitive process, as a norm for acceptable returns, or as a statistical average.[117] If it is accepted that "perfect competition" does not exist in the real world, then a "uniform rate of profit" also cannot exist in the real world – both are just idealizations used to understand some implications of a model.

Marx wanted to examine the share-out of newly produced surplus value in its simplest and purest forms, abstracting from all kinds of variability of circumstances that would make his own calculation extraordinarily complex (see further prices of production). The formation of a normal rate of profit on capital invested, common to most producers, defined the basic parameters of competition, and thereby it defined the main developmental dynamic of the capitalist production system.[118]

Ladislaus Bortkiewicz

The theoretical problem that nevertheless remained in Marx's story, according to Ladislaus Bortkiewicz and other Ricardian theorists like Mühlpfordt, Dmitriev and Charasoff,[119][120][121] was how the input and output results of interacting sectors of industry could be modeled in aggregate, so that total product values and total production prices would exactly match up in aggregate, and so that the price-value divergences at the micro-level would all cancel out at the macro-level.[122]

For Bortkiewicz, this redistribution was a purely mathematical problem, a matter of correct formalization. The equality of total production prices and total values (Bortkiewicz talks about "price units" and "value units", with a "system of prices", and a "system of values"[123]) could be understood to mean, that they were both equal to a given quantity of gold, or a given quantity of labor hours, or a given quantity of an assumed standard commodity (where value = price).[124][125] A perfectly consolidated result was required, as a proof that production prices represented merely and only a quantitative redistribution of product-values.

In turn, that Marxian quantitative proof would, in Bortkiewicz's interpretation, confirm logically that there was a determinate relationship between product-values and product-prices, since every value quantity would always map to a price quantity and, in aggregate, every positive price-value deviation would always be balanced out exactly by a proportional negative price-value deviation. Marx's system of categories for describing the accumulation of capital from production, and his theory of the levelling out of differences in rates of profit, would be validated as logically sound, and as meeting a standard of scientific rigour.

The relevant point here was, that price-value divergences occurred both with regard to inputs to production and with regard to outputs; but Marx himself had ignored the input price-value divergences in his simple quantitative illustrations of the distribution of profit.[126] Since outputs become inputs and inputs become outputs, critics alleged that unless input values are transformed in the calculation as well, the absurd mathematical effect in the model is, that capitalist producers selling a good obtain a sale price that differs from the price paid by capitalist producers buying the same good.[127]

Five ideas

In a static three-sector model, it proved mathematically difficult to join up five ideas. These five ideas were:

- 1. All production capitals attract the same profit rates, so that profits are distributed in proportion to the size of the capitals (the so-called "uniform profits" assumption).

- 2. Production units or sectors each have a different organic composition of capital.

- 3. The sum of production prices is equal to the sum of product values.

- 4. The total profit-money distributed to production units is equal to the total surplus value produced.

- 5. The rate of profit in price terms, is equal to the rate of profit in value terms.

The input-output equations could be made to work, only if additional assumptions were made.[128] But even in a dynamic model, it can be shown mathematically that assumptions (1), (3) and (4) have a crippling effect on the plausibility of longterm quantitative results obtained with the model. However, what ought to be concluded from this modelling exercise, still remains very much in dispute (is the theory wrong, are the concepts and assumptions wrong, is the interpretation of the concepts wrong, is there a big difference between the model and the real world, etc.).

The algebra of the classical transformation problem is rather simple;[129] the real difficulty is about whether the economic relationships involved are adequately conceptualized, and how we could know that. Both Marx[130] and von Bortkiewicz[131] actually admitted or implied themselves that assumptions (1), (3), (4) and (5) cannot be true in the real world, but this was never recognized in the 20th century literature. It casts doubt on the importance or relevance of the classical transformation problem (in particular because it largely disregards the social ontology of values and prices, as well as the techniques to measure product-values in the real world).

In 1950, Cambridge economist Joan Robinson dismissed the transformation problem as "just a toy", arguing that "the whole argument is condemned to circularity from birth, because the values which have to be 'transformed into prices' are arrived at in the first instance by transforming prices into values."[132]

Redundancy of value

Bortkiewicz's analysis nevertheless raised the very important question of what the point of Marx's value theory is. Is there any real difference between Marx's "values" and theoretical prices?[133] If there is no real difference, neo-Ricardians argued, then Marx's value theory is redundant; one could then just as well make all the same sorts of arguments in price terms.[134] In Sraffa's alternative theory, production prices can be calculated straightforwardly from physical quantities, the technical coefficients of production and the real wage, without any reference to the labour-value of inputs and outputs.[135]

The advantage of this approach seemed to be, that:

- There exists no "transformation problem" of converting values into prices through a quantitative adjustment anymore.

- The whole awkward issue of the exploitation of labour is circumvented.

- Value theory can be replaced with equilibrium theory to explain prices, since "value" then simply stood for "equilibrium prices" (such as the Smithian or Ricardian "natural prices").

- A system of equilibrium prices could be formulated for the critical variables involved in production, to explain price relationships.

At the same time, Marx's theory of the formation of a general rate of profit, and his theory of the TRPF, would no longer be valid. This trend of thought is exactly what happened in leftwing economics, during the second half of the 20th century (see below), although a minority of Marxists – inspired by Isaak Illich Rubin and Roman Rosdolsky – continued to defend Marx's theory of the forms of value (somewhat confusingly, however, many value-form theorists[136] also reject Marx's own value theory, or modify it according to their own taste).

In classical Ricardian economics, the theory of economic value still played an important role, but in neo-Ricardian economics there exists only a theory of prices; the role of "value" is reduced to that of an aggregation principle for price magnitudes, but value not a real determinant of the rate of profit.[137]

Value theory as add-on

However, there are also Marxists who think that value-theory is still a useful "add-on" to ordinary neo-Ricardian or post-Keynesian price theory, because value-theory penetrates through the "appearances" of commodity fetishism to the "essence" of exploitation as the source of profit.[138] According to this interpretation, price-relationships express the observable (but deceptive) surface appearance of what happens in the economy,[139] while value relationships express the unobservable essence of what happens.[140] Rob Bryer stated that "The majority of Marxists today argue defensively that [Marx] did not intend [his theory of value] to explain prices and rate of return on capital, but gave us only a qualitative theory of capitalist exploitation".[141] Paul Burkett for example claims that "Marx’s primary purpose in Capital ... was not to theorize market prices, but to dig beneath market appearances 'to reveal the economic law of motion of modern society".[142]

In this interpretation,[143] there is no necessary connection between price-relationships and value-relationships, quantitative or otherwise, because the value theory models and the price theory models exist at qualitatively different levels of abstraction (although, in principle, both refer to the same reality). It then follows quite logically, that value theory cannot offer any substantive explanation of price movements (including empirical profits), whether in theory or in reality[144] and that price theory is a completely separate area of concern.

Five main objections are made to the "add-on" approach.

Metaphysics

With the add-on approach, the theory of value as such becomes an untestable, metaphysical[145] theory: value is a mysterious, hidden entity, that can never be observed in any way, let alone measured, only intuited by pure theory among academic Marxist initiates (or divined by the Central Committee[146]).

Marx himself stated in his manuscript that his analysis of the configurations of capital aimed to "approach step by step the form in which they appear on the surface of society... in competition, and in the everyday consciousness of the agents of production themselves".[147] Evidently Marx then did intend to show the connections of labour-values with the observable price relationships, although he did not write a detailed analysis of the competition process himself. This task was only taken up later by Marxian economists (including Samezō Kuruma, Anwar Shaikh, Willi Semmler and Lefteris Tsoulfidis).[148][149][150][151][152][153]

If, as Marx argued in Capital, Volume III, pricing and product-values influence each other, through successive adjustments, his value theory in fact makes no sense at all without reference to prices. It would be like saying, that to understand the economic value of a commodity, its price can be disregarded. Marx claimed no such thing – he merely started off by assuming, for argument's sake, that the price and value of commodities produced were the same. This initial simplifying assumption seemed reasonable enough, since competition would constrain the margins of value/price deviations for the distribution of most commodities – the deviations would ordinarily not be very large (ordinarily, vastly overvalued or undervalued goods could not be sold in a competitive market). Econometric research done from the 1980s onward suggests that this is true.[154]

Eclecticism

An integral, consistent economic theory becomes impossible with the add-on approach,[155] since market prices, product-values and social relations are always in different baskets. This theoretical eclecticism results in low explanatory power, and low predictive power – there exist multiple different theories and concepts at once, which all can interrelate/combine in all kinds of possible and ad hoc configurations, like a kaleidoscope, and therefore "explain" and "predict" everything and nothing.

When the results of the eclectic analysis appear implausible, the kaleidoscope is twisted slightly, to highlight the perfect geometry of yet another (though similar) "pattern". It means, that there is no clear idea about what the anomalies facing the theories should be attributed to (because they could be all kinds of things), and that no firm conclusions can be drawn from experience (all that happens, is that one theoretical preference is replaced with another flavour, that jells better with the concerns of the day).

Essences

The add-on approach misunderstands Marx's concepts of value, value-form and price-form, and falsifies the meaning of Marx's distinction between "essence" and "appearance".

According to Marx himself, the "essence" is not some kind of esoteric, mystical "unobservable" kernel. Indeed, he says himself that the essence of the matter is "comprehensible to the popular mind" ["der ordinären Vorstellung geläufig sind"[156]] – it is just that the "real interconnection" of phenomena, the "real story" about how it works, is usually clouded by all kinds of peripheral aspects, irrelevancies, biases, one-sided representations, and distractions. Market phenomena can appear other than they are, and their real significance may not be immediately obvious (beyond occasional glimpses, the essence of the matter becomes perfectly clear, only at particular "crunch" moments, or when the researcher has actually done the real work to dig it out, and put it in context).[157][158][159]

If there existed a "world of essences" which were never observable in any way, and always "hidden", it would be impossible to do any science, to find out what the essences are. It would be impossible to get at any essence, ever – analogous to a court of justice which examined case after case, but could never reach any certainty at all about whether any crime was committed or not. That is obviously not what Marx argues. Hegel never argued that either; Hegel's philosophical "doctrine of the essence" is not at all about "esoteric, mysterious hidden mechanisms". Instead, it explains in detail, how "first, essence shines within itself, or is reflection; second, it appears; third, it reveals itself."[160]

Unobservables

The observable/unobservable distinction being drawn by the add-on approach is simply false – while some prices are observable, others are not (since they are inferred or derived magnitudes, or purely theoretical idealizations), and some prices are a mixture of both actual and assumed magnitudes (combining observations and extrapolations in the same calculation). The naive concept of prices as an "observable surface phenomenon" fails utterly once we understand more about what prices mean (see value-form and real prices and ideal prices).

Unfortunately, Marxist philosophers speculatively invented a "secret world" of "hidden causal mechanisms" beyond "surface appearances", instead of investigating the real world, to understand what the "mechanisms" actually are.[161] In the absence of verification, theorizing spins off in all kinds of directions without any attempt at proofs – because it lacks an empirical, objective explanandum, it becomes unclear what the explanatory purpose of theorizing activity actually is. It could be just a theory about theories, or theory for the sake of theory.

The result is either a postmodern skepticism/timidity about the possibility to know anything, a conspiracy theory, or else an arrogant faith in the power of pure theory to divine the truth about society, through transcendental intuition (without thorough study of the relevant facts).[162] None of these approaches is particularly helpful for scientific research.

Abstractionism

Talk about "levels of abstraction" by the add-on crowd[163] is vacuous, unless the exact limits of application of the abstractions can be specified clearly. Without such specification, nothing can be tested or substantively contested (logically or empirically).[164] It just remains loose philosophical talk, sophistry or petitio principii, uncommitted to any particular consequence.

Theorizing about capital and labour, Marx certainly engaged in abstraction, but not willy-nilly in some speculative sense. Instead, he critically sifted through what political economists, businessmen, statesmen, factory inspectors, journalists and workers had actually said and done, to develop a new theory that would be rigorous, consistent and durable.[165] He did not make any great claims to originality,[166] and carefully footnoted "who said it first". The theory ended up going far beyond immediate experience, but it was rooted in the stubborn facts of experience, and returned to those facts all the time. It had to explain the observable facts, and also explain why their meaning was construed in specific ways. That was Marx's "science".[167] If Marxists want to cling sentimentally to "value theory" regardless of facts and logic, this cannot be called a "science" - it has more in common with a new age religion.[168]

Okishio's theorem

The Japanese economist Nobuo Okishio famously argued in 1961, "if the newly introduced technique satisfies the cost criterion [i.e. if it reduces unit costs, given current prices] and the rate of real wage remains constant", then the rate of profit must increase.[169]

Assuming constant real wages, technical change would lower the production cost per unit, thereby raising the innovator's rate of profit. The price of output would fall, and this would cause the other capitalists' costs to fall also. The new (equilibrium) rate of profit would therefore have to rise. By implication, the rate of profit could in that case only fall, if real wages rose in response to higher productivity, squeezing profits.

This theory is sometimes called neo-Ricardian, because David Ricardo also claimed that a fall in the average rate of profit could ordinarily be brought about only by rising wages (one other scenario could be, that foreign competition would drive down the local market prices for outputs, causing falling profits).

At first sight, Okishio's argument makes sense. After all, why would capitalists invest in more efficient production on a larger scale, unless they thought their profits would increase? Orthodox Marxists have responded to this argument in various different ways.[170]

Criticism

The absence of fixed capital in Okishio's model is rather crucial, because:

- fixed capital is usually the largest part of the physical capital outlay.

- lowering unit costs long-term typically requires additional fixed investment.

- the increase in productivity which new fixed capital makes possible, typically goes along with wage rises.

- it is primarily the growth of fixed capital which, in Marx's theory, lowers the profit rate in the long term.

John E. Roemer therefore modified Okishio's model, to include the effect of fixed capital. He concluded though that:

"... there is no hope for producing a falling rate of profit theory in a competitive, equilibrium environment with a constant real wage... this does not mean... that there cannot exist a theory of a falling rate of profit in capitalist economies. One must, however, relax some of the assumptions of the stark models discussed here, to achieve such a falling rate of profit theory."[171]

It is also possible to construct an alternative Okishio-type model, in which the rising cost of land rents (or property rents) lowers the industrial rate of profit.[172]

Cycle or long run

One dispute which has never been finally resolved is whether the TRPF should be interpreted as a cyclical tendency, or as a secular long run trend.[173] Geert Reuten from the University of Amsterdam has argued that there is evidence that Marx originally believed in a long run secular tendency, but that, later on, he changed his position to a cyclical tendency.[174][175] In contrast to this view, Anwar Shaikh from the New School in New York City argued that Marx meant the TRPF as a secular long run trend; a cyclical tendency and a long-run tendency could also be combined in one theory, where a series of cycles shows a gradual fall in the average rate of profit, although there is an upturn in each cycle.[176]

Following Michael Heinrich,[41] David Harvey criticized Engels's editing of Capital, Volume III, and emphasized in a conference text that Engels himself inserted the sentence "In practice, however, the rate of profit will fall in the long run, as we have already seen."[177] The suggestion is, that in the text preceding Engels's inserted sentence, Marx himself had never said anything about such a long-run falling tendency.

Harvey's view contrasts with Marx's preceding text, in which Marx says that as the capitalist mode of production advances, its general rate of profit must steadily decline, "since the mass of living labour applied continuously declines in relation to the mass of objectified labor [i.e. means of production] that it sets in motion."[178] However, Michael Heinrich argues that Marx in his old age paid no attention anymore to the falling tendency, suggesting it was no longer important to him.[179]

First empirical tests

In the 1870s, Marx certainly wanted to test his theory of economic crises and profit-making econometrically,[180] but adequate macroeconomic statistical data and mathematical tools did not exist to do so.[181] Such scientific resources began to exist only half a century later.[182]

In 1894, Friedrich Engels did mention the research of the émigré socialist Georg Christian Stiebeling, who compared profit, income, capital and output data in the U.S. census reports of 1870 and 1880, but Engels claimed that Stiebeling explained the results "in a completely false way" (Stiebeling's defence against Engels's criticism included two open letters submitted to the New Yorker Volkszeitung and Die Neue Zeit).[183] Stiebeling's analysis represented "almost certainly the first systematic use of statistical sources in Marxian value theory."[184]

Although Eugen Varga[185][186] and the young Charles Bettelheim;[187][188] already studied the topic, and Josef Steindl began to tackle the problem in his 1952 book,[189] the first major empirical analysis of long-term trends in profitability inspired by Marx was a 1957 study by Joseph Gillman.[190] This study, reviewed by Ronald L. Meek and H. D. Dickinson,[191] was extensively criticized by Shane Mage in 1963.[192] Mage's work provided the first sophisticated disaggregate analysis of official national accounts data performed by a Marxist scholar.

Long waves

Starting off with pioneering work by Ernest Mandel from 1964,[193] various attempts have been made to link the long waves of capitalist development to long-term fluctuations in average profitability.[194][195][196] By "long waves" Mandel did not mean "long cycles".[197][198]

Mandel vs. Grossman

Mandel's influential Phd thesis Late Capitalism (in German 1972, English version 1975) was a critical response to Henryk Grossman's theory. Like Henryk Grossman, Mandel was convinced of the centrality of profitability in the trajectory of capitalist development, but Mandel (following Rosdolsky's critique of Rosa Luxemburg's theory[199]) did not believe that Marx's reproduction models could be used to create a theory of capitalist crises.[200]

In Grossman's profitability model, there was only a series of business cycles and, sometime after the 34th cycle, a general breakdown of capitalism, because insufficient surplus value was being generated.[201][202][203] Leaving aside the issue of the validity of Grossman's model, his picture of capitalist development did not explain historical phases of faster and slower economic growth lasting about 25 years or so. After World War 2, a long boom occurred, instead of a deepening capitalist crisis which many Marxists had expected.[204] That was what Mandel wanted to explain[205] (Mandel's and Grossman's growth models both ignore the accumulation of non-productive capital assets and profits not arising from new surplus-value).

Rowthorn vs. Mandel

Mandel's interpretation was strongly criticized by Robert Rowthorn.[206] Although Mandel's profit theory was enormously more complex than Grossman's profit theory, this complexity itself became problematic: there were so many interacting "semi-autonomous variables" in Mandel's theory, that observable empirical trends could be attributed to any number of interacting variables; this meant that no particular result necessarily followed from the theory, and that the explanans (that which explains) became confused with the explanandum (that which has to be explained).[207]

Thus, "It is never clear, for example, whether Mandel considers capitalism has an inherent tendency toward overproduction which periodically expresses itself in a falling rate of profit, or whether overproduction itself is caused by a falling rate of profit."[208]

Mandel replied to such criticisms in his 1978 essay "Marxism and the crisis", where he argued this dichotomy does not make sense, because it is based on a false social ontology.[209] Overproduction and overaccumulation[210] were, he argued, inseparable phenomena, and surplus value could not be realized as profit income unless output was sold; consequently the average rate of profit and the rate of market expansion mutually determined each other.

Shaikh vs. Mandel

Anwar Shaikh argued that Mandel got it wrong, because Mandel saw "evidence of a rise-and-fall in the actual rate of profit causing the long upturn and downturn".[211] According to Shaikh, Mandel's interpretation mixed up the rate of profit with the mass of profit, and ignored the impact of changes in capacity utilization on the rate of profit. Instead, Shaikh argued that "...in Marx's theory of the falling rate of profit, the transition between long-wave phases is correlated with the movements of mass of profit, and not with that of the rate of profit (as in Mandel)".[212] Mandel replied, that Shaikh's own data series showed that an upturn in the average rate of profit occurred at the start of the long boom, in addition to the fall in the average rate of profit toward the end of the boom.[213]

Profits and crises I

Mandel maintained that falling profits were only one factor in the recurrent sequence from boom to slump. Being a Marxist socialist, he argued that the basic reason why capitalist crises occurred is that capitalism is a system of production run by competing producers, based on private property.[214] In this system, "what is rational from the standpoint of the system as a whole is not rational from the standpoint of each great firm taken separately, and vice versa."[215] According to Mandel, that also explained why bourgeois macroeconomics and microeconomics contained quite different principles and concepts of economic behaviour (in contrast to Marx's economics, where macro and micro share the same concepts).[216]

Thus, in every branch of economic activity, capitalist business could never escape from recurrent problems of overinvestment and underinvestment, which periodically culminated in general crises.[217] Following György Lukács, Mandel portrays capitalist rationality as a "contradictory combination of partial rationality and overall irrationality."[218] It is not that competing businessmen are "irrational", far from it, but that their own "instrumental rationality" and "value rationality" (in a Weberian sense) differ from the functional logic of capitalism as a market system, and, therefore, the two run into serious conflicts at times – leading to crises. Simply put, markets and government policy can work in your favour, but they can also work against you. In a private enterprise system based on competition, when things get to the crunch, it becomes impossible to reconcile self-interest with the general interest, even with mediation by the state. Then there are winners and losers, on a very large scale. During the boom, most people can make some gains, even if the gains are unequal. In a real crisis, the gains of some are at the expense of others - competition intensifies, and often becomes brutal.

In a 1985 article, reprinted as an appendix in the last French edition of Late Capitalism, Mandel tried to defend his interpretation against accusations of vulgar eclecticism.[219] His final view was that "...under capitalism, the fluctuations of the average rate of profit are in a sense the seismograph of what happens in the system as a whole... that formula just refers back to the sum-total of partially independent variables, whose interplay causes the fluctuations of the average rate of profit".[220] The analytical challenge was to verify this interplay empirically, to understand why the long-term ups and downs in the average profit rate occurred.

Underproduction

In the modern epoch of financialization, the main criticism of Mandel's idea is that over-accumulation can combine with underproduction, if it is safer (or more profitable) to invest in solidly insured non-productive assets (financial assets, stockpiles and real estate).[221] Thus, much less is actually produced than could be produced.

Martin Wolf stated: "the world economy has been generating more savings than businesses wish to use, even at very low interest rates."[222] Joseph Stiglitz similarly argued that from the 1990s onward, banks lent more and more money to investors who mainly did not use it to create new business producing things, but to speculate in already existing assets for capital gain, thereby pushing up asset and property prices.[223]

The general claim made here is that, in the real world (and outside bourgeois propaganda rhetorics), modern Western-style capitalism is not anything like a "risk-taking" capitalism. It is more like a political economy of insurance capitalism, where state insurance, the private insurance industry, the hedging industry, the funds management industry and the burgeoning derivatives markets rake in trillions of dollars per year, just to protect people and assets against all significant risks and losses.[224] Bourgeois sociologists like Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens began to refer to the concept of the risk society in a deregulated investor capitalism,[225] where there is big money in talking about risks.[226] The nervous anxiety about risk, critics argue, vastly exceeded the actual risks.

In the underproduction critique, the only real "risk-takers" left in the brave new Western world of "risk-free accumulation" are (1) the workers, peasants and poor people who have to do long hours of hard, hazardous and/or dirty work for a living, for a low wage, often with meagre or non-existent pensions, insurance[227] and healthcare, (2) sundry people who reject or fall outside the rules of the insurance system, or who are connected with criminality, (3) people who do adventure sports and the like.

Although the global insurance apparatus has grown huge, so far there exists no general Marxian theory of risk insurance and its effect on the average rate of profit. It is obvious though, that if one can insure capital against losses at a fairly small cost, the gains may outweigh the costs considerably, raising business certainty, market confidence and profit yields across time – a likely reason why the volume of derivative contracts has continued to grow strongly.[228] However, this point has been disputed after the 2007–2009 financial crash, since the very financial products that were intended to secure capital and profits, ended up creating more insecurity for the global majority (food, housing, jobs, incomes, savings and pensions).[229]

Secular trend

In defense of the theory that the organic composition of capital does rise in the long term (lowering the average rate of profit), Mandel claimed that there does not exist any branch of industry where wages are a growing proportion of total production costs, as a secular trend. The real trend is the other way: toward semi-automation and full automation which lowers total labor costs in the total capital outlay.[230]

Critics of that idea point to low-wage countries like China, where the long run trend is for average real wages to rise. For example, the Chinese Communist Party aims to double Chinese workers' wages by 2020.[231] Zhang Yu and Zhao Feng provide some relevant data.[232] Minqi Li has compared average profit rates for China, Japan and the USA.[233] Dr. Bin Yu, a member of the Academy of Marxism at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (the highest scientific authority on Marxism in China), affirms that the TRPF theory is correct, and that the data prove it.[234] Hao Qi found that profitability in the PRC fell after 2008.[235]

Monopoly profits

Rosa Luxemburg already stated in her 1899 pamphlet Social Reform or Revolution? that:

“Cartels are fundamentally nothing else than a means resorted to by the capitalist mode of production for the purpose of holding back the fatal fall of the rate of profit in certain branches of production”.[236]

In the course of the 20th century, this idea became widely accepted among Marxists - it was taken over e.g. by Nikolai Bukharin, Rudolf Hilferding and Henryk Grossman. For example, Grossman wrote in his Breakdown book that:

"A world monopoly in raw materials means that more surplus value can be pumped out of the world market".[237]

Inspired by Josef Steindl and Baran's earlier work, Paul Baran and Paul Sweezy postulated in their 1966 work Monopoly Capital that there existed a "law of increasing surplus" which counteracted the TRPF within a capitalism that had fundamentally changed.[238][239] Just after the book was published, the average industrial rate of profit in most advanced capitalist countries began to fall, and continued to fall substantially for about 5–7 years.[240]

The official orthodox Marxist–Leninist theory of state monopoly capitalism ("stamocap")[241] similarly suggested that in the 20th century epoch of the "general crisis of capitalism", the state, its public funds and imperialist exploitation acted as the guarantor and promoter of stable monopoly profits by corporations – counteracting the TRPF.[242][243] The general thrust of monopoly theories is that profitability does not fall, because the ordinary laws of capitalist market competition are overruled by (1) state intervention, (2) corporate monopolization of resources and markets, and (3) colonial superprofits.[244]

However, Ben Fine and Laurence Harris combined the TRPF with state monopoly capitalism theory at a higher level of abstraction: "[The TRPF] is not a law which predicts actual falls in the rate of profit (in value or price terms)".[245] At an even higher level of abstraction, Michael A.Lebowitz postulated "the inner tendency of Capital to become one".[246] Anwar Shaikh however recently made the case that monopoly capital has never truly existed, since normally speaking business cannot totally monopolize a market, or evade competition altogether; as a logical corollary, business cannot evade the TRPF. Shaikh rejects the idea that bigger enterprises necessarily have higher profit rates than smaller ones.[247]

Also inspired by Josef Steindl's analysis, Ernest Mandel argued (after Rudolf Hilferding[248]) that if corporations monopolizing product markets can evade price competition to a considerable extent, they can also evade the general tendency for differences in profit rates to level out through competition (in the direction of an average rate).[249] Even if monopoly profit rates fell, they would usually remain higher than the profit rates of small and medium-sized firms.[250] The monopolists could raise their prices only within certain limits, beyond which they would attract competitors (including other monopolists) able to supply alternative products at a lower price. Nevertheless, in reality, there existed not one, but two kinds of "average profit rates" in capitalist production: a higher one for corporations in the monopolized sectors of product markets, and a lower one for smaller firms in the non-monopolized sectors.[251] Together with the anarcho-communist Daniel Guérin, Mandel published a survey of economic concentration in the United States.[252]

Post-war boom

In the 1970s, there were two main debates about profitability among the Western New Left Marxists, one empirical, the other theoretical.

Profit squeeze

The empirical debate concerned the causes of the break-up of the long postwar boom. Orthodox Marxists like David Yaffe, for example, argued that the cause was the TRPF, while other Marxists (and non-Marxists) argued for a "profit squeeze" theory.[253]

According to the profit squeeze theory, profits fell essentially because, in the course of the long boom, demand for labour grew more and more, so that unemployment reduced to a very low level. This allowed workers to pick and choose their jobs, meaning that employers had to pay extra to attract and keep their staff. The increased labor costs therefore "squeezed" profits. This could be sustained for some time, while markets were still growing, but at the expense of accelerating price inflation. As their input prices and costs increased, business owners raised their own output prices, which fed the inflationary spiral. In the 1970s, employers began to scale back their investments in production, and there was enormous political pressure on the state to curb wage increases and reduce price inflation, bringing the long post-war boom to an end.[254]

Orthodox Marxists however argued that the main cause of falling profits was the rising organic composition of capital, and not wage rises. On this view, the falling average rate of profit on production capital in the end "choked off"[255] the growth of the total mass of profit, leading to a stagnation of business investment and rising unemployment.

Yaffe became quite famous. In a 1980s satire about the British far Left, John Sullivan stated that Yaffe had done "sterling work on the velocity of the falling rate of profit, and has almost got it down to the nearest foot per second."[256] Yaffe claimed that "It is precisely the crisis of profitability that makes a growing state expenditure necessary."[257] This idea was strongly criticized by Ian Gough.[258]

Neo-Ricardianism

The theoretical New Left debate in the 1970s was a clash[259] between orthodox Marxists believing in a labor theory of value[260] and neo-Ricardian socialists inspired by Piero Sraffa.[261][262] The neo-Ricardian socialists, basing themselves on the ideas of Maurice Dobb, Ronald L. Meek, Michio Morishima, and Ian Steedman, believed that Sraffa's models had made Marx's value theory redundant, and that Marx's TRPF theory was mathematically incoherent once it was rigorously modeled.[263] Sraffa's theory was not incompatible with some kind of labor theory of value as such, as several neo-Ricardians emphasized,[264] but it was incompatible with Marx's TRPF.[265] This debate still continues.[266]

The overall Marxist criticism of the neo-Ricardian socialists was, that they treated Marx as if he was a Sraffian. But, they claimed, Marx wasn't a Sraffian, because Marx's concepts were really quite different.[267] The Sraffians believed, that if Marx's theory cannot be restated in a mathematically consistent and measurable way, it has no scientific validity. Since the Marxists allegedly failed to formalize Marx's theory in a convincing way, the Sraffians dropped it, although they might still have socialist sympathies (Sraffa himself admired Marx, and was an avid collector of Marx memorabilia[268]).

Anwar Shaikh among others replied, that regrettably the mathematical formalizations offered by neo-Ricardian theorists to interpret Marx's idea were really more a sleight-of-hand, since, in the process of modelling, highly questionable assumptions were introduced which had nothing to do with Marx. Moreover, one could also use the same mathematical techniques with different assumptions, to compute results that were quite consistent with Marx's theory.[269][270] On his website, Andrew Kliman adopted the motto: "I ain't going to work on Piero's farm no more."

International Socialists and British Socialist Workers Party interpretation

In the 1990s, a leader of the British Socialist Workers Party, Chris Harman, advanced a reading of Marx that sees economic crisis as the main effective countervailing factor to the TRPF, but which places limits on its effectiveness as the capitalist system ages and units of capital become larger and more interlinked.[271] However, David Harvey mentions that in the Grundrisse, "Marx lists a variety of other factors that can stabilize the rate of profit 'other than by crises'."[272] Since the 1970s, the International Socialists have staged a theoretical struggle against underconsumptionism, regarded as a reformist ideology, and reaffirmed the TRPF as the true revolutionary theory.[273]

Empirical studies

Since the theoretical disputes failed to clinch the argument, more scholars raised the question of whether the theory of the falling rate of profit corresponded to the facts. They wanted to "count the horse's teeth" empirically, to shed light on the issue.

In the United States, pioneering empirical research on the average rate of profit was published from 1979 onward by Edward N. Wolff[274][275] and Thomas Weisskopf,[276] followed by Anwar Shaikh.[277] After some articles, Fred Moseley also published a booklength analysis of the falling rate of profit.[278] Wolff and Moseley together edited an international study.[279]

In the 1980s, the Italian scholar Angelo Reati, who worked for the European Commission in Brussels and who tried to combine Marxian, neo-Ricardian and Post-Keynesian approaches, analyzed industrial profitability data for Italy, the UK, France, and Germany. This resulted in a series of papers, and a book in French.[280] Gérard Duménil, Mark Glick and José Rangeĺ studied the empirical tendency of the rate of profit to fall in the United States using a variety of sources.[281][282]

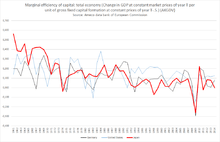

An important econometric work, Measuring the Wealth of Nations, was published by Anwar Shaikh and Ertuğrul Ahmet Tonak in 1994.[283] This work sought to reaggregate the components of official gross output measures and capital stocks rigorously, to approximate Marxian categories, using some new techniques, including input-output measures of direct and indirect labor, and capacity utilization adjustments. Shaikh and Tonak argued that the falling rate of profit is not a short-term trend of the business cycle, but a long-term historical trend. According to their calculations, the Marxian rate of profit on production capital fell throughout most of the long boom of 1947–1973, despite an enormous expansion of the volume (mass) of profit.

The celebrated New Left historian Robert Brenner from California has also attempted to provide an explanation of the postwar boom and its aftermath in terms of profitability trends.[284] Brenner's interpretation was heavily criticized by Anwar Shaikh, who argued that it is not really credible from an econometric or theoretical point of view.[285] According to Shaikh, Brenner had an inflated view of American factories, to the point where Brenner believed that the profitability of US manufacturing determined the destiny of the whole world economy. In reality, US factory production wasn't that big.

A lot of detailed work on long run profit trends was done by the French Marxist researchers Gerard Duménil and Dominique Lévy.[286]

In Britain, the Oxford group around Andrew Glyn used mainly OECD-based profitability data to analyze longterm trends.[287][288][289][290]

Prof. Lefteris Tsoulfidis, based at the University of Macedonia, has participated in a lot of sophisticated empirical research on profitability.[291]

This type of research was replicated by Marxian scholars in many other countries around the world, who often introduced their own technical refinements in the data sets.[292]

Theoretical works

In the course of the 1990s, many leftist academics lost interest in Sraffian economics. Although he had written a few articles and edited the collected works of David Ricardo, Sraffa had authored only one book himself,[293] a neo-Ricardian analysis about the distribution of value-added from production among workers and capitalists (Sraffa calls net value-added the "surplus"[294][295]). While Sraffa had provided an alternative to the problematic labor theory of value of the orthodox Marxists, while undermining the marginalist theory of capital, Sraffa's book provided no answers to many important contemporary macroeconomic issues. It was not designed for that purpose. For example, "The Sraffa system, like many stationary-state general equilibrium models, contains no good which, uniquely, possesses all the important features of money."[296]

Michał Kalecki

Instead, many Marxists and leftists became more focused on the political economy of Michał Kalecki, who tried to combine Marxian and Keynesian economics in a more realistic way, without relying on any labor theory of value.[297][298] Kalecki also believed in a cyclical tendency for profits to fall, but more as a result of the changing balance of power between the working class and the capitalist class, or changes in capital intensity.[299][300][301]

Stephen Cullenberg

In 1994, Stephen Cullenberg published a book on the falling rate of profit which reviewed the whole controversy to date (with special attention to Okishio's Theorem).[302]

Temporal single-system interpretation

Reviving and developing ideas first mooted in the 1980s,[303] proponents of the temporal single-system interpretation (TSSI) such as Andrew Kliman, Alan Freeman,[304] Paolo Giussani and Guglielmo Carchedi have argued from the 1990s onward that the arguments by von Böhm-Bawerk, Bortkiewicz, and Okishio do not refute Marx's case.[305]

Kliman argues in Reclaiming Marx's Capital (2007) that the apparent inconsistency of Marx's case arises out of a misreading of Marx through the prism of general equilibrium theory and double-entry accounting.

Once the operations of capitalist production are interpreted as "temporal and sequential" (as opposed to a "simultaneist" model where inputs and outputs are valued simultaneously, so that total input and total output valuations are always exactly equal) and "single-system" (where values and prices always co-exist, and are co-dependent, not separate systems), it is argued that the transformation problem disappears, and that the TRPF can no longer be dismissed on logical grounds.[306]

Criticism of TSSI

The modern TSSI approach has been criticized by other Marxist and neo-Ricardian scholars including Gérard Duménil, Duncan K. Foley, Michel Husson, David Laibman, Dominique Lévy, Simon Mohun, Gary Mongiovi, Ernesto Screpanti, Ajit Sinha, and Roberto Veneziani.[307]