Sderot

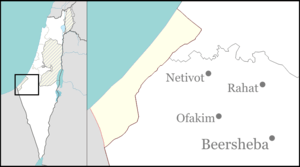

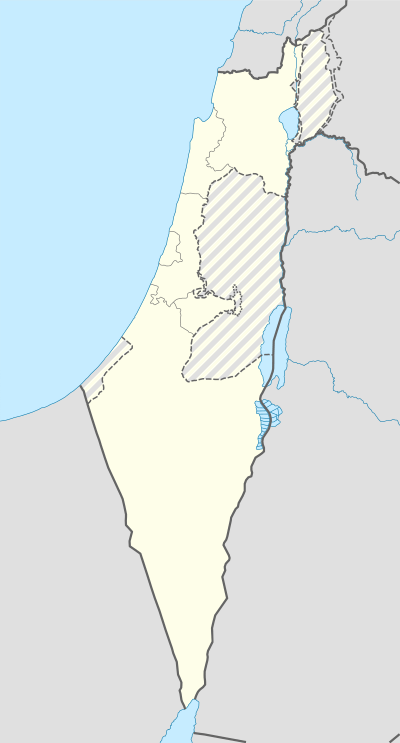

Sderot (Hebrew: שְׂדֵרוֹת, Hebrew pronunciation: [sdeˈʁot], lit. Boulevards, Arabic: سديروت) is a western Negev city and former development town in the Southern District of Israel. In 2018 it had a population of 26,455.[1]

Sderot

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Śderot |

| |

| |

Sderot  Sderot | |

| Coordinates: 31°31′22″N 34°35′43″E | |

| District | Southern |

| Founded | 1951 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City (from 1996) |

| • Mayor | Alon Davidi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,472 dunams (4.472 km2 or 1.727 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 26,455 |

| • Density | 5,900/km2 (15,000/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | Boulevards/avenues |

Sderot is located less than a mile from Gaza (the closest point is 840 m),[2] and is notable for having been a major target of Qassam rocket attacks from the Gaza Strip. Between 2001 and 2008, rocket attacks on the city killed 13 people, wounded dozens, caused millions of dollars in damage and profoundly disrupted daily life.[3] Although rocket fire subsided after the Gaza War, the city has come under rocket attack on occasion since that time.

History

Sderot was originally founded in 1951 as a transit camp called Gabim Dorot for Israeli immigrants, primarily from Kurdistan and Iran, who numbered 80 families.[4] The development was located on the land of the Palestininan village of Najd which was depopulated during 1948 Arab-Israeli War[5][6] and served as part of a chain of settlements designed to block infiltration from Gaza.[7][8] Permanent housing was completed three years after the transit camp's establishment in 1954.[8] The town was renamed Sderot after the Eucalyptus boulevard planted along the length of the town,[9] whose planting provided employment to the residents of the settlement.

From the mid-1950s Moroccan Jews increasingly settled in the township.[7][10] Romanian Jewish and Kurdish Jewish immigrants also began settling in Sderot. In 1956, Sderot was recognized as a local council.[11] In the 1961 census, the percentage of North African immigrants, mostly from Morocco, was 87% in the town; another 11% of the residents were immigrants from Kurdistan.[12]

Sderot received a symbolic name, after the numerous avenues and standalone rows of trees planted in the Negev, especially between Beersheba and Gaza, to combat desertification and beautify the arid landscape. Like many other localities in the Negev, Sderot's name has a green motif that symbolizes the motto "making the desert bloom", a central part of Zionist ideology.[13]

| Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel |

|---|

|

| By year (List) |

|

| Groups responsible |

|

| Rocket types |

| Cities affected |

| Regional Council areas affected |

|

Hof Ashkelon

Sdot Negev

|

| Settlements affected (evacuated) |

| Defense and response |

| See also |

|

Sderot absorbed another large wave of immigrants from the former Soviet Union during the 1990s Post-Soviet aliyah, doubling its population. In 1996, it was declared a city.

During the Second Intifada, the city became a target for rockets from the Gaza Strip, starting in 2001.[14] Rocket fire intensified after the Israeli disengagement from Gaza in 2005.[15] The population declined as families left the city in desperation.

During the Gaza War in December 2008 and January 2009, between 50 and 60 rockets were fired at Sderot per week, causing about half the city's residents to temporarily evacuate. The war ended regular rocket fire from Gaza and the city experienced a revitalization. By 2009, demand for apartments was outweighing supply, a new sports complex largely funded by donor aid had opened, a new shopping mall was being built, and the assistance that the city had received due to concern over the years of rocket fire meant that Sderot now had better community, educational, and recreational services than many other Negev development towns.[16] The city sustained rocket fire on occasion over the following years, including during Operation Protective Edge.[17] However, the introduction of the Iron Dome rocket defense system reduced the effectiveness of this rocket fire, with many of these rockets being intercepted.

In May 2011, the British Ambassador to Israel visited Sderot and met with Mayor David Buskila, who described the suffering of children in both Sderot and Gaza:[2]

"Believe me that I feel bad for my children, for the children that live here in Sderot, but I also feel pain for the children that live in the other side of the border in Gaza ... This situation that the children from this place and the other place is because of the behaviour of the leaders of the terror organisations. We can create another quality of life, it is so close."

In October 2013, Alon Davidi was elected as Mayor of Sderot.

Demographics

According to CBS, in 2010 the city had a population of 21,900. The national makeup of the city was 94% Jewish, 5.5% other non-Arabs, and Arabs less than 1%. There were 10,600 males and 10,500 females. The population growth rate in 2010 was 0.5%.

A number of Palestinians from the Gaza Strip were resettled in Sderot beginning in 1997 after cooperating with the Shin Bet.[18]

Economy

In 2008, the average wage for a salaried worker in Sderot was NIS 5,261.[19]

Hollandia International, founded in 1981, a company that manufacturers and exports high-end mattresses, moved its sole manufacturing center to Sderot 11 years ago. Following the rocket attacks, Hollandia has been forced to relocate.

The Osem plant in Sderot, opened in 1981, is the region's major employer, with 480 workers. 170 products are manufactured there, including Bamba, Bisli, Mana Hama instant noodle and rice dishes, instant soup powders, shkedei marak, ketchup and sauces.[20]

The Menorah Candle factory located in Sderot exports Hanukkah candles all over the world.[21]

Nestlé maintains a research and development facility in Sderot,[22] established in 2002. Its production facilities for breakfast cereals are also located in Sderot.[23]

Amdocs has a plant in the Sderot and an industrial zone is under development.[24]

In 2012, the government approved nearly $59 million worth of economic benefits for Sderot to strengthen the economy, boost employment and subsidize psycho-social programs for the city's residents.[25]

Local government

In 2010, after a decline in charitable donations, the municipality revealed that it was on the verge of bankruptcy.[26]

Education

According to CBS, there are 14 schools and 3,578 students in the city. They are spread out as eleven elementary schools and 2,099 elementary school students, and six high schools and 1,479 high school students. 56.5% of 12th grade students were entitled to a matriculation certificate in 2001. Sapir Academic College[27] and the Hesder Yeshiva of Sderot are located in Sderot. All schools in the city and 120 bus stops have been fortified against missile attacks.[28]

Culture

An unusually high ratio of singers, instrumentalists, composers and poets have come from Sderot.[29]

Several popular bands have been formed by musicians who practiced in Sderot's bomb shelters as teenagers.[30][31][32] As an immigrant town with high unemployment experiencing a dramatic musical success, as bands blend international sounds with the music of their Moroccan immigrant parents, it has been compared to Liverpool in the 1960s.[33][34] Among the notable bands are Teapacks[35] Knesiyat Hasekhel and Sfatayim.[36] Well-known musicians from Sderot include Shlomo Bar, Kobi Oz, Haïm Ulliel and Smadar Levi. The winner of the Israeli version of "American Idol" 2011 was Hagit Yaso, a local Sderot singer of Ethiopian origin.

Israeli poet Shimon Adaf was born in Sderot,[29] as well as the actor and entertainer Maor Cohen. Adaf dedicated a poem to the city in his 1997 book Icarus' Monologue.

In 2007, Jewish-American documentary filmmaker Laura Bialis immigrated to Israel, and decided to settle in Sderot "to find out what it means to live in a never-ending war, and to document the lives and music of musicians under fire".[37] Her film Sderot: Rock in the Red Zone focuses on young musicians living under the daily threat of Qassams.[38][39][40]

Politically, the town leans heavily to the right.[41]

The Israeli musician Dror Kessler, who lives in Sderot, has published Intifada Solitaire, a music album recorded during “Operation Protective Edge”, in which he expressed a unique and local opinion, one that may be considered to be leaning to the left.

Sderot cinema

Sderot cinema is a name given to gatherings at a hill in Sderot, where over 50 locals would come to watch the fighting in the Gaza strip during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict, cheering when bombs would strike.[42][43][44][45][46] The name was coined by a Danish journalist who snapped a photo of it and posted it on Twitter.[47][48][49][50] Similar events happened in Operation Cast Lead in 2009,[51] after which some critics decided to refer to the hill as "Hill of Shame".[52]

Sderot residents have complained about the media portrayal.[53] Marc Goldberg noted in The Times of Israel that "it shouldn't surprise anyone that after suffering a huge amount of shelling over the course of several years, they are cheering the IDF attacking the weapons that have been turned on them."[54]

Rocket fire from Gaza

Sderot lies one kilometer (0.62 miles) from the Gaza Strip and town of Beit Hanoun. Since 2001, during the beginning stage of the Second Intifada, and more so since the Israeli disengagement from Gaza in 2005, the city sustained constant rocket fire from Qassam rockets launched by Hamas and Islamic Jihad.[55] The city continued to suffer from rocket fire until the Gaza War's end in 2009, which brought an end to regular rocket fire aimed at the city. However, the city has still suffered from rocket fire on occasion ever since. Despite the imperfect aim of these homemade projectiles, they caused deaths and injuries, as well as significant damage to homes and property, psychological distress and emigration from the city. The Israeli government installed a "Red Color" (צבע אדום) alarm system to warn citizens of impending rocket attacks, although its effectiveness was questioned. Citizens were only given 7–15 seconds to reach shelter after the sounding of the alarm.

In May 2007, a significant increase in shelling from Gaza prompted the temporary evacuation of thousands of residents.[56] By November 23, 2007, 6,311 rockets had fallen on the city.[57] Yediot Ahronoth reported that during the summer of 2007, 3,000 of the city's 22,000 residents (consisting mostly of the city's key upper and middle class residents) left for other areas, out of Qassam rocket range. Russian billionaire Arcadi Gaydamak organised a series of relief programs for residents unable to leave.[58] On December 12, 2007, after more than 20 rockets landed in the Sderot area in a single day, including a direct hit to one of the main avenues, Sderot mayor Eli Moyal announced his resignation, citing the government's failure to halt the rocket attacks.[59] Moyal was persuaded to retract his resignation.

In January 2008, British journalist Seth Freedman of The Guardian described Sderot as a city of near-deserted streets and empty malls and cafes.[60] In March 2008, the mayor said that the population had dropped by 10–15%, while aid organizations said the figure was closer to 25%. Many of the families that remained were those who could not afford to move out or were unable to sell their homes.[61] Studies found that air raid sirens and explosions have caused severe psychological trauma in some residents.[62] According to a study carried out at Sapir Academic College in 2007, some 75% of residents aged 4-18 were suffering from PTSD, including sleeping disorders and severe anxiety, in the wake of rocket attacks on the city, and 1,000 residents were receiving psychiatric treatment at the community mental health center.[63][64] From mid-June 2007 to mid-February 2008, 771 rockets and 857 mortar bombs were fired at Sderot and the western Negev, an average of three or four each a day.[65]

Casualties

| Name | Age upon death | Date of death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mordechai Yosepov | 49 | June 28, 2004 | |

| Afik Zahavi | 4 | June 28, 2004 | |

| Yuval Abebeh | 4 | September 24, 2004 | |

| Dorit (Mesarat) Benisian | 2 | September 24, 2004 | |

| Ayala-Haya (Ella) Abukasis | 17 | January 21, 2005 | Critically wounded on January 15, 2005 |

| Fatima Slutsker | 57 | November 16, 2006 | |

| Yaakov Yaakobov | 43 | November 21, 2006 | |

| Shirel Friedman | 32 | May 21, 2007 | |

| Oshri Oz | 36 | May 27, 2007 | |

| Roni Yihye | 47 | February 27, 2008 | |

| Shir-El Friedman | 35 | May 19, 2008 | |

Solidarity gestures

In a gesture of solidarity, El Al (Israel's national airline) named one of its Boeing 777 passenger planes Sderot (4X-ECE).[66][67]

In January 2008, the Jewish Community Relations Council of New York organized a display of 4,200 red balloons outside the headquarters of the United Nations.[68] Each balloon represented a Qassam rocket that had been fired into Sderot,[69] where for years the town and its surrounding area have been under near-constant bombardment by thousands of rockets and mortar shells fired from Gaza.[70] Consul David Saranga, who conceptualized the display, said he used the balloons as an opportunity to call upon the international community to stop ignoring what's happening in Israel.[71] The balloon display made headlines in New York City papers as well as international publications.[72]

In May 2019, the Israeli Air Force held a special flypast (aerial display) over Sderot (in addition to Yom Ha'atzmaut flypast), in order to salute the residents of Sderot who suffer continuously from Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel.

Lawsuits

In 2011, a Sderot resident filed a million dollar lawsuit against two Canadian organizations raising funds for a Canadian ship to join the Gaza flotilla. According to the lawyers, "The Canadian Boat's raison d'être is to aid and abet the terrorist organization that rules Gaza." The suit alleges that these actions violate Canadian laws that prohibit aid to terror groups.[73]

Transportation

Sderot is accessible by Highway 34 and Route 232.

The Ashkelon–Beersheba railway, a new railway line which connected Sderot with Tel Aviv and Beersheba, was inaugurated in December 2013. The Sderot railway station located on the outskirts of the city at the southern entrance, was opened on December 24, 2013. It is the first in Israel to be armored against rocket fire.[74]

Notable residents

- Erez Biton, poet

- Miri Bohadana, model

- Kim Edri, beauty queen, and former Miss Israel

- Kobi Oz, musician

- Amir Peretz, politician former defense minister

- Hagit Yaso, singer

See also

- List of Israeli twin towns and sister cities

- Merkhav Mugan

- Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel

- Jewish Agency for Israel

References

- "Population in the Localities 2018" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 25 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- "Ambassador visits Sderot, impressed by 'spirit of town'". Ukinisrael.fco.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 2012-03-18. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Avi Issacharoff; Mijal Grinberg. "2 Israelis Lightly Wounded as 33 Rockets Slam in Western Negev". Haaretz. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- Israel Directory, Miksam Limited, 2003 p.212.

- Morris, Benny (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- All that remains : the Palestinian villages occupied and depopulated by Israel in 1948. Khalidi, Walid. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Palestine Studies. 1992. ISBN 0-88728-224-5. OCLC 25632612.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Anton La Guardia, Holy Land, Unholy War: Israelis and Palestinians, Penguin 2007 p.311

- "Gimme shelter". Heebmagazine.com. 2009-03-24. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- HaReuveni, Immanuel (1999). Lexicon of the Land of Israel (in Hebrew). Yedioth Ahronoth Publishing. ISBN 965-448-413-7.

- "Sderot - Jewish Virtual Library". jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- HaReuveni (1999), p. 908

- Rapoport, Meron (2007-05-25). "The Pioneers of Sderot". Haaretz. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- Sasson (2010), p. 137

- "This Week in History: The first Kassam hits Sderot - Features - Jerusalem Post".

- "As the Rockets Continue to Fall, Anxiety and Depression Grip Sderot". 2006-12-05.

- "In Israel, embattled Sderot comes back to life after rocket barrages of Gaza war". Christian Science Monitor. 2009-12-31.

- "In rocket-battered Sderot, waiting for the next war".

- Hadad, Shmulik (2007-05-30). "Palestinian Collaborator: Terrorists Only Understand Force". Ynetnews. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Aizescu, Sivan (2008-04-02). "Survey: Consumers in the sticks are paying through the nose". English.themarker.com. Archived from the original on 2011-12-19. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Tsoref, Ayala (2009-08-27). "Nestle honcho drops in to see Bamba baby". Haaretz. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- Azoulay, Yuval (2009-12-11). "Hanukkah miracles all around". Haaretz. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- "R&D Sderot, Israel". Nestle.com. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- "Nestle producing new breakfast cereal in Sderot - Israel Business, Ynetnews". Ynetnews. 1995-06-20. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- Arik Mirovsky (July 30, 2012). "Sderot comes back to life". Haaretz. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Marcy Oster (January 1, 2012). "Sderot and environs get $59 million in gov't benefits for '12". Jta.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Yanir Yagna (March 24, 2010). "Rocket-battered Sderot faces bankruptcy". Haaretz. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Sapir Academic College Archived January 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Margot Dudkevitch (15 November 2011). "Living under the rocket's roar". The Jerusalem Report. Jpost.com. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Geer Fay Cashman (June 24, 2006). "Grapevine: Away from the rockets' red glare". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Cobi Ben-Simhon (August 8, 2007). "Sounds from another country". Haaretz. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- "Sderot, A Love Story, The Jewish Week, Gary Rosenblatt, 06/18/2008". Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- "Borderland Pop: Arab Jewish Musicians and the Politics of Performance", Galit Saada-Ophir, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Cultural Anthropology Volume 21 Issue 2, Pages 205–233, 7 Jan 2008

- Teapacks interview, Caroline Westbrook, something Jewish, 09/05/2007

- "The Official Sderot Movie Website :: Movie : Music : Musicians". Sderotmovie.com. 2008-12-13. Archived from the original on 2010-03-12. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- "teapacks". teapacks. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- "Sefatayim". Israel-music.com. Retrieved 2010-04-04.

- "Rockets may fall, but Sderot continues to rock". 2009-01-15. Archived from the original on 2009-01-24. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- Zaitchik, Alexander (2008-03-16). "Documentary Pulls Back Iron Curtain". The Forward. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Fuma, Simona (2008-04-23). "Rebel With a Cause". World Jewish Digest. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Lash Balint, Judy (2008-03-02). "Only Thirty-Six Hours in Sderot". San Diego Jewish World. Archived from the original on 2008-08-30. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "Likud in Jerusalem, Zionist Union in Tel Aviv". The Times of Israel.

- "'Sderot cinema': Israelis watch bombings". Stuff.

- "These Israelis Eat Popcorn At 'Sderot Cinema' As They Watch Bombs Fall On Gaza". The Huffington Post UK. 2014-07-13.

- "Popcorn at front-row seats of war". NewsComAu. 13 July 2014.

- "Why Israel's #SderotCinema – people gathering to watch live bombing of Gaza – should make us all uncomfortable". dna. 14 July 2014.

- "Israelis watch Gaza pounding from front-row seats munching popcorn". The Times of India.

- "Al Aravya: 'Sderot cinema:' Israelis watch latest from Gaza". alarabiya.net.

- "When bombs receive applause". Kristeligt Dagblad. 2014-07-11.

- "Al Jazeera: 'Sderot cinema': Image shows Israelis gathering to watch nighttime attacks on Gaza". Archived from the original on July 12, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2019.

- "Twitter photo showing Israelis 'cheering' Gaza bombing goes viral". The Jerusalem Post - JPost.com.

- Israelis Watch Bombs Drop on Gaza From Front-Row Seats. New York Times, 14 July 2014

- Hill of Shame where Gaza bombing is spectator sport. Martin Fletcher and Yonit Farago, The Times, 13 January 2009

- "Viewers at 'Sderot cinema' complain over media portrayal". Middle East Eye.

- "In defense of the Sderot cinema". The Times of Israel.

- Silverman, Anav (2007-09-20). "A City Under Siege: An Inside View of Sderot, Israel". Sderot Media Center. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Kershner, Isabel (2007-05-31). "Israeli Border Town Lives in the Shadow of Falling Rockets". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on March 8, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Sackett, Shmuel (2007-12-07). "23 Years and 6,311 Rockets". web.israelinsider.com. Archived from the original on 2008-07-06. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "3,000 Sderot Residents Have Left Town". The Jerusalem Post. 2007-11-16. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- "Israeli Mayor Quits Over Rockets". BBC Online. 2007-12-12. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Freedman, Seth (January 18, 2008). "Sderot: beseiged and abandoned". Retrieved August 18, 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- Hadad, Shmulik (2008-03-19). "Sderot: Those Who Can Afford It Have Already Left". Ynetnews. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- Sharfman, Jake (2009-12-17). "Tiny organization fights to make Sderot's voice heard". Haaretz. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- Ginter, Davida (2007-11-26). "כך הפקירה המדינה את נפגעי החרדה". Natal.org.il. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- "IRIN Middle East - ISRAEL-OPT: Relentless rocket attacks take psychological toll on children in Sderot - Israel - OPT - Children - Conflict - Health & Nutrition". IRINnews. 2008-01-27.

- "Qassam Rockets — Background and Statistics". Zionism-Israel.com. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "Boeing 777 Named for Sderot". infolive.tv. 2007-07-31. Retrieved 2008-10-20.

- "Production List Search". Planespotters.net. Retrieved 2012-06-07.

- 4,200 balloons released in NY to protest Qassam fire, By Neta Sela, Ynet News, January 24, 2008.

- "Israeli mission in N.Y. displays 4,200 balloons, one for each Qassam". Haaretz. January 25, 2008. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009.

- Itamar Sharon (January 24, 2008). "Balloon for each Kassam on UN doorstep". The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Meet David Saranga, the man whose campaigns are rebranding Israel, David Russell, The Jewish Chronicle, Published May 23, 2008.

- Balloons for Sderot, AP Images, Published January 2008. (subscription required)

- Friedman, Ron (June 8, 2011). "Sderot rocket victims sue Gaza flotilla organizers". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 2014-02-05.

- "In first, Sderot train chugs into rocket-protected station". The Times of Israel.

- Sderotplatz in Zehlendorf June 10, 2009. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

Bibliography

- HaReuveni, Immanuel (1999). Lexicon of the Land of Israel (in Hebrew). Yedioth Ahronoth Publishing. ISBN 965-448-413-7.

- Avi Sasson, ed. (2010). Sderot (in Hebrew). Ariel Publishing and Makom Company.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sderot. |

- Sderot Media Center

- The Other Voice

- Humanitarian aid organization in Sderot

- Sderot; The Movie

- Sderot portal—Hebrew

- Sderot Information Center for the Western Negev

- The committee for a secure Sderot

- Sderot in The Washington Post

- Sderot Journal: An Israeli Playground, Fortified Against Rockets