Real ID Act

The Real ID Act of 2005, Pub.L. 109–13, 119 Stat. 302, enacted May 11, 2005, is an Act of Congress that modifies U.S. federal law pertaining to security, authentication, and issuance procedure standards for drivers' licenses and identity documents, as well as various immigration issues pertaining to terrorism.

.svg.png) | |

| Other short titles |

|

|---|---|

| Long title | An Act to establish and rapidly implement regulations for state driver's license and identification document security standards, to prevent terrorists from abusing the asylum laws of the United States, to unify terrorism-related grounds for inadmissibility and removal, and to ensure expeditious construction of the San Diego border fence. |

| Nicknames | Real ID Act of 2005 |

| Enacted by | the 109th United States Congress |

| Effective | |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 109-13 |

| Statutes at Large | 119 Stat. 302 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 8 U.S.C.: Aliens and Nationality |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 8 U.S.C. ch. 12, subch. I § 1101 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

|

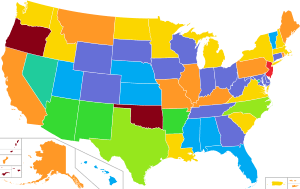

2012

2013

2014

2016

2017 |

2018

2019

2020

Granted extension or under review |

The law sets forth requirements for state drivers' licenses and ID cards to be accepted by the federal government for "official purposes", as defined by the Secretary of the United States Department of Homeland Security. The Secretary of Homeland Security has defined "official purposes" as boarding commercially operated airline flights, and entering federal buildings and nuclear power plants, although the law gives the Secretary unlimited authority to require a "federal identification" for any other purposes.[4]

The Real ID Act implements the following:

- Title II of the act establishes new federal standards for state-issued drivers' licenses and non-driver identification cards.

- Changing visa limits for temporary workers, nurses, and Australian citizens.

- Funding some reports and pilot projects related to border security.

- Introducing rules covering "delivery bonds" (similar to bail, but for aliens who have been released pending hearings).

- Updating and tightening laws on application for asylum and deportation of aliens for terrorism.

- Waiving laws that interfere with construction of physical barriers at the borders.

On December 20, 2013, the Department of Homeland Security announced that implementation of Phase 1 would begin on January 20, 2014, which followed a yearlong period of "deferred enforcement". There are four planned phases, three of which apply to areas that affect relatively few people—e.g., DHS headquarters, nuclear power plants, and restricted and semi-restricted federal facilities such as military bases.[5] On January 8, 2016, DHS issued an implementation schedule for Phase 4, stating that starting January 22, 2018, passengers with a driver's license issued by a state that is not compliant with the REAL ID Act (and has not been granted an extension) will need to show an alternative form of acceptable identification for domestic air travel to board their flight. Starting October 1, 2021 (originally scheduled for October 1, 2020 but was postponed a year due to a global coronavirus pandemic[6]), every air traveler will need a REAL ID-compliant license or another acceptable form of identification (such as a U.S. passport, U.S. passport card, U.S. military card, or DHS trusted traveler card, e.g. Global Entry, NEXUS, SENTRI, FAST) for domestic air travel.[7][8][6] As of April 2020, all states and territories have been certified as compliant except Oklahoma, Oregon (granted extensions), American Samoa and Northern Mariana Islands (under review).[9]

Legislative history

The Real ID Act started off as H.R. 418, which passed the House[10] in 2005 and went stagnant. Representative James Sensenbrenner (R) of Wisconsin, the author of the original Real ID Act, then attached it as a rider on a military spending bill, H.R. 1268, the Emergency Supplemental Appropriations Act for Defense, the Global War on Terror, and Tsunami Relief, 2005. The House of Representatives passed that spending bill with the Real ID rider 368–58,[11] and the Senate passed the joint House–Senate conference report on that bill 100–0.[12] President Bush signed it into law on May 11, 2005.[3]

Congressional efforts to change or repeal the Real ID Act

On February 28, 2007, U.S. Senator Daniel Akaka (D-HI) introduced the Senate Bill S. 717, "Identification Security Enhancement Act of 2007", subtitled: "A bill to repeal title II of the REAL ID Act of 2005, to restore section 7212 of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, which provides States additional regulatory flexibility and funding authorization to more rapidly produce tamper- and counterfeit-resistant drivers' licenses, and to protect privacy and civil liberties by providing interested stakeholders on a negotiated rulemaking with guidance to achieve improved 21st century licenses to improve national security".[13] The bill was co-sponsored by Senators Lamar Alexander (R-TN), Max Baucus (D-MT), Patrick Leahy (D-VT), John E. Sununu (R-NH), Jon Tester (D-MT). The bill was read twice and referred to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary on February 28, 2007.

A similar bill was introduced on February 16, 2007, in the U.S. House of Representatives by Rep. Thomas Allen (D-ME), with 32 co-sponsors (all Democrats). The House bill, H.R. 1117, "REAL ID Repeal and Identification Security Enhancement Act of 2007", is subtitled: "A bill to repeal title II of the REAL ID Act of 2005, to restore section 7212 of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004, which provides States additional regulatory flexibility and funding authorization to more rapidly produce tamper- and counterfeit-resistant drivers' licenses, and to protect privacy and civil liberties by providing interested stakeholders on a negotiated rulemaking with guidance to achieve improved 21st century licenses to improve national security."[14] On May 23, 2007, the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee referred H.R. 1117 to the Subcommittee on Government Management, Organization, and Procurement.

A more limited bill, S. 563, that would extend the deadlines for the states' compliance with the Real ID Act, was introduced on February 13, 2007, in the U.S. Senate by Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME), together with Senators Lamar Alexander (R-TN), Thomas Carper (D-DE), Charles Hagel (R-NE), and Olympia Snowe (R-ME).[15]

Postponement

As passed by Congress, implementation of the Real ID Act was to be done in phases to ensure that it was to be executed in a way that was both fair and responsible. The DHS outlines a commitment to timely implementation of the four phases of the act and assert that the availability of extensions should not be assumed. However, this decision to implement the act in a gradual way resulted in postponement from the federal end.[16] On March 2, 2007, it was announced that enforcement of the Act would be postponed until December 2009.[17] On January 11, 2008, it was announced that the deadline has been extended again to 2011.[18] On the same date the Department of Homeland Security released the final rule[19] regarding the implementation of the drivers' licenses provisions of the Real ID Act.[20] Although initially cautioned against, state extensions for compliance were authorized by the DHS which further postponed enactment. Extensions for states were granted by the Secretary of Homeland Security after the provision of satisfactory justification.[21]

Implementation progress

As of April 2, 2008, all 50 states had either applied for extensions of the original May 11, 2008 compliance deadline or received unsolicited extensions.[22] As of October 2009, 25 states approved either resolutions or binding legislation not to participate in the program. When President Obama selected Janet Napolitano (a prominent critic of the program) to head the Department of Homeland Security, the future of the law was considered uncertain,[23] and bills were introduced into Congress to amend or repeal it.[24] In 2009, the most recent of these, would have eliminated many of the more burdensome technological requirements but still require states to meet federal standards in order to have their ID cards accepted by federal agencies.

There are four planned phases, each one beginning with a "notification period". Noncompliant IDs continue to be accepted during the notification period, as well as afterwards if their respective state or territory is granted an extension, until a final deadline for all phases.

- Phase 1: restricted areas at the DHS headquarters on Nebraska Avenue

- January 20, 2014 – notification period

- April 21, 2014 – enforcement, but extensions may be granted

- Phase 2: restricted areas for all federal facilities and nuclear power plants

- April 21, 2014 – notification period

- July 21, 2014 – enforcement, but extensions may be granted

- Phase 3: semi-restricted areas for remaining federal facilities

- Phase 4: air travel[25]

- January 8, 2016 – notification period

- January 22, 2018 – enforcement, but extensions may be granted

- All phases

- October 1, 2021 – extensions no longer granted[6]

Analysis of the law

IDs and drivers' licenses as identification

In the United States, drivers' licenses are issued by the states, not by the federal government. Additionally, because the United States has no national identification card and because of the widespread use of motor vehicles, drivers' licenses have been used as a de facto standard form of identification within the country. For non-drivers, states also issue voluntary identification cards which do not grant driving privileges. Prior to the Real ID Act, each state set its own rules and criteria regarding the issuance of a driver's license or identification card, including the look of the card, what data is on the card, what documents must be provided to obtain one, and what information is stored in each state's database of licensed drivers and identification card holders.

Federally mandated standards for state drivers' licenses or ID cards

Driver's license implications

- Title II of Real ID – "Improved Security for Driver's License and Personal Identification Cards" – repeals the driver's license provisions of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act, enacted in December 2004.[26] Section 7212 of that law established a cooperative state-federal rule-making procedure to create federal standards for drivers' licenses. Instead, the Real ID Act directly imposed specific federal standards.

The Real ID Act Driver's License Summary details the following provisions of the Act's driver's license title:[27]

- Authority

- Data Retention and Storage

- DL/ID Document Standards

- Grants to States

- Immigration Requirements

- Linking of Databases

- Minimum DL/ID Issuance Standards

- Minimum Standards for Federal Use

- Repeal of 9/11 Commission Implementation Act DL/ID Provisions

- Security and Fraud Prevention Standards

- Verification of Documents

After 2011, "a Federal agency may not accept, for any official purpose, a driver's license or identification card issued by a state to any person unless the state is meeting the requirements" specified in the Real ID Act. The DHS will continue to consider additional ways in which a Real ID license can or should be used for official federal purposes without seeking the approval of Congress before doing so. States remain free to also issue non-complying licenses and IDs, so long as these have a unique design and a clear statement that they cannot be accepted for any federal identification purpose. The federal Transportation Security Administration is responsible for security check-in at airports, so bearers of non-compliant documents would no longer be able to travel on common carrier aircraft without additional screening unless they had an alternative government-issued photo ID.[28]

The national license/ID standards cover:

- How the states must share their databases both domestically and internationally through the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA)

- What data must be included on the card and what technology it is encoded with

- What documentation must be presented and electronically stored before a card can be issued

These requirements are not new. They replace similar language in Section 7212 of the Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 (Pub.L. 108–458), which had not yet gone into effect before being repealed by the Real ID Act.

Data requirements

A Real ID-compliant form of identification requires the following pieces of data:

- Full legal name

- Signature

- Date of birth

- Gender

- Unique identifying number

- Principal residence address

- Front-facing photograph of the applicant

Compliant IDs must also feature specific security features intended to prevent tampering, counterfeiting, or duplication of the document for fraudulent purposes. The cards must also present data in a common, machine-readable format (bar codes, smart card technology, etc.). Although the use of wireless RFID chips was offered for consideration in the proposed rulemaking process, it was not included in the latest rulemaking process.[29] DHS could consider additional technological requirements to be incorporated into licenses after consulting with the states. In addition, DHS has required the use of RFID chips in its Enhanced Driver's License program, which the Department has proposed as an alternative to REAL ID.[30]

Documentation required before issuing a license or ID card

Before a card can be issued, the applicant must provide the following documentation:[31]

- A photo ID, or a non-photo ID that includes full legal name and birthdate

- Documentation of birthdate

- Documentation of legal status and Social Security number

- Documentation showing name and principal residence address

Digital images of each document will be stored in each state DMV database.

Document verification requirements

Section 202(c)(3) of the Real ID Act[32] requires states to "verify, with the issuing agency, the issuance, validity, and completeness of each document" that is required to be presented by a driver's license applicant to prove his identity, birth date, legal status in the U.S., social security number and the address of his principal residence. The same section states that the only foreign document acceptable is a foreign passport.

The DHS final rule[19] regarding implementation of the Real ID Act driver's license provisions relaxes, and in some instances waives altogether, these verification requirements of the Real ID Act. Thus the DHS rule leaves the implementation of this verification requirement to discretion of states (page 5297 of the DHS final rule in the Federal Register).[19] However, the DHS rule, Section 37.11(c), mandates that REAL ID license applicants be required to present at least two documents documenting the address of their primary residence.

The DHS rule declines to implement as impractical the provision of the Act requiring verification of the validity of foreign passports presented by foreign driver's license applicants as proof of identity with the authorities that issued these foreign passports (page 5294 of the DHS final rule in the Federal Register).[19]

Section 37.11(c) of the DHS final rule allows states to accept several types of documents as proof of social security number: a social security card, a W-2 form, an SSA-1099 form, a non-SSA-1099 form, or a pay stub bearing the applicant's name and SSN. However, states are not required to verify the validity of these documents directly with their issuers (e.g. with the employer that issued a W-2 form or a pay stub). Instead, the DHS rule requires the states to verify the validity, and its match with the name given, of the social security number itself, via electronically querying the Social Security On-Line Verification (SSOLV) database managed by the Social Security Administration.

The DHS rule, Section 37.13(b)(3), specifies that the validity of birth certificates, presented to document the date of birth or to prove U.S. citizenship, should be verified electronically, by accessing the Electronic Verification of Vital Events (EVVE) system maintained by the National Association for Public Health Statistics and Information Systems (NAPHSIS), rather than directly with the issuers of the birth certificates (such as state vital records agencies).

Linking of license and ID card databases

Each state must agree to share its motor vehicle database with all other states. This database must include, at a minimum, all the data printed on the state drivers' licenses and ID cards, plus drivers' histories (including motor vehicle violations, suspensions, and points on licenses). Among other motivations, the database is intended to "improve the ability of law enforcement officers at all levels to confirm the identity of the individuals" holding an ID.[33]

The only system available with the capability to satisfy the Real ID Act requirements for database access is the "State to State" (S2S) system developed by the AAMVA and Clerus Solutions under contract with state motor vehicle licensing agencies ultimately funded by federal grants. A component of S2S is State Pointer Exchange Services (SPEXS), a central national database of "pointer" information about all Real ID compliant licenses and state ID cards.[34] The system also offers a "Verification of Legal Status" component which sends new entries to DHS for verification.[35]

Original legislation contained one of the most controversial elements which did not make it into the final legislation that was signed into law. It would have required states to sign a new compact known as the Driver License Agreement (DLA) as written by the Joint Driver's License Compact/ Non-Resident Violators Compact Executive Board with staff support provided by the American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators (AAMVA) and as approved by state Driver Licensing Agency representatives. The DLA is a consolidation of the Driver License Compact and the Non-Resident Violator Compact, which have 46 and 45 member states, respectively. The following controversial elements of the DLA are already in the existing compacts: a convicting state must report out-of-state convictions to the licensing state, states must grant license reciprocity to drivers licensed in other states, and states must allow authorities in other states access to driving records, consistent with the Driver Privacy Protection Act.

The requirement in the law for interstate access to state license and ID data has not been included in the DHS criteria for certification of state compliance or progress toward compliance.[36]

Foreign data sharing

New controversial requirements of the DLA are: (1) provinces and territories in Canada and states in Mexico are allowed to join the DLA and (2) member states, provinces, and territories are subject to reviews by DLA authorities for compliance with the provisions of the DLA. The DLA originated in concept with the 1994 establishment of a North American Driver License Agreement (NADLA) task force, and has created controversy among state representatives opposed to citizen data being shared with other countries.[37][38] According to a 2005 analysis of the DLA done by the National Conference of State Legislators, the DLA defines "jurisdiction" to allow participation by a territory or province of Canada and by any state of Mexico or the Federal District of Mexico. The DLA can be amended by a vote of at least two-thirds of the member jurisdictions.

Implementation

On January 11, 2008, DHS released the final rule regarding the implementation of the drivers' licenses provisions of the Real ID Act.[19] Under the DHS final rule, those states that chose to comply with Driver's License provisions of the Real ID Act are allowed to apply for up to two extensions of the May 11, 2008 deadline for implementing these provisions: an extension until no later than December 31, 2009 and an additional extension until no later than May 11, 2011. The DHS final rule mandates that, as of March 11, 2011, drivers' licenses issued by the states that are not deemed to be in full compliance with the Real ID Act, will not be accepted for federal purposes. The Secretary of Homeland Security is given discretion to determine the scope of such official purposes in the future.[39] For the states that do not apply to DHS by March 31, 2008 for an extension of the May 11, 2008 implementation deadline, that deadline will apply: after May 11, 2008, drivers' licenses issued by such states will not be accepted for federal purposes.

DHS announced at the end of 2013 that the TSA will accept state identification cards for commercial flights at least until 2016.[40]

After the final implementation deadline, some non-Real-ID–compliant licenses continued to be accepted for federal purposes, if DHS determines that the issuing state is in full compliance with the Real ID Act by the final implementation deadline. However, in order for their licenses to be accepted for federal purposes, people born after December 1, 1964, were to have been required to have Real-ID–compliant cards by December 1, 2014, and people born before December 1, 1964, by December 1, 2017. In December 2014, these deadlines were extended to October 1, 2020.[41] In March 2020, they were extended again to October 1, 2021.[6]

In March 2011 DHS further postponed the effective date of the Real ID Act implementation deadline until January 15, 2013.[42]

Immigration

As of May 11, 2005, several portions of the Real ID Act have imposed higher burdens and stricter standards of proof for individuals applying for asylum and other related forms of relief. For the first time, immigration judges can require an applicant to produce corroborating evidence (8 U.S.C. § 1229a(c)(4)(B). Additionally, the government may also require that an applicant produce corroborating evidence, a requirement that may be overcome only if the judge is convinced that such evidence is unavailable (8 U.S.C. § 1252(b)(4)).

Restricting illegal immigrants or legal immigrants who are unable to prove their legal status, or lack social security numbers, from obtaining drivers' licenses may keep them from obtaining liability insurance and from working, causing many immigrants and foreign nationals to lose their jobs or to travel internationally in order to renew their driver's license. Furthermore, for visitors on J-1 and H1B visas, the fact that visas may expire before their legal stay is over (this happens due to the fact that J-1 visas are issued with a one-year expiration date but visitors are allowed to stay for their "duration of status" as long as they have a valid contract) can make the process of renewing a driver's license extremely complex and, as mentioned above, force legal foreign citizens to travel abroad only to renew a visa which would not need to be renewed if it weren't for the need to renew one's driver's license. Although the new law does allow states to offer "not for federal ID" licenses in these cases, and that some states (e.g., Utah and Tennessee) have already started issuing such "driving privileges certificates/cards" in lieu of regular drivers' licenses, allowing such applicants to be tested and licensed to drive and obtain liability insurance, the majority of U.S. states do not plan to offer "not for federal ID" licenses. In October 2007, then-governor of New York Eliot Spitzer announced that the state will adopt a similar "multi-tiered" licensing scheme in which the state will issue three different kinds of driver licenses, two of which comply with the Real ID security requirements and one which will be marked as "not for federal ID" purposes.[43] However, following a political outcry, Spitzer withdrew his proposal to issue licenses to those unable to prove legal residence.[44]

Waiving laws that interfere with construction of border barriers

An earlier law (Section 102 of Pub.L. 104–208 which is now part of 8 U.S.C. § 1103) provided for improvements to physical barriers at the borders of the United States.

Subsection (a) of the law read as follows: "The Attorney General, in consultation with the Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization, shall take such actions as may be necessary to install additional physical barriers and roads (including the removal of obstacles to detection of illegal entrants) in the vicinity of the United States border to deter illegal crossings in areas of high illegal entry into the United States."

Subsection (b) orders the Attorney General to commence work on specified improvements to a 14-mile section of the existing border fence near San Diego, and allocates funds for the project.

Subsection (c) provides for waivers of laws that interfere with the work described in subsections (a) and (b), including the National Environmental Policy Act. Prior to the Real ID Act, this subsection allowed waivers of only two specific federal environmental laws.

The Real ID Act amends the language of subsection (c) to make the following changes:

- Allows waivers of any and all laws "necessary to ensure expeditious construction of the barriers and roads under this section".

- Gives this waiver authority to the Secretary of Homeland Security (rather than the Attorney General). Waivers are made at his sole discretion.

- Restricts court review of waiver decisions: "The district courts of the United States shall have exclusive jurisdiction to hear all causes or claims arising from any action undertaken, or any decision made, by the Secretary of Homeland Security pursuant to paragraph (1). A cause of action or claim may only be brought alleging a violation of the Constitution of the United States. The court shall not have jurisdiction to hear any claim not specified in this subparagraph." Claims are barred unless filed within 60 days, and cases may be appealed "only upon petition for a writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court".

Application for asylum and deportation of aliens for terrorist activity

The Real ID Act introduces strict laws governing applications for asylum and deportation of aliens for terrorist activity. However, at the same time, it makes two minor changes to U.S. immigration law:

- Elimination of the 10,000 annual limit for previously approved asylees to adjust to permanent legal residence.

- Usage of 50,000 unused employment-based visas from 2003. This was a compromise between proponents who had earlier tried to include all employment visas which went unused between 2001 and 2004, and immigration restrictionists. They were used, mostly in fiscal year 2006, for Schedule A workers newly arrived mainly from the Philippines and India, rather than for adjustments of status cases like the American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act.

The deportation of aliens for terrorist activities is governed by the following provisions:

Section 212(a)(3)(B): Terrorist activities

The INA (Immigration & Nationality Act) defines "terrorist activity" to mean any activity which is unlawful under the laws of the place where it is committed (or which, if committed in the United States, would be unlawful under the laws of the United States or any State) and which involves any of the following:

- (I) The hijacking or sabotage of any conveyance (including an aircraft, vessel, or vehicle).

- (II) The seizing or detaining, and threatening to kill, injure, or continue to detain, another individual in order to compel a third person (including a governmental organization) to do or abstain from doing any act as an explicit or implicit condition for the release of the individual seized or detained.

- (III) A violent attack upon an internationally protected person (as defined in Section 1116(b)(4) of Title 18, United States Code) or upon the liberty of such a person.

- (IV) An assassination.

- (V) The use of any:

- (a) biological agent, chemical agent, or nuclear weapon or device.

- (b) explosive, firearm, or other weapon or dangerous device (other than for mere personal monetary gain), with intent to endanger, directly or indirectly, the safety of one or more individuals or to cause substantial damage to property.

- (VI) A threat, attempt, or conspiracy to do any of the foregoing.

Other pertinent portions of Section 212(a)(3)(B) are set forth below:

"Engage in terrorist activity" defined

As used in this chapter (Chapter 8 of the INA), the term, "engage in terrorist activity" means in an individual capacity or as a member of an organization:

- to commit or to incite to commit, under circumstances indicating an intention to cause death or serious bodily injury, a terrorist activity;

- to gather information on potential targets for terrorist activity;

- to prepare or plan a terrorist activity;

- to solicit funds or other things of value for:

- (aa) a terrorist activity;

- (bb) a terrorist organization described in Clause (vi)(I) or (vi)(II);

- (cc) a terrorist organization described in Clause (vi)(III), unless the solicitor can demonstrate that he did not know, and should not reasonably have known, that the solicitation would further the organization's terrorist activity;

- to solicit any individual:

- (aa) to engage in conduct otherwise described in this clause;

- (bb) for membership in terrorist organization described in Clause (vi)(I) or (vi)(II); or

- (cc) for membership in a terrorist organization described in Clause (vi)(III), unless the solicitor can demonstrate that he did not know, and should not reasonably have known, that the solicitation would further the organization's terrorist activity; or

- to commit an act that the actor knows, or reasonably should know, affords material support, including a safe house, transportation, communications, funds, transfer of funds or other material financial benefit, false documentation or identification, weapons (including chemical, biological, or radiological weapons), explosives, or training:

- (aa) for the commission of a terrorist activity;

- (bb) to any individual who the actor knows, or reasonably should know, has committed or plans to commit a terrorist activity;

- (cc) to a terrorist organization described in Clause (vi)(I) or (vi)(II); or

- (dd) to a terrorist organization described in Clause (vi)(III), unless the actor can demonstrate that he did not know, and should not reasonably have known, that the act would further the organization's terrorist activity.

This clause shall not apply to any material support the alien afforded to an organization or individual that has committed terrorist activity, if the Secretary of State, after consultation with the Attorney General, or the Attorney General, after consultation with the Secretary of State, concludes in his sole unreviewable discretion, that that this clause should not apply."

"Representative" defined

As used in this paragraph, the term, "representative" includes an officer, official, or spokesman of an organization, and any person who directs, counsels, commands, or induces an organization or its members to engage in terrorist activity.

"Terrorist organization" defined

As used in Clause (i)(VI) and Clause (iv), the term 'foreign terrorist organization' means an organization:

- designated under Section 219 (8 U.S.C. § 1189);

- otherwise designated, upon publication in the Federal Register, by the Secretary of State in consultation with or upon the request of the Attorney General, as a terrorist organization, after finding that the organization engages in the activities described in Subclause (I), (II), or (III) of Clause (iv), or that the organization provides material support to further terrorist activity; or

- that is a group of two or more individuals, whether organized or not, which engages in the activities described in Subclause (I), (II), or (III) of Clause (iv).

Section 140(d)(2) of the "Foreign Relations Authorization Act", Fiscal Years 1988 and 1989 defines "terrorism" as "premeditated, politically motivated violence, perpetrated against noncombatant targets by subnational groups or clandestine agents".

Other provisions

Delivery bonds

The Real ID Act introduces complex rules covering "delivery bonds". These resemble bail bonds, but are to be required for aliens that have been released pending hearings.

Miscellaneous provisions

The remaining sections of the Real ID Act allocate funding for some reports and pilot projects related to border security, and change visa limits for temporary workers, nurses, and Australians.

Under the Real ID Act, nationals of Australia are eligible to receive a special E-3 visa. This provision was the result of negotiations between the two countries that also led to the Australia-United States Free Trade Agreement which came into force on January 1, 2005.

On December 17, 2018, H.R. 3398 amended the Real ID Act of 2005 to remove an outdated reference to the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (terminated in 1994) and clarify that citizens of its successor Freely Associated States (Marshall Islands, Micronesia and Palau) are eligible for drivers' licenses and ID cards when admitted to the U.S.[45]

Effects

Starting October 1, 2021 "every air traveler will need a REAL ID-compliant license, or another acceptable form of identification (such as a U.S. passport, U.S. passport card, U.S. military card, or DHS trusted traveler card, e.g. Global Entry, NEXUS, SENTRI, FAST) for domestic air travel."[7][8][6]

State adoption and non-compliance

Portions of the Real ID Act pertaining to states were scheduled to take effect on May 11, 2008, three years after the law passed, but the deadline had been extended to December 31, 2009.[46] On January 11, 2008, it was announced the deadline had been extended again, until 2011, in hopes of gaining more support from states.[18] On March 5, 2011, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) postponed the effective date of the Real ID Act until January 15, 2013, a move that avoided causing tremendous disruptions to air travel.[47]

The DHS began certifying states as compliant in 2012.[21] Adoption slowed after 2013 but increased significantly in 2018 and 2019, as the final phase of implementation approached and states were faced with potential air travel restrictions for their residents. As of April 2020, 52 states and territories have been certified as compliant, 2 have been granted extensions, and 2 are under review.[9]

| 2012[48] | 2013[49] | 2014[21][50] | 2018[51] | 2019[52] | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 2016[53] | Granted extension | ||||

| 2017[54] | Under review | ||||

The Real ID Act requires states and territories to share their ID databases with each other, but this requirement is not included in the DHS certification criteria.[36] The system used to share ID databases was implemented in 2015. As of April 2020, 27 states participate in this system.[55]

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

State adoption timeline

On January 25, 2007, a Resolution passed overwhelmingly in the Maine Legislature that refuses to implement the Real ID Act in that state and calls on Congress to repeal the law. Many Maine lawmakers believe the law does more harm than good, it would be a bureaucratic nightmare to enforce, it threatens individual privacy, it makes citizens increasingly vulnerable to ID theft, and it would cost Maine taxpayers at least $185 million in five years because of the massive unfunded federal mandates on all the states. The Resolution vote in the Maine House was 137–4 and in the Maine Senate unanimous, 34–0.[56]

On February 16, 2007, Utah unanimously passed a resolution that opposes the Real ID Act.[57] The resolution states that Real ID is "in opposition to the Jeffersonian principles of individual liberty, free markets, and limited government". It further states that "the use of identification-based security cannot be justified as part of a 'layered' security system if the costs of the identification 'layer'—in dollars, lost privacy, and lost liberty—are greater than the security identification provides":

—the 'common machine-readable technology' required by the Real ID Act would convert state-issued driver licenses and identification cards into tracking devices, allowing computers to note and record people's whereabouts each time they are identified.

—the requirement that states maintain databases of information about their citizens and residents and then share this personal information with all other states will expose every state to the information security weaknesses of every other state and threaten the privacy of every American.

—the REAL ID Act wrongly coerces states into doing the federal government's bidding by threatening to refuse noncomplying states' citizens the privileges and immunities enjoyed by other states' citizens.

Alaska,[58][59] Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and Washington State have joined Maine and Utah in passing legislation opposing Real ID.[60][61][62][63][64][65][66]

Similar resolutions are pending in Kentucky, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Washington, D.C., West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming.[67]

Other states have moved aggressively to upgrade their IDs since 9/11, and still others have staked decidedly pro-Real ID positions, such as North Carolina.[68] Some states, such as Illinois, are working to comply with Real ID despite their legislatures passing non-binding resolutions opposing it.[69] In announcing the new regulations, Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff cited Alabama, California, and North Dakota as examples of states that had made progress in complying with Real ID.[70]

On July 7, 2008, Puerto Rico's Governor Aníbal Acevedo Vilá announced that all 15 Puerto Rico Department of Transportation and Public Works Driver's Services Centers will implement a new system complying with the Real-ID Act.[71]

As of January 29, 2008, the Department of Homeland Security has announced $79.8 million in grant monies[72] to assist states with Real ID implementation, and set an application deadline of March 7, 2008.

On April 16, 2009, the Missouri House of Representatives passed the anti Real ID bill HB 361 to repeal section 302.171, RSMo, and to enact in lieu thereof two new sections relating to noncompliance with the federal Real ID Act of 2005 sponsored by Representative Jim Guest by a vote of 83 Ayes 69 Noes and 3 Present. On May 13, 2009 the Missouri Senate unanimously passed HB 361, 43 Ayes 0 Noes. Missouri Governor Jay Nixon signed this bill into law on July 13, 2009.[73] This was later repealed in 2017.[74][75] Alaska repealed its anti-Real-ID law in 2017.[76]

For the 2012 Florida Legislative Session, the anti-Real ID bill HB 109[77] and its Senate companion S 220 will be heard.[78] Named the Florida Driver's License Citizen Protection Act,[79] it would require discontinuation of several of the federally mandated provisions of Real ID and destruction of citizen's documents that had been scanned into the government database. That bill died in Transportation and Highway Safety Subcommittee on March 9, 2012.[80]

New Jersey planned to begin issuing Real ID compliant drivers' licenses and non-driver ID cards beginning May 7, 2012,[81] but was forestalled by a temporary restraining order issued on May 4, 2012 on motion of the ACLU.[82] On October 5, 2012, the state subsequently agreed to drop its Real ID compliant license plan, settling the lawsuit brought by the ACLU.[83]

On July 1, 2012, Georgia began issuing Real ID compliant drivers' licenses and non-driver ID cards.[84] The increase in items needed to show in order to receive a license caused wait times to reach up to five hours.[85]

Although Hawaii had expressed opposition to some portions of the Real ID Act, it began requiring proof of legal presence in March 2012.[86] Hawaii's updated drivers' licenses and non-driver ID cards were deemed fully compliant by the Department of Homeland Security in September 2013.[87]

On November 12, 2014, Nevada began offering Real ID compliant drivers' licenses to residents. Nevadans have a choice of a Real ID compliant card or a standard card with the heading "Not for Federal Official Use".[88]

On April 14, 2015, Arizona governor Doug Ducey signed a bill allowing the state to begin the process of making Arizona drivers' licenses Real ID compliant.[89] Work on creating the drivers' licenses has already begun, however the Arizona Department of Transportation has requested an extension on the implementation so that residents can still use current ID past the January 2016 deadline to board a commercial flight and implement Real ID when the state is ready.[90]

On March 8, 2016, the incumbent governor of New Mexico, Susana Martinez, signed House Bill 99 into law, hence bringing New Mexico into Real ID compliance.[91]

The New Mexico MVD began issuing Real ID compliant drivers' licenses and identification cards beginning November 14, 2016.[92]

On March 1, 2017, Oklahoma Governor Mary Fallin signed HB 1845 as the first bill signed in Oklahoma's 2017 legislative session, bringing the state into compliance with the Real ID Act.[93]

On May 18, 2017, Minnesota Governor Mark Dayton signed legislation to bring Minnesota into compliance with the federal Real ID Act by October 2018.[94]

Starting January 22, 2018, the California DMV started providing federal compliant Real ID driver licenses and ID cards as an option to customers .[95] However, on December 24, the Department of Homeland Security has notified the California DMV that their Real ID driver licenses are not Real ID Compliant. This is because the California DMV has been requesting one “Proof of Residency” document as opposed to the minimum two as defined under Federal Law. The California DMV responded stating they will begin asking for two Residency Documents beginning in April 2019.

Any Real ID Driver License or Identification Card issued before April 2019 will still be valid, however, letters were sent out to persons who only submitted one proof of residency to get their Real ID. The letter asked for the person to check a box to verify that the mailing address of record was still valid and to return the letter in a provided envelope. Otherwise, the person was directed to return the letter with two documents which demonstrate the correct address, and to submit a separate address correction.[96] The Massachusetts RMV also started this option on March 26, 2018,[97] and the Ohio BMV on July 2, 2018.[98][99]

On March 25, 2019 Missouri became the 47th state to implement and comply with the Real ID Act.[100]

Controversy and opposition

The Bush administration's Real ID Act was strongly supported by the conservative Heritage Foundation and by many opponents of illegal immigration.[101] However, it faced criticism from across the political spectrum, including from libertarian groups, like the Cato Institute;[102] immigrant advocacy groups; human and civil rights organizations, like the ACLU; Christian advocacy groups, such as the American Center for Law & Justice (ACLJ);[103] privacy advocacy groups, like the 511 campaign; state-level opposition groups, such as North Carolinians Against Real ID[104] and government accountability groups in Florida;[105] labor groups, like AFL-CIO; People for the American Way; consumer and patient protection groups; some gun rights groups, such as Gun Owners of America; many state lawmakers, state legislatures, and governors; The Constitution Party;[101][106] and the editorial page of the Wall Street Journal, among others.

Highlighting the broad diversity of the coalition opposing Title II of the Real ID Act, the American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ), founded by evangelical Christian Pat Robertson, participated in a joint press conference with the ACLU in 2008.[107]

Among the 2008 presidential candidates, John McCain strongly supported the Real ID Act, but Hillary Clinton called for it to be reviewed, Barack Obama and Ron Paul flatly opposed it, and Mike Huckabee called it "a huge mistake."[108][109] The subsequent Obama administration opposed it.

The Real ID Act causes special concerns for transgender people.[110] In 2008, Cindy Southworth, technology project director for the National Network to End Domestic Violence, noted a "conundrum" in the mission "to identify people who are dangerous, such as terrorists, and at the same time, to keep "everyday citizens and victims safe."[111] The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence has also voiced concern about Real ID.[112]

Florida Libertarian Party chair Adrian Wyllie drove without carrying a driver's license in 2011 in protest of the Real ID Act. After being ticketed, Wyllie argued in court that Florida's identification laws violated his privacy rights; this claim was rejected by a judge.[113]

Congressional passage procedure controversy

The original Real ID Act, H. R. 418, was approved by the House on February 10, 2005, by a vote of 261–161. At the insistence of the Real ID Act sponsor and then House Judiciary Committee Chair F. James Sensenbrenner (Republican, Wisconsin), the Real ID Act was subsequently attached by the House Republican leadership as a rider to H.R. 1268, a bill dealing with emergency appropriations for the Iraq War and with the tsunami relief funding. H.R. 1268 was widely regarded as a "must-pass" legislation. The original version of H.R. 1268 was passed by the Senate on April 21, 2005, and did not include the Real ID Act. However, the Real ID Act was inserted in the conference report on H.R. 1268 that was then passed by the House on May 5, 2005, by a 368–58 vote and was unanimously passed by the Senate on May 10, 2005.[114] The Senate never discussed or voted on the Real ID Act specifically and no Senate committee hearings were conducted on the Real ID Act prior to its passage.[115] Critics charged that this procedure was undemocratic and that the bill's proponents avoided a substantive debate on a far-reaching piece of legislation by attaching it to a "must-pass" bill.[115][116][117][118]

A May 3, 2005, statement by the American Immigration Lawyers Association said: "Because Congress held no hearings or meaningful debate on the legislation and amended it to a must-pass spending bill, the Real ID Act did not receive the scrutiny necessary for most measures, and most certainly not the level required for a measure of this importance and impact. Consistent with the lack of debate and discussion, conference negotiations also were held behind closed doors, with Democrats prevented from participating."[119]

National ID card controversy

There is disagreement about whether the Real ID Act institutes a "national identification card" system.[120] The new law only sets forth national standards, but leaves the issuance of cards and the maintenance of databases in state hands; therefore, the Department of Homeland Security claims it is not a "national ID" system.[121] Web sites such as no2realid.org, unrealid.com, and realnightmare.org argue that this is a trivial distinction, and that the new cards are in fact national ID cards, thanks to the uniform national standards created by the AAMVA and (especially) the linked databases, and by the fact that such identification is mandatory if people wish to travel out of the United States.

Many advocacy groups and individual opponents of the Real ID Act believe that having a Real ID-compliant license may become a requirement for various basic tasks. Thus a January 2008 statement by ACLU of Maryland says: "The law places no limits on potential required uses for Real IDs. In time, Real IDs could be required to vote, collect a Social Security check, access Medicaid, open a bank account, go to an Orioles game, or buy a gun. The private sector could begin mandating a Real ID to perform countless commercial and financial activities, such as renting a DVD or buying car insurance. Real ID cards would become a necessity, making them de facto national IDs". However, in order to perform some tasks, government-issued identification is already required (e.g., two forms of ID – usually a driver's license, passport, or Social Security card – are required by the Patriot Act in order to open a bank account).[122]

Constitutionality

Some critics claim that the Real ID Act violates the Tenth Amendment to the United States Constitution as a federal legislation in an area that, under the terms of the Tenth Amendment, is the province of the states. Thus, Anthony Romero, the executive director of ACLU, stated: "Real ID is an unfunded mandate that violates the Constitution's 10th Amendment on state powers, destroys states' dual sovereignty and consolidates every American's private information, leaving all of us far more vulnerable to identity thieves".[123]

Former Republican U.S. Representative Bob Barr wrote in a February 2008 article: "A person not possessing a Real ID Act-compliant identification card could not enter any federal building, or an office of his or her congressman or senator or the U.S. Capitol. This effectively denies that person their fundamental rights to assembly and to petition the government as guaranteed in the First Amendment".[124]

The DHS final rule regarding implementation of the Real ID Act discusses a number of constitutional concerns raised by the commenters on the proposed version of this rule.[19] The DHS rule explicitly rejects the assertion that the implementation of the Real ID Act will lead to violations of the citizens' individual constitutional rights (page 5284 of the DHS rule in the Federal Register). In relation to the Tenth Amendment argument about violation of states' constitutional rights, the DHS rule acknowledges that these concerns have been raised by a number of individual commenters and in the comments by some states. The DHS rule does not attempt to rebuff the Tenth Amendment argument directly, but says that the DHS is acting in accordance with the authority granted to it by the Real ID Act and that DHS has been and will be working closely with the states on the implementation of the Real ID Act (pages 5284 and 5317 of the DHS final rule in the Federal Register).

On November 1, 2007, attorneys for Defenders of Wildlife and the Sierra Club filed an amended complaint in U.S. District Court challenging the 2005 Real ID Act. The amended complaint alleges that this unprecedented authority violates the fundamental separation of powers principles enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. On December 18, 2007, Judge Ellen Segal Huvelle rejected the challenge.[125][126]

On March 17, 2008, attorneys for Defenders of Wildlife and the Sierra Club filed a Petition for a Writ of Certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court to hear its "constitutional challenge to the Secretary's decision waiving nineteen federal laws, and all state and local legal requirements related to them, in connection with the construction of a barrier along a portion of the border with Mexico".[127][128] They question whether the preclusion of judicial review amounts to an unconstitutional delegation of legislative power and whether the "grant of waiver authority violates Article I's requirement that a duly-enacted law may be repealed only by legislation approved by both Houses of Congress and presented to the President".[127] On April 17, 2008, numerous amicus briefs "supporting the petition were filed on behalf 14 members of Congress, a diverse coalition of conservation, religious and Native American organizations, and 28 law professors and constitutional scholars".[129][130][131]

Asylum and deportation controversy

Many immigrant and civil rights advocates feel that the changes related to evidentiary standards and the immigration officers' discretion in asylum cases, contained in the Real ID Act, would prevent many legitimate asylum seekers from obtaining asylum.[132][133] Thus a 2005 article in LCCR-sponsored Civil Rights Monitor stated, "The bill also contained changes to asylum standards, which according to LCCR, would prevent many legitimate asylum seekers from obtaining safe haven in the United States. These changes gave immigration officials broad discretion to demand certain evidence to support an asylum claim, with little regard to whether the evidence can realistically be obtained; as well as the discretion to deny claims based on such subjective factors as "demeanor". Critics said the reason for putting such asylum restrictions into what was being sold as an anti terrorism bill was unclear, given that suspected terrorists are already barred from obtaining asylum or any other immigration benefit".[132]

Similarly, some immigration and human rights advocacy groups maintain that the Real ID Act provides an overly broad definition of "terrorist activity" that will prevent some deserving categories of applicants from gaining asylum or refugee status in the United States.[134] A November 2007 report by Human Rights Watch raises this criticism specifically in relation to former child soldiers who have been forcibly and illegally recruited to participate in an armed group.[135]

Privacy

Many privacy rights advocates charge that by creating a national system electronically storing vast amounts of detailed personal data about individuals, the Real ID Act increases the chance of such data being stolen and thus raises the risk of identity theft.[136][137][138][139] The Bush administration, in the DHS final rule[19] regarding the Real ID Act implementation, counters that the security precautions regarding handling sensitive personal data and hiring DMV workers, that are specified in the Real ID Act and in the rule, provide sufficient protections against unauthorized use and theft of such personal data (pages 5281–5283 of the DHS final rule in the Federal Register).

Another privacy concern raised by privacy advocates such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation is that the implementation of the Real ID Act will make it substantially easier for the government to track numerous activities of Americans and conduct surveillance.[140][141]

Supporters of the Real ID Act, such as a conservative think-tank The Heritage Foundation, dismiss this criticism under the grounds that states will be permitted (by law) to share data only when validating someone's identity.[140]

The Data Privacy and Integrity Advisory Committee, which was established to advise the Department of Homeland Security on privacy-related issues, released a statement regarding the Department of Homeland Security's proposed rules for the standardization of state driver licenses on May 7, 2007.[142] The committee stated that "Given that these issues have not received adequate consideration, the Committee feels it is important that the following comments do not constitute an endorsement of REAL ID or the regulations as workable or appropriate", and "The issues pose serious risks to an individual's privacy and, without amelioration, could undermine the stated goals of the REAL ID Act".

See also

References

- Virginia Receives Extension On Real ID Requirements from a March 31, 2008 newsplex.com article

- "REAL ID Enforcement in Brief" (PDF). U.S. Department of Homeland Security. December 20, 2013.

- Pub.L. 109–13

- "Public Law 109-13 Title II Sec. 201 (3)". Government Printing Office. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- "Countdown to REAL ID". National Conference of State Legislatures. December 23, 2013.

- Acting Secretary Chad Wolf Statement on the REAL ID Enforcement Deadline, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, March 26, 2020.

- https://www.tsa.gov/travel/security-screening/identification

- "Statement by Sec J. Johnson". Homeland Security.

- "REAL ID". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. March 27, 2020.

- "261-161-11 House.gov".

- "HR 1268: Making emergency supplemental appropriations".

- "U.S. Senate: U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes 109th Congress - 1st Session". www.senate.gov.

- S. 717: Identification Security Enhancement Act of 2007 GovTrack.us. Access date February 17, 2008

- H.R. 1117: REAL ID Repeal and Identification Security Enhancement Act of 2007 GovTrack.us. Access date February 17, 2008

- S. 563: A bill to extend the deadline by which State identification documents shall comply with certain minimum standards and for other purposes GovTrack.us. Access date February 18, 2008

- "REAL ID". Department of Homeland Security. July 25, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- "States get More Time on National ID Law", Los Angeles Times, January 12, 2008.

- "New rules on licenses pit states against feds".

- "DHS REAL ID Final Rule, January 11, 2008" (PDF).

- "Biometric Bits - Home Page". www.biometricbits.com.

- "REAL ID Frequently Asked Questions". Department of Homeland Security. April 10, 2020. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- "States get 'Real ID' extensions - USATODAY.com". www.usatoday.com.

- Obama will inherit a real mess on Real ID Archived March 28, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "REAL ID Repeal and Identification Security Enhancement Act of 2007 (2007 - H.R. 1117)". GovTrack.us.

- "Real ID Public FAQs". December 29, 2013.

- Intelligence Reform and Terrorism Prevention Act of 2004 , ww.govtrack.us. Accessed February 19, 2008

- "NCSI.org" (PDF).

- "Transportation Security Administration: Information for Travelers".

- http://epic.org/privacy/id_cards/nprm_030107.pdf p. 94

- https://www.dhs.gov/xnews/releases/pr_1196872524298.shtm

- "Real IDs to Become Real in 2010". Betanews.com.

- "Real ID Act of 2005, full text".

- "Privacy Impact Assessment for the REAL ID Act" https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/privacy_pia_realid_1.pdf

- "How the REAL-ID Act is creating a national ID database". The Identity Project. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- "Verification of Legal Status (VLS)" https://www.aamva.org/VLS/

- Harper, Jim. "What Is Real REAL ID Compliance?". Cato Institute. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- http://www.aamva.org/KnowledgeCenter/Driver/Compacts/History+of+the+DLA.htm

- http://americanpolicy.org/privacy-rights/real-id-connecting-the-dots-to-an-international-id.html/

- https://www.eff.org/files/filenode/realid/real_id_final_rule_part1_2008-01-11.pdf

- See here for the full information

- http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-12-29/pdf/2014-30082.pdf

- Homeland Security bows to Real ID outcry. CBS News, March 5, 2011. Accessed December 26, 2011

- Hakim, Danny (October 28, 2007). "Spitzer Tries New Tack on Immigrant Licenses". The New York Times.

- Confessore, Nicholas (November 14, 2007). "Spitzer Drops Bid to Offer Licenses More Widely". The New York Times.

- H.R. 3398 (115th): Real ID Act Modification for Freely Associated States Act, Govtrack.

- Gaouette, Nicole (March 2, 2007). "National ID requirements postponed under criticism". LA Times.

- McCullagh, Declan. "Homeland Security bows to Real ID outcr". CNET News. Retrieved May 30, 2012.

- DHS determines 13 states meet Real ID standards, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, December 20, 2012.

- DHS releases phased enforcement schedule for Real ID, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, December 20, 2013.

- "Current status of states/territories". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on January 7, 2016.

- "Real ID". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on December 31, 2018.

- "Real ID". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019.

- "Current status of states/territories". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016.

- "Real ID". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on December 31, 2017.

- "State to State (S2S) Verification Services". American Association of Motor Vehicle Administrators. March 19, 2020.

- "An Act To Prohibit Maine from Participating in the Federal REAL ID Act of 2005" (PDF). Maine Legislature.

- "Utah Legislature HR0002". Utah Legislature.

- "Alaska State Legislature". www.akleg.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- "Alaska State Legislature". www.akleg.gov. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- 'Washington Becomes Fourth State to Oppose REAL ID', ACLU, April 5, 2007. Accessed July 23, 2007.

- "Congress rethinks the Real ID Act", CNET News, May 8, 2007. Accessed May 19, 2016.

- 'National ID Cards and REAL ID Act', Electronic Privacy Information Center. Accessed July 23, 2007.

- 'Gov signs law rejecting Real ID act', Billings Gazette, April 17, 2007. Accessed July 23, 2007.

- 'Bill Information for SJR0248' Tennessee State Legislature. Accessed August 8, 2007.

- Napolitano: Real ID a no-go in Arizona

- "Real ID Nullification Legislation". Tenth Amendment Center. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- "Status of Anti-Real ID Legislation in the States", ACLU, Accessed November 4, 2007.

- "Remarks of the North Carolina Department of Motor Vehicles Commissioner to the North Carolina Joint Legislative Committee on Transportation Oversight, December 12, 2006". National Conference of State Legislatures. December 12, 2006. Archived from the original on June 16, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- "New Illinois licenses needed by 2010 for airport security". Illinois Pantagraph. January 27, 2008.

- "News Release". DHS.gov.

- "Press statement". La Fortaleza. July 7, 2008.

- "Press release: DHS Increases Funding For REAL ID Grant Program and Extends Applications Deadline, January 29, 2008". DHS.

- "Bill Actions". House.mo.gov.

- By. "Greitens signs Real ID legislation, putting Missouri in compliance with federal law". kansascity. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- "Missouri House of Representatives - Bill Information for HB151". house.mo.gov. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- reports, Staff and Wire. "UPDATE: Gov. Walker signs REAL ID bill into law". www.ktuu.com. Retrieved June 10, 2019.

- "HB 109 - Issuance and Renewal of Drivers' Licenses and Identification Cards". Florida House of Representatives.

- "Senate Bill 220". The Florida Senate. 2012.

- "Floridians Against REAL ID: Florida Driver's License Citizen Protection Act as of September 19, 2011" (PDF). Liberty2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2012.

- "House Bill 109". The Florida Senate. 2012.

- "TRU-ID page". =NJ Motor Vehicle Commission.

- "ACLU-NJ Wins Round Two of Real ID Battle". ACLU.

- "State Settles ACLU-NJ Lawsuit by Agreeing to Drop TRU-ID Program". ACLU.

- "Identification Requirements". Georgia Department Of Driver Services.

- EndPlay (July 5, 2012). "New law causing hours-long wait at DDS offices". WSBTV.

- "New driver's license law sure to confuse, slow down process". Hawaii News Now. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- "Hawaii Fully Compliant with REAL ID Standards for Drivers' Licenses, State Identification Cards". Hawaii.gov. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- "DMV to offer Real ID drivers' licenses". Dmvnv.com.

- "Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey signs Real ID bill". KTAR-FM. April 14, 2015.

- "Secure Arizona driver's license takes step toward reality". AZCentral.

- "Legislation". New Mexico Legislature.

- "Drivers' Licenses/IDs". Mvd.newmexico.gov.

- McCleland, Jacob. "Fallin Signs REAL ID Compliance Bill Into Law". KGOU.

- "With new law, Minnesota becomes the last state to comply with federal Real ID Act". Minnesota Post.

- https://www.dmv.ca.gov/portal/dmv/detail/realid

- "Second Residency FAQs". California Department of Motor Vehicles. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- Real ID real answers, Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles.

- "State of Ohio BMV - Ohio's New Driver License and Identification Card". www.bmv.ohio.gov. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- "Making Ohio Driver Licenses and Identification Cards More Secure - Fact Sheet" (PDF). Ohio Bureau of Motor Vehicles. Retrieved March 6, 2018.

- "Real ID Information - Motor Vehicle Section". dor.mo.gov. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

- "Congress rethinks the Real ID Act". CNET. May 8, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- ccpafl (May 18, 2011). "Florida LP Chairman Adrian Wyllie surrenders license in protest of REAL ID act" – via YouTube.

- http://www.repobrien.com/NewsItem.aspx?NewsID=3724

- "North Carolinians Against Real ID website".

- "Floridians Against REAL ID website". Archived from the original on July 6, 2011.

- The Privacy Coalition Accessed February 17, 2008

- Steve Meyer (February 10, 2009). "Real ID Exposed at National Press Club with Mark Lerner, Host" – via YouTube.

- McCullagh, Declan. "In '08 presidential race, who's the most tech-friendly?", CNET, February 5, 2008. Accessed February 17, 2008

- "Mike Huckabee: The RCP Interview". Real Clear Politics. September 25, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- Beauchamp, Toby (2009). "Artful Concealment and Strategic Visibility: Transgender Bodies & U.S. State Surveillance After 9/11". Surveillance and Society. 6 (4): 356–366. doi:10.24908/ss.v6i4.3267.

- Broache, Anne (February 8, 2008). "Real ID worries domestic violence groups". CNET. Retrieved November 5, 2019.

- http://www.ncadv.org/publicpolicy/REALIDLaws.php

-

- Jacob Carpenter, Judge to former gubernatorial candidate: Good try, no dice, Naples Daily News (March 2, 2015).

- Curtis Krueger, Libertarian gets ticketed on purpose to make argument in court Libertarian gets ticketed on purpose to make argument in court, St. Petersburg Times (September 7, 2011).

- H.R. 1268 Legislative History, thomas.loc.gov

- Statement of Senator Patrick Leahy May 8, 2007. Accessed February 18, 2008

- "No Real Debate for Real ID". Wired. May 10, 2005. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- "Immigrants' Rights Update, Vol. 19, Issue 2". National Immigration Law Center. March 31, 2005. Archived from the original on October 23, 2005. Retrieved July 7, 2008.

- Real ID Act Attached to "Must-Pass" Spending Bill Imposes Anti-Immigrant Measures Democracy Now! April 29, 2005. Accessed February 17, 2008

- AILA Statement on REAL ID May 3, 2005

- McCullagh, Declan, "FAQ: How Real ID will affect you", CNET, May 6, 2005. Accessed May 5, 2007

- DHS: REAL ID Proposed Guidelines: Questions & Answers Archived March 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "ACLU Of Maryland Blasts New Real ID Regulations", ACLU, January 15, 2008. Accessed February 17, 2008

- "Opposing view: Repeal Real ID". USA Today. March 6, 2007. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- "Real ID Act a Real Intrusion on Rights, Privacy". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. February 6, 2008. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- "Border Fence Construction: San Pedro Riparian NCA – Defenders of Wildlife".

- "Conservation Groups Challenge Chertoff's Waiver Power as Unconstitutional". November 1, 2007.

- Andrew J. Pincus; Charles A. Rothfeld, Robert Dreher, Brian Segee, Dan Kahan, Terri-Lei O'Malley (March 17, 2008). "Petition for Writ of Certiorari re: San Pedro Border Case" (PDF). p. 2. Retrieved September 16, 2008.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Joe Vickless; Oliver Bernstein (March 17, 2008). "U.S. Supreme Court Asked to Answer: Is Chertoff Above the Law?". Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Brian Segee; Cat Lazaroff (April 25, 2008). "Congress to hold field hearing on border wall". Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Wildlife and Border Policy". Defenders of Wildlife. April 2008. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- Joe Vickless; Cat Lazaroff (April 18, 2008). "Congressional, religious, cultural and academic leaders urge Supreme Court to hear challenge to border wall". Defenders of Wildlife. Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- "Anti-immigrant 'REAL ID' Act Becomes Law". Civil Rights Monitor. 15 (1). Fall–Winter 2005.

- "The 'REAL ID' Act Is a Really Bad Idea" (PDF). National Immigration Law Center. March 2005. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- "AIUSA Issue Brief: The REAL ID Act of 2005 and Its Negative Impact on Asylum Seekers". Amnesty International USA. March 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "United States of America: Compliance with the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. November 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "ACLU Scorecard on Final Real ID Regulations" (PDF). ACLU. January 17, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "Real ID Act Will Increase Exposure to ID Theft". Privacy Rights Clearinghouse. February 28, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "The Many Faces of the Real ID Act". PrivacyActivism. February 28, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "Real ID Act mostly helps identity thieves". The Mercury News. San Jose , Cal. May 19, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "Federal ID plan raises privacy concerns". CNN. August 16, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "Real ID. Threatening Your Privacy Through an Unfunded Government Mandate". Electronic Frontier Foundation. August 16, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Ryan Singel. May 7, 2007. "Homeland Security's Own Privacy Panel Declines to Endorse License Rules". Wired.

External links

- Actual proposed rules Search ID: DHS-2006-0030-0001 Click on "Docket ID" for commentary.

- From California DMV: REAL ID Act