Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act, is a federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The law abolished the National Origins Formula, which had been the basis of U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s. The act removed de facto discrimination against Southern and Eastern Europeans, Asians, and other non-Northwestern European ethnic groups from American immigration policy.

.svg.png) | |

| Long title | An Act to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | INA of 1965 |

| Nicknames | Hart–Celler |

| Enacted by | the 89th United States Congress |

| Effective | June 30, 1968 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | Pub.L. 89–236 |

| Statutes at Large | 79 Stat. 911 |

| Codification | |

| Acts amended | Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 |

| Titles amended | 8 U.S.C.: Aliens and Nationality |

| U.S.C. sections amended | 8 U.S.C. ch. 12 (§§ 1101, 1151–1157, 1181–1182, 1201, 1254–1255, 1259, 1322, 1351) |

| Legislative history | |

| |

Largely to restrict immigration from Asia, Southern Europe, and Eastern Europe, the Immigration Act of 1924 had permanently established the National Origins Formula as the basis of U.S. immigration policy. By limiting immigration of non-Northern Europeans, according to the U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian, the purpose of the 1924 Act was "to preserve the ideal of American [Northwestern European] homogeneity".[1] During the 1960s, at the height of the Civil Rights Movement, the National Origins Formula increasingly came under attack for being racially discriminatory. With the support of the Johnson administration, Senator Philip Hart and Congressman Emanuel Celler introduced a bill to repeal the formula. The bill received wide support from both northern Democratic and Republican members of Congress, but strong opposition from Southern Republicans and Democrats, the former mostly voting Nay or Not Voting. This issue served as an inter-party commonality amongst constituents and reflects the similar Congressional District and Representative voting patterns. President Johnson signed the Hart–Celler Act into law on October 3, 1965. In opening entry to the U.S. to immigrants other than Northwestern European and Germanic groups, the Act significantly altered immigration demographics in the U.S.[2] Some sources assert that this alteration was intentional,[5] others assert that it was unintentional.[7]

The Hart–Celler Act created a seven-category preference system that gives priority to relatives of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents, as well as to professionals and other individuals with specialized skills. The act maintained per-country and total immigration limits, but included a provision exempting immediate relatives of U.S. citizens from numerical restrictions. The act also set a numerical limit on immigration from the Western Hemisphere for the first time in U.S. history. Though proponents of the bill had argued that it would not have a major effect on the total level of immigration or the demographic mix of the United States, the act greatly increased the total number of immigrants coming to the United States, as well as the share of immigrants coming to the United States from Asia and Africa.

Background

The Hart–Celler Act of 1965 marked a radical break from U.S. immigration policies of the past. Since Congress restricted naturalized citizenship to "white persons" in 1790, laws restricted immigration from Asia and Africa, and gave preference to northern and western Europeans over southern and Eastern Europeans.[8][9] Limiting immigration of non-northern Europeans, according to the U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian, was "to preserve the ideal of American homogeneity".[1] German praise for America's institutional racism appeared throughout the early 1930s, influencing race-based citizenship laws, anti-miscegenation laws, and immigration laws.[10] Adolf Hitler wrote of his admiration of America's immigration laws in Mein Kampf, saying:

The American Union categorically refuses the immigration of physically unhealthy elements, and simply excludes the immigration of certain races.[11]

In the 1960s, the United States faced both foreign and domestic pressures to change its nation-based formula, which was regarded as a system that discriminated based on an individual's place of birth. Abroad, former military allies and new independent nations aimed to delegitimize discriminatory immigration, naturalization and regulations through international organizations like the United Nations.[12] In the United States, the national-based formula had been under scrutiny for a number of years. In 1952, President Truman had directed the Commission on Immigration and Naturalization to conduct an investigation and produce a report on the current immigration regulations. The report, Whom We Shall Welcome, served as the blueprint for the Hart–Celler Act.[13] At the height of the Civil Rights Movement the restrictive immigration laws were seen as an embarrassment.[2] President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1965 act into law at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, ending preferences for white immigrants dating to the 18th century.[8]

The immigration into the country of "sexual deviants", including homosexuals, was still prohibited under the legislation.[8] The INS continued to deny entry to homosexual prospective immigrants on the grounds that they were "mentally defective", or had a "constitutional psychopathic inferiority" until the Immigration Act of 1990 rescinded the provision discriminating against gay people.[14]

Provisions

The Hart–Celler Act amended the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952, or McCarran–Walter Act, while it upheld many provisions of the Immigration Act of 1924. It maintained per-country limits, which had been a feature of U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s, and it developed preference categories.[15]

- One of the main components aimed to abolish the national-origins quota. This meant that it eliminated national origin, race, and ancestry as basis for immigration.

- It created a seven-category preference system, which gave priority to relatives of U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents and to professionals and other individuals with specialized skills.

- Immediate relatives and "special immigrants" were not subject to numerical restrictions. Some of the "special immigrants" include ministers, former employees of the U.S. government, foreign medical graduates, among others.

- For the first time, immigration from the Western Hemisphere was limited.

- It added a labor certification requirement, which dictated that the Secretary of Labor needed to certify labor shortages.

- Refugees were given the seventh and last category preference with the possibility of adjusting their status. However, refugees could enter the United States through other means as well, like those seeking temporary asylum.

Wages under Foreign Certification

As per the rules under the Immigration and Nationality Act, U.S. organizations are permitted to employ foreign workers either temporarily or permanently to fulfill certain types of job requirements. The Employment and Training Administration under the U.S. Department of Labor is the body that usually provides certification to employers allowing them to hire foreign workers in order to bridge qualified and skilled labor gaps in certain business areas. Employers must confirm that they are unable to hire American workers willing to perform the job for wages paid by employers for the same occupation in the intended area of employment. However, some unique rules are applied to each category of visas. They are as follows:

- H-1B and H-1B1 Specialty (Professional) Workers should have a pay, as per the prevailing wage – an average wage that is paid to a person employed in the same occupation in the area of employment; or that the employer pays its workers the actual wage paid to people having similar skills and qualifications.

- H-2A Agricultural Workers should have the highest pay in accordance to the (a) Adverse Effect Wage Rate, (b) the present rate for a particular crop or area, or (c) the state or federal minimum wage. The law also stipulates requirements like employer-sponsored meals and transportation of the employees as well as restrictions on deducting from the workers' wages.

- H-2B Non-agricultural Workers should receive a pay that is in accordance with the prevailing wage (mean wage paid to a worker employed in a similar occupation in the concerned area of employment).

- D-1 Crewmembers (longshore work) should be paid the current wage (mean wage paid to a person employed in a similar occupation in the respective area of employment).

- Permanent Employment of Aliens should be employed after the employer has agreed to provide and pay as per the prevailing wage trends and that it should be decided on the basis of one of the many alternatives provisioned under the said Act. This rule has to be followed the moment the Alien has been granted with permanent residency or the Alien has been admitted in the United States so as to take the required position.[16]

Legislative history

The Hart–Celler Act was widely supported in Congress. Senator Philip Hart introduced the administration-backed immigration bill which was reported to the Senate Judiciary Committee's Immigration and Naturalization Subcommittee.[17] Representative Emanuel Celler introduced the bill in the United States House of Representatives, which voted 320 to 70 in favor of the act, while the United States Senate passed the bill by a vote of 76 to 18.[17] In the Senate, 52 Democrats voted yes, 14 no, and 1 abstained. Among Senate Republicans, 24 voted yes, 3 voted no, and 1 abstained.[18] In the House, 202 Democrats voted yes, 60 voted no and 12 abstained, 118 Republicans voted yes, 10 voted no and 11 abstained.[19] In total, 74% of Democrats and 85% of Republicans voted for passage of this bill. Most of the no votes were from the American South, which was then still strongly Democratic. During debate on the Senate floor, Senator Ted Kennedy, speaking of the effects of the Act, said, "our cities will not be flooded with a million immigrants annually. ... Secondly, the ethnic mix of this country will not be upset."[20]

Sen. Hiram Fong (R-HI) answered questions concerning the possible change in the United States' cultural pattern by an influx of Asians:

Asians represent six-tenths of 1 percent of the population of the United States ... with respect to Japan, we estimate that there will be a total for the first 5 years of some 5,391 ... the people from that part of the world will never reach 1 percent of the population ... Our cultural pattern will never be changed as far as America is concerned.

— U.S. Senate, Subcommittee on Immigration and Naturalization of the Committee on the Judiciary, Washington, D.C., Feb. 10, 1965, pp.71, 119.[21]

From 1966 to 1970, 19,399 immigrants came from Japan, more than three times Senator Fong's estimate. Immigration from Asia as a whole has totaled 5,627,576 from 1966 to 1993. 6.8% of the American population is currently of Asian birth or heritage.

Democrat Rep. Michael A. Feighan (OH-20), along with some other Democrats, insisted that "family unification" should take priority over "employability", on the premise that such a weighting would maintain the existing ethnic profile of the country. That change in policy instead resulted in chain migration dominating the subsequent patterns of immigration to the United States.[22][23] In removing racial and national discrimination the Act would significantly alter the demographic mix in the U.S.[24]

On October 3, 1965, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the legislation into law, saying, "This [old] system violates the basic principle of American democracy, the principle that values and rewards each man on the basis of his merit as a man. It has been un-American in the highest sense, because it has been untrue to the faith that brought thousands to these shores even before we were a country."[25]

Long-term effect

The proponents of the Hart–Celler Act argued that it would not significantly influence United States culture. President Johnson called the bill "not a revolutionary bill. It does not affect the lives of millions."[26] Secretary of State Dean Rusk and other politicians, including Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA), asserted that the bill would not affect the U.S. demographic mix.[27] However, the ethnic composition of immigrants changed following the passage of the law.[28][29] Specifically, the Hart–Celler Act allowed increased numbers of people to migrate to the United States from Asia and Africa. The 1965 act, however, imposed the first cap on immigration from the Americas. This marked the first time numerical limitations were placed on legal immigration from Latin American countries including Mexico.[30]

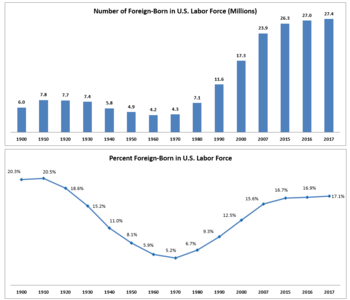

Prior to 1965, the demographics of immigration stood as mostly Europeans; 68 percent of legal immigrants in the 1950s came from Europe and Canada. However, in the years 1971–1991, immigrants from Hispanic and Latin American countries made up 47.9 percent of immigrants (with Mexico accounting for 23.7 percent) and immigrants from Asia 35.2 percent. Not only did it change the ethnic makeup of immigration, but it also greatly increased the number of immigrants—immigration constituted 11 percent of the total U.S. population growth between 1960 and 1970, growing to 33 percent from 1970 to 1980, and to 39 percent from 1980 to 1990.[31] The percentage of foreign-born in the United States increased from 5 percent in 1965 to 14 percent in 2016.[32]

The elimination of the National Origins Formula and the introduction of numeric limits on immigration from the Western Hemisphere, along with the strong demand for immigrant workers by U.S. employers, led to rising numbers of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. in the decades after 1965, especially in the Southwest.[33] Policies in the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 that were designed to curtail migration across the Mexico–U.S. border led many unauthorized workers to settle permanently in the U.S.[34] These demographic trends became a central part of anti-immigrant activism from the 1980s, leading to greater border militarization, rising apprehension of undocumented immigrants by the Border Patrol, and a focus in the media on the criminality of undocumented immigrants.[35]

The Immigration and Nationality Act's elimination of national and ethnic quotas has limited recent efforts at immigration restriction. In January 2017, President Donald Trump's Executive Order 13769 temporarily halted immigration from seven majority-Muslim nations.[36] However, lower federal courts ruled that the executive order violated the Immigration and Nationality Act's prohibitions of discrimination on the basis of nationality and religion. In June 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court overrode both appeals courts and allowed the second ban to go into effect, but carved out an exemption for persons with "bona fide relationships" in the U.S. In December 2017, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed the full travel ban to take effect, which excludes people who have a bona fide relationship with a person or entity in the United States.[37] In June 2018, the Supreme Court upheld the travel ban in Trump v. Hawaii, saying that the president's power to secure the country's borders, delegated by Congress over decades of immigration lawmaking, was not undermined by the president's history of arguably incendiary statements about the dangers he said some Muslims pose to the United States.[38]

See also

References

- "The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act)". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian. Retrieved May 15, 2019.

- Jennifer Ludden. "1965 immigration law changed face of America". NPR. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- Chin, Gabriel J. (January 11, 1996). "The Civil Rights Revolution Comes to Immigration Law: A New Look at the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965" (PDF). North Carolina Law Review. 75 (1).

- Gabriel J. Chin; Rose Cuison Villazor (2015). The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: Legislating a New America. Cambridge University Press. p. 27;. ISBN 978-1-107-08411-7.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Myer Feldman, Deputy Counsel to President John F. Kennedy and Counsel to President Lyndon B. Johnson; stated that both Kennedy and Johnson believed that "[w]hether the immigrant was from Asia, Africa, Italy or eastern Europe, or whether the immigrant was from England, France or Belgium, was not an acceptable basis for discrimination between them." Speaking of Asian immigration, Feldman writes: "[W]e did expect there would be an increase and we welcomed it."[3][4]

- "The unintended consequences of a 50-year-old U.S. immigration bill". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- The Washington Post states, "Almost no one realized the legislation would result in a demographic transformation of the United States, with a new population of unprecedented diversity."[6]

- "The Immigration Act of 1965 and the Creation of a Modern, Diverse America". Huffington Post. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "U.S. Immigration Before 1965". Retrieved September 3, 2016.

- Whitman, James Q. (2017). Hitler's American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law. Princeton University Press. pp. 37–43.

- "American laws against 'coloreds' influenced Nazi racial planners". The Times of Israel. Retrieved August 26, 2017

- "The Geopolitical Origins of the U.S. Immigration Acts of 1965". migrationpolicy.org. February 4, 2015. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- "Whom we shall welcome; report". archive.org. Retrieved March 1, 2016.

- Tracy J. Davis. "Opening the Doors of Immigration: Sexual Orientation and Asylum in the United States". Human Rights Brief. 6 (3). Archived from the original on August 22, 2002.

- Keely, Charles B. (Winter 1979). "The Development of U.S. Immigration Policy Since 1965". Journal of International Affairs. 33 (2).

- "Wages under Foreign Labor Certification". U.S. Department of Labor. Archived from the original on September 25, 2005. Retrieved December 3, 2015.

- Association of Centers for the Study of Congress. "Immigration and Nationalization Act". The Great Society Congress. Association of Centers for the Study of Congress. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- Keith Poole. "Senate Vote #232 (Sep 22, 1965)". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- Keith Poole. "House Vote #177 (Sep 30, 1965)". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- Bill Ong Hing (2012), Defining America: Through Immigration Policy, Temple University Press, p. 95, ISBN 978-1-59213-848-7

- "The Legacy of the 1965 Immigration Act". CIS.org.

- Tom Gjelten, Laura Knoy (January 21, 2016). NPR's Tom Gjelten on America's Immigration Story (Radio broadcast). The Exchange. New Hampshire Public Radio. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- Gjelten, Tom (August 12, 2015). "Michael Feighan and LBJ". Archived from the original on May 6, 2016. Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- Jennifer Ludden. "1965 immigration law changed face of America". NPR.

- "Remarks at the Signing of the Immigration Bill, Liberty Island, New York". October 3, 1965. Archived from the original on May 16, 2016. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- Johnson, L.B., (1965). President Lyndon B. Johnson's Remarks at the Signing of the Immigration Bill. Liberty Island, New York October 3, 1965 transcript at lbjlibrary.

- Jennifer Ludden. "1965 immigration law changed face of America". NPR.

- Ngai, Mae M. (2004). Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 266–268. ISBN 978-0-691-16082-5.

- Law, Anna O. (Summer 2002). "The Diversity Visa Lottery – A Cycle of Unintended Consequences in United States Immigration Policy". Journal of American Ethnic History. 21 (4).

- Wolgin, Philip (October 16, 2015). "The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 Turns 50". Retrieved March 27, 2019.

- Lind, Michael (1995). The Next American Nation: The New Nationalism and the Fourth American Revolution. New York: The Free Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-684-82503-8.

- "Modern Immigration Wave Brings 59 Million to U.S., Driving Population Growth and Change Through 2065". Pew Research Center. September 28, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- Massey, Douglas S. (September 25, 2015). "How a 1965 immigration reform created illegal immigration". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 20, 2016.

- Massey, Douglas S.; Durand, Jorge; Pren, Karen A. (March 1, 2016). "Why Border Enforcement Backfired". American Journal of Sociology. 121 (5): 1557–1600. doi:10.1086/684200. ISSN 0002-9602. PMC 5049707. PMID 27721512.

- Chavez, Leo (2013). The Latino threat: constructing immigrants, citizens, and the nation. Stanford University Press.

- See Wikisource:Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States

- Lydia Wheeler (4 December 2017). "Supreme Court allows full Trump travel ban to take effect". The Hill.

- "Trump's Travel Ban is Upheld by Supreme Court". The New York Times. June 26, 2018.

External links

- An Act to amend the Immigration and Nationality Act, and for other purposes Text of Public Law 89-236 – October 3, 1965

- Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 in the South Asian American Digital Archive (SAADA)

- Immigration Policy in the United States (2006), Congressional Budget office.

- The Great Society Congress