Ottoman–Portuguese conflicts (1538–1559)

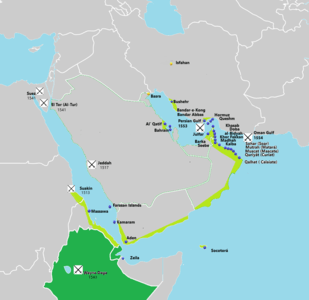

The Ottoman-Portuguese conflicts of 1538 to 1559 were a series of armed military encounters between the Portuguese Empire, the Kingdom of Hormuz, and the Ethiopian Empire against the Ottoman Empire and Adal Sultanate, in the Indian Ocean, the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea, and in East Africa. This is a period of battles in The Ottoman-Portuguese War.

| Ottoman–Portuguese conflicts (1538–1539) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Ottoman-Portuguese War and the Adal-Ethiopian War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Kingdom of Hormuz |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

Background

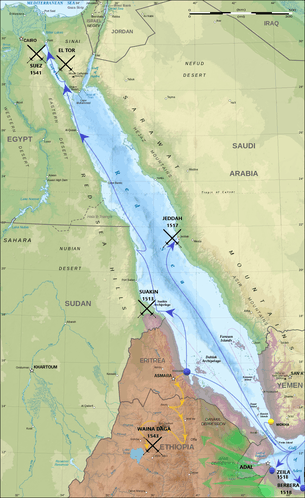

This war took place upon the backdrop of the Ethiopian-Adal War. Ethiopia had been invaded in 1529 by the Somali Imam Ahmed Gragn. Portuguese help, which was first asked by Emperor Lebna Dengel in 1520 to help defeat Adal while it was weak, finally arrived in Mitsiwa on February 10, 1541, during the reign of Emperor Galawdewos. The force was led by Cristóvão da Gama (second son of Vasco da Gama) and included 400 musketeers, several breech-loading field guns, and few Portuguese cavalry as well as a number of artisans and other non-combatants.

War begins

Major hostilities between Portugal and the Ottoman Empire began in 1538, when the Ottomans assisted the Sultanate of Gujarat with about 80 vessels to lay siege to Diu, which had been built by the Portuguese in 1535. The Ottoman fleet was led by Suleiman I's governor of Egypt Suleiman Pasha, but the attack was not successful and the siege was lifted.

The Portuguese under Estêvão da Gama (first son of Vasco da Gama) organized an expedition to destroy the Ottoman fleet at Suez, leaving Goa on December 31, 1540 and reaching Aden January 27, 1541. The fleet reached Massawa on February 12, where Gama left a number of ships and continued north. The Portuguese then sacked the Ottoman port of Suakin. Reaching Suez, he discovered that the Ottomans had long known of his raid, and foiled his attempt to burn the beached ships. Gama was forced to retrace his steps to Massawa, although pausing to attack the port of El-Tor (Sinai Peninsula).

Ethiopian Campaign

At Massawa, governor Estevão da Gama responded to an appeal by the Bahr Negus to assist the Christian Ethiopian Empire against invading Adalite forces. An expeditionary corps of 400 men was left behind, commanded by the governors' brother, Cristóvão da Gama. On February, 1542, the Portuguese were able to capture an important Adalite stronghold at the Battle of Baçente. The Portuguese were again victorious at the Battle of Jarte, killing almost all of the Turkish contingent. However, the Gragn then requested aid from the Ottoman governor of Yemen in Aden, who sent 2000 Arabian musketeers, 900 Turkish pikemen, 1000 Turkish foot musketeers, some Shqiptar foot soldiers (with muskets) and Turkish horsemen. In the Battle of Wofla, Somali and Turkish forces defeated the Portuguese, Gama was captured and killed by Gragn himself upon refusing to convert to Islam.

Gelawdewos was eventually able to reorganize his forces and absorb the remaining Portuguese soldiers and defeated Gragn (who was killed) at the Battle of Wayna Daga, marking the end of the Ethiopian-Adalite war (although warfare would resume not long after, at a much diminished scale).

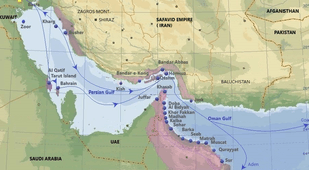

Persian Gulf campaigns

Elsewhere in the Indian Ocean naval combat was also intense. In 1547 the Admiral Piri Reis took command of the Ottoman-Egyptian fleet in the Indian Ocean and on 26 February 1548 recaptured Aden, in 1552 sacked Muscat. Turning further east, Piri Reis failed to capture Hormuz,[3] at the entrance of the Persian Gulf. Following these events, the Portuguese dispatched considerable reinforcements to Hormuz, and the following year defeated an Ottoman fleet at the Battle of the Strait of Hormuz.

In 1554 the Portuguese soundly defeated an Ottoman fleet led by Seydi Ali Reis in the Battle of the Gulf of Oman and in 1557 the Ottoman captured the port of Massawa to the province of Habesh. In 1559 the Ottomans laid siege to Bahrain, which had been conquered by the Portuguese in 1521 and ruled indirectly since then,[4] but the forces led by the Governor of Al-Hasa were decisively beaten back.[5] After this, the Portuguese effectively controlled the entirety of the naval traffic in the Persian Gulf. They raided the Ottoman coastal city of Al-Katif during this time, in 1559.[6]

Aftermath

Unable to decisively defeat the Portuguese or threaten their shipping, the Ottomans abstained from further substantial action in the near future, choosing instead to supply Portuguese enemies such as the Aceh Sultanate. The Portuguese on their part enforced their commercial and diplomatical ties with Safavid Persia, an enemy of the Ottoman Empire. A tense truce was gradually formed, wherein the Ottomans were allowed to control the overland routes into Europe, thereby keeping Basra, which the Portuguese had been eager to acquire, and the Portuguese were allowed to dominate sea trade to India and East Africa.[7] The Ottomans then shifted their focus to the Red Sea, which they had been expanding into previously, with the acquisition of Egypt in 1517, and Aden in 1538.[8]

See also

Notes

- Mesut Uyar, Edward J. Erickson, A military history of the Ottomans: from Osman to Atatürk, ABC CLIO, 2009, p. 76, "In the end both Ottomans and Portuguese had the recognize the other side's sphere of influence and tried to consolidate their bases and network of alliances."

- "Rise of Portuguese Power in India Por R. S. Whiteway". line feed character in

|title=at position 34 (help) - Holt, Lambton, Lewis, p. 332

- Larsen 1983, p. 68.

- Nelida Fuccaro (2009). Histories of City and State in the Persian Gulf: Manama Since 1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780521514354.

- İnalcık & Quataert 1994, p. 337.

- Dumper & Stanley 2007, p. 74.

- Shillington 2013, p. 954.

References

- Peter Malcolm Holt, Ann K. S. Lambton, Bernard Lewis The Cambridge history of Islam 1977.

- Attila and Balázs Weiszhár: Lexicon of War (Háborúk lexikona), Athenaum publisher, Budapest 2004.

- Britannica Hungarica, Hungarian encyclopedia, Hungarian World publisher, Budapest 1994.

- Shillington, Kevin (2013). Encyclopedia of African History. Routledge. ISBN 9781135456702.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dumper, Michael R.T.; Stanley, Bruce E. (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: a Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-Clio. ISBN 9781576079195.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- İnalcık, Halıl; Quataert, Donald (1994). An Economic and Social History of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914. Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 9780521343152.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Larsen, Curtis E. (1983). Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: the Geoarcheology of an Ancient Society. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-46906-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)