Ottoman naval expeditions in the Indian Ocean

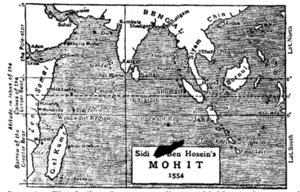

The Ottoman expeditions in the Indian Ocean (Turkish: Hint seferleri or Hint Deniz seferleri, lit. "Indian Ocean campaigns") were a series of Ottoman amphibious operations in the Indian Ocean in the 16th century. There were four expeditions between 1538 and 1554, during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent.

Background

After the voyages of Vasco da Gama, a powerful Portuguese Navy took control of the Indian Ocean in the early 16th century. It threatened the coastal cities of the Arabian Peninsula and India. The headquarters of the Portuguese Navy was in Goa, a city on the west coast of India, in 1510.

Ottoman control of the Red Sea meanwhile began in 1517 when Selim I annexed Egypt to the Ottoman Empire after the Battle of Ridaniya. Most of the habitable zone of the Arabian Peninsula (Hejaz and Tihamah) soon fell voluntarily to the Ottomans. Piri Reis, who was famous for his World Map, presented it to Selim just a few weeks after the sultan arrived in Egypt. Part of the 1513 map, which covers the Atlantic Ocean and the Americas, is now in the Topkapı Museum.[1] The portion concerning the Indian Ocean is missing; it is argued that Selim may have taken it, so that he could make more use of it in planning future military expeditions in that direction. In fact, after the Ottoman domination in the Red Sea, the Turco-Portuguese rivalry began. Selim entered into negotiations with Sultan Muzaffar II of Gujarat, (a sultanate in North West India), about a possible joint strike against the Portuguese in Goa.[2] However Selim died in 1520.

In 1525, during the reign of Suleiman I (Selim's son), Selman Reis, a former corsair, was appointed as the admiral of a small Ottoman fleet in the Red Sea which was tasked with defending Ottoman coastal towns against Portuguese attacks.[3] In 1534, Suleiman annexed most of Iraq and by 1538 the Ottomans had reached Basra on the Persian Gulf. The Ottoman Empire still faced the problem of Portuguese controlled coasts. Most coastal towns on the Arabian Peninsula were either Portuguese ports or Portuguese vassals. Another reason for Turco-Portugal rivalry was economic. In the 15th century, the main trade routes from the Far East to Europe, the so-called spice route, was via the Red Sea and Egypt. But after Africa was circumnavigated the trade income was decreasing.[4] While the Ottoman Empire was a major sea power in the Mediterranean, it was not possible to transfer the navy to the Red Sea. So a new fleet was built in Suez and named the "Indian fleet".[5] The apparent reason of the expeditions in the Indian Ocean, nonetheless, was an invitation from India.

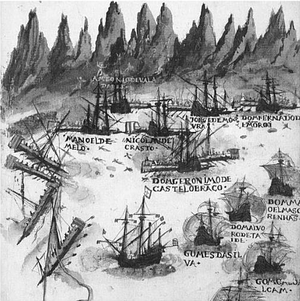

Expedition by Hadim Suleiman Pasha, 1538

Bahadur Shah, the son of Muzaffer II who had negotiated with Selim, the ruler of Gujerat, appealed to Constantinople for joint action against the Portuguese navy. Suleiman I used this opportunity to check Portuguese domination in the Indian Ocean and appointed Hadim Suleiman Pasha as the admiral of his Indian Ocean fleet. Hadim Suleiman Pasha's naval force consisted of some 90 galleys.[6] In 1538, he sailed to India via the Red and Arabian Seas, only to learn that Bahadur Shah had been killed during a clash with the Portuguese navy and his successor had allied himself with Portugal. After an unsuccessful siege at Diu, he decided to return. On his way back to Suez, however, he conquered most of Yemen, including Aden. After the expedition, Hadim Suleiman was promoted to grand vizier.

Expedition by Piri Reis, 1548–1552

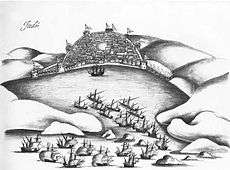

After the first expedition, the Portuguese navy had captured Aden and laid siege to Jeddah (in modern Saudi Arabia) and tried to penetrate the Red Sea. The aim of the second expedition was to restore Ottoman authority in the Red Sea and Yemen. The new admiral was Piri Reis, who had earlier presented his World Map to Selim. He recaptured Aden in 1548 from the Portuguese, thus securing the Red Sea.

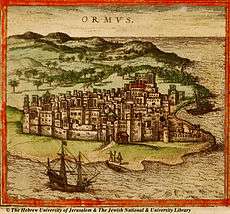

Three years later he sailed out from Suez again with 30 ships and the goal of wresting Hormuz Island, the key to the Persian Gulf, from Portugal. Piri Reis captured Muscat on his way, therefore extending Ottoman authority as far as Oman. He laid siege to Hormuz but was unsuccessful. He captured the town, but the citadel remained intact. After capturing Qatar peninsula failed the siege of Bahrain, and faced with reports of an approaching Portuguese fleet, Piri Reis decided to withdraw the fleet to Basra. He returned to Suez with two galleys which were his personal property.[7] The sultan sentenced Piri Reis to death for these acts, and had him executed in 1553.[8]

Expedition by Murat Reis the Elder, 1553

The purpose of this expedition was to bring the fleet back to Suez. The new admiral was Murat Reis the Elder, the former sanjak-bey (governor) of Qatif. While trying to sail out of the Persian Gulf, he encountered a large Portuguese fleet commanded by Dom Diogo de Noronha.[9] In the largest open-sea engagement between the two countries, Murat was defeated by the Portuguese fleet and had return to Basra.[10]

Expedition by Seydi Ali Reis, 1553

Seydi Ali Reis was appointed as the admiral after the failure of the third expedition, in 1553. But what he found in Basra was a group of neglected galleys. Nevertheless, after some maintenance, he decided to sail. He passed through the Strait of Hormuz and began sailing along Omani shores where he fought the Portuguese fleet twice. After the second battle Seydi Ali Reis flead the battle would eventually reach Gujarat, and was forced into the harbour of Surat by the caravels of Dom Jerónimo, where he was welcomed by the Gujarati governor. When the Portuguese Viceroy knew in Goa of their presence in India, he dispatched a two galleons and 30 oarships in October 10 to the city, to pressure the governor to hand over the Turks. The governor did not surrender them but proposed to destroy their ships, to which the Portuguese agreed. The remainder of the fleet was unserviceable, resulting in his return home overland with 50 men. Seydi Ali Reis then arrived at the royal court of the Mughal Emperor Humayun in Delhi where he met the future Mughal emperor Akbar who was then 12 years old.

The route from India to Turkey was a very dangerous one because of the war between the Ottoman Empire and Persia. Seydi Ali Reis returned home after the treaty of Amasya was signed between the two countries in 1555. He wrote a book named Mirror of Countries (Mir’at ül Memalik) about this adventurous journey and presented it to Suleiman I in 1557 .[11] This book is now considered one of the earliest travel books in Ottoman literature.

Aftermath

The naval expeditions in the Indian Ocean were only partially successful. The original goals of checking Portuguese domination in the ocean and assisting a Muslim Indian lord were not achieved. This was in spite of what an author has called "overwhelming advantages over Portugal", as the Ottoman Empire was wealthier and much more populous than Portugal, professed the same religion as most coastal populations of the Indian Ocean basin and its naval bases were closer to the theater of operations.[8]

On the other hand, Yemen, as well as the west bank of the Red Sea, roughly corresponding to a narrow coastal strip of Sudan and Eritrea, were annexed by Özdemir Pasha, the deputy of Hadım Suleiman Pasha. Three more provinces in East Africa were established: Massawa, Habesh (Abyssia) and Sawakin (Suakin). The ports around the Arabian Peninsula were also secured.[12]

Sometimes, Ottoman assistance to Aceh (in Sumatra, Indonesia), in 1569 is also considered to be a part of these expeditions (see Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis). However, that expedition was not a military expedition.[13]

It is known that Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, the grand vizier of the empire between 1565–1579, had proposed a canal between the Mediterranean and Red Seas. If that project could have been realized, it would be possible for the navy to pass through the canal and eventually into the Indian Ocean. However, this project was beyond the technological capabilities of the 16th century. The Suez Canal was not opened until some three centuries later, in 1869, by the largely-autonomous Khedivate of Egypt.

See also

- Ottoman Navy

- Ottoman-Portuguese conflicts

- Siege of Diu

- Siege of Diu (1531)

- Capture of Aden (1548)

- Capture of Muscat (1552)

- Ottoman campaign against Hormuz

References

- "Piri Reis' map". Archived from the original on 2013-08-13. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- History cooperative Archived 2011-05-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "Essays on Hurmuz" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-28. Retrieved 2011-04-16.

- Lord Kinross: Ottoman centuries (translated by Meral Gasıpıralı) Altın Kitaplar, İstanbul,2008, ISBN 978-975-21-0955-1, p.237

- Prof Dr. Yaşar Yücel-Prof Dr. Ali Sevim :Türkiye Tarihi II, Türk Tarih Kurumu Yayınları,1990,İstanbul

- Gabor Anaston-Bruce masters: The Encyclopaedia of the Ottoman Empire, ISBN 978-0-8160-6259-1 p.467

- World map of Piri Reis

- Soucek, Svat (June 2013), "Piri Reis. His uniqueness among cartographers and hydrographers of the Renaissance", in Vagnon, Emmanuelle; Hofmann, Catherine (eds.), Cartes marines : d'une technique à une culture. Actes du colloque du 3 décembre 2012., CFC, pp. 135–144, archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-06-27, retrieved 2016-08-21

- "Battle of the Strait of Hormuz (1553)".

- Giancarlo Casale: The Ottoman age of Exploration, Oxford University Press, 2010 ISBN 978-0-19-537782-8, p. 99.

- Summary of Mir'at ül Memalik

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Expo 70 ed, Vol.22, p.372

- "International Conference of Aceh and Indian Ocean" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2008-01-19.

Further reading

- Casale, Giancarlo (2010). The Ottoman Age of Exploration. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537782-8.