Organ concerto (Bach)

Johann Sebastian Bach's output include two types of organ concertos:

- arrangements of works by other composers

The five works catalogued as BWV 592–596 are arrangements which were realised by Johann Sebastian Bach as part of his Weimar concerto transcriptions. The organ concerto in E-flat major, BWV 597, is probably spurious.

- orchestral organ concertos (reconstructions)

These concertos have been reconstructed from cantata movements featuring organ obligato and from harpsichord concertos that have been linked to the organ on stylistic grounds. For example, the cantata Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal, BWV 146 contains a movement highlighting the organ and is also musically related to a surviving harpsichord concerto, thus giving scope for the recreation of a "lost" organ concerto.

| BWV | Key | Movements |

|---|---|---|

| 592 | G major | [Allegro] – Grave – [Presto] |

| 593 | A minor | [Allegro (or) Tempo Giusto] – Adagio – Allegro |

| 594 | C major | [Allegro] – Recitativ, Adagio – Allegro |

| 595 | C major | [no tempo indication] |

| 596 | D minor | [Allegro] - Grave - Fuga – Largo e spiccato – [Allegro] |

| 597 | E-flat major | [no tempo indication] – Gigue |

Weimar concerto transcriptions

In his Weimar period Bach transcribed concertos by, among others, Antonio Vivaldi and Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar for organ and for harpsichord. Most of the harpsichord transcriptions probably originated between July 1713 and July 1714. The organ concertos, BWV 592–596, are scored for two manual keyboards and pedal, and probably originated from 1714 to 1717.[1]

| BWV | Key | Model |

|---|---|---|

| 592 | G major | Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar: Violin Concerto in G major, a 8 |

| 593 | A minor | Vivaldi, Op. 3 No. 8: Concerto in A minor for two violins, RV 522 |

| 594 | C major | Vivaldi, RV 208: Violin Concerto Grosso Mogul in D major |

| 595 | C major | Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar: Violin Concerto in C major, first movement, and/or BWV 984/1 |

| 596 | D minor | Vivaldi, Op. 3 No. 11: Concerto in D minor for two violins, cello and strings, RV 565 |

Concerto in G major, BWV 592

This concerto is a transcription of Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar's Violin Concerto a 8 in G major. Bach arranged the same concerto for harpsichord (BWV 592a).[1][2][3]

Movements:[1]

- [without tempo indication – "Allegro assai" in the original]

- Grave (E minor)

- [without tempo indication – "Presto e staccato" in the original, "Presto" in Bach's harpsichord version]

Concerto in A minor, BWV 593

This concerto is a transcription of Antonio Vivaldi's double violin concerto in A minor, Op. 3 No. 8, RV 522.[1][4]

Movements:[1]

- [without tempo indication – "Allegro" in Vivaldi's original]

- Adagio (D minor; "Larghetto e spiritoso" in Vivaldi's original)

- Allegro (senza pedale a due claviere)

Concerto in C major, BWV 594

This concerto is a transcription of Antonio Vivaldi's Grosso mogul violin concerto in D major, RV 208, of which a variant, RV 208a, was published as Op. 7 No. 11.[1][5]

Movements:[1]

- [without tempo indication – "Allegro" in Vivaldi's original]

- Recitativ: Adagio (A minor; "Recitative: Grave" in Vivaldi's original)

- Allegro - Cadenza - Allegro

Concerto in C major, BWV 595

A transcription of the first movement of a lost concerto by Prince Johann Ernst of Saxe-Weimar, which has been reconstructed as a Concerto for Two Violins in C major.[1][6][7]

Only one movement, without tempo indication, but also indicated as Allegro.[1]

Exists in a variant for harpsichord, BWV 984 (first movement).[1]

Concerto in D minor, BWV 596

This concerto is a transcription of Antonio Vivaldi's double violin concerto in D minor, Op. 3 No. 11, RV 565.[1][8] There are registration markings in bars 1 and 21. The concerto became part of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach's repertoire, who appended a spurious note to the heading in which he claimed authorship (he was five in 1715).[9][10]

Movements:[1]

- [Allegro]

- Pleno: Grave

- Fuge

- Largo e spiccato

- [Allegro]

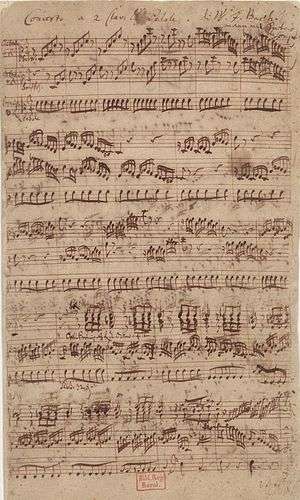

Manuscript

Bach's extant autograph has been dated from its watermark to 1714–1716. Exceptionally, it contains detailed specifications of organ registration and use of the two manuals. As explained in Williams (2003), their main purpose was to enable the concerto to be heard at Bach's desired pitch. The markings are also significant for what they show about performance practise at that time: during the course of a single piece, hands could switch manuals and organ stops could be changed.[11]

Bach's son Wilhelm Friedemann Bach added "di W. F. Bach manu mei Patris descript" to the heading on his father's autograph sixty or more years after it was written. The result was that up until 1911 the transcription was misattributed to Wilhelm Friedemann. Despite the fact that Carl Friedrich Zelter, director of the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin where many Bach manuscripts were held, had suggested Johann Sebastian as the author, the transcription was first published as a work by Wilhelm Friedemann in 1844 in the edition prepared for C.F. Peters by Friedrich Konrad Griepenkerl. The precise dating and true authorship was later established from the manuscript: the handwriting and the watermarks in the manuscript paper conform to cantatas known to have been composed by Bach in Weimar in 1714–1715.[1]

Movements

From the outset in the original piece, Vivaldi creates an unusual texture: the two violins play as a duet and then are answered by a similar duet for obbligato cello and continuo bass. On the organ Bach creates his own musical texture by exchanging the solo parts between hands and having the responding duet on a second manual. For Williams (2003), Bach's redistribution of the constantly repeated quavers in the original is "no substitute for the lost rhetoric of the strings."[12]

The dense chordal writing in the three introductory bars of the Grave is unusual and departs from Vivaldi's specification of "Adagio e spiccato". Bach adapted the ensuing fugue to the organ as follows: the pedal does not play the bass line of the original allegro but has an accompanying role, rather than being a separate voice in the fugue; the writing does not distinguish between soloists and ripieno; parts are frequently redistributed; and extra semiquaver figures are introduced, particularly over the prolonged pedal point concluding the piece. The resulting fugue is smoother than the original, which is distinguished by its clearly delineated sections. Williams (2003) remarks that the way Vivaldi inverts the fugue subject must have appealed to Bach.[13]

The scoring for organ in the ritornello and solo episodes of the Largo e spiccato movement—a form of Siciliano—is unusual in Bach's writing for organ. The widely spaced chords that accompany the solo melody in the original are replaced by simple chords in the left hand. For Griepenkerl, the sweetness of the melody reflected the tender personality of Wilhelm Friedemann.[14]

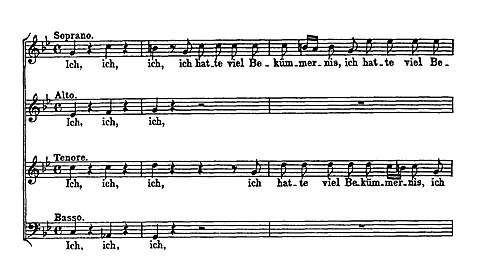

The last movement of Op.3, No.11 is composed in ritornello A–B–A form. In the opening bars the first and second violins play in tutti the opening theme with its repeated quavers and clashing dissonances. Bach used the same theme for the opening chorus of his cantata Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis, BWV 21, first performed on 17 June 1714, shortly before ill health forced Prince Johann Ernst to leave Weimar for treatment in Bad Schwalbach.[1]

Although each return of the theme with its chromatic falling bass accompaniment is instantly recognizable, Bach's allotting of parts between the two manuals (Oberwerk and Rückpositiv) can occasionally obscure Vivaldi's sharp distinction between solo and ripieno players. Various elements of Vivaldi's string writing, that would normally be outside Bach's musical vocabulary for organ compositions, are included directly or with slight adaptations in Bach's arrangement. As well as the dissonant suspensions in the opening quaver figures, these include quaver figures in parallel thirds, descending chromatic fourths, and rippling semidemiquavers and semiquavers in the left hand as an equivalent for the tremolo string accompaniment.

Towards the end of the piece, Bach fills out the accompaniment in the final virtuosic semiquaver solo episode by adding imitative quaver figures in the lower parts. Williams (2003) compares the dramatic ending—with its chromatic fourths descending in the pedal part—to that of the keyboard Sinfonia in D minor, BWV 779.[15]

Concerto in E-flat major, BWV 597

Probably neither composed nor transcribed by Bach, and rather a trio sonata, by a composer of a later generation, than a concerto.[16][17]

Movements:[18]

- [without tempo indication]

- Gigue

Orchestral concertos

In September 1725 Bach performed organ music, accompanied by other instruments, in Dresden. The works he performed there have not been identified. More than a year later he composed several cantatas with an organ obligato part. Several movements of such cantatas were derived from earlier lost concertos, and resurfaced in the harpsichord concertos BWV 1052, 1053 and 1059. Based on harpsichord concertos and earlier cantata movements orchestral organ concertos were reconstructed and/or transcribed and arranged.[19][20]

Various evidence has led Christoph Wolff and Gregory Butler to propose that Bach originally wrote the harpsichord concertos BWV 1052 and 1053 for organ and orchestra.[20][21] Among other evidence, they note that both concertos consist of movements that Bach had previously used as instrumental sinfonias in 1726 cantatas with obbligato organ providing the melody instrument (BWV 146, BWV 169 and BWV 188). A Hamburg newspaper reported on a recital by Bach in 1725 on the Silbermann organ in the Sophienkirche, Dresden, mentioning in particular that he had played concertos interspersed with sweet instrumental music ("diversen Concerten mit unterlauffender Doucen Instrumental-Music"). Wolff (2016), Rampe (2014), Gregory Butler and Matthew Dirst have suggested that this report might refer to versions of the cantata movements or similar works. Williams (2016) describes the newspaper article as "tantalising" but considers it possible that in the hour-long recital Bach played pieces from his standard organ repertoire (preludes, chorale preludes) and that the reporter was using musical terms in a "garbled" way.

In another direction Williams has listed reasons why, unlike Handel, Bach may not have composed concertos for organ and a larger orchestra: firstly, although occasionally used in his cantatas, the Italian concerto style of Vivaldi was quite distant from that of Lutheran church music; secondly, the tuning of the baroque pipe organ would jar with that of a full orchestra, particularly when playing chords; and lastly, the size of the organ loft limited that of the orchestra.[20][22][19][23] Wolff, however, notes that Bach's congregation did not object to his use of the organ obliggato in the sinfonia movements in the aforementioned cantatas.[20]

Discography

BWV 592–597

- Hans Fagius (2000). Bach Edition, Boxes 6 (CDs 41 and 45) and 22 (CDs 151–153 and 155). Recorded 1985–1986 and 1988–1989. Brilliant Classics 99365/3, /7; 99381/4, /5, /6, /8.

Orchestral organ concertos

- André Isoir and Le Parlement de Musique conducted by Martin Gester (1993). L'œuvre pour orgue et orchestre. Includes BWV 29/1 and reconstructions BWV 1052a, 1053a and 1059a. Calliope CAL 9720.

- Bart Jacobs and Les Muffatti (2019). Concertos for Organ and Strings. Includes Concerto in D major after BWV 169 and BWV 49, Concerto in D minor after BWV 146, BDW 188 and BWV 1052, Sinfonia in G major after BWV 156, Sinfonia in F major after BWV 75, Sinfonia in D major after BWV 29 and BWV 120a, Concerto in D moner after BWV 35 and BWV 1055, Concerto in G minor after BWV 1041 and BWV 1058. Ramée (Outhere Music) RAM 1804.

References

- Williams 2003, pp. 201–224.

- Work 00674 at Bach Digital website

- Work 00675 at Bach Digital website

- Work 00676 at Bach Digital website

- Work 00677 at Bach Digital website

- Work 00678 at Bach Digital website

- Freiburg Musica Poetica Ensemble; Hans Bergmann, conductor. Cantata, Concerto & Sonata. Hänssler Classic CD98.408, 2007

- Work 00679 at Bach Digital website

- Bach 2010, p. 25.

- Williams 2003, p. 220.

- Williams 2003, pp. 220–224.

- Williams 2003, pp. 221–222.

- Williams 2003, pp. 222–223.

- Williams 2003, p. 223.

- Williams 2003, p. 223–224.

- Williams 2003, p. 225.

- Work 00680 at Bach Digital website

- Williams 2003, pp. 225–226.

- Rampe 2014.

- Wolff 2016.

- Butler 2016.

- Wolff 2008.

- Williams 2016, pp. 370–371, 376.

Sources

- Bach, J.S. (2010), Dirksen, Pieter (ed.), Sonatas, Trios, Concertos, Complete Organ Works (Breitkopf Urtext), vol.5 EB 8805, Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, ISMN 979-0-004-18366-3 Introduction (in German and English) • Commentary (English translation—commentary in paperback original is in German)

- Butler, Gregory (2016), "The Choir Loft as Chamber: Concerted Movements by Bach from the Mid- to Late 1720s", in Matthew Dirst (ed.), Bach Perspectives, Volume 10, Bach and the Organ, University of Illinois Press, pp. 76–86, ISBN 9780252040191

- Rampe, Siegbert (2014), "Hat Bach Konzerte für Orgel und Orchester komponiert?" (PDF), Musik & Gottesdienst (in German), 68: 14–22, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-27, retrieved 2018-07-01

- Williams, Peter (2003), The Organ Music of J. S. Bach (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 201–224, ISBN 0-521-89115-9

- Williams, Peter (2016), Bach: A Musical Biography, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1107139251

- Wolff, Christoph (2008), "Sicilianos and Organ Recitals: Observations on J.S. Bach's concertos", in Gregory Butler (ed.), J. S. Bach's Concerted Ensemble Music: The Concerto, Bach Perspectives, 7, University of Illinois Press, pp. 97–114, ISBN 978-0252031656

- Wolff, Christoph (2016), "Did Bach write organ concertos? A propos the prehistory of cantata movements with obbligato organ", in Dirst, Matthew (ed.), Bach and the Organ, Bach Perspectives, 10, University of Illinois Press, pp. 60–75, ISBN 9780252040191, JSTOR 10.5406/j.ctt18j8xkb

External links

- At IMSLP website:

- BWV 592 and BWV 592a: Violin Concerto in G major (Johann Ernst Prinz von Sachsen-Weimar)

- Organ Concerto in A minor, BWV 593 (Bach, Johann Sebastian) and Concerto for 2 Violins in A minor, RV 522 (Vivaldi, Antonio)

- Organ Concerto in C major, BWV 594 (Bach, Johann Sebastian)

- Organ Concerto in C major, BWV 595 (Bach, Johann Sebastian) and Violin Concerto in C major (Johann Ernst Prinz von Sachsen-Weimar)

- Organ Concerto in D minor, BWV 596 (Bach, Johann Sebastian) and Concerto in D minor, RV 565 (Vivaldi, Antonio)

- Organ Concerto in E-flat major, BWV 597 (Bach, Johann Sebastian)

- Pages at James Kibbie's Bach Organ Works website containing free downloads of recordings on various 18th-century organs in AAC and MP3 format: BWV 592 • BWV 593 • BWV 594 • BWV 595 • BWV 596