Nucleobase

Nucleobases, also known as nitrogenous bases or often simply bases, are nitrogen-containing biological compounds that form nucleosides, which in turn are components of nucleotides, with all of these monomers constituting the basic building blocks of nucleic acids. The ability of nucleobases to form base pairs and to stack one upon another leads directly to long-chain helical structures such as ribonucleic acid (RNA) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA).

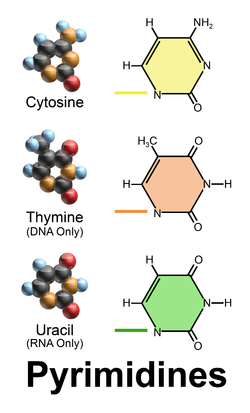

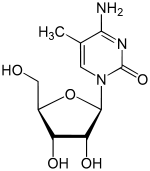

Five nucleobases—adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), thymine (T), and uracil (U)—are called primary or canonical. They function as the fundamental units of the genetic code, with the bases A, G, C, and T being found in DNA while A, G, C, and U are found in RNA. Thymine and uracil are identical except that T includes a methyl group that U lacks.

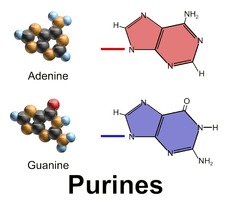

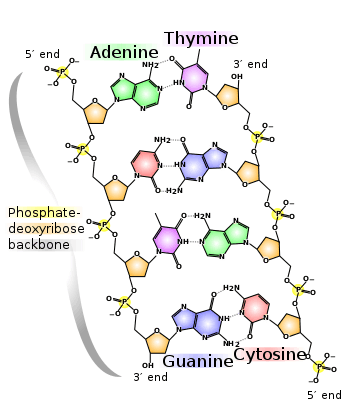

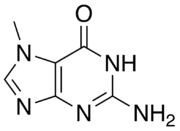

Adenine and guanine have a fused-ring skeletal structure derived of purine, hence they are called purine bases. The purine nitrogenous bases are characterized by their single amino group (NH2), at the C6 carbon in adenine and C2 in guanine.[1] Similarly, the simple-ring structure of cytosine, uracil, and thymine is derived of pyrimidine, so those three bases are called the pyrimidine bases. Each of the base pairs in a typical double-helix DNA comprises a purine and a pyrimidine: either an A paired with a T or a C paired with a G. These purine-pyrimidine pairs, which are called base complements, connect the two strands of the helix and are often compared to the rungs of a ladder. The pairing of purines and pyrimidines may result, in part, from dimensional constraints, as this combination enables a geometry of constant width for the DNA spiral helix. The A-T and C-G pairings function to form double or triple hydrogen bonds between the amine and carbonyl groups on the complementary bases.

Nucleobases such as adenine, guanine, xanthine, hypoxanthine, purine, 2,6-diaminopurine, and 6,8-diaminopurine may have formed in outer space as well as on earth.[2][3][4]

The origin of the term base reflects these compounds' chemical properties in acid-base reactions, but those properties are not especially important for understanding most of the biological functions of nucleobases.

Structure

At the sides of nucleic acid structure, phosphate molecules successively connect the two sugar-rings of two adjacent nucleotide monomers, thereby creating a long chain biomolecule. These chain-joins of phosphates with sugars (ribose or deoxyribose) create the "backbone" strands for a single- or double helix biomolecule. In the double helix of DNA, the two strands are oriented chemically in opposite directions, which permits base pairing by providing complementarity between the two bases, and which is essential for replication of or transcription of the encoded information found in DNA.

Modified nucleobases

DNA and RNA also contain other (non-primary) bases that have been modified after the nucleic acid chain has been formed. In DNA, the most common modified base is 5-methylcytosine (m5C). In RNA, there are many modified bases, including those contained in the nucleosides pseudouridine (Ψ), dihydrouridine (D), inosine (I), and 7-methylguanosine (m7G).[5][6]

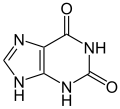

Hypoxanthine and xanthine are two of the many bases created through mutagen presence, both of them through deamination (replacement of the amine-group with a carbonyl-group). Hypoxanthine is produced from adenine, xanthine from guanine,[7] and uracil results from deamination of cytosine.

Modified purine nucleobases

These are examples of modified adenosine or guanosine.

| Nucleobase |  Hypoxanthine |  Xanthine |  7-Methylguanine |

| Nucleoside |  Inosine I |  Xanthosine X |  7-Methylguanosine m7G |

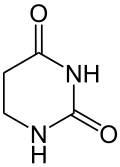

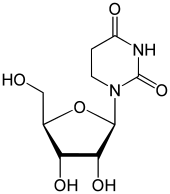

Modified pyrimidine nucleobases

These are examples of modified cytosine, thymine or uridine.

| Nucleobase |  5,6-Dihydrouracil |  5-Methylcytosine |  5-Hydroxymethylcytosine |

| Nucleoside |  Dihydrouridine D |  5-Methylcytidine m5C |

Artificial nucleobases

A vast number of nucleobase analogues exist. The most common applications are used as fluorescent probes, either directly or indirectly, such as aminoallyl nucleotide, which are used to label cRNA or cDNA in microarrays. Several groups are working on alternative "extra" base pairs to extend the genetic code, such as isoguanine and isocytosine or the fluorescent 2-amino-6-(2-thienyl)purine and pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde.

In medicine, several nucleoside analogues are used as anticancer and antiviral agents. The viral polymerase incorporates these compounds with non-canonical bases. These compounds are activated in the cells by being converted into nucleotides; they are administered as nucleosides as charged nucleotides cannot easily cross cell membranes. At least one set of new base pairs has been announced as of May 2014.[8]

References

- Berg JM, Tymoczko JL, Stryer L. "Section 25.2, Purine Bases Can Be Synthesized de Novo or Recycled by Salvage Pathways". Biochemistry. 5th Edition. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Callahan MP, Smith KE, Cleaves HJ, Ruzicka J, Stern JC, Glavin DP, House CH, Dworkin JP (August 2011). "Carbonaceous meteorites contain a wide range of extraterrestrial nucleobases". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. PNAS. 108 (34): 13995–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1106493108. PMC 3161613. PMID 21836052. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- Steigerwald, John (8 August 2011). "NASA Researchers: DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space". NASA. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ScienceDaily Staff (9 August 2011). "DNA Building Blocks Can Be Made in Space, NASA Evidence Suggests". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- BIOL2060: Translation

- "Role of 5' mRNA and 5' U snRNA cap structures in regulation of gene expression" – Research – Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- Nguyen T, Brunson D, Crespi CL, Penman BW, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR (April 1992). "DNA damage and mutation in human cells exposed to nitric oxide in vitro". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (7): 3030–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.7.3030. PMC 48797. PMID 1557408.

- Malyshev DA, Dhami K, Lavergne T, Chen T, Dai N, Foster JM, Corrêa IR, Romesberg FE (May 2014). "A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet". Nature. 509 (7500): 385–8. doi:10.1038/nature13314. PMC 4058825. PMID 24805238.