New Zealand Army

The New Zealand Army (Māori: Ngāti Tūmatauenga, "Tribe of the God of War") is the land component of the New Zealand Defence Force and comprises around 4,500 Regular Force personnel, 2,000 Territorial Force personnel and 500 civilians. Formerly the New Zealand Military Forces, the current name was adopted by the New Zealand Army Act 1950.[1] The New Zealand Army traces its history from settler militia raised in 1845.[2]

| New Zealand Army | |

|---|---|

| Māori: Ngāti Tūmatauenga | |

| |

| Founded | 1845 |

| Country | |

| Type | Army |

| Role | Land warfare |

| Size | Available: 6,492

|

| Part of | New Zealand Defence Force |

| Garrison/HQ | Wellington |

| Colors | Red and black |

| Anniversaries | ANZAC Day |

| Engagements | New Zealand Wars Boer War World War I World War II Malayan Emergency Korean War Indonesia-Malaysia confrontation Vietnam War Gulf War Somalia Yugoslav Wars East Timor Solomon Islands Iraq War War in Afghanistan |

| Website | army |

| Commanders | |

| Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief | Dame Patsy Reddy |

| Chief of Defence Force | Air Marshal Kevin Short |

| Chief of Army | Major General John Boswell |

| Insignia | |

| Logo | |

| Wartime flag |  |

New Zealand soldiers served with distinction in the major conflicts in the 20th century, including the Second Boer War, World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Malayan Emergency, Borneo Confrontation and the Vietnam War. Since the 1970s, deployments have tended to be assistance to multilateral peacekeeping efforts. Considering the small size of the force, operational commitments have remained high since the start of the East Timor deployment in 1999. New Zealand personnel also served in the First Gulf War, Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as several UN and other peacekeeping missions including the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands, the Sinai, South Sudan and Sudan.[3]

History

Musket Wars, settlement and the New Zealand Wars

War had been an integral part of the life and culture of the Māori people. The Musket Wars dominated the first years of European trade and settlement. The first European settlers in the Bay of Islands formed a volunteer militia from which some New Zealand Army units trace their origins. British forces and Māori fought in various New Zealand Wars starting in 1843, and culminating in the Invasion of the Waikato in the mid-1860s, during which colonial forces were used with great effect. From the 1870s, the numbers of Imperial (British) troops was reduced, leaving settler units to continue the campaign.

The first permanent military force was the Colonial Defence Force, which was active from 1862. This was replaced in 1867 by the Armed Constabulary, which performed both military and policing roles. After being renamed the New Zealand Constabulary Force, it was divided into separate military and police forces in 1886. The military force was called the Permanent Militia and later renamed the Permanent Force.

South Africa 1899–1902

Major Alfred William Robin led the First Contingent sent from New Zealand to South Africa to participate in the Boer War in October 1899.[4] The New Zealand Army sent ten contingents in total (including the 4th New Zealand Contingent), of which the first six were raised and instructed by Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Henry Banks, who led the 6th Contingent into battle. These were mounted riflemen, and the first contingents had to pay to go, providing their own horses, equipment and weapons.

The Defence Act 1909, which displaced the old volunteer system, remodelled the defences of the dominion on a territorial basis, embodying the principles of universal service between certain ages. It provided for a territorial force, or fighting strength, fully equipped for modern requirements, of thirty thousand men. These troops, with the territorial reserve, formed the first line; and the second line comprised rifle clubs and training sections. Under the terms of the Act, every male, unless physically unfit, was required to take his share of the defence of the dominion. The Act provided for the gradual military training of every male from the age of 14 to 25, after which he was required to serve in the reserve up to the age of thirty. From the age of 12 to 14, every boy at school performed a certain amount of military training, and, on leaving, was transferred to the senior cadets, with whom he remained, undergoing training, until 18 years of age, when he joined the territorials. After serving in the territorials until 25 (or less if earlier reliefs were recommended), and in the reserve until 30, a discharge was granted; but the man remained liable under the Militia Act to be called up, until he reached the age of 55. As a result of Lord Kitchener's visit to New Zealand in 1910, slight alterations were made—chiefly affecting the general and administrative staffs, and which included the establishment of the New Zealand Staff Corps—and the scheme was set in motion in January, 1911. Major-General Sir Alexander Godley, of the Imperial General Staff, was engaged as commandant.

World War I

In World War I New Zealand sent the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF), of soldiers who fought with Australians as the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps at Gallipoli, subsequently immortalised as "ANZACs". The New Zealand Division was then formed which fought on the Western Front and the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade fought in Palestine. After Major General Godley departed with the NZEF in October 1914, Major General Alfred William Robin commanded New Zealand Military Forces at home throughout the war, as commandant.

The total number of New Zealand troops and nurses to serve overseas in 1914–1918, excluding those in British and other dominion forces, was 100,000, from a population of just over a million. Forty-two percent of men of military age served in the NZEF. 16,697 New Zealanders were killed and 41,317 were wounded during the war—a 58 percent casualty rate. Approximately a further thousand men died within five years of the war's end, as a result of injuries sustained, and 507 died whilst training in New Zealand between 1914 and 1918. New Zealand had one of the highest casualty—and death—rates per capita of any country involved in the war.

World War II

In World War II the 2nd Division fought in Greece, Crete, the Western Desert Campaign and the Italian Campaign. Among its units was the famed 28th Māori Battalion. Following Japan's entry into the war, 3rd Division, 2 NZEF IP (in Pacific) saw action in the Pacific, seizing a number of islands from the Japanese. New Zealanders contributed to various Allied special forces units, such as the original Long Range Desert Group in North Africa and Z Force in the Pacific.

As part of the preparations for the possible outbreak of war in the Pacific, the defensive forces stationed in New Zealand were expanded in late 1941. On 1 November, three new brigade headquarters were raised (taking the total in the New Zealand Army to seven), and three divisional headquarters were established to coordinate the units located in the Northern, Central and Southern Military Districts.[5] The division in the Northern Military District was designated the Northern Division,[6] and comprised the 1st and 12th Brigade Groups.[7] Northern Division later became 1st Division. 4th Division was established in the Central Military District (with 2nd and 7th brigades), and 5th in the south (with 3rd, 10th and 11th brigades).

The forces stationed in New Zealand were considerably reduced as the threat of invasion passed. During early 1943, each of the three home defence divisions were cut from 22,358 to 11,530 men. The non-divisional units suffered even greater reductions.[8] The New Zealand government ordered a general stand-down of the defensive forces in the country on 28 June, which led to further reductions in the strength of units and a lower state of readiness.[9] By the end of the year, almost all of the Territorial Force personnel had been demobilised (though they retained their uniforms and equipment), and only 44 soldiers were posted to the three divisional and seven brigade headquarters.[10] The war situation continued to improve, and the 4th Division, along with the other two divisions and almost all the remaining Territorial Force units, was disbanded on 1 April 1944.[10][11]

The 6th New Zealand Division was also briefly formed as a deception formation by renaming the NZ camp at Maadi in southern Cairo, the New Zealanders' base area in Egypt, in 1942.[12] In addition, the 1st Army Tank Brigade (New Zealand) was also active for a time.

Post-War and NZ Army formation

The New Zealand Army was formally formed from the New Zealand Military Forces following the Second World War. Attention focused on preparing a third Expeditionary Force potentially for service against the Soviets. Compulsory military training was introduced to man the force, which was initially division-sized. The New Zealand Army Act 1950 stipulated that the Army would consist from then on of Army Troops (army headquarters, Army Schools, and base units); District Troops (Northern Military District, Central and Southern Military Districts, the 12 subordinate area HQs, elementary training elements, coastal artillery and composite AA regiments); and the New Zealand Division, the mobile striking force.[13] The division was alternatively known as '3NZEF'.

Korean War 1951–1957

The Army's first combat after the Second World War was in the Korean War, which began with North Korea's invasion of the South on 25 June 1950. After some debate, on 26 July 1950, the New Zealand government announced it would raise a volunteer military force to serve with the United Nations Command in Korea. The idea was opposed initially by Chief of the General Staff, Major-General Keith Lindsay Stewart, who did not believe the force would be large enough to be self-sufficient. His opposition was overruled and the government raised what was known as Kayforce, a total of 1,044 men selected from among volunteers. 16th Field Regiment, Royal New Zealand Artillery and support elements arrived later during the conflict from New Zealand. The force arrived at Pusan on New Year's Eve, and on 21 January, joined the British 27th Infantry Brigade representing the 1st Commonwealth Division, along with Australian, Canadian, and Indian forces. The New Zealanders immediately saw combat and spent the next two and a half years taking part in the operations which led the United Nations forces back to and over the 38th Parallel, later recapturing Seoul in the process.

The majority of Kayforce had returned to New Zealand by 1955, though it was not until 1957 that the last New Zealand soldiers had left Korea. In all, about 4700 men served with Kayforce.[14]

Malaya 1948–1964, Indonesia-Borneo 1963–1966

Through the 1950s, New Zealand Army forces were deployed to the Malayan Emergency, and the Confrontation with Indonesia. A Special Air Service squadron was raised for this commitment, but most forces came from the New Zealand infantry battalion in the Malaysia–Singapore area. The battalion was committed to the Far East Strategic Reserve.[15]

The 1957 national government defence review directed the discontinuation of coastal defence training, and the approximately 1000 personnel of the 9th, 10th, and 11th coastal regiments Royal New Zealand Artillery had their compulsory military training obligation removed. A small cadre of regulars remained, but as Henderson, Green, and Cook say, 'the coastal artillery had quietly died.'[16] All the fixed guns were dismantled and sold for scrap by the early 1960s. After 1945, the Valentine tanks in service were eventually replaced by about ten M41 Walker Bulldogs, supplemented by a small number of Centurion tanks. Eventually, both were superseded by FV101 Scorpion armoured reconnaissance vehicles.

Vietnam War 1964–1972

New Zealand sent troops to the Vietnam War in 1964 because of Cold War concerns and alliance considerations.

Initial contributions were a New Zealand team of non-combat army engineers in 1964 followed by a battery from the Royal New Zealand Artillery in 1965 which served initially with the Americans until the formation of the 1st Australian Task Force in 1966. Thereafter, the battery served with the task force until 1971.

Two Companies of New Zealand infantry, Whisky Company and Victor Company, served with the 1st Australian Task Force from 1967 until 1971. Some also served with the Australian and New Zealand Army Training teams until 1972.

NZ SAS arrived in 1968 and served with the Australian SAS until the Australian and New Zealand troop withdrawal in 1971.

Members from various branches of the NZ Army also served with U.S and Australian air and cavalry detachments as well as in intelligence, medical, and engineering.[17] In all, 3850 military personnel from all military branches of service served in Vietnam. New Zealand infantry accounted for approximately 1600 and the New Zealand artillery battery accounted for approximately 750.

Late 20th century: peacekeeping

The New Zealand Division was disbanded in 1961, as succeeding governments reduced the force, first to two brigades, and then a single one.[18] This one-brigade force became, in the 1980s, the Integrated Expansion Force, to be formed by producing three composite battalions from the six Territorial Force infantry regiments. In 1978, a national museum for the Army, the QEII Army Memorial Museum, was built at Waiouru, the Army's main training base in the central North Island.

After the 1983 Defence Review, the Army's command structure was adjusted to distinguish more clearly the separate roles of operations and base support training. There was an internal reorganisation within the Army General Staff, and New Zealand Land Forces Command in Takapuna was split into a Land Force Command and a Support Command.[19] Land Force Command, which from then on comprised 1st Task Force in the North Island and the 3rd Task Force in the South Island, assumed responsibility for operational forces, Territorial Force manpower management and collective training. Support Command which from then on comprised three elements, the Army Training Group in Waiouru, the Force Maintenance Group (FMG) based in Linton, and Base Area Wellington (BAW) based in Trentham, assumed responsibility for individual training, third line logistics and base support. Headquarters Land Force Command remained at Takapuna, and Headquarters Support Command was moved to Palmerston North.

The Army was prepared to field a Ready Reaction Force which was a battalion group based on 2/1 RNZIR; the Integrated Expansion Force (17 units) brigade sized, which would be able to follow up 90 days after mobilization; and a Force Maintenance Group of 19 units to provide logistical support to both forces.[20]

The battalion in South East Asia, designated 1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment by that time, was brought home in 1989.

In the late 1980s, Exercise Golden Fleece was held in the North Island. It was the largest exercise for a long period.[21]

During the later part of the 20th century, New Zealand personnel served in a large number of UN and other peacekeeping deployments including:

- United Nations Truce Supervision Organisation for over 50 years in the Middle East[22]

- Operation Agila in Rhodesia[23]

- Multinational Force and Observers (MFO) in the Sinai, Cambodia where members of the Royal New Zealand Corps of Signals (RNZSigs) were attached to the Australian Force Communications Unit (FCU) of the United Nations Transitional Authority Cambodia (UNTAC)[24]

- United Nations Operation in Somalia (UNOSOM) in Somalia[25]

- United Nations Accelerated Demining Programme (ADP) in Mozambique[26]

- United Nations Angola Verification Mission II in Angola[27]

- United Nations Protection Force in Bosnia[28]

- The Endeavour Peace Accord, Bougainville[29]

21st century

.jpg)

In the 21st century, New Zealanders have served in East Timor (1999 onwards),[30] Afghanistan,[31] and Iraq.[32]

NZDF forces have also been involved in international Peacekeeping actions such as Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (2003–2015), United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (2003–), United Nations Mine Action Coordination Centre in Southern Lebanon (2007–2008), and United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (2011.)

In 2003, the New Zealand government decided to replace its existing fleet of M113 armored personnel carriers, purchased in the 1960s, with the Canadian-built NZLAV,[33] and the M113s were decommissioned by the end of 2004. An agreement made to sell the M113s via an Australian weapons dealer in February 2006 had to be cancelled when the US State Department refused permission for New Zealand to sell the M113s under a contract made when the vehicles were initially purchased.[34] The replacement of the M113s with the General Motors LAV III (NZLAV) led to a review in 2001 on the purchase decision-making by New Zealand's auditor-general. The review found shortcomings in the defence acquisition process, but not in the eventual vehicle selection. In 2010, the government said it would look at the possibility of selling 35 LAVs, around a third of the fleet, as being surplus to requirements.[35]

On 4 September 2010, in the aftermath of the 2010 Canterbury earthquake, the New Zealand Defence Force deployed to the worst affected areas of Christchurch to aid in relief efforts and assist NZ police in enforcing a night time curfew at the request of Christchurch Mayor Bob Parker and Prime Minister John Key.[36][37]

Commemorations

NZ Army Day is celebrated on 25 March, the anniversary of the day in 1845 when the New Zealand Legislative Council passed the first Militia Act on 25 March 1845 constituting the New Zealand Army.[38]

ANZAC Day is the main annual commemorative activity for New Zealand soldiers. On 25 April each year the landings at Gallipoli are remembered, though the day has come to mean remembering the fallen from all wars in which New Zealand has been involved. While a New Zealand public holiday, it is a duty day for New Zealand military personnel, who, even if not involved in official commemorative activities are required to attend an ANZAC Day Dawn Parade in ceremonial uniform in their home location.

Remembrance Day, commemorating the end of World War I on 11 November 1918, is marked by official activities with a military contribution normally with parades and church services on the closest Sunday. However, ANZAC Day has a much greater profile and involves a much higher proportion of military personnel.

New Zealand Wars Day is commemorated on 28 October, this is the national day marking the 19th-century New Zealand Wars.[39]

The various regiments of the New Zealand Army mark their own Corps Days, many of which are derived from those of the corresponding British regiments. Examples are Cambrai Day on 20 November for the Royal New Zealand Armoured Corps, St Barbara's Day on 4 December for the Royal Regiment of New Zealand Artillery.

Current deployments

The New Zealand Army currently has personnel deployed in these locations:

- Iraq – Over 100 in a non-combat training mission to build the capacity of the Iraqi security forces working alongside the Australian Army based at Taji since 2015 as part of Operation Okra.[32]

- Afghanistan – Mentoring at the Afghan National Army Officer Training Academy.[31][40] The NZ Provincial Reconstruction Team (New Zealand) (NZ PRT), ended in April 2013.[31]

- Middle East – 2 serving in the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization.[40]

- South Sudan – At least 1 serving in the United Nations Mission in South Sudan.[40]

- South Korea – At least 1 serving in the United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission.[40]

Dress

Like all Commonwealth countries Uniforms of the New Zealand Army had historically followed those of the British Army. From World War II until the late 1950s British Battledress was worn with "jungle greens" being used as field wear thereafter, until the introduction of Military camouflage in 1980. Reforms in 1997 saw British-influenced modifications to the combat uniform and a further reform in 2008 saw the combat uniform updated to the modern ACU style.[41] A new camouflage pattern was adopted in 2013 and the uniform cut became a hybrid of the ACU and SOF styles.[42]

The high crowned Campaign hat, nicknamed the "lemon squeezer" in New Zealand, was for decades the most visible national distinction. This was adopted by the Wellington Regiment about 1911 and became general issue for all New Zealand units during the latter stages of World War I. The different branches of service were distinguished by coloured puggaree or wide bands around the base of the crown (blue and red for artillery, green for mounted rifles, khaki and red for infantry etc.). The "lemon squeezer" was worn to a certain extent during World War II, although often replaced by more convenient forage caps or berets, or helmets. After being in abeyance since the 1950s, the Campaign hat was reintroduced for ceremonial wear in 1977 for Officer cadets and the New Zealand Army Band.[43]

The M1 steel helmet was the standard combat helmet from 1960 to 2000 although the "boonie hat," was common in overseas theatres, such as in the Vietnam War. New Zealand forces also used the U.S PASGT helmet until 2009 after which the Australian Enhanced Combat Helmet became the standard issue helmet until 2019. The current combat helmet is the Viper P4 Advanced Combat Helmet by Revision Military.[44][45]

British DPM was adopted in 1980 as the camouflage pattern for clothing, the colours of which were further modified several times to better suit New Zealand conditions. This evolved pattern is now officially referred to as New Zealand disruptive pattern material (NZDPM.) A new field uniform, similar to the British Army's was issued in 1997.

.jpg)

In the 1990s a universal pattern mess uniform replaced various regimental and corps mess dress uniforms previously worn. The mess uniform is worn by officers and senior NCOs for formal evening occasions.

The wide-brimmed khaki slouch hat known as the Mounted Rifles Hat (MRH) with green puggaree replaced the khaki "No 2" British Army peaked cap as service dress headdress for all branches in 1998.

From 2002 under a "one beret" policy, berets of all branches of service are now universally rifle-green, with the exceptions only of the tan beret of the New Zealand Special Air Service and the blue beret of the New Zealand Defence Force Military Police.

In 2003 a desert DPM pattern, also based on the British pattern was in use with New Zealand peacekeeping forces in Iraq, Afghanistan and Africa. NZ SAS soldiers serving in Afghanistan were issued with Australian-sourced uniforms in Crye MultiCam camouflage.

In 2008 the field uniform was updated to an Army Combat Uniform-style cut and made in ripstop material.

In 2012 the MRH became the standard Army ceremonial headdress with the "lemon squeezer" being retained only for colour parties and other limited categories.[46]

NZDPM and NZDDPM were replaced in 2013 by a single camouflage pattern and a new uniform called the New Zealand Multi Terrain Camouflage Uniform (MCU.)[47] The shirt remains in an ACU-style however the pants are based on the Crye G3 combat pant with removable knee pads, usually otherwise associated with Special Forces and Police tactical unit assault uniforms.[48][49][50] The MCU, with the addition of a beret or sometimes the Mounted Rifles Hat, is now the working uniform for all branches and divisions of the NZDF.

Due to shortcomings and poor performances of the MCU uniform, the New Zealand Army announced plans to replace it in 2020 with a new camouflage pattern called NZMTP, based on the British Multi-Terrain Pattern (MTP) produced by Crye Precision in the United States. The new uniforms will revert back to the 2008 cut and be manufactured locally.[51]

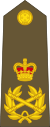

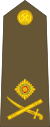

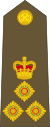

Rank structure and insignia

| Equivalent NATO Code | OF-10 | OF-9 | OF-8 | OF-7 | OF-6 | OF-5 | OF-4 | OF-3 | OF-2 | OF-1 | OF(D) & Student officer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

|

No equivalent |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Various | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Field marshal | Lieutenant-general | Major-general | Brigadier | Colonel | Lieutenant-colonel | Major | Captain | Lieutenant | Second lieutenant | Officer cadet | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Equivalent NATO code | OR-9 | OR-8 | OR-7 | OR-6 | OR-5 | OR-4 | OR-3 | OR-2 | OR-1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Edit) |

|

|

|

|

No equivalent | No equivalent | No insignia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Warrant officer class 1 | Warrant officer class 2 | Staff sergeant | Sergeant | Corporal | Lance corporal | Private (or equivalent) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

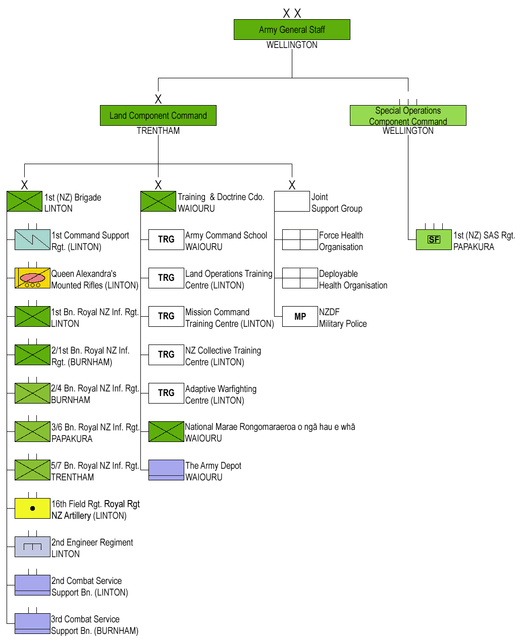

Structure

The New Zealand Army is commanded by the Chief of Army (Chief of the General Staff until 2002), who is a major general or two-star appointment. The current Chief of Army is Major General Dave Gawn. The Chief of Army has responsibility for raising, training and sustaining those forces necessary to meet agreed government outputs. For operations, the Army's combat units fall under the command of the land component commander, who is on the staff of the COMJFNZ at Headquarters Joint Forces New Zealand at Trentham in Upper Hutt. Forces under the land component commander include the 1st Brigade and 1 NZ SAS Group.

No. 3 Squadron RNZAF provides tactical air transport support.

Land Training and Doctrine Group

- Land Operations Training Centre Waiouru encompasses the main army trade schools:

- Combat School

- School of Artillery

- Logistics Operations School

- School of Tactics

- Royal New Zealand School of Signals

- School of Military Intelligence and Security

- Trade Training School (Trentham)

- School of Military Engineering, 2 Engineer Regiment (Linton)

Regiments and corps of the New Zealand Army

The following is a list of the Corps of the New Zealand Army, ordered according to the traditional seniority of all the Corps.[53]

- New Zealand Corps of Officer Cadets

- Royal Regiment of New Zealand Artillery

- Royal New Zealand Armoured Corps

- The Corps of Royal New Zealand Engineers

- Royal New Zealand Corps of Signals

- Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment

- The New Zealand Special Air Service

- New Zealand Intelligence Corps

- Royal New Zealand Army Logistic Regiment

- Royal New Zealand Army Medical Corps

- Royal New Zealand Dental Corps

- Royal New Zealand Chaplains Department

- New Zealand Army Legal Service

- Royal New Zealand Military Police

- Royal New Zealand Army Education Corps

- New Zealand Army Physical Training Corps

- Royal New Zealand Nursing Corps

Army Reserve

The Territorial Force (TF), the long established reserve component of the New Zealand Army, has as of 2009–2010 been renamed the Army Reserve, in line with other Commonwealth countries, though the term "Territorial Force" remains the official nomenclature in the Defence Act 1990.[54] It provides individual augmentees and formed bodies for operational deployments. There are Reserve units throughout New Zealand, and they have a long history. The modern Army Reserve is divided into three regionally-based battalion groups. Each of these is made up of smaller units of different specialities. The terms 'regiment' and 'battalion group' seem to be interchangeably used, which can cause confusion. However, it can be argued that both are accurate in slightly different senses. In a tactical sense, given that the Reserve units are groupings of all arms, the term 'battalion group' is accurate, though usually used for a much more single-arm heavy grouping, three infantry companies plus one armoured squadron, for example. NZ reserve battalion groups are composed of a large number of small units of different types.

The term 'regiment' can be accurately applied in the British regimental systems sense, as all the subunits collectively have been given the heritage of the former NZ infantry regiments (1900–1964). TF regiments prepare and provide trained individuals in order to top-up and sustain operational and non-operational units to meet directed outputs. TF regiments perform the function of a training unit, preparing individuals to meet prescribed outputs. The six regiments command all Territorial Force personnel within their region except those posted to formation or command headquarters, Military Police (MP) Company, Force Intelligence Group (FIG) or 1 New Zealand Special Air Services (NZSAS) Regiment. At a minimum, each regiment consists of a headquarters, a recruit induction training (RIT) company, at least one rifle company, and a number of combat support or combat service support companies or platoons.

3/1st Battalion, Royal New Zealand Infantry Regiment, previously existed on paper as a cadre.[55] If needed, it would have been raised to full strength through the regimentation of the Territorial Force infantry units. Army plans now envisage a three manoeuvre unit structure of 1 RNZIR, QAMR, and 2/1 RNZIR (light), being brought up to strength by TF individual and subunit reinforcements.

The New Zealand Cadet Corps also exists as an army-affiliated youth training and development organisation, part of the New Zealand Cadet Forces.

A rationalisation plan to amalgamate the then existing six Reserve Regiments to three, and to abolish one third of Reserve personnel posts, had been mooted for some years. This was finally agreed by the New Zealand government in August 2011, and was implemented in 2012.[56][57]

The Territorial Forces Employer Support Council is an organisation that provides support to Reserve personnel of all three services and their civilian employers. It is a national organisation appointed by the minister of defence to work with employers and assist in making Reserve personnel available for operational deployments.[58]

Equipment

- 105 NZ Light Armoured Vehicle (NZLAV)

- Light operational vehicles

- 321[59][60] Pinzgauer High Mobility All-Terrain Vehicle (261 non-armoured, 60 armoured)

- 122 (23 armoured) command and control variants

- 68 (37 armoured) crew served weapon carrier variants

- 95 general service variants

- 15 shelter carrier variants

- 8 ambulance variants

- 13 special operations

- Support vehicles

- Unimog trucks. Introduced over 8 years from 1981, the New Zealand Army procured 210 x 1.5T U1300L Unimogs and 412 x 4T U1700L Unimogs,[61] which after 30 years of service, are to be replaced by MAN trucks.[62][63]

- MB2228/41 trucks. Introduced over 8 years from 1981, the New Zealand Army procured 228 x 8T Mercedes Benz MB2228/41, are to be replaced by MAN trucks.[61]

- Mercedes-Benz Actros In 2010 New Zealand purchased 4 Actros to haul adjustable-width quad-axle low-loader semitrailers primarily for the transportation of LAVs (Light Armoured Vehicles).[64]

- JCB HMEE The NZ Army has six High Mobility Engineer Excavators (HMEEs) (also known as the Combat Engineer Tractor), which were delivered in January 2011.[65]

- MAN HX trucks were acquired as part of a project to purchase 194 Medium and Heavy Operational Vehicles to replace the in-service medium and heavy trucks.[66][62] The MHOV fleet has a mix of: 4 x 4, 6 tonne (115 HX60); 6 x 6, 9 tonne (58 HX58); and 8 x 8, 15 tonne (16 HX77) variants along with 8 x 8 (5 HX77) heavy equipment transporters planned to be capable of moving 30 tonne. The fleet is fitted with a mix of integrated Hiab cranes and self recovery winches, increasing flexibility on the battlefield and allowing self load/unload. The replacement program is to be completed in 2017.[63]

- M1089 Wrecker. Introduced in 1999 the NZ Army operates 5 US made FMTV A1 R M1089 A1 5-ton Wreckers.[67]

- Matbro Forklift. Introduced in 1999 the NZ Army operates 16 Matbro TS280, 2 5 tonne lift capacity Rough Terrain Forklift. These are wheeled 4 × 4 vehicles, capable of 2 wheel 4 wheel and crab steering. The Matbro has a quick change device that allows the vehicle to be converted from standard forks to extended forks or a multipurpose bucket that give the vehicle great versatility.[67]

- Skytrak Forklift. Introduced in 1995, the NZ Army operates 11 SkyTrak Rough Terrain Forklifts.[67]

- Karcher Field Kitchen. The NZ Army operates the Karcher Tactical Field Kitchen TFK which is a trailer mounted mobile kitchen unit comprising two pressure cookers two pressure roasters two ovens and two water boilers with heat supplied from four burners using a diesel and kerosene fuel mix The TFK has the capacity to produce up to 250 set meals or 500 hotbox meals within a two-hour period.[68]

- Fire support/artillery

- 50 x L16A2 81 mm Mortar

- 24 x 105 mm L119 Light Gun

- M6C-640T 60mm mortar

- Missile/rocket systems

- M72 Light Anti-Armour Weapon

- 42 x 84 mm Carl Gustav recoilless rifle M3 Man-portable Light Anti-armour Weapon

- 24 x Javelin Anti-Tank Guided Missile (ATGM) launchers, 120 missiles

- 12 x Mistral Very Low Level Air Defence Weapon (In storage)

- Small arms, light weapons

- Rifle 5.56mm LMT MARS-L[69] 8,800 CQB16 5.56 rifles with 406mm Barrels and spares.[70]

- Glock 17 Gen4 Programme.[71]

- M203 grenade launcher.

- Minimi 7.62 TR.

- FN MAG 58 7.62 mm.

- Benelli M3 12 gauge Shotgun.

- M2HB machine gun – .50 Calibre / 12.7mm Heavy Machine Gun.

- 7.62mm AW Sniper Rifle – replaced by the Barrett MRAD in 2018.[72]

- 12.7mm Arctic Warfare – replaced by the M107A1 in 2018.[72]

- L129A1 7.62mm Designated Marksman Weapon (DMW) from Lewis Machine Tools. Uses the LMT 308 MWS system.[73]

- Heckler & Koch GMG 40mm automatic grenade launcher.

- Small arms, light weapons – Retired / In storage

- Rifle 5.56mm Steyr (currently phased out in favour of the MARS-L)

- SIG P226 (currently phased out in favour of the Glock 17, gen-4)

- L1A1 Self-loading rifle (in storage)

- C9 Minimi 5.56mm Light Machine Gun (in storage)

See also

References

Citations

- "New Zealand Army Act 1950 (1950 No 39)". www.nzlii.org. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- G J Clayton (ed), A Short History of the New Zealand Army from 1840 to the 1990s, 1991

- IISS MIlitary Balance 2011, 263: ISAF, Multinational Force and Observers , 1 obs in UNAMI, 7 UNTSO, Sudan, RAMSI, and ISF in Timor.

- Stowers, Richard, Kiwi versus Boer: The First New Zealand Mounted Rifles in the Anglo-Boer War 1899–1902, 1992, Hamilton: Richard Stowers.

- Cooke (2011), p. 262

- "Barrowclough, Harold Eric". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Cooke (2011), pp. 262, 274

- Cooke and Crawford (2011), p. 279

- Cooke and Crawford (2011), p. 280

- Cooke and Crawford (2011), p. 281

- Cooke, Peter; Crawford, John (2011). The Territorials: The History of the Territorial and Volunteer Forces of New Zealand. Auckland: Random House. pp. 272–281. ISBN 9781869794460.

- Major General W.G. Stevens, 'Problems of 2 NZEF,' Chapter 4, Official History of the Second World War, 1958, NZ Electronic Text Centre accessed April 2009

- Damien Marc Fenton, 'A False Sense of Security,' Centre for Strategic Studies:New Zealand, 1998, p.12

- 'Impact of the War', URL: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/korean-war/impact, (Ministry for Culture and Heritage), updated 17-May-2017

- https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/the-malayan-emergency

- Henderson, Green, and Cook, 2008, 374.

- "The Flinkenberg List". Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- See for example Encyclopaedia of New Zealand 1966, accessed August 2009

- Report of the Naval Board of the Defence Council from 31 March 1983 – 1 April 1984 via Communicators' Association website.

- New Zealand Official Yearbook 1988–89 Archived 24 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine. See also Air New Zealand Almanac 1985 and New Zealand Army News, 1990s

- Jennings, P, Exercise Golden Fleece and the New Zealand military: lessons and limitations, Strategic and Defence Studies Centre. Research School of Pacific Studies. Australian National University, Working paper, 187, Canberra 1989. See also A Joint Force? The Move To Jointness And Its Implications for the New Zealand Defence Force

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/middle+east/default.htm

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/rhodesia/default.htm

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/cambodia/default.htm

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/somalia/default.htm

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/mozambique/default.htm

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/angola/default.htm

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/bosnia-herzegovina/default.htm

- http://army.mil.nz/about-us/what-we-do/deployments/previous-deployments/bougainville/default.htm

- Crawford & Harper 2001

- "Defence Force Mission in Afghanistan – A Significant Contribution". New Zealand Defence Force. 24 April 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- Keating, Chief of Defence Force Lt. Gen. Tim (24 February 2015). "NZDF's Training Mission to Iraq". New Zealand Defence Force. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- "NZ Army – Culture and History of Ngāti Tūmatauenga". New Zealand Army.

- "US blocks APC sale – Politics News". Television New Zealand. 20 February 2006. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015.

- "Govt to sell 35 army LAVs". 24 May 2010.

- "Weather the next threat after earthquake". Stuff.co.nz (Fairfax New Zealand). 4 September 2010. Archived from the original on 25 June 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- "Operation Christchurch Quake 2011". NZ Army. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011.

- Corbett, Corbett, D. A. (David Ashley) (1980). The regimental badges of New Zealand, an illustrated history of the badges and insignia worn by the New Zealand Army (Rev. and enl. ed.). Auckland: R. Richards. ISBN 0908596057. OCLC 14030948.

- "Date set to commemorate land wars". Manatū Taonga, the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 17 October 2017. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- "NZ Army Deployments" (PDF). New Zealand Army. February 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- http://www.nzdf.mil.nz/downloads/pdf/one-force/oneforceoct09.pdf

- http://army.mil.nz/downloads/pdf/army-news/armynews469.pdf

- Malcolm Thomas and Cliff Lord, page 129 Part One, New Zealand Army Distinguishing Patches 1911–1991, ISBN 0-473-03288-0

- http://www.army.mil.nz/about-us/who-we-are/uniforms/soldier-protected-systems.htm

- Baltlskin Viper P4 helmet https://www.revisionmilitary.com/en/head-systems/helmets/viper-p4-helmet

- Fairfax NZ News 3 May 2012

- "Multi-terrain Camouflage Uniform (MCU)". New Zealand Army.

- "MCU Trg Pants by bolty". Photobucket.

- http://i0.wp.com/www.whaleoil.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/20130618_OH_D1033071_0008.jpg

- http://www.army.mil.nz/nr/rdonlyres/48914ae1-e2b6-4257-91be-73babc86b8ce/0/oh_d1033071_0009.jpg

- Tso, Matthew (4 August 2019). "New Zealand Defence Force switches uniforms following review and complaints". Stuff.

- "NZ Army – Org Chart". New Zealand Army. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- "NZ Army – Our Ranks, Corps and Trades". www.army.mil.nz. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- Defence Act 1990 http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1990/0028/latest/DLM205891.html

- Ministry of Defence Briefing to the Incoming Government

- "Up to 600 Territorial soldiers' jobs to go" Otago Daily Times 12 Feb 2012 http://www.odt.co.nz/regions/otago/197535/600-territorial-soldiers-jobs-go

- "Battalion holds its Last Parade" Wanganui Chronicle 6 Aug 2012 http://www.wanganuichronicle.co.nz/news/battalion-holds-last-parade/1493375/

- Territorial Forces Employer Support Council web page http://www.reserves.mil.nz/tfesc/default.htm

- "LOV (Light Operational Vehicle)". NZ Army. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "Light Operational Vehicle". defense-aerospace.com. Briganti et Associes. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- "NZ Naval Report to the Defence Council – 1982". rnzncomms.org. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Truck Deal Driving Defence into The Future". NZDF.

- "Medium and Heavy Operational Vehicles". defence.govt.nz.

- "Cutting-edge Technology For New Army Actros Tractors". mercedes-benz.co.nz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "army capability" (PDF). NZ Army. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "New Zealand Army takes delivery of first 40 trucks from Rheinmetall MAN Military Vehicles Australia". 17 December 2013. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013.

- "Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Committee 2015/2016 Financial Review – Vote: Defence Force". www.parliament.nz. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "NZ Army – Karcher Field Kitchen". archive-nz.com. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- "Individual Weapon Replacement". defence.govt.nz. Archived from the original on 18 August 2015.

- "Individual Weapon Replacement". defence.govt.nz. 28 August 2015.

- "New Zealand Defence Force selects Glock 17 pistol | IHS Jane's 360". www.janes.com. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- "Defence Force buying two new weapons".

- "Individual Weapon Replacement". defence.govt.nz.

Sources

- Cooke, Peter; Crawford, John (2011). The Territorials: The History of the Territorial and Volunteer Forces of New Zealand. Auckland: Random House. ISBN 9781869794460.

- Crawford, John; Harper, Glyn (2001). Operation East Timor: The New Zealand Defence Force in East Timor 1999–2001. Auckland: Reed Publishing. ISBN 0790008238.

- Major G.J. Clayton, The New Zealand Army, A History from the 1840s to the 1990s, New Zealand Army, Wellington, 1990

- Damien Marc Fenton, A False Sense of Security?, Centre for Strategic Studies New Zealand

Further reading

- Desmond Ball, ed. The ANZAC Connection. George Allen & Unwin, 1985 (esp annex 'The New Zealand order of battle')

- A.E. Currie, Notes on the Constitutional History of the NZ Army from the Beginning to the Army Board Act, 1937, Crown Solicitors, March 1948, referenced in Peter Cooke, 'Defending New Zealand,' Part II.