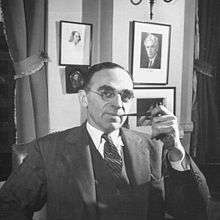

Morris Ernst

Morris Ernst (1888–1976) was an American lawyer and prominent attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). Morris Ernst was Jewish.[1]

Morris Ernst | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 23, 1888 |

| Died | May 21, 1976 (aged 87) |

| Alma mater | Williams College; New York Law School |

| Occupation | Attorney |

| Known for | Civil liberties litigaton |

Background

Morris Leopold Ernst was born in Uniontown, Alabama, on August 23, 1888, to Carl and Sarah Bernheim Ernst. His father, born in what is now Czechoslovakia, worked as a peddler and shopkeeper. His mother graduated from Hunter College.[2] The family moved to New York when Morris was two, and lived in several locations in Manhattan.[2] He attended the Horace Mann School and graduated from Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 1909. He studied law at night at New York Law School where he graduated in 1912 and was admitted to the New York bar in 1913.[2]

Career

Ernst practiced law in New York City and in 1915 co-founded the law firm of Greenbaum, Wolff & Ernst.[2] He joined the board of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in 1927 and was one of the most prominent and successful ACLU attorneys from the 1920s through the 1960s.

From 1929 to 1954, he shared the title of general counsel at the ACLU with Arthur Garfield Hays. He became vice chairman of the ACLU's board in 1955.[2]

In 1933, on behalf of Random House, he successfully defended James Joyce's novel Ulysses against obscenity charges, leading to its distribution in the U.S.[3] He won similar cases on behalf of Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness and Arthur Schnitzler's Casanova's Homecoming.[2][4]

In 1937, as attorney for the American Newspaper Guild, he argued successfully in the Supreme Court that it should uphold the constitutionality of the National Labor Relations Act (the Wagner Act) as applied to the press. The case established the right of media employees to organize labor unions.[2]

Ernst was a strong supporter of J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI. In 1940, as head of the ACLU, he agreed to bar communists from employment there and even discouraged their membership, basing his position on a distinction between the rights of the individual and the rights of groups. In 1946, President Harry Truman appointed him to the President's Committee on Civil Rights.[2]

He counted Justice Louis Brandeis as a close friend and later had close personal relationships with Presidents Franklin Roosevelt and Harry Truman and New York Governor Herbert Lehman.[2] Besides politicians, he also was friendly with many cultural figures, including Edna Ferber, E. B. White, Groucho Marx, Michael Foot, Compton Mackenzie, Al Capp, Charles Addams, Grandma Moses, Heywood Broun, and Margaret Bourke-White.

In 1956, Jesús Galíndez, a critic of the regime of Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, disappeared, abducted from New York City, it was charged, by Trujillo's agents. Hired by Trujillo to investigate the affair, Ernst's resulting report cleared the Trujillo regime of involvement in Galindez's disappearance, but the FBI and the press remained unconvinced.[5]

Personal life

In 1912, he married Susan Leerburger, with whom he had a son (who died in infancy) and a daughter. Susan died in 1922. Ernst married Margaret Samuels in 1923, and together they had a son and a daughter. Margaret died in 1964. Ernst kept a summer home on Nantucket, Massachusetts, and enjoyed sailing small boats. He died at home in New York City on May 21, 1976. He was survived by his son, both daughters, and five grandchildren.[2]

Morris Ernst's papers are housed at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.[6]

Published works

- Author

- If I Were a (Constitutional) Dictator (January 13, 1932) [7][8]

- Hold your tongue!: Adventures in Libel and Slander (1932)

- America's Primer (1931)

- The Ultimate Power (1937)

- Too Big (1940)

- Foreword to Ulysses (1942)

- The Best is Yet: Reflections of an Irrepressible Man (1945)

- The First Freedom (1946)

- So Far, So Good (1948)

- Report on the American Communist (1952)

- Touch Wood: A Year's Diary (1960)

- Untitled: The Diary of my 72nd Year (1962)

- The Pandect of C.L.D. (1965)

- The teacher, (editor, 1967)

- The Comparative International Almanac (1967)

- A Love Affair with the Law (1968)

- Utopia 1976 (1969)

- The Great Reversals: Tales of the Supreme Court (1973)

- Co-author

- with William Seagle, To the Pure: A Study of Obscenity And the Censor (1928)

- with Pare Lorentz, Censored: The Private Life of the Movies (1930)

- with Alexander Lindey Hold Your Tongue!: Adventures in Libel and Slander (1932)

- contributor to Sex in the Arts (1932)

- contributor to The Sex Life of the Unmarried Adult (1934)

- with Alexander Lindey The Censor Marches On: Recent Milestones in the Administration of the Obscenity Law in the United States (1940)

- with David Loth American Sexual Behavior and the Kinsey Report (1948)

- with David Loth The People Know Best: The Ballot vs. the Poll (1949)

- with David Loth, For Better Or Worse: New Approach to Marriage & Divorce (1952)

- with Alexander Lindy, Hold Your Tongue! The Layman's Guide to Libel and Slander (1950)

- with David Loth, Report on the American Communist (1952, 1962)

- with Alan Schwartz Privacy: The Right to be Let Alone (1962)

- with Alan Schwartz Censorship: The Search for the Obscene (1964)

- with David Loth How High Is Up?: Modern Law for Modern Man (1964)

- with Alan Schwarz Lawyers and What They Do (1965)

- with Eleanora B. Black Triple Cross Tricks (1968)

- with Malcolm A. Hoffmann Back and Forth: An Occasional, Casual Communication (1969)

- with David Loth The Taming of Technology (1972)

- contributor to Newsbreak (1974)

- Introduction to This Deception by Hede Massing (1951)

References

- Langer, “These 16 Jewish Heroes Rescued Books From The Jaws Of The Censors”. The Forward, Sep 22, 2019

- Whitman, Alden, “Morris Ernst, ‘Ulysses’”. The New York Times, May 23, 1976, p. 40.

- TIME: A Welcome to Ulysses", December 18, 1933

- Sherri Machlin, "Banned Books Week: The Well of Loneliness by Radclyffe Hall", New York Public Library, September 26, 2013.

- TIME: "Whitewash for Trujillo", June 9, 1958

- Harry Ransom Center: "Ransom Center Receives NEH Grant To Preserve Papers of Morris Ernst", accessed December 1, 2009

- unz.org

- Bloomfield, Maxwell (2000). Peaceful Revolution: Constitutional Change and American Culture from Progressivism to the New Deal. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 129.