Mont Blanc Tunnel

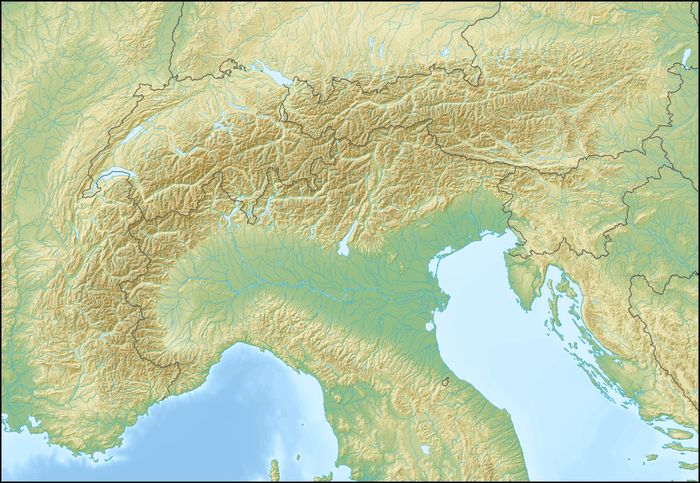

The Mont Blanc Tunnel is a highway tunnel in Europe, under the Mont Blanc mountain in the Alps. It links Chamonix, Haute-Savoie, France with Courmayeur, Aosta Valley, Italy, via European route E25, in particular the motorway from Geneva (A40 of France) to Turin (A5 of Italy). The passageway is one of the major trans-Alpine transport routes, particularly for Italy, which relies on this tunnel for transporting as much as one-third of its freight to northern Europe. It reduces the route from France to Turin by 50 kilometres (30 miles) and to Milan by 100 km (60 mi). Northeast of Mont Blanc's summit, the tunnel is about 15 km (10 mi) southwest of the tripoint with Switzerland, near Mont Dolent.

Mont Blanc Tunnel | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Location | Europe: western Alps |

| Coordinates | 45.854°N 6.914°E |

| Status | Open 24 hrs/day |

| Route | |

| Start | Chamonix, Haute-Savoie, France |

| End | Courmayeur, Aosta Valley, Italy |

| Operation | |

| Work begun | May 1959 (1946) |

| Constructed | 1959–1965 (1946) |

| Opened | 19 July 1965 |

| Operator | MBT-EEIG, controlled by both ATMB and SITMB |

| Traffic | Automotive |

| Character | Passenger and freight |

| Toll | €46 (one-way), 2019 passenger vehicle over €300 (one-way), three or more axles |

| Technical | |

| Length | 11.611 km (7.215 mi) |

| No. of lanes | 2 |

| Operating speed | 50–70 km/h (31–43 mph) |

| Highest elevation | 1,395 m (4,577 ft) center |

| Lowest elevation | 1,274 m (4,180 ft) France (NW) |

| Tunnel clearance | 4.35 m (14.3 ft) |

| Width | 8.6 m (28 ft) |

The agreement between France and Italy on building a tunnel was signed in 1949. Two operating companies were founded, each responsible for one half of the tunnel: the French Autoroutes et tunnel du Mont-Blanc (ATMB), founded on 30 April 1958, and the Italian Società italiana per azioni per il Traforo del Monte Bianco (SITMB), founded on 1 September 1957.[1] Drilling began in 1959 and was completed in 1962; the tunnel was opened to traffic on 19 July 1965.

The tunnel is 11.611 km (7.215 mi) in length, 8.6 m (28 ft) in width, and 4.35 m (14.3 ft) in height. The passageway is not horizontal, but in a slightly inverted "V", which assists ventilation. The tunnel consists of a single gallery with a two-lane dual direction road. At the time of its construction, it was three times longer than any existing highway tunnel.[2]

The tunnel passes almost exactly under the summit of the Aiguille du Midi. At this spot, it lies 2,480 metres (8,140 ft) beneath the surface, making it the world's second deepest operational tunnel [3] after the Gotthard Base Tunnel.

The Mont Blanc Tunnel was originally managed by the two building companies. Following a fire in 1999 in which 39 people died, which showed how lack of coordination could hamper the safety of the tunnel, all the operations are managed by a single entity: MBT-EEIG, controlled by both ATMB and SITMB together, through a 50–50 shares distribution.[4]

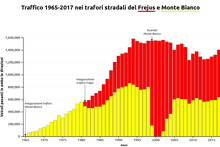

An alternative route for road traffic between France to Italy is the Fréjus Road Tunnel. Road traffic grew steadily until 1994, even with the opening of the Fréjus tunnel. Since then, the combined traffic volume of the former has remained roughly constant.

Construction statistics

- Workforce: five engineers and 350 workmen worked an estimated grand total of 4.6 million man-hours to complete the project

- Explosives: 711 tonnes (700 long tons; 784 short tons) of explosives were used to blast 555,000 m3 (19,600,000 cu ft) of rock

- Energy: 37 million kilowatt-hours and 2,700,000 litres (590,000 imp gal; 710,000 US gal) of fuel for trucks and engines

- Other facts: 771,240 bolts, 6,900 drill rods, and 300 tonnes (300 long tons; 330 short tons) of iron were used to support the vault, 5,000 m3 (180,000 cu ft) of formwork for 60,000 tonnes (59,000 long tons; 66,000 short tons) of cement (mixed with 280,000 m3 (9,900,000 cu ft) of aggregates)

History

The idea of building a tunnel underneath the Mont Blanc to avoid the need for lengthy circumnavigation dates back to the nineteenth century during the heyday of the railway. However, the idea did not receive widespread attention until 1907, when Francesco Farinet, a Member of Parliament of the Aosta Valley, advocated constructing of the tunnel.[5] In 1908, a first design was presented by French engineer Arnold Monod, to much interest from Italian and French politicians.[5] However, due to political turmoil and World War I and World War II, the project did not start until 1959, when excavations on the tunnel officially began.[5] This was preceded by the signing of a national charter for the tunnel construction, ratified by the parliaments of France (1957) and Italy (1954). That same year, the STMB (Société du tunnel du Mont Blanc) was formed, which became ATMB (Autoroutes et Tunnel du Mont Blanc) in 1996.[5]

In 1962, the French and Italian drilling teams met on 4 August. The opening was successful, with an axis variation of less than 13 centimetres (5 inches).[6] Three years later the tunnel was inaugurated by the French president, Charles de Gaulle, and the Italian President, Giuseppe Saragat on 16 July 1965. Tunnel opens to traffic on 19 July.[6] Surveillance cameras were installed in 1978.[7]

The tunnel underwent extensive modernisation works in 1990, including the addition of safety features such new video surveillance cameras, 8 pressurized emergency shelters, a sprinkler system and other safety maintenance. In 1997, a fire detection system was installed along with centralized safety equipment management, and new variable message signs.[8]

On the morning of 24 March 1999, the engine of a Belgian transport truck caught fire in the tunnel (see below).[1] The event expanded into a catastrophe which cost the lives of 39 people[9] and led to a three-year tunnel closure until 9 March 2002.[10] The reopening followed an extensive overhaul of the safety features.[11]

The highway trunk from Aosta to the tunnel on the Italian side was completed in 2007.[12]

Mont Blanc Tunnel 1999 fire

On the morning of 24 March 1999, 39 people died when a Belgian transport truck carrying flour and margarine entered the French-side portal and caught fire in the tunnel.[9][1] After several kilometres, the driver realized something was wrong as cars coming in the opposite direction flashed their headlights at him; a glance in his mirrors showed white smoke coming out from under his cabin. This was not yet a fire emergency; there had been 16 other truck fires in the tunnel over the previous 35 years, always extinguished on the spot by the drivers. At 10:53 CET, the driver of the vehicle, Gilbert Degrave, stopped in the middle of the tunnel to attempt to fight the fire but he was suddenly forced back by flames from his cabin.[1] With Degrave unable to fight the fire, he was forced to flee.

At 10:55, the tunnel employees triggered the fire alarm and stopped any further traffic from entering. At this point there were at least 10 cars and vans and 18 trucks in the tunnel that had entered from the French side. A few vehicles from the Italian side passed the Volvo truck without stopping. Some of the cars from the French side managed to turn around in the narrow two-lane tunnel to retreat back to France, but negotiating the road in the dense smoke that had rapidly filled the tunnel quickly made this impossible. The larger trucks did not have the space to turn around, and reversing out was not an option.

Most drivers rolled up their windows and waited for rescue. The ventilation system in the tunnel drove toxic smoke back down the tunnel faster than anyone could run to safety. These fumes quickly filled the tunnel and caused vehicle engines to stall because of lack of oxygen. This included fire engines which, once affected, had to be abandoned by the firefighters. Many drivers near the blaze who attempted to leave their cars and seek refuge points were quickly overcome.

Within minutes, two fire trucks from Chamonix responded to the unfolding disaster. The fire had melted the wiring and plunged the tunnel into darkness; in the smoke and with abandoned and wrecked vehicles blocking their path, the fire engines were unable to proceed. The fire crews instead abandoned their vehicles and took refuge in two of the emergency fire cubicles (fire-door sealed small rooms set into the walls every 600 metres). As they huddled behind the fire doors, they could hear burning fuel roll down the road surface, causing tires and fuel tanks to explode. They were rescued five hours later from a third fire crew that responded and reached them via a ventilation duct; of the 15 firefighters that had been trapped, 14 were in serious condition and one (their commanding officer) died in the hospital.

Some victims escaped to the fire cubicles. The original fire doors on the cubicles were rated to survive for two hours. Some had been upgraded in the 34 years since the tunnel was built to survive for four hours. The fire burned for 53 hours and reached temperatures of 1,000 °C (1,830 °F), mainly because of the margarine load in the trailer, equivalent to a 23,000-litre (5,100 imp gal; 6,100 US gal) oil tanker, which spread to other cargo vehicles nearby that also carried combustible loads. The fire trapped around 40 vehicles in dense and poisonous smoke (containing carbon monoxide and cyanide). Due to weather conditions at the time, airflow through the tunnel was from the Italian side to the French side.[13] Authorities compounded the effect by pumping in further fresh air from the Italian side, feeding the fire and forcing poisonous black smoke through the length of the tunnel. Only vehicles below the fire on the French side of the tunnel were trapped, while cars on the Italian side of the fire were mostly unaffected. There were 27 deaths in vehicles, and 10 more died trying to escape on foot. All the deceased were ultimately reduced to bones and ash. Of the initial 50 people trapped by the fire, 12 survived.[1] It was more than five days before the tunnel cooled sufficiently to start repairs.

Pierlucio Tinazzi

Pierlucio Tinazzi, an Italian security guard employed by the SITMB, was credited with saving at least 10 of the 12 survivors around the time of the accident.[1] Other reports and findings by French police[14] appear to debunk this, suggesting that Tinazzi was unable to save anyone, although he died trying to do so.[15] It is possible that his identity was confused with another security guard named Patrick Devouassoux, who was on the other side of the tunnel.[16] What is known about Tinazzi is that he was on the French side at the time emergency services had given up. He donned breathing equipment and drove into the tunnel on his BMW K75 motorcycle. He was in radio contact with the Italian side for over an hour before succumbing to the intense heat. His motorcycle melted into the road surface after he dragged an unconscious truck driver behind a fire door. A commemorative plaque at the Italian entrance honours him.[17]

Aftermath

The tunnel underwent major changes in the three years it remained closed after the fire.[18] Renovations include computerised detection equipment, extra security bays, a parallel escape shaft and a fire station in the middle of the tunnel complete with double cabbed fire trucks. The safety shafts also have clean air flowing through them via vents. Any people in the security bays now have video contact with the control centre, so they can communicate with the people trapped inside and inform them about what is happening in the tunnel more clearly.

A remote site for cargo safety inspection was created on each side: Aosta in Italy and Passy-Le Fayet in France. Here all trucks are inspected well before the tunnel entrance. These remote sites are also used as staging areas, to smooth the peaks of commercial traffic.

The experience gained from the investigation into the fire was one of the principal factors that led to the creation of the French Land Transport Accident Investigation Bureau.[19]

TV documentaries were also made concerning the disaster, all distributed worldwide and focussing on either safety aspects or the circumstances that turned what should have been a serious, but controllable incident into a disaster. The first, Seconds from Disaster – Tunnel Inferno (aired 2004), was a reconstruction of the events leading up to and during the disaster and the conclusions of the investigation that followed. The second, Into the Flames – Fire Underground (aired 2006), revisited the circumstances and showed how new technology in the form of a new type of fire extinguisher could have reduced the scale of the disaster and enabled the fire service to reach and remain in the vicinity to fight the fire.

Manslaughter trial

In Grenoble, France, 16 people and companies were tried on 31 January 2005 for manslaughter. Defendants in the trial included:

- Gilbert Degrave, the Belgian driver of the truck that caused the fire

- Volvo, the truck's manufacturer

- French and Italian managers of the tunnel

- ATMB and SITMB

- Safety regulators

- Mayor of Chamonix

- A senior official of the French Ministry of Public Works

The cause of the fire is disputed. One account reported it to be a cigarette stub carelessly thrown at the truck, which supposedly entered the engine induction snorkel above the cabin, setting the paper air filter on fire. Others blamed a mechanical or electrical fault, or poor maintenance of the truck's engine. The closest smoke detector was out of order, and French emergency services did not use the same radio frequency as those inside the tunnel. The Italian company responsible for operating the tunnel, SITMB, paid €13.5 million ($17.5 million US) to a fund for the families of the victims. Édouard Balladur, former president of the French company operating the tunnel (from 1968 to 1980), and later Prime Minister of France, underwent a witnesses examination. He was asked about the security measures that he ordered to or did not order to be carried out. Balladur claimed that the catastrophe could be attributed to the fact the tunnel had been divided into two sections operated by two companies (one in France, the other in Italy), which failed to coordinate the situation. On 27 July 2005, thirteen defendants were found guilty, and handed sentences ranging from fines to suspended prison sentences, to six months in jail:

- Gérard Roncoli, the head of security at the tunnel, was convicted and sentenced to six months in jail plus an additional two-year suspended sentence, the heaviest sentence levied against any of the defendants. The sentence was upheld on appeal.[20]

- Remy Chardon, former president of the French company operating the tunnel, was convicted and received two-year suspended jail term and a fine of approximately US$18,000.

- Gilbert Degrave, the driver of the truck, received a four-month suspended sentence.

- Seven other people, including the tunnel's Italian security chief, were handed suspended terms and fines.

- Three companies were fined up to US$180,000 each.

- The prosecutor dropped the charges against Volvo.

Traffic

In 2010, the average traffic volume was 4,945 vehicles per day, or around 1.80 million vehicles per year. In 2011, there were an average of 5,113 vehicles per day (about 1.87 million vehicles per year).

Although several lines of vehicles can queue up at the toll station, only a limited number of vehicles per unit time is allowed to transit the tunnel to ensure a safety distance between them.

Within the tunnel, a minimum speed of 50 km/h and a maximum speed of 70 km/h applies, while the prescribed distance between vehicles is 150 m; trucks are allowed to enter in groups of five. These security measures were taken as a consequence of the 1999 tunnel fire.

Pedestrians can cross the tunnel by bus; bicycles can also be carried through the tunnel with a reservation.

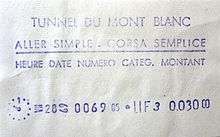

Toll

The tunnel crossing is subject to a toll; the toll differs from Italy to France because of their different VAT rates.

In 2013, the one-way ticket for a car was €40.90 (€41.40 on the Italian side), while the return ticket, valid for 7 days, was €51 (€51.60 on the Italian side).[21] In 2016, the one-way ticket for a car cost €43.50 (€44.20 on the Italian side).

Mont Blanc Tunnel Tolls on the Italian side from 1st January 2019 (22% VAT included)

| Vehicle Type | One Way | Return |

|---|---|---|

| Cars | €46.40 | €57.90 |

| Motorbikes | €30.70 | €38.50 |

| Caravans | €61.40 | €77.10 |

Mont Blanc Tunnel Tolls on the French side from 1st January 2019 (20% VAT included)

| Vehicle Type | One Way | Return |

|---|---|---|

| Cars | €45.60 | €56.90 |

| Motorbikes | €30.20 | €37.90 |

| Caravans | €60.40 | €75.90 |

See also

- National Geographic Seconds From Disaster episodes

References

- Barry, Keith (15 July 2010). "July 16, 1965: Mont Blanc Tunnel Opens". Wired. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- Soule, Gardner (December 1959). "World's longest auto tunnel to pierce the Alps". Popular Science. pp. 121–123/236–238.

- "Today in Science History". Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Mont Blanc Tunnel at age 46". www.tunneltalk.com. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- Barry, Keith (2010-07-16). "July 16, 1965: Mont Blanc Tunnel Opens". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "Our work on the Mont Blanc Tunnel - ATMB". www.atmb.com. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "History of the Tunnel". Autoroutes et Tunnel du Mont Blanc. Archived from the original on January 4, 2014. Retrieved December 20, 2013.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 29, 2012. Retrieved September 27, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Mont Blanc tunnel reopens". 2002-03-09. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "The security features of the Mont Blanc Tunnel | DW | 17.07.2015". DW.COM. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "A5 Mont Blanc-Aosta Motorway - Courmayeur- Morgex Section – Lot No 2 - Salini Impregilo". www.salini-impregilo.com. Retrieved 2018-12-21.

- "Case Studies: Historical Fires: Mont Blanc Tunnel Fire, Italy/France". University of Manchester. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018.

- "I wrote a story that became a legend. Then I discovered it wasn't true".

- Gardiner, Mark. "A Deadly Blaze in the Alps Made a Biker a Hero and Tunnels Safer for All". New York TImes. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "I wrote a story that became a legend. Then I discovered it wasn't true".

- "Pierlucio Tinazzi". Find a Grave. Retrieved 8 January 2010.

- Bailey, Colin. "Infrastructural Fires: Mont Blanc Tunnel, Italy". www.mace.manchester.ac.uk. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- "Land transport accident investigation bureau (BEA-TT)". French Land Transport Accident Investigation Bureau. Retrieved 24 July 2009.

- "Procès du Mont-Blanc : Gérard Roncoli condamné en appel à 6 mois de prison ferme". Le Monde.fr. Lemonde.fr. 14 June 2007. Retrieved 2016-04-23.

- "Wikiwix's cache". archive.wikiwix.com. Archived from [rl=http://www.tunnelmb.net/v3.0/frasp/tariffr.asp the original] Check

|url=value (help) on|archive-url=requires|archive-date=(help). Retrieved 2018-11-12. - "Mont Blanc Tunnel Toll Prices - Get from France to Italy".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mont Blanc Tunnel. |

- Official website

- "Traffic Tunnel to Pierce Mt Blanc." Popular Mechanics, April 1952, pp. 92–96. Detailed drawings of planned tunnel construction

- ATMB, Official Company Website (in English)

- ATMB, Official Company Website (in French)

- ATMB, Official Company Website (in Italian)

- Mont-Blanc Tunnel at Structurae

- Chamonix-Mont-Blanc Map

- BBC story on fire trial

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Great St Bernard Tunnel 5.80 km (3.60 mi) |

World's longest road tunnel 1965–1978 |

Succeeded by Arlberg Road Tunnel 13.98 km (8.69 mi) |