Mining in Wales

Mining in Wales provided a significant source of income to the economy of Wales throughout the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. It was key to the Industrial Revolution.

Wales was famous for its coal mining, in the Rhondda Valley, the South Wales Valleys and throughout the South Wales coalfield and by 1913 Barry had become the largest coal exporting port in the world, with Cardiff as second, as coal was transported down by rail. Northeast Wales also had its own coalfield and Tower Colliery (closed January 2008) near Hirwaun is regarded by many as the oldest open coal mine and one of the largest in the world. Wales has also had a significant history of mining for slate, gold and various metal ores.

History

There had been small-scale mining in Wales in the pre-Roman British Iron Age, but it would be undertaken on an industrial scale under the Romans, who completed their conquest of Wales in AD 78. Substantial quantities of gold, copper, and lead were extracted, along with lesser amounts of zinc and silver. Mining would continue until the process was no longer practical or profitable, at which time the mine would be abandoned.[1] The extensive excavations of the Roman operations at Dolaucothi provide a picture of the high level of Roman technology and the expertise of Roman engineering in the ancient era.

Coal mining

There is evidence of mining in the Blaenavon area going back to the 14th century, and there is evidence of mine workings at Mostyn as far back as 1261,[2] but it is believed to have been practised even as early as Roman times. The coal mining industry burgeoned throughout the Industrial Revolution and into the 19th century, when shafts were sunk to complement the open-cast mining and drift mining already exploiting the ample and obvious coal resources.

During the first half of the nineteenth century mining was often at the centre of working-class discontent in Wales, and a number of uprisings such as the Merthyr Rising in 1831 against employers were a characteristic of the Industrial Revolution in Wales, Dic Penderyn became a martyr to industrial workers. The Chartist movement and the 1839 Newport Rising showed the growing concerns and awareness of the work force of their value to the nation. Although the Factory Acts of the 1830s and resultant Mines Act of 1842 were meant to prevent women and boys under 10 years of age from working underground, it is believed they were widely ignored. To replace female and child labour the pit pony was more widely introduced. Much later, in the middle of the 20th century, mining was still a hazardous enterprise, resulting in many accidents and long term ill-health with many retired miners still suffering from silicosis and other mining related diseases.

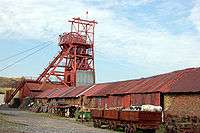

Incorporating the existing Coity colliery and Kearsley's pit (sunk in 1860), the Big Pit opened in 1880, so called because it was the first shaft in Wales large enough to allow two tramways. At the height of coal production, there were over 160 drift mines and over 30 shafts working the nine seams in the Blaenavon locality. Big Pit alone employed some 1,300 men digging a quarter of a million tons of coal a year. Large amounts of coal were needed to supply the local ironworks, as it took 3 tons of coal to produce a ton of iron. Blaenavon 'steam' coal was of high quality and it was exported globally. Burning hotly while leaving minimum ash, it was ideal to power the steam engines that drove steamships, Dreadnoughts of the Royal Navy and steam locomotive railways across the world.

However both economics and politics after World War I with its resultant general strike, the 1930s Depression and later Nationalisation and the miners' strike of 1984-1985 took their toll and all the smaller pits were either abandoned or swallowed into Big Pit's encroaching search for new seams. Finally in February 1980 the coal ran out and even Big Pit, then the oldest mine in Wales, had to close.

There are still nine headstocks remaining in Wales, including Big Pit (the metal frame erected in 1921 during the Miners' Strike of that year, to replace a wooden structure).

There is a well-known mining song part in Welsh and part in English.

I am a little collier and gweithio underground

The raff will never torri when I go up and down

It's bara when I'm hungry

And cwrw when I'm dry

It's gwely when I'm tired

And nefoedd when I die

The complete English translation is the following.

I am a little collier and working underground

The rope will never break when I go up and down

It's bread when I'm hungry

And beer when I'm dry

It's bed when I'm tired

And heaven when I die

Big Pit National Coal Museum & other mining museums in Wales

The Big Pit National Coal Museum is located at Blaenavon, and in 2005 it won the prestigious Gulbenkian Prize for museum of the year. It is one of only two remaining mines where it is possible for visitors to journey to the underground workings some 300 ft (90 m) below using the same cages that transported the miners.

Other museums preserving the memories and heritage of the coal mining industry in Wales are at :

Slate quarrying

There has been slate quarrying in Wales since the Roman period, when slate was used to roof the fort at Segontium, now Caernarfon. The slate industry grew slowly until the early 18th century, then expanded rapidly until the late 19th century, at which time the most important slate producing areas were in northwest Wales, including the Penrhyn Quarry near Bethesda, the Dinorwic Quarry near Llanberis, the Nantlle Valley quarries, and Blaenau Ffestiniog, where the slate was mined rather than quarried. Penrhyn and Dinorwig were the two largest slate quarries in the world, and the Oakeley mine at Blaenau Ffestiniog was the largest slate mine in the world.[3] Slate is mainly used for roofing, but is also produced as thicker slab for a variety of uses including flooring, worktops and headstones.[4]

The slate industry in North Wales is on the tentative World Heritage Site list[5] whilst Welsh slate has been designated by the International Union of Geological Sciences as a Global Heritage Stone Resource.[6]

Metal mining

Metal mining in Wales affected large areas of what are now very rural parts of Wales and left behind a legacy of contaminated waste heaps and a very few ruined buildings.

There are a number of areas that have been mined for a variety of metals.

[In Wales,]

Valeys bryngeþ forþ food,

And hilles metal riȝt good

Gold mining

Gold was mined as early as the Roman period at Dolaucothi in Carmarthenshire and possibly elsewhere. In the 19th century gold was being extracted from a number of small mines at the southern end of Snowdonia with most activity centred in the valley of the River Mawddach and its tributaries.

Lead and silver

The principal areas were centred on the upland areas of the River Ystwyth and River Rheidol with some outliers to the east in the catchment of the River Severn and some to the south in the headwaters of the River Teifi. The largest of these mines were the Cwmystwyth and Rheidol United mines in Cwm Rheidol. The ore extracted was galena which in many cases had a high silver content, especially at Cwm Ystwyth. It also occurred alongside large quantities of sphalerite, the principal ore of zinc. However, the zinc was only occasionally processed and much remains on the very extensive discard heaps around the mines.

Amongst the very many mines that have existed the following list identifies those known to have existed between the 17th and 19th centuries in north Cardiganshire and west Montgomeryshire:

Aberffrwd, Alma, Blaenceunant, Blaencwmsymlog, Bron floyd, Bryn Glas, Bwa Drain, Bwlch, Cwm Mawr, Cwmystwyth, Cwm Ystwyth South, Cwm Ystwyth West, Cwmbryno, Cwmdarren, Cwmsymlog, De Broke, Dyffryn Castell, Elgar, Esgair Lle, Esgairmwyn, Fron Goch, Fron Goch East, Gelli, Glog fach, Glog Fawr, Goginan, Goginan west, Graig Goch, Grogwynion, Gwaith coch, Lisburne South, Llwynmalus, Llywernog, Logau Las, Melindwr, Mynyddgorddu, Nanteos, Pen Rhiw, Powell, Rheidol United, Temple, Ystumtuen

Metal mining in the Gwydir Forest dates back to the 17th century, but its heyday came in the latter half of the 19th century. These mines predominantly produced lead and zinc, and the last mine to close – Park Mine – closed in the 1960s.[8]

Smaller areas of lead exploitation included Halkyn Mountain in Flintshire and in the Clyne valley in west Swansea.

Copper

Copper mining is probably the oldest known mining activity in Wales with documented evidence of Bronze Age mining on the Great Orme near Llandudno and at Copa Hill in the valley of the River Ystwyth in Ceredigion. Further copper discoveries were exploited in Snowdonia just to the east of Beddgelert where the Sygun Copper Mine, within the Snowdonia National Park, gives an idea of the conditions faced by copper miners and is a popular tourist attraction. In the 18th century the massive deposits of copper together with a range of other metals was discovered and exploited at Parys Mountain on Anglesey.

Iron

Commercial iron ore exploitation has been relatively uncommon in Wales during the last hundred years, despite the dominance of the iron and steel industry in South Wales. However ironstone is a component of the Lower Coal Measures rock sequence and where it outcrops along the northern edge of the South Wales Coalfield, it was extensively worked for the production of iron and was important in the initiation of the Industrial Revolution in South Wales.[9] Commercial exploitation also took place in the Vale of Glamorgan. The Forest of Dean was an important source of iron for many centuries, and dates from at least the Roman period.

Lead

Lead ore was first mined in North Wales during Roman times at Pentre Halkyn to be smelted at Flint. The lead that was produced there was stamped with the inscription Deceangli, which was the name of the Celtic tribe occupying the area. In the 17th century an intensive period of Welsh lead mining commenced, bringing a large number of miners from Derbyshire into Wales. There are substantial reserves of the metal in Ceredigion, probably first exploited in the Roman period, and extensively during the revival of metal mining in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

Arsenic

Arsenic has been mined in association with metals and in Wales commercial extraction has probably only occurred in the Clyne valley near Swansea.

Working mines

Following the miners' strike, only two deep mines remained working in Wales. Tower Colliery, Hirwaun, had been run by a miner's co-operative since 1994. Due to dwindling coal seams, the colliery was last worked on 18 January 2008, followed by official closure on 25 January.[10] Drift mining continued at Aberpergwm Colliery, a smaller mine closed by the National Coal Board in 1985 but reopened in 1996. Aberpergwm colliery is currently owned and operated by Energybuild and supplies the carbon market.[11] Several other small mines still exist, including the Blaentillery drift mine near to the Big Pit National Coal Museum.

List of mines in Wales

Coal

- Abercynon Colliery

- Abernant Colliery

- Aberpergwm (anthracite coal, drift mine, active in 2014 with 64 employees (closed)

- Albion Colliery in Cilfynydd, Pontypridd - work began 1884 and the mine closed in 1966[12]

- Bedwas Navigation Colliery (closed 1985)

- Bersham Colliery (closed 1986)

- Big Pit National Coal Museum

- Blaenant Colliery (closed 1990)

- Bute Merthyr Colliery

- Bwllfa Colliery

- Cambrian Colliery

- Cefn Coed Colliery Museum

- Celynen North Colliery in Newbridge

- Celynen South Colliery in Abercarn (closed 1985)

- Coedely Colliery Ttonyrefail (closed 1985); linked underground to Cwm Colliery Beddau (closed 1986)

- Cynheidre Colliery (closed 1989)

- Deep Navigation Colliery, Treharris (closed 1991)

- Ferndale Colliery

- Ffos-y-fran Land Reclamation Scheme (still under consideration as of 2013)

- Garw/Ffaldau Colliery

- Gresford Colliery (closed 1973)

- Great Western Mine

- Hafodyrynys Colliery

- Lady Windsor Colliery in Ynysybwl (closed 1988); linked underground to Abercynon Colliery (Closed 1988)

- Llancaiach Colliery

- Mardy Colliery in Maerdy (closed 1990, site cleared and now occupied by Avon Rubber); linked underground to Tower Colliery

- Marine Colliery in Cwm, Blaenau Gwent, merged with Six Bells Colliery in the 1970s, closed in 1989

- Mostyn Colliery (closed 1887 after flooding)

- Nantgarw Colliery (amalgamated with Windsor Colliery in 1974, closed 1986); deepest pit in the South Wales Coalfield when sunk in 1915

- Navigation Colliery in Crumlin

- Nine Mile Point Colliery at Cwmfelinfach (closed 1964)

- Oakdale Colliery at Ty Mellyn in the Sirhowy Valley (closed 1989; linked to Markham and Celynen North)

- Parc Slip Colliery

- Penallta Colliery

- Pentremawr Colliery

- Prince of Wales Colliery in Abercarn closed 1959. Greatest mining disaster in Monmouthshire, 1878.

- Point of Ayr (closed 1996)

- Primrose Colliery

- Seven Sisters anthracite; closed 1963

- Six Bells Colliery in Abertillery, site of the Six Bells Colliery Disaster in 1960, merged with Marine Colliery in the 1970s, closed in 1988

- Taff Merthyr

- Tarenni Colliery

- Tower Colliery (closed 1994 and re-opened after an employees' buy-out by Goitre Tower Anthracite in 1995; closed 2008 after exhaustion of the seam, but with plans to build an open-cast mine in its place)

- Universal Colliery at Senghenydd, site of the Senghenydd Colliery Disaster; converted to a ventilation facility for Windsor Colliery and then closed in 1988

- Windsor Colliery in Abertridwr, Caerphilly; closed 1986

- Wyllie Colliery in the Sirhowy Valley; closed 1968

Metal ores

- Bryntail lead mine (No longer in use)

- Cilcain lead mine (No longer in use)

- Clogau Gold Mine

- Cwmystwyth Mines

- Dolaucothi Gold Mines

- Great Orme copper

- Gwydir Forest various metal mines

- Gwynfynydd gold mine (No longer in use)

- Klondyke mine lead mine (No longer in use)

- Llywernog Mine silver-lead mine

- Minera Leadmines (No longer in use)

- Parys Mountain copper mine

- Sygun Copper Mine (No longer in use as a mine)

- Van Leadmine Llanidloes

- Penrhyn Du mines (no longer in use)

Popular Culture

The theme of Public Service Broadcasting's third album, Every Valley, follows the rise and fall of Welsh coal mining. It was recorded in the former steelworks town of Ebbw Vale, Wales, and released on 7 July 2017.

See also

References

- Jones, Barri; Mattingly, David (1990), "The Economy", An Atlas of Roman Britain, Cambridge: Blackwell Publishers (published 2007), pp. 175–195, ISBN 978-1-84217-067-0

- The History of the Parishes of Whiteford and Holywell; Thomas Pennant, 1796, p.133

- Jones, R. Merfyn (1981). "The North Wales Quarrymen, 1874–1922". Studies in Welsh History. University of Wales Press. 4: 72. ISBN 0-7083-0776-0.

- Lindsay, Jean (1974). A History of the North Wales Slate Industry. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. p. 133. ISBN 0-7153-6264-X.

- "Tentavive World Heritage Site List UK". Unesco.org. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- "Designation of GHSR". IUGS Subcommission: Heritage Stones. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- Higden, Ranulf (1865) [First published 1387]. Babington, Churchill (ed.). Polychronicon. Translated by Trevisa, John. London: Longman. p. 399. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- mindat.org

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-02-10. Retrieved 2012-01-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Blaenavon Ironworks information

- "Coal mine closes with celebration". BBC News. 2008-01-25. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- "Jobs to go as South West Wales coal mine is mothballed". South Wales Evening Post. 2015-06-26. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- "Albion Colliery". BBC Wales. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

Further reading

- Benson, John. British Coal-Miners in the Nineteenth Century: A Social History (Holmes & Meier, 1980)

- Berger, Stefan Llafur. "Working-Class Culture and the Labour Movement in the South Wales and the Ruhr Coalfields, 1850-2000: A Comparison," Journal of Welsh Labour History/Cylchgrawn Hanes Llafur Cymru (2001) 8#2 pp 5-40.

- Curtis, Ben. The South Wales Miners, 1964-1985 (University of Wales Press, distributed by University of Chicago Press; 2013) 301 pages

- Curtis, Ben. "A Tradition of Radicalism: The Politics of the South Wales Miners, 1964-1985," Labour History Review (2011) 76#1 pp 34-50

External links

- Welsh Coal Mines - all the Welsh pits and their brief histories

- BBC Wales Coal House website

- 42 pages of mining photos compiled by John Cornwell and held on Gathering the Jewels

- Coal Mining in Blaenavon

- North, F. J. (1962). Mining for Metals in Wales (PDF). Cardiff: National Museum of Wales. ISBN 978-0720000214.

- AditNow – Photographic database of mines

- Welsh Mines Society – Society with a focus on the research, recording and exploration of the metal mines of Wales