Midway (1976 film)

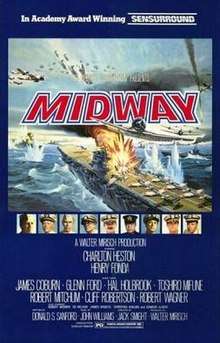

Midway, released in the United Kingdom as Battle of Midway, is a 1976 American Technicolor war film directed by Jack Smight and produced by Walter Mirisch from a screenplay by Donald S. Sanford.[2][3] The film features an international cast of stars including Charlton Heston, Henry Fonda, James Coburn, Glenn Ford, Ed Nelson, Hal Holbrook, Toshiro Mifune, Robert Mitchum, Cliff Robertson, Robert Wagner, James Shigeta, Pat Morita, John Fujioka, Robert Ito and Christina Kokubo.

| Midway | |

|---|---|

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jack Smight |

| Produced by | Walter Mirisch |

| Written by | Donald S. Sanford |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Williams |

| Cinematography | Harry Stradling Jr. |

| Edited by |

|

Production company | The Mirisch Corporation |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 131 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The music score by John Williams and the cinematography by Harry Stradling Jr. were both highly regarded. The soundtrack used Sensurround to augment the physical sensation of engine noise, explosions, crashes and gunfire. Despite mixed reviews, Midway became the tenth most popular movie at the box office in 1976.

Plot

The film chronicles the Battle of Midway, a turning point in World War II in the Pacific. The Imperial Japanese Navy had been undefeated until that time and out-numbered the American naval forces by four to one. It follows two threads; one centered on the Japanese chief strategist Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, and the other on naval aviators Captain Matt Garth and his son, Ensign Thomas Garth.

The film starts with the Doolittle Raid (April 1942), and then goes on briefly to mention the Battle of the Coral Sea (May 1942). It then describes the planning for the Battle of Midway (June 1942), depicting the creation of a complicated battle plan. Unknown to the Japanese, American signals intelligence has broken the Japanese Naval encryption codes and suspects that the ambush will take place at Midway Island. They then trick the Japanese into confirming it. Senior officer Matt Garth is involved in various phases of the US planning and execution of the battle, while pilot Thomas Garth is romantically involved with Haruko Sakura, an American-born daughter of Japanese immigrants, who has been interned with her parents. Captain Garth calls in all of his favors with a long-time friend to investigate the charges against the Sakuras. American Admiral Chester Nimitz plays a desperate gamble by sending his last remaining aircraft carriers to Midway before the Japanese to set up his own ambush. The gamble pays off and all four of the Japanese carriers are destroyed in the battle of Midway. Captain Garth himself is killed at the end of the battle when his plane crashes, while the injured younger Garth is carried off the ship, seen by a free Haruko at the dockside.

Successful in saving Midway, but at a heavy cost, Nimitz reflects that Yamamoto "had everything going for him", asking "were we better than the Japanese, or just luckier?"

Cast

- Charlton Heston as Captain Matthew Garth

- Henry Fonda as Admiral Chester W. Nimitz

- James Coburn as Captain Vinton Maddox

- Glenn Ford as Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance

- Hal Holbrook as Commander Joseph Rochefort

- Toshiro Mifune (voiced by Paul Frees) as Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto

- Robert Mitchum as Vice Admiral William F. "Bull" Halsey Jr.

- Cliff Robertson as Cmdr. Carl Jessop

- Robert Wagner as Lieutenant Commander Ernest L. Blake

- Robert Webber as Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher

- Ed Nelson as Rear Admiral Harry Pearson

- James Shigeta as Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo

- Christina Kokubo as Haruko Sakura

- Monte Markham as Cmdr. Max Leslie

- Biff McGuire as Captain Miles Browning

- Christopher George as Lieutenant Commander C. Wade McClusky

- Kevin Dobson as Ensign George H. Gay Jr.

- Glenn Corbett as Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron

- Gregory Walcott as Captain Elliott Buckmaster

- Edward Albert as Lieutenant Thomas Garth

- Pat Morita as Rear Admiral Ryūnosuke Kusaka

- John Fujioka as Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi

- Dale Ishimoto as Vice Admiral Boshirō Hosogaya

- Dabney Coleman as Captain Murray Arnold

- Erik Estrada as Ensign Ramos "Chili Bean"

- Larry Pennell as Captain Cyril Simard

- Clyde Kusatsu as Cmdr. Watanabe Yasimasa

- Phillip R. Allen as Lieutenant Commander John S. "Jimmy" Thach

- Tom Selleck as Aide to Capt. Cyril Simard

- Sab Shimono as Lt. Jōichi Tomonaga

- Conrad Yama as Admiral Nobutake Kondō

- Robert Ito as Commander Minoru Genda

- Seth Sakai as Captain Kameto Kuroshima

- Kurt Grayson as Major Floyd "Red" Parks

- Steve Kanaly as Lt. Cmdr. Lance E. Massey

Production

Filming

Midway was shot at the Terminal Island Naval Base, Los Angeles, California, the U.S. Naval Station, Long Beach, California, and Naval Air Station Pensacola, Florida. The on-board scenes were filmed in the Gulf of Mexico aboard USS Lexington. Lexington, an Essex-class aircraft carrier, was the last World War II-era carrier left in service at that point, although the ship was completed after the battle. She is now a museum ship at Corpus Christi, Texas.

Scenes depicting Midway Island were filmed at Point Mugu, California. "Point Mugu has sand dunes, just like Midway. We built an airstrip, a tower, some barricades, things like that," said Jack Smight. "We did a lot of strafing and bombing there."[4]

A Consolidated PBY-6A Catalina BuNo 63998, N16KL, of the Commemorative Air Force, was used in depicting all the search and rescue mission scenes.

Sound

The film was the second of only four films released with a Sensurround sound mix which required special speakers to be installed in movie theatres. The other Sensurround films were Earthquake (1974), Rollercoaster (1977), and Battlestar Galactica (1978). The regular soundtrack (dialog, background and music) was monaural; a second optical track was devoted to low frequency rumble added to battle scenes and when characters were near unmuffled military engines.

Action

Many of the action sequences used footage from earlier films: most sequences of the Japanese air raids on Midway are stock shots from 20th Century Fox's Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970). Some scenes are from the Japanese Toho film Hawai Middouei daikaikusen: Taiheiyo no arashi (1960) (which also stars Mifune). Several action scenes, including the one where a Mitsubishi A6M Zero slams into Yorktown's bridge, were taken from Away All Boats (1956); scenes of Doolittle's Tokyo raid at the beginning of the film are from Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo (1944). In addition, most dogfight sequences come from wartime gun camera footage or from the film Battle of Britain (1969).

Cast member Henry Fonda (Admiral Nimitz) had been one of the narrators of the 1942 John Ford documentary The Battle of Midway, some footage from which was used in the 1976 film. This was the third film dealing with the aftermath of Pearl Harbor with which Henry Fonda had been involved. Henry first narrated the 1942 film The Battle of Midway and starred in the 1965 film In Harm's Way. The only actress with a speaking part in the original film was Christina Kobuko as Horuko. In the TV version of the film Susan Sullivan appears playing Matt Garth's girlfriend. Later video versions dropped Sullivan to emphasize the essentially all-male cast and wartime action.

_screenshot.jpg)

As with many "carrier films" produced around this time, the US Navy Essex-class aircraft carriers USS Lexington and USS Boxer played the parts of both American and Japanese flattops for shipboard scenes.

Reception

Box Office

Midway proved extremely popular with movie audiences, earning over $43 million at the box office, becoming the tenth most popular movie of 1976.

Variety said the film earned $20,300,000 in 1976.[5]

Critical response

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote, "The movie can be experienced as pure spectacle, I suppose, if we give up all hopes of making sense of it. Bombs explode and planes crash and the theater shakes with the magic of Sensurround. But there's no real directorial intelligence at hand to weave the special effects into the story, to clarify the outlines of the battle and to convincingly account for the unexpected American victory."[6] Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that "the movie blows up harmlessly in a confusion of familiar old newsreel footage, idiotic fiction war movie clichés, and a series of wooden-faced performances by almost a dozen male stars, some of whom appear so briefly that it's like taking a World War II aircraft-identification test."[7] Arthur D. Murphy of Variety thought that the film "emerges more as a passingly exciting theme-park extravaganza than a quality motion picture action-adventure story ... Donald S. Sanford's cluttered script, while striving for the long-ago personal element, gets overwhelmed by its action effects."[8] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film two-and-a-half stars out of four and wrote that "[t]he battle scenes run hot and cold." He praised Henry Fonda as "absolutely convincing" but stated that Sanford "deserves a year in the brig for inserting amid the battle scenes a stupid subplot involving a young American sailor in love with a Japanese-American girl."[9] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post called it a "tired combat epic" and wrote, "Hollywood may mean well, or imagine it does, but it's a little appalling to think that authentic acts of bravery and sacrifice have become the pretext for such feeble, inadequate dramatization. There is no serious attempt in 'Midway' to characterize the young men who fought on either side of this pivotal battle."[10] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times was mixed, describing it as "a disaster film whose disaster is war," with its principal strength being that it "keeps the lines of battle both straight and suspenseful in the viewer's mind." He too faulted the romance subplot as "hokey even beyond the demands of the form."[11] Janet Maslin panned the film in Newsweek, stating that it "never quite decides whether war is hell, good clean fun, or merely another existential dilemma. This drab extravaganza toys with so many conflicting attitudes that it winds up reducing the pivotal World War II battle in the Pacific to utter nonsense."[12]

Robert Niemi, author of History in the Media: Film and Television, stated that Midway's "clichéd dialogue" and an overuse of stock footage led the film to have a "shopworn quality that signalled the end of the heroic era of American-made World War II epics." He described the film as a "final, anachronistic attempt to recapture World War II glories in a radically altered geopolitical era, when the old good-versus-evil dichotomies no longer made sense."[13]

Later studies by Japanese and American military historians call into question key scenes, like the dive-bombing attack that crippled the first Japanese carrier, the Akagi. In the movie, American pilots report, "They've got bombs all over their flight deck! We caught 'em flat-footed! No fighters and a deck full of bombs!" As Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully write in "Shattered Sword" (2005), aerial photography from the battle showed nearly empty decks. In addition, Japanese carriers loaded armament onto planes below the flight deck, unlike American carriers (as depicted earlier in the film). The fact that a closed hangar full of armaments was hit by bombs made damage to Akagi more devastating than if planes, torpedoes and bombs were on an open deck.[14]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 54% score based on 13 reviews, with an average rating of 5.9/10.[15]

Television version

Shortly after its successful theatrical debut, additional material was assembled and shot in standard 4:3 ratio for a TV version of the film, which aired on NBC.[16][17] A major character was added: Susan Sullivan played Ann, the girlfriend of Captain Garth, adding depth to his reason for previously divorcing Ensign Garth's mother, and bringing further emotional impact to the fate of Captain Garth. The TV version also has Coral Sea battle scenes to help the plot build up to the decisive engagement at Midway. The TV version was 45 minutes longer than the theatrical film and aired over two nights. Mitchell Ryan was added as Rear Admiral Aubrey W. Fitch.[18] Jack Smight directed the additional scenes.[16]

In June 1992, a re-edit of the extended version, shortened to fill a three-hour time slot, aired on the CBS network to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Midway battle. This version brought in successful ratings.[16]

Part of this additional footage is available as a bonus feature on the Universal Pictures Home Entertainment DVD of Midway.

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2006: AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – Nominated[19]

Historical accuracy

The plot follows the real battle remarkably well. Even though simplified, omitting details here and there did not distort the story. Such details, among others, were reduced:

- More flag officers took part at the decision making and planning before the battle, not just Nimitz, Fletcher and Spruance. All the same, commanding officers' staffs were generally bigger than the one or two men portrayed in the movie.

- Admiral King, commander-in-chief of the navy at that time, approved the Midway battle plan propounded by Nimitz. They were regularly in contact, so there was no need of sending fictional Capt. Vinton Maddox to consult Nimitz (apart from enabling James Coburn to star in the movie).

- There were numerous air attacks by Midway-based bombers on approaching Japanese fleets completely omitted in the script. However, these had the same effect as later carrier-based torpedo bombers decimated by Japanese fleet air-defenses portrayed in the movie. Lack of impact from initial raids by land-based bombers only convinced Japanese commanders of their invincibility and incompetency of US military.[20]

While most characters portray real persons, some of them are fictional though inspired by actual people. Captain Matt Garth and his son, Ensign Thomas Garth, are both fictional characters. Captain Matthew Garth's contribution to planning the battle is based rather faithfully on actual work of Lieutenant-Commander Edwin Layton. Layton served as Pacific fleet intelligence officer. He spoke Japanese and was key to transposing raw outputs of cryptography analysis into meaningful intelligence for Nimitz and his staff. Layton was long-time friend of Joseph Rochefort. Matt Garth's further exploits were pure fiction and resembled deeds of at least two more persons. First, an intelligence officer at Adm. Fletcher's Task Force 17 staff and then the leader of the last attack made by dive bombers from USS Yorktown. The latter, however, was actually performed by VB-3 dive bomber squadron led by LCDR Maxwell Leslie. Matt Garth's character thus combine three actual people involved in the battle. While this is reasonable for the sake of storytelling, it could not have happened as it was unimaginable to put such a valuable officer as fleet intelligence officer in harm's way. Besides, Layton was not a flyer.

Historical footage and atelier shots of warplanes action are mostly inaccurate in the movie. Most of the original footage portrays later and/or different events and thus planes and ships that were not operational during the battle or did not take part. One of the most flagrant moments is Matt Garth's collision at the very end of the movie, which is followed by the recording of a post-war jet plane crash which actually occurred on USS Midway. Like the USS Lexington used in filming, USS Midway is also preserved as a museum.

See also

- List of historical drama films

- List of historical drama films of Asia

- Midway (2019 film)

References

- "MIDWAY (A)". British Board of Film Classification. April 23, 1976. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- Variety film review; June 16, 1976, page 18.

- Harrison, Alexa (February 15, 2011). "'Midway' writer Donald S. Sanford dies at 92". Variety. United States: Variety Media, LLC. (Penske Media Corporation). Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- Newspaper Enterprise Association, "Filming of 'Midway': Making War for the Movies", Playground Daily News, Fort Walton Beach, Florida, Wednesday 8 October 1975, Volume 30, Number 209, page 5B.

- SECOND ANNUAL GROSSES GLOSS Byron, Stuart. Film Comment; New York Vol. 13, Iss. 2, (Mar/Apr 1977): 35-37,64.

- Ebert, Roger (June 22, 1976). "Midway". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved December 12, 2018.

- Canby, Vincent (June 19, 1976). "On Film, the Battle of 'Midway' Is Lost". The New York Times. 11.

- Murphy, Arthur D. (June 16, 1976). "Film Reviews: Midway". Variety. 18.

- Siskel, Gene (June 21, 1976). "Decisive U.S. sea battle flounders in Hollywood". Chicago Tribune. Section 3, p. 4.

- Arnold, Gary (June 19, 1976). "Bombs Away". The Washington Post. B1, B7.

- Champlin, Charles (June 18, 1976). "'Earthquake' Goes to Sea". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- Maslin, Janet (June 28, 1976). "Sinking Ship". Newsweek. 78.

- Niemi, Robert. History in the Media: Film and Television.ABC-CLIO, 2006, p. 119. Retrieved on April 9, 2009.

- Jonathan Parshall and Anthony Tully (2005). "Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway" (pp. 431-432). Potomac Books, Washington, DC. ISBN 978-1-57488-924-6.

- "Midway (1976)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- Mirisch, Walter (2008). I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 338–339. ISBN 978-0299226404..

- "Midway". Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "Midway". MCA Home Video. Los Angeles: Universal Pictures Home Entertainment. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- 1910-1980., Prange, Gordon W. (Gordon William) (1982). Miracle at Midway. Goldstein, Donald M., Dillon, Katherine V. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070506728. OCLC 8552795.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

- Midway on IMDb

- Midway at the TCM Movie Database

- Midway at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Midway at Rotten Tomatoes