Menhaden

Menhaden, also known as mossbunker and bunker, are forage fish of the genera Brevoortia and Ethmidium, two genera of marine fish in the family Clupeidae. Menhaden is a blend of poghaden (pogy for short) and an Algonquian word akin to Narragansett munnawhatteaûg, derived from munnohquohteau ("he fertilizes"), referring to their use of the fish as fertilizer.[1] It is generally thought that Pilgrims were advised by Tisquantum (also known as Squanto) to plant menhaden with their crops.[1]

| Menhaden | |

|---|---|

| |

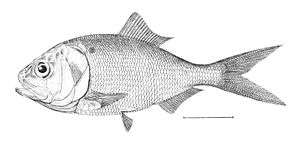

| Brevoortia patronus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Clupeiformes |

| Family: | Clupeidae |

| Groups included | |

| |

| Cladistically included but traditionally excluded taxa | |

|

all other genera in the family Clupeidae | |

Description

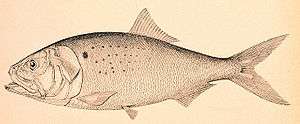

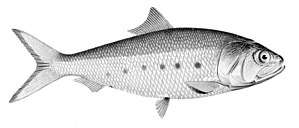

Menhaden are flat and have soft flesh and a deeply forked tail. They rarely exceed 15 inches (38 cm) in length, and have a varied weight range. Gulf menhaden and Atlantic menhaden are small oily-fleshed fish, bright silver, and characterized by a series of smaller spots behind the main, humeral spot. They tend to have larger scales than yellowfin menhaden and finescale menhaden. In addition, yellowfin menhaden tail rays are a bright yellow in contrast to those of the Atlantic menhaden.

Taxonomy

| This article is part of a series on |

| Commercial fish |

|---|

| Large pelagic |

| Forage |

| Demersal |

| Mixed |

Recent taxonomic work using DNA comparisons have organized the North American menhadens into large-scaled (Gulf and Atlantic menhaden) and small-scaled (Finescale and Yellowfin menhaden) designations.[2]

The menhaden consist of two genera and seven species:

- Genus Brevoortia T. N. Gill, 1861

- Brevoortia aurea (Spix & Agassiz, 1829) (Brazilian menhaden)

- Brevoortia gunteri Hildebrand, 1948 (Finescale menhaden)

- Brevoortia patronus Goode, 1878 (Gulf menhaden)

- Brevoortia pectinata (Jenyns, 1842) (Argentine menhaden)

- Brevoortia smithi Hildebrand, 1941 (Yellowfin menhaden)

- Brevoortia tyrannus (Latrobe, 1802) (Atlantic menhaden)

- Genus Ethmidium W. F. Thompson, 1916

- Ethmidium maculatum (Valenciennes, 1847) (Pacific menhaden)

Distribution

- Finescale menhaden range from the Yucatán to Louisiana

- Yellowfin menhaden range from Louisiana to Virginia

- Gulf menhaden range from the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico to Tampa Bay, Florida

- Atlantic menhaden range from Jupiter Inlet, Florida, to Nova Scotia; Atlantic menhaden seasonally migrate along the coast; in June, mature adults typically are in the northern portion of the coastline with sub-adults and juveniles located in the southern portion

- The various species of menhaden occur anywhere from estuarine waters outward to the continental shelf; menhaden grow in less saline waters of estuaries and may be found in bays and lagoons, as well as at river mouths; adults appear to prefer water temperatures near 18 °C

Ecology

Menhaden are filter feeders that travel in large, slow-moving, and tightly-packed schools with open mouths. Filter feeders typically take into their open mouths "materials in the same proportions as they occur in ambient waters".[3] Menhaden have two main sources of food: phytoplankton and zooplankton. A menhaden's diet varies considerably over the course of its lifetime, and is directly related to its size. The smallest menhaden, typically those under one year old, eat primarily phytoplankton. After that age, adult menhaden gradually shift to a diet comprised almost exclusively of zooplankton.[4]

Menhaden are omnivorous filter feeders, feeding by straining plankton and algae from water. Along with oysters, which filter water on the seabed, menhaden play a key role in the food chain in estuaries and bays.[5] Atlantic menhaden are an important link between plankton and upper level predators. Because of their filter feeding abilities, "menhaden consume and redistribute a significant amount of energy within and between Chesapeake Bay and other estuaries, and the coastal ocean."[6] Because they play this role, and their abundance, menhaden are an invaluable prey species for many predatory fish, such as striped bass, bluefish, mackerel, flounder, tuna, drums, and sharks. They are also a very important food source for many birds, including egrets, ospreys, seagulls, northern gannets, pelicans, and herons.

In 2012, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission declared that the Atlantic menhaden was depleted due to overfishing. The decision was driven by issues with water quality in the Chesapeake Bay and failing efforts to re-introduce predator species, due to lack of menhaden on which they could feed.[1]

Human intake

Menhaden are not used directly for food. They are processed into fish oil and fish meal that are used as food ingredients, animal feed, and dietary supplements.[5] The flesh has a high omega-3 fat content. Fish oil made from menhaden also is used as a raw material for products such as lipstick.[7]

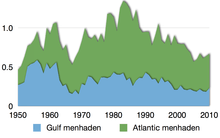

Fisheries

According to the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), there are two established commercial fisheries for menhaden. The first is known as a reduction fishery. The second is known as a bait fishery, which harvests menhaden for the use of both commercial and recreational fishermen. Commercial fishermen, especially crabbers in the Chesapeake Bay area, use menhaden to bait their traps or hooks. The recreational fisherman use ground menhaden chum as a fish attractant, and whole fish as bait. The total harvest is approximately 500 million fish per year.[7] Atlantic menhaden are harvested using purse seines.

Omega Protein – a reduction fishery company with operations in the northwest Atlantic and the Gulf of Mexico – takes 90% of the total menhaden harvest in the United States.[7] In October 2005, the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) approved an addendum to Amendment 1 of the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Menhaden, which "established a five-year annual cap on reduction fishery landings in the Chesapeake Bay", imposing a limit on reduction fishery operations for 2006–2010. In November 2006, that cap was established at 109,020 metric tons;[9] this cap remained in place until 2013.[10]

In December 2012, in the face of the depletion of Atlantic menhaden, the ASMFC implemented another cap, effective in 2013 and 2014, for the Chesapeake Bay, this time at 87,216 metric tons, as well as a total allowable catch (TAC) of the species of 170,800 metric tons, a 20% reduction from the 2009–2011 average.[11][12] The TAC was subsequently raised for 2015 and 2016 to 187,880 metric tons.[13] The cap in the Chesapeake Bay was further lowered in November 2017 to 51,000 metric tons, but this came alongside a higher TAC of 216,000 metric tons.[14][15] Omega Protein has been openly critical of these caps.[12][15]

Cultural significance

After menhaden had been identified as a valuable alternative to whale oil in the 1870s, the menhaden fishery on the Chesapeake was worked by predominantly African American crews on open boats hauling purse seines. The men employed sea chanties to help synchronize the hauling of the nets. These chanties pulled from West African, blues, and gospel sources and created a uniquely African American culture of chanty singing. By the late 1950s, hydraulic winches replaced the large crews of manual haulers, and the menhaden chanty tradition declined.[16]

Notes

- Conniff, Richard (7 December 2012). "The Oiliest Catch". Conservation Magazine. University of Washington. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Anderson, Joel D. (2007). "Systematics of the North American menhadens: molecular evolutionary reconstructions in the genus Brevoortia (Clupeiformes: Clupeidae)" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 105 (3): 368–378. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- VanderKooy, Steven J.; Smith, Joseph W., eds. (March 2002). The Menhaden Fishery of the Gulf of Mexico, United States: A Regional Management Plan (PDF) (Report). Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission. pp. 3–10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2019.

- Friedland, Kevin D.; Lynch, Patrick D.; Gobler, Christopher J. (November 2011). "Time Series Mesoscale Response of Atlantic Menhaden Brevoortia tyrannus to Variation in Plankton Abundances". Journal of Coastal Research. 27 (6): 1148–1158. doi:10.2112/JCOASTRES-D-10-00171.1.

- Tavee, Tom; Franklin, H. Bruce (1 September 2001). "The Most Important Fish in the Sea". Discover. Archived from the original on 8 August 2018.

- "Maryland Department of Natural Resources". Dnr.state.md.us. 31 December 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2013.

- Greenberg, Paul (15 December 2009). "A Fish Oil Story". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2019. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

- Based on data sourced from the relevant FAO Species Fact Sheets

- Addendum III to Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Menhaden (PDF) (Report). Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. November 2006. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- Addendum IV to Amendment 1 to the Atlantic Menhaden Fishery Management Plan (PDF) (Report). Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. November 2009. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2019.

- Amendment 2 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Menhaden (PDF) (Report). Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. December 2012. pp. 47, 55. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2019.

- Fairbrother, Alison (31 March 2013). "Omega Protein makes good on threat to cut jobs; but it doesn't have to". Bay Journal. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017.

- Addendum I to Amendment 2 of the Atlantic Menhaden Interstate Fishery Management Plan (PDF) (Report). Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. August 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2019.

- Amendment 3 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan for Atlantic Menhaden (PDF) (Report). Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. November 2017. p. iii, v. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2019.

- Bittenbender, Steve (7 May 2018). "Omega Protein critical of ASMFC actions on Chesapeake menhaden". SeafoodSource. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- Anderson, Harold (January–February 2000). "Menhaden Chanteys: An African American Maritime Legacy" (PDF). Maryland Marine Notes. College Park, Maryland: Maryland Sea Grant College. 18 (1): 1–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2019.

References

- "Brevoortia". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 6 June 2006.

- Pauly, Daniel (2 November 2007). "Fisheries: Tales of a small, but crucial, fish" (PDF). Science. 318 (5851): 750–751. doi:10.1126/science.1147800. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Useful menhaden links". Menhaden Matter. Archived from the original on 16 May 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Atlantic Menhaden Management". Chesapeake Bay Program. Archived from the original on 26 April 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- Fote, Thomas P. (21 April 1997). Interactions of Striped Bass, Bluefish and Forage Species (Speech). Congressional Testimony. Jersey Coast Anglers Association. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- "Geartype Fact Sheets: Purse Seines". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United States. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- Kirkley, James E. (2006). The Economic Importance and Value of Menhaden in the Chesapeake Bay Region (Report). Gloucester Point, Virginia.

- "Management: Conflict & Competition". Menhaden Resource Council. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Maryland Fish Facts: Atlantic Menhaden". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. 5 April 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Mycobacteriosis: Frequently Asked Questions". Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Plankton". Enchanted Learning. Archived from the original on 23 May 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- "Save the Stripers: Menhaden Update". National Coalition for Marine Conservation. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- Southwich Associates, Inc.; Loftus, Andrew J. (February 2006). Menhaden Math: The Economic Impact of Atlantic Menhaden on Virginia’s Recreational and Commercial Fisheries (PDF) (Report). American Sportfishing Association; Coastal Conservation Association; National Coalition for Marine Conservation; Theodore Roosevelt Conservation Partnership. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

- Virginia Institute of Marine Science (2009). Several menhaden research projects, currently unpublished.

- Durbin, Ann G.; Durbin, Edward G. (September 1998). "Effects of Menhaden Predation on Plankton Populations in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island". Estuaries and Coasts. 21 (3): 449–465. doi:10.2307/1352843. JSTOR 1352843. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Smith, Nathan G.; Jones, Cynthia M. (2007). Final Report to the VMRC and RFAB: What is the cause of menhaden recruitment failure? Quantifying the role of striped bass predation (PDF) (Report). RF 05-01. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Lynch, Patrick D. (December 2007). Feeding ecology of the Atlantic menhaden (Brevoortia tyrannus) in Chesapeake Bay (PDF) (Master's thesis). Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Friendland, Kevin D.; Ahrenholz, Dean W.; Smith, Joseph W.; Manning, Maureen; Ryan, Julia (December 2006). "Sieving functional morphology of the gill raker feeding apparatus of Atlantic menhaden". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A: Ecological Genetics and Physiology. 305 (12): 974–985. doi:10.1002/jez.a.348. PMID 17041916.

- "Saving Striped Bass by Managing Menhaden". Keep America Fishing. Archived from the original on 6 April 2011.

- 2006 Stock Assessment Report for Atlantic Menhaden (PDF) (Report). Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. 26 September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2012.

- "Atlantic Menhaden". Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Menhaden Species Team (March 2011). Ecosystem-Based Fisheries Management in Chesapeake Bay: Atlantic Menhaden (PDF) (Report). College Park, Maryland: Maryland Sea Grant College. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2019.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Menhaden. |

- NOAA Fisheries | NMFS

- Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission | ASMFC

- Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission | GSMFC

.png)