Fish migration

Many types of fish migrate on a regular basis, on time scales ranging from daily to annually or longer, and over distances ranging from a few metres to thousands of kilometres. Fish usually migrate to feed or to reproduce, but in other cases the reasons are unclear.

Migrations involve movements of the fish on a larger scale and duration than those arising during normal daily activities.[1] Some particular types of migration are anadromous, in which adult fish live in the sea and migrate into fresh water to spawn, and catadromous, in which adult fish live in fresh water and migrate into salt water to spawn.

Marine forage fish often make large migrations between their spawning, feeding and nursery grounds. Movements are associated with ocean currents and with the availability of food in different areas at different times of year. The migratory movements may partly be linked to the fact that the fish cannot identify their own offspring and moving in this way prevents cannibalism. Some species have been described by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea as highly migratory species. These are large pelagic fish that move in and out of the exclusive economic zones of different nations, and these are covered differently in the treaty from other fish.

Salmon and striped bass are well-known anadromous fish, and freshwater eels are catadromous fish that make large migrations. The bull shark is a euryhaline species that moves at will from fresh to salt water, and many marine fish make a diel vertical migration, rising to the surface to feed at night and sinking to lower layers of the ocean by day. Some fish such as tuna move to the north and south at different times of year following temperature gradients. The patterns of migration are of great interest to the fishing industry. Movements of fish in fresh water also occur; often the fish swim upriver to spawn, and these traditional movements are increasingly being disrupted by the building of dams.

Classification

As with various other aspects of fish life, zoologists have developed empirical classifications for fish migrations.[3] Two terms in particular have been in long-standing wide usage:

- Anadromous fish migrate from the sea up (Greek: ἀνά aná, "up" and δρόμος drómos, "course") into fresh water to spawn, such as salmon, striped bass,[4] and the sea lamprey[5]

- Catadromous fish migrate from fresh water down (Greek: κατά kata, "down" and δρόμος dromos, "course") into the sea to spawn, such as eels[4][6]

- Diadromous, amphidromous, potamodromous, oceanodromous. In a 1949 journal article, George S. Myers coined the inclusive term diadromous to refer to all fishes that migrate between the sea and fresh water. Like the two well known terms, it was formed from classical Greek ([dia], "through"; and [dromous], "running"). Diadromous proved a useful word, but terms proposed by Myers for other types of diadromous fishes did not catch on. These included amphidromous (fishes that migrate from fresh water to the seas, or vice versa, but not for the purpose of breeding), potamodromous (fishes whose migrations occur wholly within fresh water), and oceanodromous (fishes that live and migrate wholly in the sea).[3][7]

Although these classifications were originated for fishes, they are, in principle, applicable to any aquatic organism.

Forage fish

Forage fish often make great migrations between their spawning, feeding and nursery grounds. Schools of a particular stock usually travel in a triangle between these grounds. For example, one stock of herrings have their spawning ground in southern Norway, their feeding ground in Iceland, and their nursery ground in northern Norway. Wide triangular journeys such as these may be important because forage fish, when feeding, cannot distinguish their own offspring.

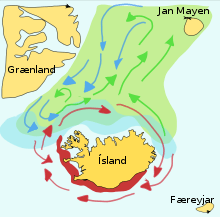

Capelin are a forage fish of the smelt family found in the Atlantic and Arctic oceans. In summer, they graze on dense swarms of plankton at the edge of the ice shelf. Larger capelin also eat krill and other crustaceans. The capelin move inshore in large schools to spawn and migrate in spring and summer to feed in plankton rich areas between Iceland, Greenland, and Jan Mayen. The migration is affected by ocean currents. Around Iceland maturing capelin make large northward feeding migrations in spring and summer. The return migration takes place in September to November. The spawning migration starts north of Iceland in December or January.[8]

The diagram on the right shows the main spawning grounds and larval drift routes. Capelin on the way to feeding grounds is coloured green, capelin on the way back is blue, and the breeding grounds are red.

In a paper published in 2009, researchers from Iceland recount their application of an interacting particle model to the capelin stock around Iceland, successfully predicting the spawning migration route for 2008.[9]

Highly migratory species

The term highly migratory species (HMS) has its origins in Article 64 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The Convention does not provide an operational definition of the term, but in an annex (UNCLOS Annex 1) lists the species considered highly migratory by parties to the Convention.[10] The list includes: tuna and tuna-like species (albacore, bluefin, bigeye tuna, skipjack, yellowfin, blackfin, little tunny, southern bluefin and bullet), pomfret, marlin, sailfish, swordfish, saury and oceangoing sharks, dolphins and other cetaceans.

These high trophic level oceanodromous species undertake migrations of significant but variable distances across oceans for feeding, often on forage fish, or reproduction, and also have wide geographic distributions. Thus, these species are found both inside the 200 mile exclusive economic zones and in the high seas outside these zones. They are pelagic species, which means they mostly live in the open ocean and do not live near the sea floor, although they may spend part of their life cycle in nearshore waters.[11]

Highly migratory species can be compared with straddling stock and transboundary stock. Straddling stock range both within an EEZ as well as in the high seas. Transboundary stock range in the EEZs of at least two countries. A stock can be both transboundary and straddling.[12]

Other examples

Some of the best-known anadromous fishes are the Pacific salmon species, such as Chinook (king), coho (silver), chum (dog), pink (humpback) and sockeye (red) salmon. These salmon hatch in small freshwater streams. From there they migrate to the sea to mature, living there for two to six years. When mature, the salmon return to the same streams where they were hatched to spawn. Salmon are capable of going hundreds of kilometers upriver, and humans must install fish ladders in dams to enable the salmon to get past. Other examples of anadromous fishes are sea trout, three-spined stickleback, sea lamprey and [5] shad.

Several Pacific salmon (Chinook, coho and Steelhead) have been introduced into the US Great Lakes, and have become potamodromous, migrating between their natal waters to feeding grounds entirely within fresh water.

The most remarkable catadromous fishes are freshwater eels of genus Anguilla, whose larvae drift from spawning grounds in the Sargasso sea, sometimes for months or years, before entering freshwater river and streams as glass eels or elvers (see eel life history).

An example of a euryhaline species is the bull shark, which lives in Lake Nicaragua of Central America and the Zambezi River of Africa. Both these habitats are fresh water, yet bull sharks will also migrate to and from the ocean. Specifically, Lake Nicaragua bull sharks migrate to the Atlantic Ocean and Zambezi bull sharks migrate to the Indian Ocean.

Diel vertical migration is a common behavior; many marine species move to the surface at night to feed, then return to the depths during daytime.

A number of large marine fishes, such as the tuna, migrate north and south annually, following temperature variations in the ocean. These are of great importance to fisheries.

Freshwater (potamodromous) fish migrations are usually shorter, typically from lake to stream or vice versa, for spawning purposes. However, potamodromous migrations of the endangered Colorado pikeminnow of the Colorado River system can be extensive. Migrations to natal spawning grounds can easily be 100 km, with maximum distances of 300 km reported from radiotagging studies.[13] Colorado pikeminnow migrations also display a high degree of homing and the fish may make upstream or downstream migrations to reach very specific spawning locations in whitewater canyons.[14]

Sometimes the migration of fish is possible when birds eat fish eggs. They carry eggs in digestive tracts and then deposit them in a new place in the form of faeces.[15]

Historic exploitation

Since prehistoric times humans have exploited certain anadromous fishes during their migrations into freshwater streams, when they are more vulnerable to capture. Societies dating to the Millingstone Horizon are known which exploited the anadromous fishery of Morro Creek[16] and other Pacific coast estuaries. In Nevada the Paiute tribe has harvested migrating Lahontan cutthroat trout along the Truckee River since prehistoric times. This fishing practice continues to current times, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has supported research to assure the water quality in the Truckee can support suitable populations of the Lahontan cutthroat trout.

Myxovirus genes

Because salmonids live an anadromous lifestyle, they face bacterial viruses from both freshwater and marine ecosystems. Myxovirus resistance (Mx) proteins are part of a GTP-ase family that aid in antiviral immunity, and previously, rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) have been shown to possess three different Mx genes to aid in bacterial defense in both environments. The number of Mx genes can differ among species of fish, with numbers ranging from 1-9 and some outliers like Gadiformes that have totally lost their Mx genes. A study was performed by Wang et al. (2019)[17] to identify more potential Mx genes that resided in rainbow trout. An additional six Mx genes were identified in that study, now named Mx4-9. They also concluded that the trout Mx genes were “differentially expressed constitutively in tissues” and that this expression is increased during development. The Mx gene family is expressed at high levels in the blood and intestine during development, suggesting they are a key to immune defense for the growing fish. The idea that these genes play an important role in development against bacterial viruses suggests they are critical in the trout’s success in an anadromous lifestyle.

See also

- Animal navigation

- Hydrological transport model

- Semelparity and iteroparity – Classes of possible reproductive strategies

- Ocean Tracking Network

- Pacific Ocean Shelf Tracking Project

- Tagging of Pacific Predators

- The Blue Planet – British nature documentary series

Notes

- Dingle, Hugh and Drake, V. Alistair (2007) "What Is Migration?". BioScience, 57(2):113–121. doi:10.1641/B570206

- Atlantic Salmon Life Cycle Archived January 15, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Connecticut River Coordinator's Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Updated: 13 September 2010.

- Secor, David H; Kerr L A (2009). "Lexicon of life cycle diversity in diadromous and other fishes". Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. (69): 537–556.

- Moyle, P.B. 2004. Fishes: An Introduction to Ichthyology. Pearson Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco, CA.

- Silva, S., Araújo, M. J., Bao, M., Mucientes, G., & Cobo, F. (2014). The haematophagous feeding stage of anadromous populations of sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus: low host selectivity and wide range of habitats. Hydrobiologia, 734(1), 187-199.

- Tyus, H.M. 2012. Ecology and Conservation of Fishes. Taylor and Francis Group, CRC Press, Boca Raton, London, New York.

- Myers, George S. (1949). "Usage of Anadromous, Catadromous and allied terms for migratory fishes". Copeia. 1949: 89–97. doi:10.2307/1438482.

- Vilhjálmsson, H (October 2002). "Capelin (Mallotus villosus) in the Iceland–East Greenland–Jan Mayen ecosystem". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 59 (5): 870–883. doi:10.1006/jmsc.2002.1233.

- Barbaro1 A, Einarsson B, Birnir1 B, Sigurðsson S, Valdimarsson S, Pálsson ÓK, Sveinbjörnsson S and Sigurðsson P (2009) "Modelling and simulations of the migration of pelagic fish" Journal of Marine Science, 66(5):826-838.

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea: Text

- Pacific Fishery Management Council: Background: Highly Migratory Species

- FAO (2007) Report of the FAO workshop on vulnerable ecosystems and destructive fishing in deep sea fisheries Rome, Fisheries Report No. 829.

- Lucas, M.C., and E. Baras. (2001) Migration of freshwater fishes. Blackwell Science Ltd., Malden, MA

- Tyus, H.M. 2012. Ecology and conservation of fishes. Taylor and Francis Group, CRC Press, Boca Raton, London, New York.

- "Experiment shows it is possible for fish to migrate via ingestion by birds". phys.org. Retrieved 2020-06-23.

- C.M. Hogan, 2008

- Wang, T. (2019). "Lineage/species-specific expansion of the Mx gene family in teleosts: Differential expression and modulation of nine Mx genes in rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss". Fish and Shellfish Immunology. 90: 413–430.

References

- Blumm, M (2002) Sacrificing the Salmon: A Legal and Policy History of the Decline of Columbia Basin Salmon Bookworld Publications.

- Bond, C E (1996) Biology of Fishes, 2nd ed. Saunders, pp. 599–605.

- Hogan, C M (2008) Morro Creek, The Megalithic Portal, ed. by A. Burnham

- Lucas, M.C., and E. Baras. (2001) Migration of freshwater fishes. Blackwell Science Ltd., Malden, MA

- Appendix A: Migratory Fish Species in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa in Carolsfield J, Harvey B, Ross C and Anton Baer A (2004)Migratory Fishes of South America World Fisheries Trust/World Bank/IDRC. ISBN 1-55250-114-0.

Further reading

- Ueda H and Tsukamoto K (eds) (2013) Physiology and Ecology of Fish Migration CRC Press. ISBN 9781466595132.

External links

![]()

- United Nations: Introduction to the Convention on Migratory Species

- Living North Sea – International project on tackling fish migration problems in the North Sea Region

- Fish Migration Network – Worldwide network of specialist working on the theme fish migration