Sergei Witte

Count Sergei Yulyevich Witte (Russian: Серге́й Ю́льевич Ви́тте, romanized: Sergéj Júl'jevič Vitte, pronounced [ˈvʲitɨ];[1] 29 June [O.S. 17 June] 1849 – 13 March [O.S. 28 February] 1915), also known as Sergius Witte, was a highly influential politician, and prime minister in Imperial Russia, one of the key figures in the political arena at the end of 19th and at the beginning of the 20th century.[2] He was made a count because of his service to the government in negotiations over the end of the Russo-Japanese War.

Sergei Yulyevich Witte Серге́й Ю́льевич Ви́тте | |

|---|---|

Sergei Witte, early 1880s | |

| 1st Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 6 November 1905 – 5 May 1906 | |

| Monarch | Nicholas II |

| Preceded by | New Post (Himself as Chairman of the Committee of Ministers) |

| Succeeded by | Ivan Goremykin |

| Chairman of the Committee of Ministers | |

| In office 1903–1905 | |

| Monarch | Nicholas II |

| Preceded by | Ivan Nikolayevich Durnovo |

| Succeeded by | Post abolished (Himself as Prime Minister) |

| 13th Finance Minister of Imperial Russia | |

| In office 30 August 1892 – 16 August 1903 | |

| Preceded by | Ivan Vyshnegradsky |

| Succeeded by | Eduard Pleske |

| 14th Transport Minister of Imperial Russia | |

| In office February 1892 – August 1892 | |

| Preceded by | Adolf Gibbenet |

| Succeeded by | Apollon Krivoshein |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Sergei Yulyevich Witte 29 June 1849 Tiflis, Caucasus Viceroyalty, Russian Empire (now Tbilisi, Georgia) |

| Died | 13 March 1915 (aged 65) Petrograd, Russian Empire |

| Cause of death | Brain tumor |

| Resting place | Alexander Nevsky Monastery, Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater | Novorossiysk University |

| Signature | |

Witte was neither a liberal nor a conservative. He attracted foreign capital to boost Russia's industrialization. He served under the last two emperors of Russia, Alexander III and Nicholas II.[3] During the Russo-Turkish War (1877–78), he had risen to a position in which he controlled all the traffic passing to the front along the lines of the Odessa Railways. As Minister of Finance, Witte presided over extensive industrialization and achieved monopoly control by the government over an expanded system of railroad lines.

Following months of civil unrest and outbreaks of violence, in what was known as the 1905 Russian Revolution, he framed the October Manifesto of 1905, and the accompanying government communication to establish constitutional government. He was not convinced it would solve Russia's problems with the Tsarist autocracy. On 20 October 1905 Witte was appointed as the first Chairman of the Russian Council of Ministers (effectively Prime Minister). Assisted by his Council, he designed Russia's first constitution. But within a few months, Witte fell into disgrace as a reformer because of continuing court opposition to these changes. He resigned before the First Duma assembled. Witte was fully confident that he had resolved the main problem: providing political stability to the regime,[2] but according to him, the "peasant problem" would further determine the character of the Duma's activity.[4]

Witte has been described by Figes as the 'great reforming finance minister of the 1890s',[5] 'one of Nicholas's most enlightened ministers',[6] and the architect of Russia's new parliamentary order in 1905.[7]

Family and early life

Witte's father Julius Chistoph Heinrich Georg Witte was from a Lutheran Baltic German family of Dutch origin.[8] He converted to Russian Orthodoxy upon marriage with Yekaterina Fadeyeva. His father was made a member of the knighthood in Pskov, the second-largest city in the Russian Empire, but moved as a civil servant to Saratov and Tiflis (present-day Tbilisi, Georgia). Sergei was raised on the estate of his mother's parents.[2] His grandfather was Andrei Mikhailovich Fadeyev, a Governor of Saratov and Privy Councillor of the Caucasus, his grandmother was Princess Helene Dolgoruki. Sergei had two brothers (Alexander and Boris) and two sisters (Olga and Sophia).[9][10] Helena Blavatsky, noted as a mystic, was their first cousin. Witte studied at a Tiflis gymnasium, but he took more interest in music, fencing and riding than in academics. He finished Gymnasium I in Kishinev[11] and began studying Physico-Mathematical Sciences at the Novorossiysk University in Odessa in 1866, graduating top of his class in 1870.[12]

Witte had initially planned to pursue a career in academia, intending to become a professor in Theoretical Mathematics. His relatives took a dim view of this career path as it was considered unsuitable for a noble or aristocrat at the time. He was instead persuaded by Count Vladimir Alekseyevich Bobrinsk, then Minister of Ways and Communication, to pursue a career in the railroads. At the direction of the Count, Witte undertook six months of training in a variety of positions on the Odessa Railways in order to gain a practical understanding of Ukrainian railways operations. At the end of this period, he was appointed as chief of the traffic office.[13]

After a wreck on the Odessa Railways in late 1875 cost many lives, Witte was arrested and sentenced to four months in prison. However, while still contesting the case in court, Witte directed the Odessa Railways in achieving extraordinary efforts towards the transport of troops and war materials in the Russo-Turkish War, and attracted the attention of Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, who commuted his prison sentence to two weeks. Witte had devised a novel system of double-shift operations in his efforts to overcome delays on the rail lines.[14]

In 1879, Witte accepted a post in St. Petersburg, where he would meet his future wife. He moved to Kiev the following year. In 1883, he published a paper on "Principles of Railway Tariffs for Cargo Transportation", in which he also discussed social issues and the role of the monarchy. Witte gained popularity in the government. In 1886, he was appointed manager of the privately held Southwestern Railways, based in Kiev, and was noted for increasing its efficiency and profitability. Around this time, he met Tsar Alexander III. But he had conflict with the Tsar's aides when he warned of the danger in their practice of using two powerful freight locomotives to achieve high speeds for the Royal Train. His warnings were proven in the October 1888 Borki train disaster; afterward, Witte was appointed as Director of State Railways.

Political career

._1905._Karl_Bulla.jpg)

Railways

Witte worked in railroad management for twenty years, after having begun as a ticket clerk.[5] He served as Russian Director of Railway Affairs within the Finance Ministry from 1889 to 1891; and during this period, he oversaw an ambitious program of railway construction. Until then less than one-fourth of the small railway systems was under direct state control, but Witte set about expanding the rail lines and getting the railway service under control as a State monopoly. Witte also obtained the right to assign employees based on their performance, or merit, rather than for patronage, that is, political or familial connections. In 1889, he published a paper titled "National Savings and Friedrich List", which cited the economic theories of Friedrich List and justified the need for a strong domestic industry, protected from foreign competition by customs barriers.

A new customs law for Russia was passed in 1891, spurring an increase in industrialization by the turn of the 20th century. At the same time that Witte worked to achieve industrialization, he also fought for practical education. He said that railways operated by the state would be useless "unless it does its utmost for spreading technical education..."[15]

Tsar Alexander III appointed Witte in 1892 as acting Minister of Ways and Communications.[12] This gave him both control of the railroads in Russia and the authority to impose a reform on the tariffs charged. "Russian railroads gradually became perhaps the most economically operated railroads of the world.".[16] Profits were high: over 100 million gold rubles a year to the government (exact amount unknown due to accounting defects).

In 1892 Witte became acquainted with Matilda Ivanovna (Isaakovna) Lisanevich in a theater.[9] Witte began to seek her favour, urging her to divorce her gambling husband and marry him. The marriage was a scandal, not only because Matilda was a divorcee, but also because she was a converted Jew. It cost Witte many of his connections with the upper nobility, but the Tsar protected him.

Minister of Finance

In August 1892, Witte was appointed to the post of Minister of Finance, a post which he held for the next eleven years. (Until 1905 matters pertaining to industry and commerce were within the province of the Ministry of Finance.) During his tenure, he greatly accelerated the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway. He also emphasized creation of an educational system to train personnel for industry, in particular, the establishment of new "commercial" schools. He was known for appointing subordinates by their academic credentials or merit, rather than because of patronage political connections. In 1894, he concluded a 10-year commercial treaty with the German Empire on favorable terms for Russia. When Alexander III died, he told his son on his deathbed to listen well to Witte, his most capable minister.

In 1895, Witte established a state monopoly on alcohol, which became a major source of revenue for the Russian government. In 1896, he concluded the Li–Lobanov Treaty with Li Hongzhang of the Qing dynasty. One of the rights secured for Russia was the construction of the Chinese Eastern Railway across northeast China, which greatly shortened the route of the Trans-Siberian Railway to its projected eastern terminus at Vladivostok. However, following the Triple Intervention, Witte strongly opposed the Russian occupation of Liaodong Peninsula and the construction of the naval base at Port Arthur in the Russia–Qing Convention of 1898.

Gold standard

In 1896, Witte undertook a major currency reform to place the Russian ruble on the gold standard. This resulted in increased investment activity and an increase in the inflow of foreign capital. Witte also enacted a law in 1897 limiting working hours in enterprises, and in 1898 reformed commercial and industrial taxes.[17]

In summer 1898 he addressed a memorandum to the Tsar[18] calling for an agricultural conference on the reform of the peasant community. This resulted in three years of talks about laws to abolish collective responsibility and facilitate the resettlement of farmers onto lands on the outskirts of the Empire. Many of his ideas were later adopted by Pyotr Stolypin. In 1902 Witte's supporter, Dmitry Sipyagin, the Minister of Home Affairs, was assassinated. In an attempt to keep up the modernization of the Russian economy, Witte called and oversaw the Special Conference on the Needs of the Rural Industry. This conference was to provide recommendations for future reforms and compile the data to justify those reforms. By 1900 the growth in the manufacturing industry had been four times faster than in the preceding five-year period and six times faster than in the decade before that. External trade in industrial goods was equal to that of Belgium.[19] In 1904 the Union of Liberation was formed, which demanded economic and political reform.

Worsening relations with Japan in 1890s

Witte controlled East Asian policy in the 1890s. His goal was peaceful expansion of trade with Japan and China. Japan, with its greatly expanded and modernized military, easily defeated the antiquated Chinese forces in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95). Russia had to confront collaborating with Japan (with which relations had been fairly good for some years) or acting as protector of China against Japan. Witte chose the second policy and, in 1894, Russia joined Britain and France in forcing Japan to soften the peace terms it imposed on China. Japan was forced to cede the Liaodong Peninsula and Port Arthur back to China (both territories were located in south-eastern Manchuria, a Chinese province).

This new Russian role angered Tokyo, which decided Russia was the main enemy in its quest to control Manchuria, Korea, and China. Witte underestimated Japan's growing economic and military power while exaggerating Russia's military prowess. Russia concluded an alliance with China (in 1896 by the Li–Lobanov Treaty), which led in 1898 to Russian occupation and administration (by its own personnel and police) of the entire Liaodong Peninsula. Russia also fortified the ice-free Port Arthur, and completed the Russian-owned Chinese Eastern Railway, which was to cross northern Manchuria from west to east, linking Siberia with Vladivostok. In 1899 the Boxer Rebellion broke out, and the Chinese attacked all foreigners. A large coalition of the major Western powers and Japan sent armed forces to relieve their diplomatic missions in Peking. The Russian government used this as an opportunity to bring a substantial army into Manchuria. As a consequence, by 1900 Manchuria was a fully incorporated outpost of the Russian Empire, and Japan prepared to fight Russia.[20]

Loss of power

Witte, in a memorandum, tried to turn the reports of the zemstvo presidents into a condemnation of the Home Office.[21] In a political conflict on land reform, Vyacheslav von Plehve accused him of being part of a Jewish-Masonic conspiracy.[22] According to Vasily Gurko, Witte had dominated the irresolute Tsar, and his opponents decided this was the moment to get rid of him.

Witte was appointed on 16 August 1903 (O.S.) as chairman of the Committee of Ministers, a position he held until October 1905.[12] While officially a promotion, the post had no real power. Witte's removal from the influential post of Minister of Finance was engineered under the pressure of the landed gentry and his political enemies within the government and at the court. But historians Nicholas V. Riasanovsky and Robert K. Massie say that Witte's opposition to Russian designs on Korea resulted in his resigning from the government in 1903.[23][24]

Diplomatic career

Witte was brought back into the governmental decision-making process to help deal with growing civil unrest. Confronted with increasing opposition and, after consulting with Witte and Prince Sviatopolk-Mirsky, the Tsar issued a reform ukase on December 25, 1904 with vague promises.[25] After the Bloody Sunday riots of 1905, Witte supplied 500 rubles, the equivalent of 250 dollars, to Father Gapon in order for the leader of the demonstration to leave the country.[26] Witte recommended that the government issue a manifesto related to the people's demands.[27] Schemes of reform would be elaborated by Goremykin and a committee consisting of elected representatives of the zemstva and municipal councils under the presidency of Witte. On 3 March the Tsar condemned the revolutionaries. The government issued a strongly worded prohibition of any further agitation in favor of a constitution.[28] By spring a new political system was beginning to form in Russia. A petition campaign was conducted seeking a wide variety of proposed changes, such as ending the war with Japan, which lasted from February to July 1905. In June mutiny broke out on the Russian battleship Potemkin.

The Tsar called upon Witte to negotiate an end to the Russo-Japanese War.[12] He was sent to the United States for the talks, as the Russian Emperor's plenipotentiary titled "his Secretary of State and President of the Committee of Ministers of the Emperor of Russia," along with Baron Roman Rosen, Master of the Imperial Court of Russia.[29] The peace talks were held in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Witte is credited with negotiating brilliantly on Russia's behalf during these Treaty of Portsmouth discussions. Russia lost little in the final settlement.[12] For his efforts, Witte was created a Count.[9][30] But the loss of the war with Japan is believed to have marked the beginning of the end of Imperial Russia.

After this diplomatic success, Witte wrote to the Tsar stressing the urgent need for political reforms at home. He was dissatisfied with proposals by Bulygin, the successor of Sviatopolk-Mirsky. A 6 August (O.S.) manifesto created a Duma as a consultative body only. Elections of its representatives would not be direct but would be held in four stages, and qualifications for class and property would exclude much of the intelligentsia and all of the working classes from suffrage. The proposal was greeted by numerous protests and strikes across the country, which became known as the Russian Revolution of 1905.

During this period, imperial troops were sent out 2,000 times to suppress violence. The Tsar remained quiet, impassive and indulgent; he spent most of that autumn hunting.[31] Witte told Nicholas II, "that the country was at the verge of a cataclysmic revolution". Trepov was ordered to take drastic measures to stop the revolutionary activity. The Tsar asked his cousin Grand Duke Nicholas to assume the role of dictator, but the Grand Duke threatened to shoot himself if the Tsar refused to endorse Witte's memorandum.[32] Nicholas II had no choice but to take a number of steps in the constitutional liberal direction.[9] The Tsar accepted the draft, hurriedly outlined by Aleksei D. Obolensky.[33][34] It was known as the October Manifesto. This promised to grant civil liberties such as freedom of conscience, speech, and association; constitutional order, representative government, and the establishment of an Imperial Duma.[14] As the Duma was only a consultative body, the Council of Ministers or the Tsar still had the right to block certain proposals. Many Russians felt that this reform did not go far enough;[22] and it did not achieve universal suffrage for men.

Chairman of the Council of Ministers

Witte described the regime's usual "incompetence and obstinacy" in response to the crisis of 1904–1905 as a "mixture of cowardice, blindness and stupidity".[35]

On 8 January 1905, Witte and Sviatopolk-Mirsky had been approached by a delegation of intellectuals led by Maxim Gorky, who begged them to negotiate with demonstrators. After the government's postings of warnings of 'resolute measures' against street gatherings led by Father Gapon, they worried about violent confrontation, which did take place. They were unsuccessful as the government had believed they could control Fr. Gapon.[36] Leaving has visiting cards with Witte and Mirsky, Gorky was arrested, along with the other members of the deputations.[37]

In later 1905 Witte was approached by the Tsar's advisers, in an effort to save the country from complete collapse, and on 9 October 1905, he went to the Winter Palace for a meeting. Here he told the Tsar 'with brutal frankness' that the country was on the verge of a catastrophic revolution, which he said 'would sweep away a thousand years of history'. He presented the Tsar with two choices: either appoint a military dictator, or agree to broad and major reforms. In a memorandum arguing for a manifesto, Witte outlined the reforms needed to appease the masses.

He argued for the following reforms: creation of a legislative parliament (Imperial Duma) elected via a democratic franchise; granting of civil liberties; establishing a cabinet government and a 'constitutional order'.[31] These demands, which basically comprised the political programme of the Liberation Movement, were an attempt to isolate the political Left by pacifying the liberals.[31] Witte emphasised that repression would be only a temporary solution to the problem, and a risky one, because he believed the armed forces — whose loyalty was now in question — could collapse if they were to be used against the masses.[31] Most of the military advisers to the Tsar agreed with Witte, as did the Governor of St. Petersburg, Alexander Trepov, who wielded considerable influence at court. Only when Nicholas II's uncle Grand Duke Nikolai threatened to shoot himself if he did not agree to Witte's demands, following the Tsar's request for him to accept appointment as dictator, did the Tsar agree. He was embarrassed to have been forced by a former 'railway clerk', a man who was a bureaucrat and 'businessman,' to relinquish his autocratic rule.[31][nb 1] Witte later said that the Tsar's court were ready to use the Manifesto as a temporary concession, and later return to autocracy' when the revolutionary tide subsided'.[38]

In October Witte was charged with the task of assembling the nation's first cabinet government, and he offered the liberals several portfolios: Ministry of Agriculture to Ivan Shipov; Ministry of Trade and Industry to Alexander Guchkov; Ministry of Justice to Anatoly Koni and the Ministry of Education to Evgenii Troubetzkoy. Pavel Milyukov and Prince Georgy Lvov were also offered ministerial posts. None of these liberals agreed to join the government, though. Witte had to form his cabinet from 'tsarist bureaucrats and appointees lacking public confidence'. The Kadets doubted that Witte could deliver on the promises made by the Tsar in October, knowing the Tsar's staunch opposition to reform.[39]

Witte argued that the Tsarist regime could be saved from a revolution only by the transformation of Russia to a 'modern industrial society', in which 'personal and public initiatives' were encouraged by a rechtsstaat who guaranteed civil liberties.[5]

In the two weeks following the October Manifesto, several pogroms took place against Jews, especially in St. Petersburg and Odessa. Witte ordered an official investigation, where it was revealed that the police in the former city had organised, armed and gave vodka to the anti-semitic crowds, and even participated in the attacks. Witte demanded the prosecution of the chief of police in St. Petersburg], who was involved in the printing of anti-semitic pamphlets, but the Tsar intervened and protected him.[40] Witte believed that anti-semitism was 'considered fashionable' among the elite.[41] In the aftermath of the Kishinev pogrom in 1903, Witte had said that if Jews 'comprise about fifty percent of the membership in the revolutionary parties', it was 'the fault of our government. The Jews are too oppressed'.[42]

Milyukov once confronted Witte, asking why he would not commit himself to a constitution; Witte replied that he couldn't 'because the Tsar does not wish it'.[43] Witte was worried that the court were only using him, which emerged in talks with members of the Kadet Party.[43]

After his skillful diplomacy Witte was appointed as Chairman of the Council of Ministers, the equivalent of Prime Minister, and formed Sergei Witte's Cabinet, not belonging to any party, as there were none. No longer was the Tsar the head of the government. "Immediately upon my nomination as President of the Imperial Council I made it clear that the Procurator of the Most Holy Synod Konstantin Pobedonostsev, could not remain in office, for he definitely represented the past."[44] He was replaced by Prince Alexey D. Obolensky. Trepov and Bulygin were dismissed and, after many discussions, Durnovo was appointed as Minister of Interior on 1 January 1906; his appointment is considered one of the greatest errors Witte made during his administration.

According to Harold Williams: "That government was almost paralyzed from the beginning. Witte acted immediately by urging the release of political prisoners and the lifting of censorship laws."[45] Alexander Guchkov and Dmitry Shipov refused to work with the reactionary Durnovo and to support the government. On 26 October (O.S.) the Tsar appointed Trepov as Master of the Palace without consulting Witte, and had daily contact with the Emperor; his influence at court was paramount. "In addition mass violence broke out in the days following the issuance of the October Manifesto. The major source of the unrest was unrelated to the October Manifesto. It took the form of attacks by gangs in the cities on the Jews. In general, the authorities ignored the attacks.[45]

On 8 November the sailors in Kronstadt mutinied. In the same month the border provinces were clearly taking advantage of the weakening of Central Russia to show their teeth. Witte later wrote in his Memoirs about the empire's ethnic minorities:

The dominating element of the Empire, the Russians, fall into three distinct ethnic branches: the Great, the Little, and the White Russians, and 35 per cent, of the population is non-Russian. It is impossible to rule such a country and ignore the national aspirations of its varied non-Russian national groups, which largely make up the population of the Great Empire. The policy of converting all Russian subjects into "true Russians" is not the ideal which will weld all the heterogeneous elements of the Empire into one body politic. It might be better for us Russians, I concede, if Russia were a nationally uniform country and not a heterogeneous Empire. To achieve that goal there is but one way, namely to give up our border provinces, for these will never put up with the policy of ruthless Russification. But that measure our ruler will, of course, never consider.[46]

On 10 November Russian Poland was placed under martial law.

Witte's position was not well established. The Liberals remained obdurate and refused to be cajoled. The Peasants' Union asked the Russian people to refuse to make redemption payments to the government and withdraw their deposits from banks that might be subject to government action.[47] He promised an eight-hour working day and tried to secure vital loans from France to keep the "regime" from bankruptcy.[14]

Witte sent his envoy to the Rothschild bank; they responded that

"they would willingly render full assistance to the loan, but that they would not be in a position to do so until the Russian Government had enacted legal measures tending to improve the conditions of the Jews in Russia. As I deemed it beneath our dignity to connect the solution of our Jewish question with the loan, I decided to give up my intention of securing the participation of the Rothschilds."[48]

On 24 November by Imperial decree provisional regulations on the censorship of magazines and newspaper was released.[49]

On 16 December Trotsky and the rest of the executive committee of the St. Petersburg Soviet were arrested.[22] The Minister of Agriculture Nikolai Kutler resigned in February 1906; Witte refused to appoint Alexander Krivoshein. In the next few weeks, changes and additions to the Russian Constitution of 1906 were made, so that the Emperor was confirmed as the dictator of foreign policies and the supreme commander of the army and navy. The ministers remained responsible solely to Nicholas II, not to the Duma. The "peasant question" or land reforms was a hot issue; the influence of the "Duma of Public Anger" had to be limited, according to Goremykin and Dmitri Trepov. The Bolsheviks boycotted the coming election. When Witte discovered that Nicholas never intended to honour these concessions, he resigned as Chairman of the Council of Ministers. The position and influence of General Trepov, Grand Duke Nicholas, the Black Hundreds, and overwhelming victories by the Kadets in the 1906 Russian legislative election, forced Witte on 14th to resign, which was announced 22 April 1906 (O.S.).

Witte confessed to Polovtsov in April 1906 that the success of the repressions in the wake of the Moscow uprising in 1905 had resulted in his losing all influence over the Tsar. Despite Witte's protests, Durnovo was allowed to 'carry out a brutal and excessive, and often totally unjustified, series of repressive measures.'[50]

In 1906 Father Gapon returned to Russia from exile and supported Witte's government.[51] On 30 April 1905 Witte proposed the Law of Religious Toleration, followed by the edict of 30 October 1906 giving legal status to schismatics and sectarians of the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC), the established state church.[52] Witte argued that ending discrimination against religious rivals of the Orthodox Church 'would not harm the church, provided it embraced the reforms that would revive its religious life'. Although the Church's 'senior hierarchs' may for some time have played with the thought of self-government, Witte's demand that this would come at the cost of religious toleration 'guaranteed to drive them back into the arms of reaction'.[53] Witte had made this demand (self-government in exchange for religious toleration) in the hope of 'wooing' the important commercial groups of the ethnic minorities of Jewish and Old-Believer communities.[53]

Member of the State Council

Witte continued in Russian politics as a member of the State Council but he was never again appointed to an administrative role in the government. He was ostracized by the Russian establishment. In January 1907 a bomb was found planted in his home. The investigator Pavel Alexandrovich Alexandrov proved that the Okhrana, the tsarist secret police, had been involved.[54][55] During the winter season, Witte lived in Biarritz and started writing his Memoirs,[56] but he returned to St Petersburg in 1908.

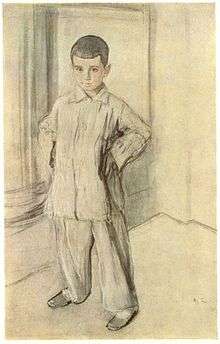

During the July Crisis in 1914, Grigori Rasputin and Witte desperately urged the Tsar to avoid the conflict and warned that Europe faced calamity if Russia became involved. The advice went unheeded; the French ambassador Maurice Paléologue complained to the Minister of Foreign Affairs Sazonov. Witte died shortly afterwards at his home in St. Petersburg; his death was attributed to meningitis or a brain tumor. His third-class funeral was held at the Alexander Nevsky Lavra. Witte had no children, but he had adopted his wife's by her first marriage. According to Edvard Radzinsky, Witte asked for the title of count to be given to his grandson L.K. Naryshkin (b. 1905, see image above). Nothing is known about his life after this period.

Witte's reputation was burnished in the West after his secret memoirs were published in translation in 1921. They had been completed in 1912 and kept in a bank in Bayonne, France. He had left orders that they could not be published during the lifetimes of him and his contemporaries. The original manuscript of his memoirs are now held in Columbia University Library's Bakhmeteff Archive of Russian and East European History and Culture.[3]

Honors

.png)

- Order of Vasa (Sweden), Grand Cross, 1897

- Order of the Crown (Prussia)

- The Sergei Witte University of Moscow, with campuses in Ryazan, Krasnodar and Nizhny Novgorod is named in his honour (a private institution accredited by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Russia) in 1997)

Popular culture depictions

- Witte was portrayed by Laurence Olivier in the film Nicholas and Alexandra (1971).

- He was portrayed by Freddie Jones in the British BBC series Fall of Eagles (1974).

See also

- History of the Russian Far East

- History of Sino-Russian relations

Footnotes

- Not even his abdication in 1917 was considered as big a humiliation than agreeing to the demands.[38]

References

- F.L. Ageenko and M.V. Zarva, Slovar' udarenii (Moscow: Russkii yazyk, 1984), p. 547.

- "Sergei Witte – Russiapedia Politics and society Prominent Russians". russiapedia.rt.com.

- Harcave, Sidney. (2004). Count Sergei Witte and the Twilight of Imperial Russia: A Biography, p. xiii.

- Witte's Memoirs, p. 359

- Figes, p. 41

- Figes, p. 8

- Figes, p. 217

- His ancestors lived in Friedrichstadt in the Courland Governorate and not in Holstein.

- "История России в портретах. В 2-х тт. Т.1. с.285-308 Сергей Витте". www.peoples.ru.

- "Sergei Yulyevich Count Witte". geni_family_tree.

- (in Russian) Kto-is-kto.ru Archived 2009-07-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Harcave, p. 33.

- Harcave, p. 42.

- "Sergey Yulyevich, Count Witte - prime minister of Russia".

- Peter Kropotkin (1901). "The Present Crisis in Russia". The North American Review.

- Boublikoff, p. 313

- B. V. Ananich & R. S. Ganelin (1996) "Nicholas II," p. 378. In: D. J. Raleigh: The Emperors and Empresses of Russia. Rediscovering the Romanovs. The New Russian History Series.

- Witte's Memoirs, pp. 211–215

- "Witte on economic tasks". pages.uoregon.edu.

- B. V. Ananich, and S. A. Lebedev, "Sergei Witte and the Russo-Japanese War." International Journal of Korean History 7.1 (2005): 109-131. Online

- Ward, Sir Adolphus William (7 August 2018). "The Cambridge Modern History". CUP Archive – via Google Books.

- "Sergei Witte".

- Riasanovsky, N. V. (1977) A History of Russia, p. 446

- Massie, Robert K. (1967). Nicholas and Alexandra (1st Ballantine ed.). Ballantine Books. p. 90. ISBN 0-345-43831-0.

- Harold Williams, Shadow of Democracy, p. 11, 22

- Witte, Sergei IUl'evich; Yarmolinsky, Avrahm (7 August 2018). "The memoirs of Count Witte". Garden City, N.Y. Doubleday, Page – via Internet Archive.

- Williams, p. 77

- Williams, p. 22-23

- "Text of Treaty; Signed by the Emperor of Japan and Czar of Russia," New York Times. October 17, 1905.

- Massie, Nicholas and Alexandra P.97

- Figes, p. 191

- Scenarios of Power, From Alexander II to the Abdication of Nicholas II, by Richard Wortman, pg. 398

- V.I.Gurko (7 August 2018). "Features And Figures Of The Past Government And Opinion In The Reign Of Nicholas II". Russell & Russell – via Internet Archive.

- Witte's Memoirs, p. 241

- Figes, p. 186

- Figes, p. 175

- Figes, p. 179

- Figes, p. 192

- Figes, p. 194–5

- Figes, p. 197

- Figes, p. 242

- Figes, p. 82

- Figes, p. 195

- Witte's Memoirs

- Williams, p. 166

- Witte's Memoirs, p. 265

- Williams, p. 220

- Witte's Memoirs, p. 293-294

- "1905 :: Электронное периодическое издание Открытый текст". www.opentextnn.ru.

- Figes, p. 201

- Figes, p. 178n

- Pospielovsky, Dmitry (1984). The Russian Church Under the Soviet Regime. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir Seminary Press. p. 22. ISBN 0-88141-015-2.

- Figes, p. 69

- «ПОКУШЕНИЕ НА МОЮ ЖИЗНЬ», «Воспоминания» С. Ю. Витте, т. II-ой, 1922 г. Книгоиздат. «Слово» (in Russian)

- Покушение на графа Витте (2011-10-15), сканер копии — Юрий Штенгель (in Russian)

- Design, Pallasart Web. "Count Sergei Iulevich Witte - Blog & Alexander Palace Time Machine". www.alexanderpalace.org.

Bibliography

- Ananich, B. V. and S. A. Lebedev, "Sergei Witte and the Russo-Japanese War." International Journal of Korean History 7.1 (2005): 109-131. Online

- Boublikoff, A.A. "A suggestion for railroad reform". In: Buehler, E.C. (editor) "Government ownership of railroads", Annual Debater's Help Book (vol. VI), New York, Noble and Noble, 1939; pp. 309–318. Original in journal North American Review, vol. 237, pp. 346+. (This issue is 90% about Russian railways.)

- Davis, Richard Harding, and Alfred Thayer Mahan. (1905). The Russo-Japanese war; a photographic and descriptive review of the great conflict in the Far East, gathered from the reports, records, cable despatches, photographs, etc., etc., of Collier's war correspondents New York: P. F. Collier & Son. OCLC: 21581015

- Figes, Orlando (2014). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891–1924. London: The Bodley Head. ISBN 9781847922915.

- Harcave, Sidney. (2004). Count Sergei Witte and the Twilight of Imperial Russia: A Biography. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1422-3 (cloth)

- Kokovtsov, Vladamir. (1935). Out of My Past (translator, Laura Matveev). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Korostovetz, J.J. (1920). Pre-War Diplomacy The Russo-Japanese Problem. London: British Periodicals Limited.

- Theodore H. von Laue (1963) Sergei Witte and the Industrialization of Russia

- Witte, Sergei. (1921). The Memoirs of Count Witte (translator, Abraham Yarmolinsky). New York: Doubleday. online free

- Wcislo, Francis W. (2011). Tales of Imperial Russia: The Life and Times of Sergei Witte, 1849-1915. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954356-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sergei Witte. |

- Portsmouth Peace Treaty, 1905-2005

- Memoirs of Count Witte, 1921 English translation, available in full online at Internet Archive

- The Museum Meiji Mura—peace treaty table on display

- Newspaper clippings about Sergei Witte in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Adolf Gibbenet |

Transport Minister February 1892 – August 1892 |

Succeeded by Apollon Krivoshein |

| Preceded by Ivan Vyshnegradsky |

Finance Minister 1892–1903 |

Succeeded by Eduard Pleske |

| Preceded by Ivan Durnovo |

Chairman of the Committee of Ministers 1903–1905 |

Succeeded by Himself as Prime Minister |

| Preceded by Himself as Chairman of the Committee of Ministers |

Prime Minister of Russia 2 November 1905 – 5 May 1906 |

Succeeded by Ivan Goremykin |