Lusterware

Lusterware or Lustreware (respectively the US and all other English spellings) is a type of pottery or porcelain with a metallic glaze that gives the effect of iridescence. It is produced by metallic oxides in an overglaze finish, which is given a second firing at a lower temperature in a "muffle kiln", or a reduction kiln, excluding oxygen. The discovery of this technique can be traced back to the 7th century A.D. when Islam emerged in the city of Mecca.[1]

.jpg)

The technique of lusterware on ceramic was developed originally in Samarra, Iraq. Lusterware traveled along the trade routes; the production of ceramic lusterware was seen in Egypt and Syria during later centuries. Lusterware was produced in quantity in Egypt during the Fatimid dynasty in the 10th–12th centuries. While the production of lusterware continued in the Middle East and Persia, it spread to Europe through Al-Andalus. Málaga was the first centre of Hispano-Moresque ware, before it developed in the region of Valencia, and then to Italy, where it was used to enhance maiolica. In the 16th century lustred maiolica was a specialty of Gubbio, noted for a rich ruby red, and at Deruta.[2] There was a revival in England and other European countries in the late 18th-century, continuing into the 19th.

Pre-modern wares

Early Islamic lusterware ceramics were predominately produced in lower Iraq during the ninth and tenth centuries.[3] In the Great Mosque of Kairouan, Tunisia, the upper part of the mihrabis adorned with polychrome and monochrome lusterware tiles; dating from 862 to 863, these tiles were most probably imported from Mesopotamia. The reminiscence of shining metal, especially gold, made lustreware especially attractive. Lusterware is extremely decorative so there is no exception when it comes to ceramics. The bowls were painted with ornamental patterns and designs. Some were lusterware pieces used for religious purposes while others were acceptable for daily use. Some pieces were signed by their makers, this acted as an indication of the admiration towards each craftsman. Trading in the Middle East was very popular. Abbasid lusterware was very common in trade within the Islamic world. The city of Baghdad, Iran and surrounding cities were located on the Silk Road which was the hub of trading during this period. There was a movement of goods generated between Iraq and China which triggered artistic emulations both ends, as well as some transfers of technologies, notably in the realm of ceramics.[4]

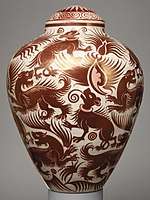

After a gap of several centuries in Persian production, it was revived in the Safavid period from about the 1630s, in a rather different style, typically producing small pieces with designs often in a dark copper colour over a dark blue (cobalt) background. Unlike other Persian wares of the period, these use traditional Middle Eastern shapes and decoration rather than Chinese-inspired ones, and also do not take their shapes from metalware. Designs featured plant forms and animals, and generally flowed freely over the whole surface, typically taking up over half the surface area. Production, which was never large, appears to have mostly been from about 1650 to 1750, but with rather inferior wares produced into the 19th century. It is often thought to have been centred in Kirman, though firm evidence is lacking.[5]

11th century bowl fragment, with mounted rider, Egypt, Fatimid dynasty

11th century bowl fragment, with mounted rider, Egypt, Fatimid dynasty- Bowl, Kashan, Iran, c. 1260-1280

.jpg) Bowl, Raqqa, Syria, around 1200

Bowl, Raqqa, Syria, around 1200- Star tile, Kashan, Iran, 13th-14th century

- Hispano-Moresque dish, Manises, 1400-60

- Hispano-Moresque bowl, Andalusia, 1500-1550

Safavid wine jug, Iran, 2nd half 17th century, probably originally with a set of matching cups

Safavid wine jug, Iran, 2nd half 17th century, probably originally with a set of matching cups

Process

In the classical process to make lusterware, a preparation of metal salts of copper or silver, mixed with vinegar, ochre, and clay is applied on the surface of previously-glazed pottery object.[6] The pot is then fired again in a kiln with a reducing atmosphere, at about 600 °C. The salts are reduced to metals and coalesce into nanoparticles. Those partiles give the second glaze a metallic appearance.[7]<[8][9]

Decoration

Some Abbasid lusterware can be differentiated by figural vs. vegetal design where some include icons and others show plant life.[10]Of course, though, some displayed both plants and figures. At this point in time, there was an aesthetic preference for completely covering the surface of objects with ornamental decoration, and this is also the case for lusterware ceramics. As lusterware made appearances in other cultures and countries, less decoration was introduced. Abbasid lusterware can either be polychromeor monochromewhen it comes to the colors featured in the ceramics. It is argued that the different color types share the quality of the surfaces changing under different conditions. The Abbasid people would normally decorate polychrome bowls with vegetal and geometric patterns, while the monochrome bowls usually had large, centrally placed figures.[10]They are visually sensitive and their appearance can change dramatically in particular conditions.[10]The earliest forms of lusterware were decorated with three to four colors, but as time went on the colors used was reduced to two.[11]Recent studies have argued that the preference between polychrome and monochrome has to do with the price of materials and or the availability.[10]This leads to more monochrome wares being produced over polychrome. The Islamic people took great pride in the lusterware and how they were perceived by many; the lustrous sheen that these pieces give off is delightful to the eye and has been adorned by many for centuries. The diversity between the designs of lusterware is endless and the variety plus technique is what makes these wares so desirable. Islamic ceramic production has been thrown on a course of evolution that has been brought into the modern era.[12]

Modern lustreware

Metallic lustre of another sort produced English lustreware, which imparts to a piece of pottery the appearance of an object of silver, gold or copper. Silver lustre employed the new metal platinum, whose chemical properties were analyzed towards the end of the 18th century, John Hancock of Hanley invented the application of a platinum technique, and "put it in practice at Mr Spode's manufactory, for Messrs. Daniels and Brown",[13] about 1800. Very dilute amounts of powdered gold or platinum were dissolved in aqua regia[14] and added to spirits of tar for platinum and a mixture of turpentine, flowers of sulfur and linseed oil for gold. The mixture was applied to the glazed ware and fired in an enameling kiln, depositing a thin film of platinum or gold.[15]

Platinum produced the appearance of solid silver, and was employed for the middle class in shapes identical to those uses for silver tea services, ca. 1810-1840. Depending on the concentration of gold in the lustring compound and the under slip on which it was applied, a range of colours could be achieved, from pale rose and lavender, to copper and gold. The gold lustre could be painted or stenciled on the ware, or it could be applied in the resist technique, in which the background was solidly lustred, and the design remained in the body color. In the resist technique, similar to batik, the design was painted in glue and size in a glycerin or honey compound, the lustre applied by dipping, and the resist washed off before the piece was fired.

Lustreware became popular in Staffordshire pottery during the 19th century, where it was also used by Josiah Wedgwood, who introduced pink and white lustreware simulating mother o' pearl effects in dishes and bowls cast in the shapes of shells, and silver lustre, introduced at Wedgwood in 1805. In 1810 Peter Warburton of New Hall patented a method of transfer-printing in gold and silver lustre. Sunderland Lustreware in the North East is renowned for its mottled pink lustreware, and lustreware was also produced in Leeds, Yorkshire, where the technique may have been introduced by Thomas Lakin.[16]

Wedgwood's lusterware made in the 1820s spawned the production of mass quantities of copper and silver lustreware[17] in England and Wales. Cream pitchers with appliqué-detailed spouts and meticulously applied handles were most common, and often featured stylized decorative bands in dark blue, cream yellow, pink, and, most rare, dark green and purple. Raised, multicolored patterns depicting pastoral scenes were also created, and sand was sometimes incorporated into the glaze to add texture. Pitchers were produced in a range of sizes from cream pitchers to large milk pitchers, as well as small coffeepots and teapots. Tea sets came a bit later, usually featuring creamers, sugar bowls, and slop bowls.

Large pitchers with transfer printed commemorative scenes appear to have arrived around the middle of the 19th century. These were purely decorative and today command high prices because of their historical connections. Delicate lustre imitating mother-of-pearl was produced by Wedgwood and at Belleek in the mid-century, derived from bismuth nitrate.[18]

Under the impetus of the Aesthetic Movement, William de Morgan revived lustrewares in a manner drawing from lustred majolica and Hispano-Moresque wares, with fine, bold designs.[19]

In the United States, copper lusterware became popular because of its lustrousness. Apparently, as gaslights became available to the rich, the fad was to place groupings of lusterware on mirror platforms to be used as centerpieces for dinner parties. Gaslights accentuated their lustrousness.

.jpg) Sugar bowl from a coffee-set, French faience from Sarreguemines, c. 1810

Sugar bowl from a coffee-set, French faience from Sarreguemines, c. 1810 English urn for the American market, 19th century

English urn for the American market, 19th century Vase by William de Morgan, 1888-98, English

Vase by William de Morgan, 1888-98, English- Belgian vase, 20th century

See also

- Eosin

- List of pottery terms

Notes

- Peck, Elsie Holmes (1997). "Like the Light of the Sun: Islamic Luster-Painted Ceramics". Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts. 71 (1/2): 17–18. doi:10.1086/DIA41504933. ISSN 0011-9636. JSTOR 41504933.

- Caiger-Smith, Chapters 6-8

- SABA, MATTHEW D. (2012). "Abbasid Lusterware and the Aesthetics of ʿajab". Muqarnas. 29: 187–212. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000187. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 23350366.

- George, Alain (2015-10-15). "Direct Sea Trade Between Early Islamic Iraq and Tang China: from the Exchange of Goods to the Transmission of Ideas". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 25 (4): 582, 605. doi:10.1017/S1356186315000231. ISSN 1356-1863.

- Caiger-Smith, 80-84; Blair & Bloom, 171

- Fatemeh Shokri, Atefeh Rezvan-Nia (28 September 2015). "Iran origin of Lusterware - Iran Daily". Gale General Onefile. SyndiGate Media Inc. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Darque-Ceretti, E.; Hélary, D.; Bouquillon, A.; Aucouturier, M. (July 19, 2013). "Gold like lustre: nanometric surface treatment for decoration of glazed ceramics in ancient Islam, Moresque Spain and Renaissance Italy". Surface Engineering. 21 (Abstract): 352–358. doi:10.1179/174329305x64312. ISSN 0267-0844.

- Reiss, Gunter; Hutten, Andreas (2010). "Magnetic Nanoparticles". In Sattler, Klaus D. (ed.). Handbook of Nanophysics: Nanoparticles and Quantum Dots. CRC Press. pp. 2–1. ISBN 9781420075458.

- Khan, Firdos Alam (2012). Biotechnology Fundamentals. CRC Press. p. 328. ISBN 9781439820094.

- SABA, MATTHEW D. (2012). "Abbasid Lusterware and the Aesthetics of ʿajab". Muqarnas. 29: 187–212. doi:10.1163/22118993-90000187. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 23350366.

- Peck, Elsie Holmes (1997). "Like the Light of the Sun: Islamic Luster-Painted Ceramics". Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts. 71 (1/2): 17–18. doi:10.1086/DIA41504933. ISSN 0011-9636. JSTOR 41504933.

- George, Alain (2015-10-15). "Direct Sea Trade Between Early Islamic Iraq and Tang China: from the Exchange of Goods to the Transmission of Ideas". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 25 (4): 582, 605. doi:10.1017/S1356186315000231. ISSN 1356-1863.

- Hancock's memoir, quoted by Ross Taggart, The Frank P. and Harriet C. Burnap Collection of English Pottery in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, rev. ed. (Kansas City) 1967, p. 167.

- Aqua regia, a mixture of nitric and hydrochloric acid.

- Technical description from Taggart 1967:168.

- Taggart 1967:169.

- Silver was produced from platinum salts; fully lustred teasets imitating silver models were introduced in 1823 for middle-class households (L.G.G. Ramsey, ed. The Connoisseur New Guide to Antique English Pottery, Porcelain and Glass p. 70.

- John Fleming and Hugh Honour, Dictionary of the Decorative Arts, 1977, s.v. "Lustre".

- Caiger-Smith, 168-170

References

- Blair, Sheila, and Bloom, Jonathan M., The Art and Architecture of Islam, 1250–1800, 1995, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300064659

- Caiger-Smith, A., Lustre Pottery: Technique, Tradition and Innovation in Islam and the Western World, 1985, Faber & Faber

- John, W.D., and Warren Baker, Old English Lustre Pottery (Newport), n.d. (ca 1951).

Further reading

- "Brilliant Achievements: The Journey of Islamic Glass and Ceramics to Renaissance Italy", in The Arts of Fire: Islamic Influences on Glass and Ceramics of the Italian Renaissance, eds. Catherine Hess, Linda Komaroff, George Saliba, J. Paul Getty Museum, 2004, Getty Publications, ISBN 089236758X, 9780892367580,

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lustreware. |

- Nishapur: Pottery of the Early Islamic Period, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on lusterware

.jpeg)