Luke 10

Luke 10 is the tenth chapter of the Gospel of Luke in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It records the sending of seventy disciples by Jesus, the famous parable about the Good Samaritan, and his visit to the house of Mary and Martha.[1] The book containing this chapter is anonymous, but early Christian tradition uniformly affirmed that Luke composed this Gospel as well as Acts.[2]

| Luke 10 | |

|---|---|

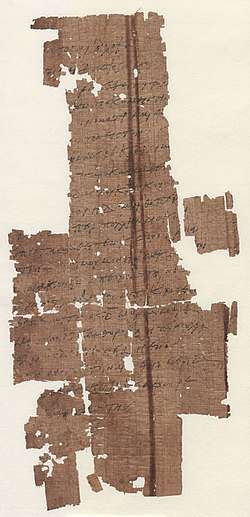

The Latin text of Luke 10:41-11:5 in Codex Claromontanus V, from 4th or 5th century. | |

| Book | Gospel of Luke |

| Category | Gospel |

| Christian Bible part | New Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 3 |

Text

The original text was written in Koine Greek. This chapter is divided into 42 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter are:

- Papyrus 75 (written about AD 175-225)

- Papyrus 45 (c. 250)

- Codex Vaticanus (325-350)

- Codex Sinaiticus (330-360)

- Codex Bezae (c. 400)

- Codex Washingtonianus (c. 400)

- Codex Alexandrinus (400-440)

- Codex Ephraemi Rescriptus (c. 450)

- Papyrus 3 (6th/7th century; extant verses 38-42)[3]

Old Testament references

Narrative of the Seventy

Theologian Heinrich Meyer calls this section the "Narrative of the Seventy" and links it to the earlier account of the sending out of advance messengers in Luke 9:52.[5]

The Parable of the Good Samaritan

This parable is recounted only in this chapter of the New Testament. A lawyer or 'expert in the law' asked Jesus to explain who his 'neighbour' is, referring to the ordinance of Leviticus 19:18:

- You shall not take vengeance, nor bear any grudge against the children of your people, but you shall love your neighbor as yourself.[6]

In response, Jesus told a story of a traveller (who may or may not have been a Jew [7]) who is beaten, robbed, and left half dead along the road. First a priest and then a Levite come by, but both avoid the man. Finally, a Samaritan comes by. Samaritans and Jews generally despised each other, but the Samaritan helps the injured man.

Portraying a Samaritan in a positive light would have come as a shock to Jesus's audience.[8] Some Christians, such as Augustine and John Newton,[9] have interpreted the parable allegorically, with the Samaritan representing Jesus Christ, who saves the sinful soul.[10] Others, however, discount this allegory as unrelated to the parable's original meaning,[10] and see the parable as exemplifying the ethics of Jesus.[11]

The parable has inspired painting, sculpture, poetry and film. For example, Vincent van Gogh's painting, The Good Samaritan, after Delacroix 1890, captures the reverse hierarchy of Luke's parable. Although the priest and Levite are near the top of the status hierarchy in Israel and the Samaritans near the bottom, van Gogh reverses the traditional hierarchy in his painting. He foregrounds the Samaritan, transforming him into a colorful figure who is larger than life, while the priest and Levite are in the background, small and insignificant.[12] The colloquial phrase "good Samaritan", meaning someone who helps a stranger, derives from this parable, and many hospitals and charitable organizations are named after the Good Samaritan.

Mary and Martha

In Luke's account, the home of Martha and Mary is located in 'a certain village'.[13] Bethany is not mentioned and would not fit with the topography of Jesus' journey to Jerusalem, which at this point in the narrative is just commencing as he leaves Galilee. John J. Kilgallen suggests that "Luke has displaced the story of Martha and Mary".[14]

See also

References

- Halley, Henry H. Halley's Bible Handbook: an Abbreviated Bible Commentary. 23rd edition. Zondervan Publishing House. 1962.

- Holman Illustrated Bible Handbook. Holman Bible Publishers, Nashville, Tennessee. 2012.

- Aland, Kurt; Aland, Barbara (1995). The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism. Erroll F. Rhodes (trans.). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8028-4098-1.

- Kirkpatrick, A. F. (1901). The Book of Psalms: with Introduction and Notes. The Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Book IV and V: Psalms XC-CL. Cambridge: At the University Press. p. 839. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Meyer, H. (1873), Meyer's NT Commmentary on Luke 10, accessed 12 June 2012

- Leviticus 19:18

- Joel B. Green, The Gospel of Luke, Eerdmans, 1997, ISBN 0-8028-2315-7, p. 429.

- Funk, Robert W., Roy W. Hoover, and the Jesus Seminar. The five gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. 1993. "Luke" p. 271-400

- Newton, J., The Good Samaritan, accessed 13 June 2018

- Caird, G. B. (1980). The Language and Imagery of the Bible. Duckworth. p. 165.

- Sanders, E. P., The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin, 1993. p. 6.

- James L. Resseguie, Narrative Criticism of the New Testament: An Introduction (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), 26-30 at p. 29.

- Luke 10:38

- Kilgallen, J. J., Martha and Mary: Why at Luke 10,38?, Biblica, Vol. 84, No. 4 (2003), pp. 554-561

External links

- Luke 10 King James Bible - Wikisource

- English Translation with Parallel Latin Vulgate

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Multiple bible versions at Bible Gateway (NKJV, NIV, NRSV etc.)

| Preceded by Luke 9 |

Chapters of the Bible Gospel of Luke |

Succeeded by Luke 11 |