Laugharne

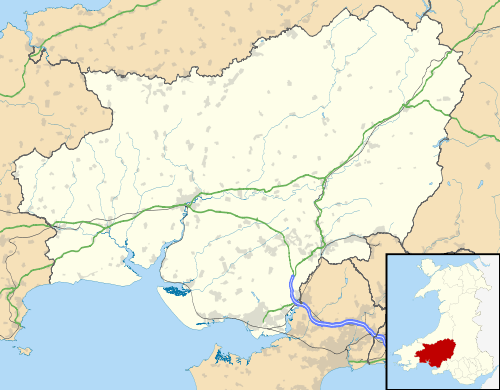

Laugharne /ˈlɑːrn/ (Welsh: Talacharn) is a town on the south coast of Carmarthenshire, Wales, lying on the estuary of the River Tâf.

Laugharne

| |

|---|---|

.jpg) Laugharne from the castle | |

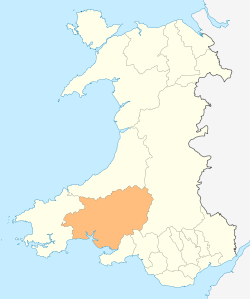

Laugharne Location within Carmarthenshire | |

| Population | 817 |

| OS grid reference | SN301109 |

| Community |

|

| Principal area | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Country | Wales |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | CARMARTHEN |

| Postcode district | SA33 |

| Police | Dyfed-Powys |

| Fire | Mid and West Wales |

| Ambulance | Welsh |

The ancient borough of Laugharne Township (Welsh: Treflan Lacharn) with its Corporation and Charter[1] is a unique survival in Wales. In a predominantly English-speaking area, just south of the Landsker Line, the community is bordered by those of Llanddowror, St Clears, Llangynog and Llansteffan. It had a population at the 2011 census of 1,222.[2] Laugharne Township electoral ward also includes the communities of Eglwyscummin, Pendine and Llanddowror.[3]

Dylan Thomas lived in Laugharne from 1949 until his death in 1953, famously describing it as a "timeless, mild, beguiling island of a town".[4] It is generally accepted as the inspiration for the fictional town of Llareggub in Under Milk Wood. Thomas himself confirmed on two occasions[5] that his play was based on Laugharne although topographically it is also similar to New Quay where he briefly lived.[6]

History

Laugharne was originally in Gwarthaf, the largest of the seven cantrefi of the Kingdom of Dyfed in southwest Wales, and subsequently became part of Deheubarth. In 1093, Deheubarth was seized by the Normans following Rhys ap Tewdwrs death.[7] In the early 12th century, grants of lands were made to Flemings by King Henry I when their country was flooded.[8]

In 1116, when Gruffydd ap Rhys (the son and heir of Rhys ap Tewdwr) returned from self-imposed exile, the king arranged for the land to be fortified against him; according to the Brut y Tywysogyon, Robert Courtemain constructed a castle at Laugharne in that year[9] (this is the earliest reference to any castle at or near Laugharne[10]). Courtemain may be the Robertus cum tortis manibus (English: Robert with twisted hands)[11] mentioned in the Book of Llandaff, as one of a number of specifically named Norman magnates[notes 1] within the vicinity of the Llandaff diocese, who received a letter from Pope Callixtus II complaining about deprivations they had inflicted on diocesan church property;[11] in the letter, the Pope warns he would confirm Bishop Urban's proclamations against them, if they do not rectify matters. The Brut states that Courtemain appointed a man named Bleddyn ap Cedifor as castellan;[9] Bleddyn was the son of Cedifor ap Gollwyn, descendant and heir of the earlier kings of Dyfed (as opposed to those of Deheubarth).[9][12] The castle was originally known as Abercorran Castle.[13]

When Henry I died, Anarchy occurred, and Gruffydd, and his sons, Lord Rhys in particular, gradually reconquered large parts of the former Deheubarth. In 1154, the Anarchy was resolved when Henry II became king; two years later, Lord Rhys agreed peace terms with Henry II and prudently[14] accepted that he would only rule Cantref Mawr,[14] constructing Dinefwr Castle there. Henry II de-mobilised Flemish soldiers who had aided him during the Anarchy, settling them with the other Flemings.[8]

From time to time, however, King Henry had occasion to go to Ireland, or Normandy, which Lord Rhys took as an opportunity to try and expand his own holdings. Returning from Ireland after one such occasion, in 1172, King Henry made peace with Lord Rhys, making him the justiciar of South Wales (ie. Deheubarth). By 1247, Laugharne was held by Guy de Bryan; this is the earliest reference to his family possessing the castle,[10] and his father (also named Guy de Bryan) had only moved the family to Wales in 1219 (from Devon).[10] Guy de Bryan's descendants continued to hold the castle; his namesake great-grandson was Lord High Admiral of England. The latter's daughter Elizabeth inherited the castle and married an Owen of St Bride's who subsequently took his name – Owen Laugharne – from the castle[15] despite Gerald of Wales calling the castle Talachar, and other variations on Laugharne/Talacharn appearing in ancient charters; one anonymous pre-20th century writer erroneously claimed that the Owen Laugharne gave his name to the castle rather than the other way around.[15]

Possession subsequently defaulted to the Crown, and in 1575, Queen Elizabeth gave it to Sir John Perrot.[10] In 1644 the castle was garrisoned for the king and taken for Parliament by Major-General Rowland Laugharne, who subsequently reverted to the king's side. [16]

The population in 1841 was 1,389.[17]

Laugharne Corporation

Laugharne Corporation is an almost unique institution and, together with the City of London Corporation, the last surviving mediæval corporation in the United Kingdom. The Corporation was established in 1291 by Sir Guy de Brian (Gui de Brienne), a Marcher Lord.[18] The Corporation is presided over by the Portreeve, wearing his traditional chain of gold cockle shells, (one added by each portreeve, with his name and date of tenure on the reverse), the Aldermen, and the body of Burgesses. The title of portreeve is conferred annually, with the Portreeve being sworn in on the first Monday after Michaelmas at the Big Court. The Corporation holds a court leet half-yearly formerly dealing with criminal cases, and a court baron every fortnight, dealing with civil suits within the lordship, especially in matters related to land, where administration of the common fields was dealt with.[18] The Laugharne open field system is one of only two surviving and still in use today in Britain.

'In Elizabeth's reign the lordship passed to Sir John Perrott of Haroldston, a fact for which the inhabitants of Laugharne have had cause to regret. As at Carew Perrot modernised the castle, but he was the most unscrupulous "land-grabber" of his age, and in 1574 he induced the burgesses to part with three hundred acres of land in return for an annuity of £ 9 6s. 8d. The records say that "diverse burgesses of the said towne did not assent to same", and that it was "to the great decaying of many". It would be interesting to know by what methods of bribery or intimidation Sir John was able to accomplish his nefarious purposes.'[19]

The most senior 76 burgesses get a strang of land on Hugden for life, to be used in a form of mediaeval strip farming. Customs associated with the Corporation include the Common walk (also known as beating the bounds), which occurs on Whit Monday every three years. This event is attended by most of the young and firm local population, their number swelled by many visitors. The local pubs open at approx 5.00 in the morning, and following a liquid breakfast the throng commence a trek of some 25 miles around the boundaries of the Corporation lands. At significant historical landmarks a victim is selected to name the place. If they cannot answer, they are hoisted upside down and ceremonially beaten three times on the rear. The chief toast at the Portreeve's feast is "to the immortal memory of Sir Guido de Brian". After the toast the Recorder must sing the following song:

When Sir Guy de Brien lived in Laugharne,

A jolly old man was he.

Some pasture land he owned, which he

Divided into three.

Says he "There's Hugdon and the Moor

They will the Commons please;

And all the gentlemen shall have

Their share down on the Lees."[21]

Laugharne Corporation holds extensive historical records.[22]

St Martin's Church

The parish church of St Martin dates from the 14th century when it was built by the Lord of the Manor of Laugharne Sir Guido de Brian, who also built the Church of St Margaret Marloes, Eglwyscummin some 5 miles (8.0 km) to the west.[23]

The church is situated within a rectilinear churchyard, bounded by former strip fields, extending some 200 metres (660 ft) to the south and 400 metres (1,300 ft) to the east. It is thought that the church's original dedication was to St Michael, as it was reportedly referred to by this name in 1494 and 1849. Cist burials have reportedly been identified in the churchyard. A small, ornamented wheel-topped stone was reportedly excavated during grave-digging. At the time of the foundation borough of Laugharne, by a charter of 1278, the church belonging to the Rural Deanery of St Clears and a prebend of Winchester Cathedral. Before 1777 the churches of St Lawrence's Church, Marros and St Cyffic's Church, Cyffic were dependencies, but these both then became parish churches in their own right. In 1927 a medieval tile and what is thought to have been part of a canopied tomb were found in the churchyard. The churchyard's eighteenth and nineteenth century monuments in the churchyard are Grade II listed for their group value.[24]

Inside the church is a shaped cross-slab dating from the Dark Ages, probably the 9th-10th century, built into the east wall of the south transept and has an unusual Celtic design carved onto it. Some historians claim the design is of Viking origin. There is thick ropework, in the form of looped interlacing, running up from the bottom to the cross-head. Close to the edges there is thinner knotwork. The large round-shaped cross-head has a Latin-style cross in the centre with a small boss in the middle of that and oval looped links between the arms.[23]

The church is today part of the United Benefice of Bro Sancler. Welsh poet and playwright Dylan Thomas is buried in the churchyard, his grave marked by a white cross.[23][24][25]

Other landmarks

Local attractions include the 12th-century Laugharne Castle, the town hall and the estuary birdlife.[26]

Laugharne contains many fine examples of Georgian townhouses including "Great House" and Castle House, both grade II* listed buildings, with a scattering of earlier vernacular cottages.[27]

There are a number of landmarks in Laugharne connected with the poet and writer Dylan Thomas. These include: The Boathouse, where he lived with his family from 1949 to 1953, and now a museum; his writing shed; and the Dylan Thomas Birthday Walk, which was the setting for the work Poem in October.[28]

In popular culture

Many scenes in the 2017 TV series Keeping Faith (broadcast in Welsh as Un Bore Mercher) were shot in and around Laugharne, which is referred to as Abercorran.[29]

Laugharne weekend

Laugharne hosts a three-day arts festival in the spring, the Laugharne Weekend. The festival's inauguration was in 2007, featuring writers such as Niall Griffiths and Patrick McCabe. Headline performers since then have included Ray Davies, Will Self, Howard Marks and Patti Smith. Although the town's Millennium Hall was used as the main venue, smaller events were hosted by local venues including Dylan Thomas's Boathouse.[30]

Notable people

- Sir John Perrot (1528-1592), Lord Deputy of Ireland, Lord President of Munster and Privy Councillor to Elizabeth I, lived in Laugharne Castle[31]

- Sir Thomas Perrot (1553-1594) Elizabethan courtier, soldier and Member of Parliament, lived in Laugharne Castle[32]

- Sir James Perrot (1571-1636) writer and Member of Parliament, lived in Laugharne[notes 2]

- Sir Sackville Crowe (1595-1671) English politician, lived in Laugharne.[35]

- Rowland Laugharne (1607-1675), Parliamentary General, his 1644 seige of the castle, a former family home, left it an uninhabitable ruin.[36]

- Bishop William Thomas (1613-1689) Vicar of Laugharne, ejected by Cromwell. Later Bishop of St Davids and Bishop of Worcester.[37]

- Sir John Powell (1632/3–1696), judge who presided over the trial of the Seven Bishops in 1688, lived in Laugharne[38]

- Sir Thomas Powell (c.1665–1720), lawyer and Member of Parliament, born in Laugharne[39]

- Griffith Jones (1684–1761), educational pioneer, resided with Bridget Bevan in Laugharne in his later years[40]

- Bridget Bevan (1698–1779), also known as Madam Bevan, educationalist and philanthropist, lived in Laugharne[41]

- Josiah Tucker (1713–1799), clergyman, economist and political writer. Dean of Gloucester, born in Laugharne[42]

- Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), writer, philosopher, and advocate of women's rights, lived in Laugharne as a child[43]

- James Augustus St. John (1795–1875), author and traveller, born in Laugharne

- Arnold Wienholt, Sr. (1826–1895), Australian politician, born in Laugharne[44]

- Edward Wienholt (1833–1904), Australian politician, born in Laugharne[45]

- Agnes Mason (1849–1941), nun, born in Laugharne[46]

- Joseph Arthur Hamilton Beresford (1861–1952), Australian naval commander, born in Laugharne[47]

- William Charles Fuller VC (1884–1974), soldier, born in Laugharne

- Richard Hughes (1900–1976), writer, lived in Castle House, instrumental in Dylan Thomas moving to Laugharne[48]

- Dylan Thomas (1914–1953), poet, lived in Laugharne and is buried in the churchyard[49]

- Sir Kingsley Amis (1922-1925), novelist, poet, critic and teacher, wrote Booker Prize winner The Old Devils while living in Cliff House, Laugharne. [50]

- George Tremlett (born 1939), writer, former politician and bookshop owner, lives in Laugharne[51]

- Gary Pearce (born 1960), rugby union and rugby league player, born in Laugharne[52]

Notes

- The other named magnates are Walter fitz Richard, Brian Fitz Count, William Fitz-Baldwin (son of Baldwin FitzGilbert), Robert de Chandos (who held Caerleon), Geoffrey de Broi, Pain fitzJohn, Bernard de Neufmarche, Gumbald of Ludlow, Roger de Berkeley (Lord of Dursley, and possible son of Roger I of Tosny), William the sheriff of Cardiff, William Fitz-Roger de Remu, and Robert Fitz Roger.

- James Perrot's father described him as being 'late' of Westmead.[33] Westmead was a mansion house near the later village of Llanmiloe and was within the parish of Laugharne.[34]

References

- "History of Laugharne Charter". Laugharne Corporation 2010.

- "Community population 2011". Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- "Carmarthenshire County Council: Policy, Research and Information Section" (PDF). Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Dylan Thomas on Laugharne". Dylan Thomas The Official Website. The City and County of Swansea. 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Letters to John Ormond March 6, 1948 and Princess Caetani, October 1951

- "Under Milk Wood – A Chronology". Dylan Thomas The Official Website. The City and County of Swansea. 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- Jones, John (1824). The History of Wales, Descriptive of the Government, Wars, Manners, Religion, Laws, Druids, Bards, Pedigrees and Language of the Ancient Britons and Modern Welsh, and of the Remaining Antiquities of the Principality. London: J. Williams. pp. 63–64. OL 7036828M. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Tyler, R. H.; et al. (1985) [1925]. Laugharne: Local History and Folklore. Llandysul: Gomer Press. ISBN 9780863831546. Compiled by Head, Senior Assistant and senior pupils of Laugharne School

- Davies, R. R. (1987). Conquest, Coexistence, and Change: Wales 1063–1415. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 101. ISBN 0198217323.

- Avent, Richard (2006). "Laugharne Castle". In Lloyd, Thomas; Orbach, Julian; Scourfield, Robert (eds.). Carmarthenshire and Ceredigion. The Buildings of Wales. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 219–27 (219–220). ISBN 9780300101799.

- Lloyd, John Edward (1907). "Carmarthen in Early Norman Times". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 6th ser. 7: 290.

- Davies, R. R. (2000). The Age of Conquest: Wales, 1063–1415. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 0198208782.

- "RCAHMW: Abercorran Castle". Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Venning, Timothy (2017). Kingmakers: How Power in England Was Won and Lost on the Welsh Frontier. Stroud: Amberley. ISBN 9781445659404.

- "Notices of the castle and ownership of Laugharne, Carmarthenshire". Gentleman's Magazine. 12: 602. 1839.

- Sieges of Laugharne Castle by S Lloyd (2013)Report for CADW & RCAMW

- The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.III, London, (1847), Charles Knight, p.1,012

- "Laugharne Corporation Records - Archives Hub". archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- Archaeologia Cambrensis, Vol. 100, (1948-49) Prof. David Williams: Introduction to Laugharne.

- Baker, Alan R. H.; Butlin, Robin A., eds. (1973). Studies of Field Systems in the British Isles. Cambridge University Press. pp. 512–514. ISBN 978-0-521-20121-6.

- Rees, Anne (Summer 1991). "Laugharne Corporation and the Perrots". Laugharne Perrott Family Notes. pp. 89–91.

- Carmarthenshire Archives Service website

- Sunny100 (3 October 2011). "St Martin's Church (Laugharne)". The Megalithic Portal. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "ST MARTIN'S CHURCH, LAUGHARNE - Coflein". www.coflein.gov.uk. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- Wales, The Church in. "Churches". The Church in Wales. Retrieved 27 December 2018.

- "Laugharne Castle". Visit Wales. The Welsh Government. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- "Listed Buildings in Laugharne Township, Carmarthenshire, Wales". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 20 December 2013.

- "Dylan Thomas' Laugharne". Visit Wales. The Welsh Government. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- Robert Harries, 19 April 2017, 'Filming for new TV drama gets under way in historic Carmarthen building' walesonline.co.uk. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- Laugharne Weekend website

- "Church Monument Society: Sir John Perrot". Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Indenture from John God to Sir John Perrot, cited in

"Notes on the Perrot Family". Archaeologia Cambrensis. Cambrian Archaeological Association (XLVII): 324. July 1866.No. 26334. An indenture made 12 Elizabeth, in which John God, merchant tailor of London, makes over to Sir John Perrot the parsonage of Laugharne. (In this document Sir John is described as late of Carew.)

- Turvey, Roger (2002). "Admiration or Revulsion: Interpreting the Life, Career and Character of Sir James Perrot (1571-1637), Part One". The Journal of the Pembrokeshire Historical Society (11): 7. ISSN 1355-0152. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- "Pendine and Llanmiloe". Dyfed Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 20 June 2020.

- Davidson, Alan; Thrush, Andrew (2010). "CROWE, Sackville (1595-1671), of Laugharne, Carm.; formerly of Brasted Place, Kent and Mays, Selmeston, Suss.". In Thrush, Andrew; Ferris, John P. (eds.). The House of Commons, 1604-1629. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107002258.

Accessed via "CROWE, Sackville (1595-1671), of Laugharne, Carm.; formerly of Brasted Place, Kent and Mays, Selmeston, Suss". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 24 June 2020. - Sieges of Laugharne Castle by S Lloyd (2013)Report for CADW & RCAMW

- Roberts, Stephen K. (October 2005). "Thomas, William (1613–1689)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online edition, subscription access). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 16 March 2008.

- Roberts, G. (1959). POWELL, Sir JOHN (1633-1696), lawyer and judge. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Hayton, D. W. (2002). "POWELL, Sir Thomas, 1st Bt. (c.1665-1720), of Broadway, Laugharne, Carm. and Coldbrook Park, Mon.". In Cruickshanks, Eveline; Handley, Stuart; Hayton, D. W. (eds.). The House of Commons, 1690-1715. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521772211.

Accessed via "POWELL, Sir Thomas, 1st Bt. (c.1665-1720), of Broadway, Laugharne, Carm. and Coldbrook Park, Mon". The History of Parliament. Retrieved 24 June 2020. - Clement, M. (1959). JONES, GRIFFITH (1683 - 1761), cleric and educational reformer. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Clement, M. (1959). BEVAN, BRIDGET (‘Madam Bevan’; 1698 - 1779), philanthropist and educationist. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Rees, J. F., & Jenkins, R. T. (1959). TUCKER, JOSIAH (1712 - 1799), cleric and economist. Dictionary of Welsh Biography. Retrieved 19 June 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Johnson, Claudia L. (2006). The Cambridge Companion to Mary Wollstonecraft (PDF). Cambridge University Press. p. xv. ISBN 9780511998812.

- "Wienholt, Arnold (Snr)". Parliament of Queensland. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Wienholt, Edward (1833–1904) – Australian Dictionary of Biography Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- Julia Bolton Holloway, ‘Mason, (Frances) Agnes (1849–1941)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 accessed 12 Nov 2016

- "Former R.A.N. Man Dies at Hobart". The Mercury. CLXXII (25, 593). Tasmania. 31 December 1952. p. 7.

- "Dylan Thomas' Laugharne". Wales Arts. BBC. 6 November 2008. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013.

- Ferris, Paul (1989). Dylan Thomas, A Biography. New York: Paragon House. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-55778-215-1.

- Dylan Thomas Centre Laugharne

- Beale, Nigel. "George Tremlett on Dylan and Caitlin Thomas". The Biblio File.

- "Rugby in Wales: Laugharne FC". Retrieved 22 June 2020.