Kokota language

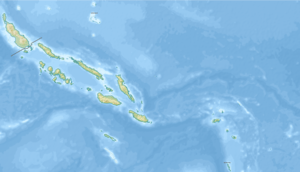

Kokota (also known as Ooe Kokota) is spoken on Santa Isabel Island, which is located in the Solomon Island chain in the Pacific Ocean. Santa Isabel is one of the larger islands in the chain, but it has a very low population density. Kokota is the main language of three villages: Goveo and Sisigā on the North coast, and Hurepelo on the South coast, though there are a few speakers who reside in the capital, Honiara, and elsewhere. The language is classified as a 6b (threatened) on the Graded Intergenerational Disruption Scale (GIDS). To contextualize '6b', the language is not in immediate danger of extinction since children in the villages are still taught Kokota and speak it at home despite English being the language of the school system. However, Kokota is threatened by another language, Cheke Holo, as speakers of this language move, from the west of the island, closer to the Kokota-speaking villages. Kokota is one of 37 languages in the Northwestern Solomon Group, and as with other Oceanic languages, it had limited morphological complexity. [1]:3

| Kokota | |

|---|---|

| Ooe Kokota | |

| Native to | Solomon Islands |

| Region | 3 villages on the Island Santa Isabel: Goveo, Sisiḡa, Honiara |

| Ethnicity | Kokota |

Native speakers | 1,200 (2009)[1] |

Austronesian

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | kkk |

| Glottolog | koko1269[2] |

Kokota uses little affixation and instead relies heavily on cliticization, full and partial reduplication, and compounding. Phonologically, Kokota has a diverse array of vowels and consonants and makes interesting use of stress assignment. Regarding its basic syntax, Kokota is consistently head-initial. The sections below expand on each of these topics to give an overview of the Kokota language.

Phonology

The phonemic inventory of Kokota consists of 22 consonants and 5 vowels.[1]:5, 14

Vowels

Kokota has five vowel phonemes as shown in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) chart below and uses no phonemic diphthongs.[1]:14 There are two front vowels, /i/ and /e/, one central vowel, /a/, and two back vowels: a maximally rounded /u/ and a slightly rounded /o/.[1]:14

|

Kokota doesn’t contain any phonemic diphthongs; however they do occur in normal speech. Only certain vowel sequences are eligible for diphthonisation. Sequences may only diphthongise if the second vowel present is higher than the first. Front-back and back-front movements are not eligible to become diphthongs. This leaves six diphthongs able to occur (Palmer 1999:21–22): /ae/, /ai/, /ao/, /au/, /ei/ and /ou/. Diphthongisation is also not restricted by morpheme boundaries. Thus, any sequence of eligible vowels may diphthongise.

Consonants

Kokota orthography is heavily influenced by that of Cheke Holo. For instance, glottal stops are not phonemic in Kokota but are often written with an apostrophe (as in Cheke Holo) when they occur in certain nondistinctive environments, such as to mark morpheme boundaries between neighboring vowels. Similarly, Cheke Holo distinguishes j and z but Kokota does not. Nevertheless, Kokota speakers tend to use either letter to write phonemic /z/. The macron is used to write the voiced velar plosive /ɡ/ and the velar nasal /ŋ/.

Most consonants distinguish voiceless and voiced versions (left and right respectively in each cell in the table). Kokota presents a rather uncommon set of consonant phonemes in that each and every phoneme exists in a pair with its voiced or voiceless opposite. There are 22 consonant phonemes in total – 11 place and manner pairs of voiced and voiceless (Palmer 1999:12) and five contrastive manners[1]:5. Two are obstruent classes which are fricative and plosive and three are sonorant classes which are lateral, nasal, and rhotic.[3] Its six fricative phonemes make Kokota a relative outlier in Oceanic, where 2-3 fricatives are usual.[4] The amount of voiced and voiceless consonants and vowels is nearly equal with the percentage being 52% voiced and 48% voiceless.[3]

|

Syllable structure

Kokota uses three types of syllable structure for the most part: V, CV, and CCV. Most (88% of 746 syllables examined) are CV (V and CCV each represent 6%). However, there are also rare cases where a CCVV or CVV syllable may occur. Thus, Kokota structure is: (C)(C)V(V).[1]:20 Final consonant codas usually occur only in words borrowed from another language.[1]:20 The CCVV structure is extremely rare as Kokota does not use phonemic 'diphthongs' and the term simply refers to 2 vowels occurring in sequence in a single syllable. [1]:14 In CC initial syllables, the first consonant (C1) must be an obstruent or fricative, specifically: the labial plosives /p/, /b/, velar plosives /k/, /g/, labial fricatives /f/, /v/, or coronal fricatives /s/, /z/. The second consonant (C2) must be a voiced coronal sonorant ( /ɾ/, /l/, or /n/). The table below illustrates the possible CC onset cluster pairings. [1]:21

| p | b | k | g | f | v | s | z | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ɾ | pɾ | bɾ | kɾ | gɾ | fɾ | vɾ | ?sɾ | zɾ |

| l | pl | bl | kl | gl | fl | - | - | - |

| n | - | bn | kn | - | fn | - | sn | zn |

The table below contains representations of the basic, productive syllable structures in Kokota.

| Template | Instantiation | Translation |

| V | /ia/[1]:49 | 'the' singular |

| CV | /na.snu.ɾi/[1]:21 | 'sea urchin' |

| CCV | /sna.kɾe/[1]:21 | 'allow' |

| CVV | /dou/[1]:25 | 'be.big' |

Stress

Kokota uses trochaic stress patterns (stressed-unstressed in sequence, counting from the left edge of a word). Stress in the language varies widely among speakers, but there are patterns to the variation. Three main factors contribute to this variability: the limited morphology of Kokota, the fact some words are irregular by nature, and finally because of the present transition in stress assignment. The language is currently in a period of transition as it moves from relying on stress assignment based on moras and moves to stress assignment by syllable. The age of the speaker is a defining factor in stress use as members of older generations assign stress based on weight while younger generations assign stress based on syllables, placing main stress on the leftmost syllable of the word. [1]:30

Example 1

Words can be divided into syllables (σ) and feet (φ) and syllables may be divided further into moras (μ). Two moras grouped together comprise a foot. An important restriction on foot formation in Kokota is that their construction cannot split moras of the same syllable. For example, a word that has three syllables CV.CV.CVV has four moras CV, CV, CV, V. These moras are split into two feet: [CV.CV] and [CVV].[1]:31

Assigning stress based on mora uses bimoraic feet to determine where a word receives stress. In CVV.CV words like /bae.su/ ('shark') the syllables are split as bae and su. The word subdivides into three moras: ba, e, su. The first two moras ba and e become Foot 1 and su is a 'left-over' mora. The first mora is stressed (ba), though in speech the whole syllable receives stress so bae is stressed in this word (see below where the stressed syllable is bolded).[1]:33

baesu

φ: bae, -

σ: bae, su

μ: ba, e, su

In contrast, a younger speaker of Kokota would assign stress based on bisyllabic feet. Following the syllable structure above, bae is again the stressed syllable but this is simply coincidental as stress is assigned to the first syllable (of the two: bae.su). This coincidence will not always be the case as demonstrated in the next example, below.

Example 2

CV.CVV words like /ka.lae/ ('reef') show more complex stress assignment. 'ka.lae' has three moras: ka, la, e and two syllables: ka, lae. For older speakers, the feet are assigned differently than in bae.su because ordinary foot assignment would take the first two moras and thus would split the lae syllable. Since this is impossible, foot assignment begins with the second mora and thus the first foot is lae and stress falls on the first mora of that foot (and the rest of the syllable).[1]:33

kalae

φ: - , la e

σ: ka, la e

μ: ka, la, e

A younger speaker uses the simpler, syllable-based foot parsing: stress thus falls on the first syllable ka while the second syllable lae is unstressed.

Verb Complex

In the Kokota language there are two layers to the verb complex: an inner layer and an outer layer. The inner layer is the verb core which is transparent to any sentence modifiers. The outer layer can alter the verb core all together. Constituent modifiers can modify the verb complex in a sentence in addition to the inner and outer layers of verb complexes.[3]

Verb Compounding

Compound verbs stem from multiple verbs. The left-hand root is the verb and the right-hand can be a noun, verb, or adjective. The phrase all together acts as a verb phrase.[3]

| Compound Verbs | verb, noun, or adjective root |

| a.do~dou-n̄hau | 'be a glutton' (lit. 'R.D-be.big-eat') |

| b.lehe-n̄hau | 'be hungry' (lit. 'die-eat') |

| c.gato-ḡonu | 'forget' (lit. 'think-be.insensible') |

| d.foḡra-dou | 'be very sick' (lit. 'be.sick-be.big') |

| e.dia-tini | 'be unwell' (lit. 'be.bad-body') |

| f.turi-tove | 'tell custom stories' (lit. 'narrate-old') |

Table retrieved from, Kokota Grammar by Bill Palmer, Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.[3]

Reduplication

Kokomo shows full and partial reduplication of disyllabic roots.[3]

Partial Reduplication

In some cases partial reduplication shows the change of a noun to a verb; nouns from verbs; slight noun from noun differentiation; slight verb from verb differentiation; derived form of a habitual, ongoing, or diminutive event.

| verb from noun | ||

| a. | /fiolo/ 'penis' | /fi~fiolo/ 'masturbate (of males)' |

| b. | /piha/ 'small parcel' | /pi~piha/ 'make a piha parcel' |

| c. | /puki/ 'round lump of s.th.' | /pu~puki/ 'be round' |

| noun from verbs | ||

|---|---|---|

| a. | /siko/ 'steal' | /si~siko/ ʻthiefʻ |

| b. | /lase/ 'know' | /la~Iase/ 'knowledge, cleverness' |

| c. | /maku/ 'be hard' | /ma~maku/ 'Ieatherjacket (fish w. tough skin)' |

| slight noun from noun differentiation | ||

|---|---|---|

| a. | /baɣi/ 'wing' | /ba~bayi/ 'side roof of porch' |

| b. | /buli/ 'cowrie' | /bu~buli/ 'clam sp.' |

| c. | /tahi/ 'sea' | /ta~tahi/ 'stingray' |

| slight verb from verb differentiation | ||

|---|---|---|

| a. | /ŋau/ 'eat' | /ŋa~ŋau/ 'be biting (of fish)' |

| b. | /pɾosa/ 'slap self w. flipper (turtles)' | /po~pɾosa/ 'wash clothes' |

| c. | /maɾ̥i/ 'be in pain' | /ma~maɾ̥a/ 'be in labor' |

| habitual, ongoing, or diminutive event | ||

|---|---|---|

| a. | /m̥aɣu/ 'be afraid' | /m̥a~m̥aɣu/ 'be habitually fearful' |

| b. | /safɾa/ 'miss' | /sa~safɾa/ 'always miss' |

| c. | /seha/ 'climb' | /se~seha/ 'climb all about' |

Tables retrieved from, Kokota Grammar by Bill Palmer, Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.[3]

Full Reduplication

There is only a small number of full reduplication of disyllabic roots in the Kokota language. Below are examples of full reduplication where the relationship is idiosyncratic:

| a. | /seku/ 'tail' | /seku~seku/ 'black trevally' |

| b. | /ɣano/ 'smell/taste good' | /fa ɣano~ɣano/ ʻbe very goodʻ |

| c. | /mane/ "man, maleʻ | /fa mane~mane/ ʻbe dressed up (man or woman)ʻ |

| d. | /ɣase/ ʻgirl, femaleʻ | /fa ɣase~ɣase/ ʻbe dressed up to show off (woman only)ʻ |

Tables retrieved from, Kokota Grammar by Bill Palmer, Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.[3]

One example shows full reduplication deriving verbs from transitive roots, and nouns from verbs:

| a. | /izu/ ʻread s.th.ʻ | /izu~izu/ ʻbe reading; a readingʻ |

Tables retrieved from, Kokota Grammar by Bill Palmer, Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.[3]

Clause Structure (Syntax)

Syntax in Kokota follows the basic sequential order: Subject -> Verb -> Object.

An example is shown below.[1]:190

ia

theSG

koilo

coconut

n-e

RL-3S

zogu

drop

ka

LOC

kokorako

chicken

'The coconut fell on the chicken.'

Subject: ia koilo n-e Verb: zogu Object: ka kokorako

Equative Clauses

Equative clauses represent a characteristic of the subject in the sentence. In the Kokota language moods are unmarked. In equatives, the subject agreement component in verb clauses are excluded.[3]

Telling the Time

When telling the time; time is the subject. Telling time smaller than an hour is expressed by a NP that expresses the minutes numerically attached to a possessor that expresses the hour. Using the terms like ‘half past’ or ‘quarter to’ cannot be determined in Kokota language.[3]

| A. tanhi [nihau] time how.much | B. tanhi [fitu-gu] time seven-CRD | tanhi [nabata-ai gaha miniti kenu//egu=na time ten-plus five minute frontlbehind=3SGP |

|---|---|---|

| 'What's the time?' | 'The time is seven o'clock.' | 'The time is fifteen minutes to/past seven.' fitu-gu] seven-CRD |

Table retrieved from, Kokota Grammar by Bill Palmer, Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.[3]

Topicalization

The topicalized subject in Kokota language is in the preverbal position. Any subject can be tropicalized but rarely in natural conversation.[3]

| a. ago n-o fa-lehe=au ara

youSG RL-2s Cs-die=ISGO I |

'You are killing me.' |

| b. ia tara=n̄a n-e mai=ne

theSG enemy=IMM RL-3s come=thisR |

'The enemy has come.' |

| c. tito tomoko n-e au=re zelu

three war.canoe RL-3s exist=thoseN PNLOC |

'Three war canoes are at Zelu.' |

| d. manei e beha n̄hen̄he

he 3s NSP be. separate |

'He is different.' |

Table retrieved from, Kokota Grammar by Bill Palmer, Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.[3]

Below is a table of the breakdown position occurrence of the first 100 verbal clauses in a normal text:

| Preverbal topicalized arguments | Focused arguments | Arguments in unmarked position | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2 (28.5%) | 0 | 5 (71.5%) | 7 (100%) |

| S | 8 (15.5%) | 2 (4.0%) | 41 (80.5%) | 51 (100%) |

| O | 1 (5.5%) | 0 | 17 (94.5%) | 18 (100%) |

Table retrieved from, Kokota Grammar by Bill Palmer, Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press, 2008.[3]

Morphology

Nouns

Cliticization

By adding two clitics on to the root noun /dadara/, Kokota specifies who possesses it as well as its proximity, as shown in the gloss below.[1]:85

The gloss of /dadaraḡuine/ is:

dadara

blood

=ḡu=ine

=1SGP=thisR

'this blood of mine'

/Dadara/ is the root meaning 'blood'; /gu/ indicates 1st person singular possessive ("my").[1]:85

A more complex form of cliticization occurs in the example sentence below:[1]:68

gure

nut.paste

foro

coconut.paste

ḡ-e=u=gu

NT-3S=be.thus=CNT

ade

here

titili=o

titili=thatNV

'They made nut and coconut paste here at those standing stones.'

(Notes: the standing stones 'titili' have spiritual significance; NT is the indicator of neutral modality; CNT is continuous; NV refers to something that is not visible)[1]:xxi

Partial Reduplication

Partial reduplication in Kokota generally derives nouns from verbs. Below are two examples:[1]:26

| Example 1 | Example 2 |

|---|---|

| /siko/ "steal" becomes /si~siko/ "thief" | /lase/ "know" becomes /la~lase/ "knowledge" |

Compounding (nouns)

Both endocentric and exocentric compounding occur.

Endocentric Compounding

Endocentric compounding in Kokota results in words that serve the grammatical purpose that one of its constituent words does. There are three examples below.

| Example 1 | Example 2 | Example 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Noun + Noun = Noun

/hiba/ + /mautu/ = /hibamautu/ "eye" + "right.side" = right eye [1]:63 |

Noun + Active Verb = Noun

/vaka/ + /flalo/ = /vakaflalo/ "ship" + "fly" = aircraft [1]:63 |

Noun + Stative Verb = Noun

/mane/ + /dou/ = /manedou/ "man" + "be.big" = important man [1]:63 |

Exocentric Compounding

Exocentric compounding in Kokota results in words that do not serve the grammatical purpose that any of the constituent words do. There are two examples below.

| Example 1 | Example 2 |

|---|---|

| Active Verb + Noun = Proper Noun

/siko/ + /ḡia/ = /sikogia/ "steal" + "lime" = bird (specific species)[1]:64 |

Active Verb + Stative Verb = Noun

/ika/ + /blahi/ = /ikablahi/ "wash" + "be.sacred" = baptism [1]:64 |

Pronouns

There exist four sets of pronominal forms: preverbal subject indexed auxiliaries, post verbal object indexing, possessor indexing and independent pronouns (Palmer 1999:65). Complying with typical Oceanic features, Kokota distinguishes between four person categories: first person inclusive, first person exclusive, second person, and third person. The preverbal subject indexing auxiliaries do not differentiate between singular and plural, whereas possessor and postverbal object indexing do – except in first person inclusive, where no singular is possible (Palmer 1999:65).

Non-Independent: Subject pronouns

The preverbal subject-indexing pronouns do not distinguish number (Palmer 1999:65).

| Person | Singular=Plural |

|---|---|

| 1st person inclusive | da |

| 1st person exclusive | a |

| 2nd person | o |

| 3rd person | e |

Non-Independent: Object pronouns

The object-indexing pronouns are postverbal clitics (Palmer 1999:65).

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person inclusive | =gita | |

| 1st person exclusive | =(n)au | =ḡai |

| 2nd person | =(n)igo | =ḡau |

| 3rd person | =(n)i ~ Ø (null) | =di ~ ri |

Non-Independent: Possessor pronouns

The possessor-indexing pronouns are suffixed to nouns (Palmer 1999:65).

| Person | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person inclusive | -da | |

| 1st person exclusive | -ḡu | -mai |

| 2nd person | -(m)u | -mi |

| 3rd person | -na | -di |

Independent: Focal pronouns

The independent pronouns, however, go one step further and differentiate between singular, dual, trial and plural numbers (Palmer 1999:65).

| Person | Singular | Plural | Dual | Trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st person inclusive | gita (+NUM) | gita-palu | gita-tilo ~ gita+NUM | |

| 1st person exclusive | ara | gai (+NUM) | gai-palu | gai-tilo ~ gai+NUM |

| 2nd person | ago | gau (+NUM) | gau-palu | gau-tilo ~ gau+NUM |

| 3rd person | manei / nai | maneri ~ rei+NUM | rei-palu | rei-tilo ~ rei+NUM |

Possessive Constructions

Similarly to many Oceanic languages, Kokota makes the distinction between alienable possession and inalienable possession.

Inalienable

Inalienable possession consists of possessor indexing enclitics attaching to the nominal core of the possessed noun phrase as follows (Palmer 1999:121)):

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person inclusive | - | -da |

| 1st person exclusive | -ḡu | -mai |

| 2nd person | -mu | -mi |

| 3rd person | -na | -di |

Alienable

Alienable possession is formed with a possessive base that is indexed to the possessor. This entire unit precedes the possessed noun phrase. Alienable possession is further broken down into two categories, consumable, whose base is ge-, and non-consumable, whose base is no- (Palmer 1999:121).

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person inclusive | ge-da | |

| 1st person exclusive | ge-ḡu | ge-mai |

| 2nd person | ge-u | ge-mi |

| 3rd person | ge-na | ge-di |

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person inclusive | no-da | |

| 1st person exclusive | no-ḡu | no-mai |

| 2nd person | no-u | no-mi |

| 3rd person | no-na | no-di |

Negation

In Kokota negative construction is expressed in two ways. [5] One way is through the use of the negative particle ti and the other way is by the means of the subordinating construction that involves the negative existential verb teo meaning ‘not exist’/ ‘be.not’. [5]

Negative particle ti

Negation is constructed when an auxiliary verb is suffixed with the negative participle ti.[6] When the negative particle ti is suffixed onto the auxiliary, it creates a single complex auxiliary as the particle ti also combines with other tense and aspect particles.[6] Depending on the clause type the negative particle ti can occur with or without the subordinating construction to instigate negation in a clause. [6]

The negative particle ti can be used to express negation in many types of clauses including the ‘be thus’ clause, nominal clauses and with equative predicates. [6]

Negation in 'be thus' clause

When the negative particle ti is situated in a ‘be thus’ clause the particle ti suffixes itself onto the auxiliary in the verb complex of the ‘be thus’ clause.[6] The verb complex within the ‘be thus’ clause consist of the single worded verb -u ‘be thus’, the auxiliary, tense and aspect particles.[6] Below is an example that shows how it is done.

| o-ti ḡela an-lau o-ti-u ago |

|---|

| 2.SBJ-NEG resemble thatN-SPC 2.SBJ.NEG-be.thus youSG |

| Don’t be like that. Don’t be like that you. |

This example shows how the negative particle ti is suffixed onto the irrealis auxiliary o and also attached to the ‘be thus’ verb -u to negate the verb complex.

Negation in nominalised clause

When the negative particle ti expresses negation is it usually suffixed onto the auxiliary verb in the nominalised clause. [6] Below is an example of ti in a nominalised clause.

| ka-ia ti mai-na-o-n̵̄a velepuhi kokota n-e-ke au-re keha-re… |

|---|

| LOC-theSG NEG come-3SGP-thatNV-IMM right.way PNLOC RL-3.SBJ-PRF exist-thoseN NSP-thoseN |

| At that non-coming of Christianity [ig. When Christianity had not yet come] some lived in Kokota |

In this example, the particle ti is not suffixed onto an auxiliary. This is because the auxiliary is an irrealis as this is discussing the past.[7] Irrealis auxiliaries are omittable parts of Kokota speech when there is no ambiguity.[8] As this example is not ambiguous, the irrealis auxiliary is omitted.

Negation in equative predicate

The formation of a negative equatives predicates is similar to the ‘be thus’ clause and nominalised clause where the negative particle is suffixed onto the auxiliary of the verb complex. This is demonstrated below.

| n-e-ti ḡazu hogo-na |

|---|

| RL-3.SBJ-NEG wood be.true-3.SGP |

| They’re not true sticks |

Negation in imperative clause

Negation in imperative clauses can be expressed by the negative particle ti or the subordinating construction.[6] However, it is more common to use the negative particle ti to construct negation in an imperative clause as is the most frequently used and preferred strategy. [9] Below is an example of how it is done.

| o-ti fa doli-ni gilia au batari foforu ago |

|---|

| 2SBJ.NEG CS live-3SGO until exist battery new 2SG |

| Don’t turn it on until you have new batteries. |

Subordinating construction

Negation is expressed through the subordinating construction involves the negative existential verb teo. [9] This subordinating construction is commonly used to negate declarative clauses. [9]

Negative existential verb teo

The negative existential verb teo expresses ‘not exist’/ ‘be.not’ and it is the antonym of the positive existential verb au, meaning ‘exist’.[10] Unlike the positive existential verb au that has both locative and existential functions, teo can only function in an existential sense.[10] Below are examples of negation using the negative existential verb teo:

| teo manhari |

|---|

| be.not fish |

| There are no fish |

| teo | ihei | mane | ta | torai | mao | reregi-ni-na |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| be.not | whoever | man | SB | definitely | come | look.after-3SGO-thatN |

| ia | vetula-na | ḡavana | ka-ia | ḡilu-na | nau | gai |

| theSG | rule-3SGP | government | LOC-theSG | inside-3SGP | village | weEXC |

| There isn’t anyone who actually looks after the government’s law in our village | ||||||

In the example above, there is a locative adjunct present. However, it does not modify teo as it is apart of a relative clause. [10] The more literal translation of the example would be ‘Someone who looks after the Government’s law in our village does not exist’. [10] So, the main clause expresses that absence of the subject's as an entity, rather than the subject not being in the location of the village. [10]

The negative existential verb teo is unlike the au as it does not have a locative function.[10] To express that an entity has no presence in a location involves the subordinating construction.[10] Below are two examples. Example 7 exhibits how au functions when in a locative sense. Whereas, Example 8 exhibits the subordinating construction involving teo to show non-presence in a location.

| n-e au buala |

|---|

| RL-3.SBJ exist PNLOC |

| He is in Buala |

| n-e-ge teo ḡ-e au buala |

|---|

| RL-3.SBJ-PRS be.not NT-3.SBJ exist PNLOC |

| He isn’t in Buala [Lit. His being in Buala is not.] |

Negation in declarative clause

Negation is expressed in a declarative clause through subordinating construction.[9] Through this process the declarative clause becomes a subordinated positive declarative clause which complements the negative existential verb teo.[9] Below is an example of a negatived declarative clause.

| Gai teo [ḡ-a mai-u k-ago] |

|---|

| weEXC be.not NT-1.SBJ come-PRG LOC-youSG |

| We will not be coming to you. [Lit. We are not that we are coming to you] |

In this example the subordinated positive declarative clause has been bracketed to show its placement in the main clause in relation to the negative existential verb teo. [11]

Phrases

Below are phrases spoken in Kokota by a native speaker named Nathaniel Boiliana as he reminisced about World War II:[3]

n-e-ge

RL-3SGS-PRS

tor-i

open-TR

b=ana

ALT=thatN

manei

s/he

goi

VOC

'Has he opened it [i.e., started the tape recorder]?'

au

exist

bla

LMT

n-a-ke=u

RL-IEXCS-PF=vbe.thus

[goveo]

PNLOC

banesokeo

PNLOC

'I was living in [Goveo] Banesokeo,'

tana

then

aḡe

go

ira

thePL

mane

man

ta

SBO

zuke

seek

leba

labor

'then the men came to look for labor.'

ḡ-e-la

NT-3s-go

ara-hi

I-EMPH

ka

LOC

vaka

ship

kabani-na

company-3sGP

amerika

PNLOC

'So I was on an American company ship'

aḡe

go

hod-i=au

take-TR=ISGO

banesokeo

PNLOC

'that took me from Banesokeo,'

rauru

go.seaward

raasalo,

PNLOC

kepmasi

PNLOC

'[we] went seaward to Russell, to Cape Masi.'

n-e

RL-3s

la

go

au=nau

exist=lsGO

sare.

therep

au

exist

bla

LMT

ge

SEQ

au

exist

'I went and stayed there. Staying and staying'

ka

LOC

frin̄he=na

work=thatN

mane

man

amerika=re

PNLOC=thoseN

maḡra

fight

maneri

they

'in the work of those American men in the fight.'

gu

be.thus

ḡ-au-gu

NT-exist-CNT

rasalo

PNLOC

e=u

3s=be.thus

'Like that, living on Russell.'

Numerals

The numeral system of Kokota has many typologically odd features and shows significant lexical replacement. In the numbers up to 10, only "7" fitu (< *pitu) is a clear Proto-Oceanic reflex. The higher numerals also alternate between multiples of 10 (e.g. tulufulu "30" from POc *tolu-puluq "3 x 10") and 20 (tilotutu "60" or "3 x tutu"), including two distinct morphemes with the meanings "10" (-fulu from Proto-Oceanic and -salai, used only on numbers above 60 and likely from a substrate) and "20" (varedake "20" and -tutu, also likely from a substrate). Ross describes it as one of the most bizarre numeral systems attested for an Oceanic language.[4]

| 1

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

kaike

palu tilo fnoto ɣaha nablo fitu hana nheva |

10

20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 |

naboto

varedake tulufulu palututu limafulu tilotutu fitusalai hanasalai nhevasalai |

100

1000 |

ɣobi

toga |

|---|

Abbreviations[12]

- separates morphemes

1 first person exclusive

2 second person

3 third person

3SGO third person ‘object’

3SGP third person possessor

CS causative particle

EXC exclusive

IMM immediacy marker

LOC locative preposition

NEG negative particle

NSP non-specific referent

NT neutral modality

PRG progressive aspect

PNLOC location name

PRF perfective aspect

PRS present tense

RL realis modality

RL-3S realis 3rd person subject

SB subordinator

SBJ subject indexing

SG singular

SPC specific referent suffix

that/thoseN nearby category

that/thoseNV not visible category

Notes

- Palmer, Bill (2009). Kokota Grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 9780824832513.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Kokota". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Palmer, Bill. "Kokota Grammar". ProQuest ebrary. University of Hawaii Press. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- Blust, Robert (2005-01-01). "Review of The Oceanic Languages". Oceanic Linguistics. 44 (2): 544–558. doi:10.1353/ol.2005.0030. JSTOR 3623354.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. 246.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. 247.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. 198.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. 202.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. 248.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. 179.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. 249.

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia. p. xx.

References

- Palmer, Bill (1999). Grammar of the Kokota language, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palmer, B. (1999). Kokota Grammar, Santa Isabel, Solomon Islands. (PhD dissertation, University of Sydney, Australia). Retrieved from http://www.smg.surrey.ac.uk/languages/northwest-solomonic/kokota/kokota-grammar/

- Palmer, Bill (2009). Kokota Grammar. Oceanic Linguistics Special Publication No. 35. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3251-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Palmer, B. (2008). Kokota Grammar. Honolulu, US: University of Hawaii Press. Retrieved from http://www.ebrary.com

- Palmer, Bill (2009). Kokota Grammar. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824832513.