Jaime, Duke of Madrid

Jaime de Borbón y de Borbón-Parma, known as Duke of Madrid and as Jacques de Bourbon, Duke of Anjou in France (27 June 1870 – 2 October 1931), was the Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain under the name Jaime III[1] and the Legitimist claimant to the throne of France as Jacques I.

| Jaime de Borbón | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Madrid; Duke of Anjou | |

Jaime de Borbón, 1911 | |

| Born | 7 June 1870 Vevey, Switzerland |

| Died | 2 October 1931 (aged 61) Paris, French Third Republic |

| House | Bourbon |

| Father | Carlos de Borbón |

| Mother | Margarita de Borbón-Parma |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

| Royal styles of Jaime de Borbón | |

|---|---|

.svg.png) | |

| Reference style | His Royal Highness |

| Spoken style | Your Royal Highness |

| Alternative style | Sir |

Family

Don Jaime's royal ancestry and heir to the Carlist king of Spain determined both his material status and political career, while relations along collateral lines – especially with the Austrian Habsburgs and the French Bourbons – were responsible for some twists and turns of his life. He was personal witness to a string of unsuccessful marriages in his family, from that of his grandparents to those of his own parents, his sisters and many of his Habsburg cousins. They might have contributed to Don Jaime's relations with women; though he was attracted to a number of them, Don Jaime never married and probably had no children.[2]

Ancestors

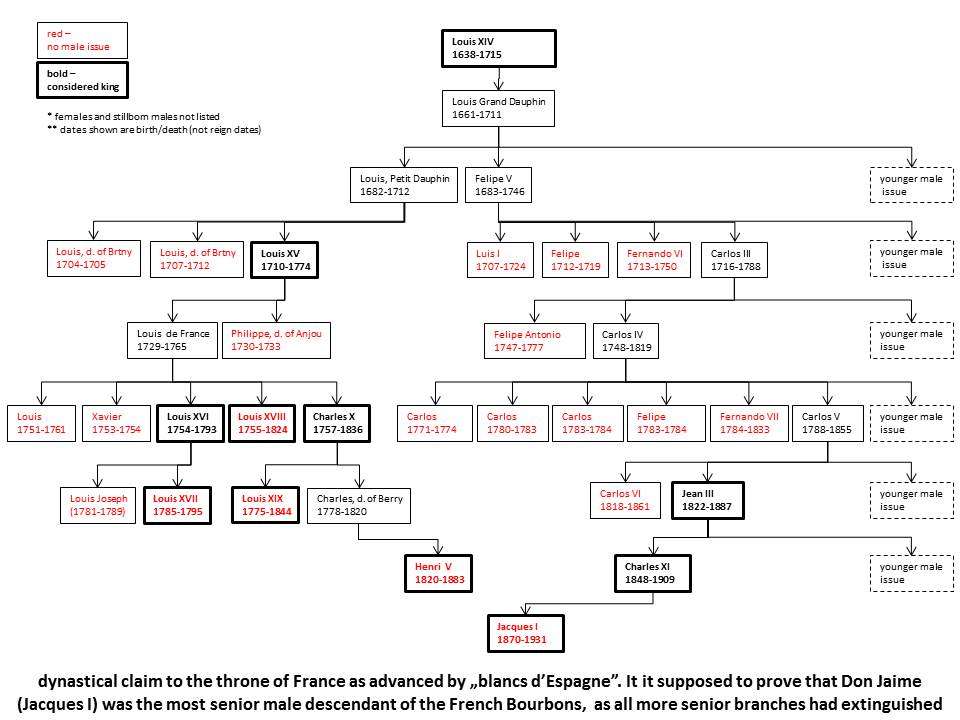

Don Jaime was descended from many highly aristocratic European houses: the Borbóns,[3] the Bourbon-Parmas,[4] the Bourbons,[5] the Borbón-Two Sicilies,[6] the Braganças,[7] the Habsburg-Lothringens,[8] the Austria-Estes,[9] the Savoyans[10] and other.[11] The rate of intermarriage, which posed problems to health of aristocratic offspring, in his case was rather low: instead of 16 great-great-grandparents he had 14.[12] Among them there were 6 kings who actually ruled: Charles IV in Spain (1788–1808), Charles X in France (1824–1830), João VI in Portugal (1822–1826), Francis I in Two Sicilies (1825–1830), Victor Emmanuel I in Sardinia (1802–1821) and Louis I in Etruria (1801–1803). There was one king among his great-grandparents, Louis II of Etruria (1803–1807); having lost his royal status he later reigned as duke Charles I over the Duchy of Lucca (1824–1847) and as Charles II over the Duchy of Parma (1848–1849). Another great-grandfather Francis IV ruled as the Duke of Modena (1814–1846) and another one Carlos V claimed the Spanish throne as a Carlist pretender (1833–1845). Among Don Jaime's grandparents the only one who actually ruled was Charles III, the Duke of Parma (1849–1854), though the Carlist claimant Juan III posed as the king of Spain (1861–1868) and later also as Jean III, the legitimist king of France (1883–1887). Don Jaime's father, Carlos de Borbón (1848–1909), as Carlos VII was the 4th successive claimant to the Carlist throne (1868–1909) and later as Charles XI a legitimist claimant to the French one (1887–1909). Don Jaime's mother, Marguerite de Bourbon-Parme (1847–1893), was daughter to the second-last ruling Duke of Parma and sister to the last ruler of the Duchy of Parma. In 1894 Don Jaime's father remarried with Berthe de Rohan, an Austrian aristocrat and a distant descendant to a branch of French dukes, but the couple had no children.

Uncles, aunts and cousins

All Don Jaime's uncles and aunts came from European royal or ducal families, with two of them actually ruling: the brother of his mother, Roberto I, was the last ruling Duke of Parma (1854–1859), while the sister of his mother, Alicia de Bourbon-Parme, was married to the last ruling Grand Duke of Tuscany Ferdinand IV (1859–1860). Both rulers were deposed in course of unification of Italy and kept claiming the titles when living on exile. Don Jaime's paternal uncle, the brother of his father Alfonso Carlos de Borbón, at the moment of Don Jaime's death became as Alfonso Carlos I the Carlist pretender to the throne of Spain and as Charles XII the legitimist pretender to the throne of France. Count of Chambord, the last strictly patrilinear descendant to the king of France Charles X and as such the legitimist claimant to the throne of France (1844–1883) was distantly related to Don Jaime as both had a common ancestor 6 (in case Count of Chambord) and 7 (in case of Don Jaime) generations earlier; besides, Count of Chambord was married to a sister of Don Jaime's paternal grandmother and was his own godfather.[13] Out of Don Jaime's 33 cousins[14] many concluded highly aristocratic marriages but there were only two who actually ruled: Zita Bourbon-Parme in 1916–1918 was the empress of Austria and the queen of Hungary, while Felix Bourbon-Parme in 1919–1970 was the duke-consort of Luxembourg. A few of his Habsburg-Lothringen cousins were in succession titular claimants to the defunct Grand Duchy of Tuscany, while a few of his Bourbon-Parme cousins were in succession titular claimants to the defunct Duchy of Parma. From 1936 onwards Xavier Bourbon-Parme was the Carlist regent-claimant and later as Javier I the king-claimant of Spain. Some cousins married into royal houses of Italy,[15] Denmark[16] and Saxony.[17] Marriages of Don Jaime's Bourbon-Parme cousins were largely fortunate,[18] while cases of his Habsburg cousins were largely unsuccessful or even scandalous.[19]

Siblings

Don Jaime's sisters did not marry into ruling houses and entered into relations which in 3 out of 4 cases ended up in scandals, attentively followed by European press. The only successful marriage was concluded by his older sister Blanca; in 1889 she married archduke Leopold Salvator of Austria, descendant to a cadet branch of the exiled Tuscan Habsburgs. They had many children and though on exile – after 1918 also from the republican Austria – the couple led a fairly happy family life.[20] Since the 1940s some of their sons posed as Carlist claimants to the throne Spain, related to the so-called Carloctavista branch. The younger sister Elvira was about to marry archduke Leopold Ferdinand Habsburg, son of the 1859-deposed Grand Duke of Tuscany, but due to political reasons the plan was blocked by Emperor Franz Joseph I;[21] in 1896 she fled with an Italian painter Filippo Folchi. Her father announced the daughter "had died for all of us"[22] and the runaway couple with their children shuttled across Europe. Elvira tried to sue her father over inheritance; later she and Folchi parted.[23] It seems that in the late 1920s Don Jaime and Elvira, both living in Paris, maintained some family relationship.[24] One more sister Beatriz in 1892 married Fabrizio Massimo, prince of Roviano, and settled on his estate in Rome. Though with 4 children they were not a happy couple, with constant arguments and her suicide attempt;[25] later the couple kept up appearances but they eventually separated.[26] In 1897 the youngest sister Alicia married Friedrich Schönburg-Waldenburg, a high German aristocrat and owner of many estates in Saxony. Just after giving birth to their only son she abandoned her husband, got the marriage annulled by the Church and in 1903 married an Italian officer Lino del Prete.[27] The couple lived in Tuscany and had 9 children;[28] Alicia was the longest-living one of the siblings and died in 1975.

Own marriage plans and speculations

When he was seventeen Don Jaime was rumoured to marry María, daughter of the late Alfonsist king Alfonso XII.[29] The alleged plan was to mend the feud between the Carlists and Alfonsists, yet there is no indication that the news was anything more than a press speculation.[30] When he was 26, Don Jaime developed at least cordial correspondence with Mathilde, daughter of Prince Ludwig of Bavaria.[31] In unclear circumstances, possibly related to intrigues of his stepmother[32] and political problems with Madrid[33] the relationship dried up. Though when later serving in the Russian army in Warsaw Don Jaime had women in his mind[34] there is no confirmation of any amorous episodes until he was already in his late 30s and subject to concern about lack of Carlist dynastic succession. He was attracted to a 16-year-old Bourbon-Parme cousin Marie-Antoinette,[35] but apparently realised impracticability of the would-be relationship. Don Jaime soon started to pursue[36] her slightly older sister Zita;[37] though some claim that the two were about to get married[38] the girl has never watched her cousin favourably.[39] Rumors related to Patricia Connaught[40] and a niece of Kaiser Wilhelm II[41] followed; there was also a lawsuit about allegedly Don Jaime's son born by his former cook.[42] When he was in his mid-40s the alarm bells were already ringing very loud and succession became a burning political issue. About to turn 50 Don Jaime mounted matrimonial plans focused on Fabiola Massimo, his 19-year-old niece;[43] he already approached the Vatican about a dispensation. The permission has reportedly been denied, either due to protests of his brother-in-law or intrigues of the Madrid court.[44] When he was in his 50s newspapers floated news about Don Jaime's designs related to unnamed "princesas austriacas",[45] "a distinguished French lady"[46] or Blanca de Borbón y León.[47] The last rumours were circulated when aged 58, he was supposed to marry Filipa de Bragança.[48] It seems that at least not all of these speculations should be dismissed as entirely ungrounded.[49]

Childhood and youth

The formative years of Don Jaime are marked by absence of one or another parent; except the years of 1877–1880 the couple spent most of their time apart. Since turning 10 the boy lived away from the family boarded in various educational institutions, meeting his parents and sisters during short holiday spells; the exception were the years of 1886–1889, spent mostly with his mother and siblings in Viareggio. Don Jaime was growing up in rather cosmopolitan ambience, exposed to French, Spanish, German, English and Italian cultures; as a teenager he was already fluent in all these languages.[50]

Childhood

The birth of Don Jaime was celebrated in the Carlist realm as extension of the dynasty, the baby greeted in hunders of messages as the future king of Spain.[51] Initially Jaime remained with his parents and slightly older sister in Palais La Faraz, a mansion occupied by the family in Tour de Peilz near Vevey. In 1871 they moved to Villa Bocage in Geneva,[52] where Jaime's mother gave birth to his another sister. In 1873 Margarita de Borbón, her 3 children and a small quasi-court of assistants, secretaries and servants transferred to Ville du Midi in Pau. At that time Carlos VII was in Spain leading his troops during the Third Carlist War; in 1874 the boy with his mother visited his father on the Carlist-held territory and dressed in uniform, was cheered with frenetic enthusiasm by Carlist soldiers.[53] Upon return to Pau Margarita gave birth to two more daughters before in September 1876[54] the mother, 5 children and royal entourage – including preceptors of the boy[55] – settled in a hotel at Rue de la Pompe in Paris.[56] Don Carlos was mostly travelling, first on a journey to America[57] and then to the Balkans; he joined the family in late 1877. Either in late 1876 or in early 1877 Don Jaime started frequenting Collège de l'Immaculée-Conception at Rue de Vaugirard, a prestigious Jesuit establishment. Initially the boy followed a challenging semi-board pattern; waking up as early as 4:30 am he travelled by public transport to the college and for the night he used to return to his family.[58] This changed in 1880, when due to political pressure of the French government Carlos VII was forced to leave France and settled in Venice.[59] At that time relations between Don Jaime's parents have already turned sour; doña Margarita decided not to accompany her husband and settled in own estate near Viareggio.[60] With his parents away, until completing the curriculum in 1881 the boy lived on the college premises with other students.[61]

Teenager

Following a summer break with his parents in Italy in 1881 Don Jaime entered Beaumont College, prestigious Jesuit establishment in Old Windsor near London.[62] It was catering to Catholic aristocracy from all over Europe, though the largest contingent was formed by Irish boys.[63] Initially Jaime lived with his old preceptor Barrena, who settled in Windsor to facilitiate accommodation even though James Hayes[64] was chosen as a new spiritual guide;[65] in 1882 Barrena left and Jaime moved to common dormitory. As perhaps the most prestigious student[66] he received special treatment.[67] Visited by parents[68] and paternal grandfather, who lived in Brighton,[69] Jaime used to spend holidays in Viareggio or Venice.[70] It seems that his relations with other boys were good, though he tended to patronising[71] and excess of ambition.[72] Don Jaime completed the Beaumont curriculum in May 1886.[73] The same year he inherited from the Chambords part of their fortune and real estates in Austria, in particular the Frohsdorf palace.[74] There were plans about further education in Stella Matutina in Feldkirch, but most of 1887 was spent on recovery from very serious health problems which had plagued him few months earlier;[75] part of the scheme was Don Jaime's trip with his Bardi uncles to Egypt and Palestine.[76] Following return to Viareggio in 1888 he embarked on his first diplomatic mission to Vatican;[77] he was also subject to dynastic speculations related to Nocedalista break-up in Spain[78] and these about his future military education in England and would-be service in India.[79] He seems to have stayed with his mother and sisters in Viareggio rather than with his father in Venice, in 1889 recorded as travelling across Europe either on family business, e.g. to attend the wedding of his sister in Frohsdorf, or on leisure, e.g. with his mother visiting the galleries and museums of Paris.[80]

Early adult years

It is not clear whether Carlos VII has discussed with the British his alleged vision of Don Jaime pursuing a military career in England. Eventually in 1890 Don Jaime indeed commenced military education, though not in Sandhurst but in Theresianische Militärakademie in Wiener Neustadt. Still considered childish by his mother, he was accompanied by a family trustee, Miguel Ortigosa.[81] Almost no details on Don Jaime's military education are available and it is not known whether and if yes what army branch he opted for. According to his later opponents[82] in the academy Don Jaime became loose on his Catholic practices and got somewhat derailed from Traditionalist track.[83] He graduated in 1893,[84] but mounting political differences between Carlos VII and the kaiser produced a disaster: Don Jaime was neither promoted to officer rank nor admitted to the imperial army.[85] The years of 1894–1895 were dedicated mostly to travelling, be it distant voyages like the tour to India, Siam, Indoniesia and the Philippines, or shorter trips, e.g. to the Spanish Morocco.[86] It was in 1894 that for the first time since the early childhood days he visited Spain;[87] officially incognito and accompanied by a Vasco-Navarrese Carlist leader Tirso de Olazábal, during his 37-day tour[88] Don Jaime was many times identified. He gave rise to a number of rather friendly anecdotes,[89] while his journey was widely discussed in the press.[90] Most likely in the mid-1890s Don Carlos explored perspectives of his son commencing a military career in one of major European armies. Don Jaime's service in the imperial Austrian army was out of the question; it is not clear whether the British or the German army was at any point considered an option.[91] Eventually Don Carlos renewed his 1877 relations with the St. Petersburg court and some time late 1895 it was agreed that Don Jaime would join the Russian army.[92]

Warsaw spell

Between April and June 1896[93] Don Jaime joined a cavalry unit in Odessa, where he performed a routine garrison service. In late 1897 he received a transfer order to Warsaw, where he arrived in late March or early April 1898. He spent there almost 6 years on the highly intermittent basis, until he departed for Austria in late 1903. Though in terms of his political career Don Jaime's stay in the city was of little relevance, it is not clear to what extent the service mattered as his formative period.

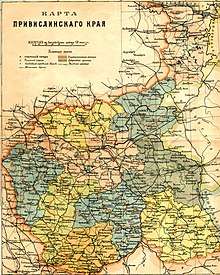

Background

In the late 19th century Warsaw was the third most populous city of the Russian Empire; with almost 700,000 inhabitants, it was larger than Madrid or Barcelona.[94] According to the official 1897 census, 62% of the population were Poles, 27% Jews, 9% Russians and 2% Germans; not a single Spaniard was listed as living in the city.[95] All officialdom, including top administrative layers, schooling, judiciary, and military, was dominated by the Russians. At that time Warsaw was the centre of Vistula Land, a region that retained some minor legal identity but, in general, was well integrated into the Russian administrative structures.[96] The level of national and social tension was relatively low but occasionally noticeable; in 1898, strikes hit the local metalworking industry[97] and in 1899 1 May demonstration turned into riots.[98]

At the turn of the century Warsaw was vital for Russian military planning. The city was headquarters of the westernmost of 14 Russian military districts, and home to a large military garrison.[99] As since the Berlin Congress of 1878 relations with Germany were steadily deteriorating,[100] the area was of growing concern for the Russian General Staff. Itself a prominent salient flanked by German and Austro-Hungarian provinces, it posed a challenge for planners. The prevailing military strategy, known as Miliutin-Obruchev system, pursued a defensive counteroffensive vision;[101] it admitted that initially it might be necessary to abandon territories west of the Vistula and mount a defence based on seven fortresses, of which Warsaw and the other three would form a forward shield.[102]

Military career

Don Jaime arrived in Warsaw following at least half-a-year spell in the Russian army;[103] he had served in a cavalry regiment in Odessa before.[104] It is not clear why the prince left the Black Sea coast and what political, diplomatic or military mechanism got him landed in Warsaw;[105] the choice was probably determined by family logistics.[106] Though convenient travelwise, given the role of Warsaw garrison the assignment was a challenge from military perspective, especially that don Jaime was assigned to the Life Guard Grodno Hussar Regiment (Гродненский гусарский лейб-гвардии полк).[107] His new unit was a cavalry regiment[108] forming part of the very prestigious if not somewhat snobbish, Russian aristocracy dominated Life-Guard category.[109]

It is not entirely clear what was Don Jaime's rank when he arrived in Warsaw; Spanish press referred to him as "teniente",[110] Polish press referred to him as "chorąży".[111] There is no official Russian document available for consultation; the most likely rank was "Praporshchik" (прапорщик; equivalent to Ensign).[112] On 17 September 1900 he was formally promoted to the rank of "Poruchik" (поручик; equivalent to Lieutenant)[113] and at that rank he served until the end of his actual Warsaw assignment, though in 1904 he was promoted to the rank of "Kapitan" (капитан; equivalent to Captain)[114] and finally to "Polkovnik" (полковник; equivalent to Colonel). None of the sources consulted provides any information on don Jaime's function in the regiment and it is not known whether he served in regimental staff or with any of the squadrons.[115] In late 1902 the press reported that upon return from a just commencing 6-month leave, the following May don Jaime would intend to seek release from duty,[116] but in late summer 1903 he was still reported serving.[117] In October 1903 he was transferred from the Hussar Regiment to personal staff assigned to the Warsaw district commander.[118]

Duration and sub-periods

Though he was formally appointed to Warsaw in December 1897[119] and though it is likely he spent a few brief spells in the city between 1904 and 1906, there is no confirmation of don Jaime actually serving in Warsaw before March 1898[120] and after October 1903.[121] His duty was largely performed on the on and off basis; in-between the above dates he spent in total some 40 months in the city, on average slightly more than half a year per annum.[122] Except 1898 and 1899 he used to leave around November, as allegedly the local autumn weather did not serve him well;[123] don Jaime was usually returning to service around April.[124] The longest uninterrupted stay identified was between November 1899 and June 1900.[125] Punctuated by at least month-long breaks of leave periods, his service in Warsaw broke down to 8 separate strings.[126]

When away, don Jaime was either on leave in Austria-Hungary, Italy and France[127] or on service assignments with the Russian army: as member of demarcation commission at Russian frontier with Turkey, Afghanistan and Persia (from summer to fall 1899),[128] in combat units during the Boxer Uprising (from summer 1900 till spring 1901)[129] and during the Russo-Japanese War (starting the spring of 1904). He also spent brief rest periods in the Polish countryside.[130] He was last reported in Warsaw in late autumn of 1903,[131] leaving the city some time by the end of the year. As at that time he was already released from the hussar regiment, it is likely he intended to terminate his Warsaw service. During outbreak of the war against Japan in early 1904 Don Jaime was with his father in Venice, where he was reached by the call to arms; before having been received by Nicholas II in St. Petersburg in March he was likely to have stayed few days in Warsaw, though this was not recorded by the local press. It is also possible—though not confirmed in sources—that he spent few days in Warsaw in June 1905 (en route from Austria to St. Petersburg and back) and in July/August 1906 (en route from Paris to St. Petersburg and back)[132]

Private life

Initially Don Jaime lived in a semi-rural, military-dominated Sielce suburb, hardly within the administrative city limits; his residence was a modest one-room apartment in the regimental officers' barracks building at Агриколя Дольная street, with two batmen – one of them Spanish – living next door.[133] Starting June 1900 he was already reported as living at Шопена street 8,[134] in a plushy, prestigious area and in a newly constructed apartment building. Despite his modest rank don Jaime took part in official feasts seated among most prestigious participants, be it members of the House of Romanov, top Russian generals like military district commander or civil officials like president of Warsaw.[135] Very sporadically he was reported as taking part in gatherings of local elites, either those associated with visits of his distant relatives like Ferdinand Duke of Alençon[136] or feasts of apparently unrelated Polish aristocrats like count Mieczysław Woroniecki.[137]

Though possibly familiar with religious hierarchs,[138] in general Don Jaime was not listed as engaged in local community life;[139] he declared spending his free time in theatres and restaurants[140] and indeed was noted there.[141] He was, however, a noticeable city figure as a sportsman; apart from joining the local horse racing society[142] he was particularly recognised for automobile activities.[143] He owned one of the first cars in Warsaw, a De Dion Bouton machine allegedly well recognised by the city dwellers. The only local he seemed to have been in closer relations with was Stanisław Grodzki, a Warsaw automobile pioneer and owner of the first car dealership;[144] local motor fans were greeting Don Jaime when he was launching his automobile trips.[145] Rather accidentally don Jaime was also acknowledged and cheered as a sportsman by "forgemen, peasants and innkeepers".[146] Spanish press reported Carlist officials departing from Madrid to see him,[147] but the Polish one has not noted any visits paid.

Politics

The Warsaw press of the era was fairly well informed about developments in Spain, with war against the United States systematically reported and even results of the Cortes elections discussed down to minuscule details; e. g. in 1899 there were 4 Carlists noted as elected.[148] Spanish political life was depicted rather accurately if not indeed prophetically,[149] though at times with some patronising tones.[150] It was acknowledged—even in jokes—that very few Poles knew who the Carlists were.[151] Despite occasional references to Carlism in news columns, cases of linking these reports with don Jaime residing in Warsaw were rather exceptional.[152] Usually press notes referred to don Jaime as "His Royal Highness", they were maintained in polite style which has never turned into anything more than sympathetic desinteressement.[153] Not a single case of either hostile or friendly stance towards the Carlists has been identified.[154] Though interviews with don Jaime adhered to respectful and warm tone, they by no means amounted to political proselytism;[155] some of them sounded slightly ironic about the Carlist cause.[156]

Historically relations between Russia and Carlism have been marked by indifference with occasional demonstrations of mutual sympathy.[157] Don Jaime has not been noted as involved in any political initiatives, though his taking part in official Russian feasts with members of the House of Romanov participating was clearly flavoured with political undertones. At one opportunity the prince made some effort to court the Poles, referring to alleged Polish combatants in ranks of the legitimist troops during the last Carlist war;[158] official Spanish diplomatic services tried to keep a close watch on him.[159] National and social unrest which erupted in Warsaw in 1905 occurred after don Jaime had already left the city; he had little opportunity to make his own opinion let alone take sides. It is not clear whether vague personal references to the Russian revolution, made by don Jaime in his 23 April 1931 manifesto, were anyhow related to the 1905 events.[160]

Warsaw spell in perspective

Don Jaime joined the Russian army in his mid-20s, in-between youth and mid-age, straightforward, easy-going,[161] just about to get married and to launch his international career.[162] His last, brief Warsaw spells occurred when he was in his mid-30s, a solitary who by some was already viewed as a bit of a disappointment.[163] For the rest of his life he remained a highly ambiguous if not mysterious figure and is as such acknowledged in historiography.[164] It is not clear to what extent service in the Russian army contributed to his formation.[165] Imperial Guards corps officers made a peculiar company, with own identity, values and rituals,[166] especially in an ethnically alien ambience. According to a Polish cliché a cynical lot,[167] their preferred sports were allegedly womanising,[168] drinking and tormenting Jews in the jolly westernmost garrison of the Empire, in Russian officer-speak known as весёлая варшавка.[169] Some of his Carlist opponents claimed that in the early 1900s don Jaime was already ideologically derailed.[170]

Don Jaime is not known to have publicly and explicitly referred to the Warsaw service in the decades to come.[171] In Spanish historiography the Warsaw spell is usually treated marginally.[172] Don Jaime's military career in the Far East is at times acknowledged as sort of a curiosity,[173] though his service in the Russian army is mentioned when discussing controversies within Carlism related to Spain's role in the First World War.[174] Historiographic works on Carlism focus either on don Jaime's role in internal strife in the 1910s or on his very last years during dictablanda and the Second Spanish Republic in the early 1930s.[175] In Polish historiography his hussars spell went largely unnoticed. Dedicated works dealing with Spanish-Polish relations acknowledge even brief Polish episodes of celebrities like Pablo Picasso or Carmen Laforet but they ignore don Jaime,[176] even though along Sofía Casanova (1907–1945) and Ignacio Hidalgo de Cisneros (1950–1962) he is one of the best-known Spaniards permanently residing in Warsaw.[177]

Claimant to the Spanish and French thrones

On 18 July 1909 Jaime succeeded his father as Carlist claimant to the throne of Spain and Legitimist claimant to the throne of France. As Carlist claimant to Spain he was known as Jaime III, but used the style Duke of Madrid. As Legitimist claimant to France he was known as Jacques I, but used the style Duke of Anjou.

Jaime retired from the Russian army and henceforward lived mostly at Schloss Frohsdorf in Lanzenkirchen in Austria and at his apartment on Avenue Hoche in Paris. He visited Spain incognito on a number of occasions.[178] He also owned the Villa dei Borbone at Tenuta Reale near Viareggio in Italy which he had inherited from his mother.[179]

.jpg)

For part of World War I Jaime lived under house-arrest at Schloss Frohsdorf in Austria.

On 16 April 1923, by a decree to his Delegate-General in Spain, the Marques de Villores, Jaime created the Order of Prohibited Legitimacy (Orden de la Legitimidad Proscrita) to honour those who suffered imprisonment in Spain or were exiled for their loyalty to the Carlist cause.

In April 1931 the constitutional king of Spain Alfonso XIII was forced to leave the country and the Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed. Jaime issued a manifesto calling upon all monarchists to rally to the legitimist cause.[180] Several months later, on 23 September, Jaime received Alfonso at his apartment in Paris.[181] Two days later Alfonso and his wife Ena received Jaime at the Hotel Savoy d'Avon near Fontainebleau.[182] Jaime conferred the collar of the Order of the Holy Spirit upon Alfonso. These meetings marked a certain rapprochement between the two claimants to the Spanish throne. According to some authors – contested by the others – the two signed or verbally agreed an arrangement which would terminate the Alfonsist-Carlist discord.

A week after his meetings with Alfonso, Jaime died in Paris. He was buried at the Villa dei Borbone at Tenuta Reale. He was succeeded in his Spanish and French claims by his uncle Alfonso Carlos, Duke of San Jaime.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Jaime, Duke of Madrid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Enumerated after Jaime II, King of Aragon.

- in 1911 his former cook sued Don Jaime over fatherhood of her son; the case was dropped in unclear circumstances, El Pais 03.11.12, available here, Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El caso Feliú y el dominio de Mella en el partido carlista en el período 1909–1912, [in:] Historia contemporánea 10 (1997), p. 113.

- along the paternal line

- along the maternal line

- along strictly paternal line and 7 generations back his ancestor was the so-called Grand Dauphin Louis de Bourbon. His maternal grandmother was also a granddaughter of Charles X, the king of France (1824–1830)

- the maternal grandfather of his maternal grandmother was Francis I of Borbón-Two Sicilies

- the mother of his paternal grandfather was María Francisca de Bragança

- the maternal grandmother of his maternal grandmother was archduchess María Clementina Habsburg-Lothringen

- the paternal grandmother was archduchess María Teresa de Austria-Este

- the mother of his maternal grandfather was Maria Teresa di Savoia

- along strictly paternal line and 33 generations back his ancestor could be traced to the 8th century

- for details, see the ancestry chart below

- B. de Artagan [Reynaldo Brea], Príncipe heróico y soldados leales, Barcelona 1912, p. 13

- two pairs of his uncles and aunts had no children: it was the case of his paternal uncle Alfonso Carlos with his wife and this of his maternal uncle prince Henry, count of Bardi with his two wives. His another maternal uncle Robert Bourbon-Parme with his two wives had 24 children (one stillborn), while his maternal aunt and her husband Ferdinand Habsburg-Lothringen had 10 children

- prince Louis Borubon-Parme (1899–1964) in 1939 married princess Maria Francesca of Savoy, the youngest daughter to the king of Italy; after the war the couple settled in France. They had 4 children

- prince René Bourbon-Parme (1894–1962) in 1921 married princess Margaret of Denmark, where he settled and had 4 children

- archduchess Louise Habsburg (1870–1947) in 1891 she married the crown prince of Saxony and became the Saxon queen-in-waiting. However, due to poor relations with her in-laws and her husband she fled in 1902. With various partners she lived in France, England, Switzerland, Italy and finally Belgium, where she died in poverty

- cases of Elié, Sixte, Xavier, Zita, Felix, René, Louis and Gaetan

- archduke Leopold Habsburg fell in love with a prostitute, renounced his titles and married the woman in 1902; two other marriages followed. Archduchess Louise Habsburg fled her husband, the crown prince of Saxony, and with various partners for decades lived in France, England, Switzerland and Belgium. Archduke Heinrich Habsburg had a love affair with a commoner and children with another one, married in 1919. Archduke Joseph Habsburg also fell in love with a commoner, to renounce his titles and marry her in 1921

- Leopold Salvator died in 1931. The widowed Blanca lived mostly in Spain and Italy, while some of her sons claimed Carlist heritage rights and posed as kings of Spain from the 1940s onwards

- Francisco Melgar, Veinte años con Don Carlos. Memorias de su secretario, Madrid 1940, pp. 103–104. When asked by Leopold Ferdinand why he permitted earlier Habsburg marriage with Doña Blanca, the kaiser allegedly responded "that was an error", see José María Zavala, Bastardos y Borbones: Los hijos desconocidos de la dinastía, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788401389924, especially the chapter Amores fatales

- Manuel Polo y Peyrolón, D. Carlos de Borbón y de Austria-Este, Valencia 1909, p. 54

- detailed account in Zavala 2011

- La Correspondencia Militar 10.11.29, available here

- La Epoca 05.02.02, available here

- Melgar 1940, p. 213

- Melgar 1940, pp. 213–214. The name is also spelled as "Del Prette" or "Delprete"

- the Spanish repeatedly and consistently claimed that two well-known Italian aviators, one of them among the first pioneers who crossed the Atlantic, were grandchildren of the Carlist king, see e.g. El Sol 07.07.28, available here, or La LIbertad 17.08.28, available here. The same opinion in Zavala 2011, see the chapter Los Aviadores. Contemorary Italian authors claim his parents were Lorenzo del Prete and Fedilla Francini, see e.g. Del Prete, Carlo entry, [in:] Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani online, available here

- María de las Mercedes Borbón y Austria (1880–1904) married prince Carlos of Bourbon-Two Sicilies in 1901

- allegedly the plan was created by the Vatican in collaboration with the imperial court in Vienna. For 1886 rumors on Maria's marriage with Don Jaime see e.g. El Siglo Futuro 19.05.86, available here. The rumors persisted and were repeated for years to come, for 1888 see e.g. La Lucha 25.07.88, available here, for 1889 see La Lucha 22.12.89, available here

- Mathilde of Bavaria (1877–1906) married Prince Ludwig of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1900

- exact reasons for Bertha de Rohan's opposition to the marriage are not clear; some authors accused her of pure feminine jealousy and ill will. When talking to her husband, Doña Bertha allegedly charged Mathilde with misconduct, Melgar 1940, p. 159

- it is not clear what exactly was the nature of Don Jaime's epistolographic relationship with princess Mathilde, yet both Prince Ludwig and Don Carlos understood the matter was serious. Prince Ludwig might not have been averse towards a would-be marriage, yet his wife Maria Theresa maintained friendly relationship with the court in Madrid and was reportedly opposed to her daughter marrying a Carlist prince, Melgar 1940, p. 161

- one press note quoted don Jaime declaring himself admirer of handsome Warsaw ladies, see Tygodnik Ilustrowany 21.05.98, available here, though the thread was not followed further on

- Marie-Antoinette de Borbón-Parma (1895–1977) has never married and died as a Benedictine nun. She has caught Don Jaime's attention during family meetings due to her reported beauty, youth and charm. At that time she was only 16 years old and "casi una niña"; the affection was probably never revealed, yet it seems that Don Jaime was seriously pondering upon a would-be relationship, since he decided to discuss it with his secretary. Don Jaime's secretary reportedly tried to persuade his king the impracticability of such a union, Roman Oyarzun Oyarzun, Pretendientes al trono de España, Barcelona 1965, p. 84

- allegedly Don Jaime pursued Zita zealously and stubbornly, though the source of this information, Elvira de Borbón, is of questioned credibility, España 16.09.22, available here. Zita wrote later that "qui avant demande ma main avec autant de zele que d’insucces", Jacques Bernot, Les Princes Cachés, Paris 2014, ISBN 9782851577450, p. 131

- Zita de Bourbon-Parma (1892–1989) married archduke Karl in 1911; the groom was second-in-line heir to the Austrian and Hungarian thrones

- Melgar 1940, p. 168

- Bernot 2014, p. 131

- Patricia Connaught (1886–1974) was daughter to Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, a member of the royal British family; she married with relatively low-rank English aristocrat in 1919. For news on her marriage with Don Jaime see L’Univers 20.03.14, available here

- e.g. in August 1910 the press announced Don Jaime's near marriage with an unnamed "niece of the German kaiser" or "a German princess", see Le Gaulouis 14.11.10, available here. The oldest niece of Wilhem II which was not married at the time was princess Helen of Greece, aged 14

- El Pais 03.11.12, available here, Andrés Martín 1997, p. 113. Don Jaime has admitted to maintaining "intimate relations" with his female cook and seemed even prepared to accept the child as his natural one, but he noted that the woman had maintained relations also with a servant and a Russian colonel, so fatherhood was not clear. The Russian colonel interviewed as a witness refused to give evidence and the case was dropped. The cook pledged she would keep demanding justice from Don Jaime, but the press did not note any follow up

- Fabiola Massimo (1900–1983), daughter to Don Jaime's younger sister Beatriz, married an Italian aristocrat in 1922

- Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español, vol. 29, Seville 1960, p. 140

- España 16.09.22, available here

- La Acción 03.07.23, available here

- Blanca de Borbón y León (1898–1989) was daughter of Francisco de Paula de Borbón y Castellví, himself son of Enrique, Duke of Seville; she married conde de Romanones in 1929. For the news of her would-be marriage with Don Jaime see Le Petit Parisien 07.10.24, available here

- Filipa de Bragança (1905–1990) was daughter to Miguel II de Bragança, legitimist claimant to the Portuguese throne; she has never married. For news on heir would-be marriage with Don Jaime see Heraldo de Madrid 02.01.28, available here

- e.g. upon news of nearing marriage with Filipa de Bragança political secretariat of Don Jaime issued an ambiguous statement; on the one hand it declared the news incorrect, on the other it referred to the information as "premature for now", La Epoca 05.01.28, available here. Don Jaime used to entertain Filipa and her mother in his Frohsdorf castle during a few weekly strings

- which does not mean that Don Jaime was equally disposed towards all these nations. He considered himself a Spaniard and harbored very strong Francophone sympathies; he also admired the British. In his youth perfectly familiar with the German realm, during the Great War he developed adverse feelings towards especially the Austrians. Don Jaime in his youth consistently denigrated the Italians, his later views are not clear

- B. de Artagan [Reginaldo Brea], Príncipe heróico y soldados leales, Barcelona 1912, pp. 13–14

- Bernardo Rodríguez Caparrini, Alumnos españoles en el interado jesuita de Beaumont (Old Windsor, Inglaterra), 1888-1886, [in:] Hispania Sacra 66 (2014), p. 412

- Brea 1912, p. 15

- until late summer 1876 Margarita and her children stayed in Pau, Jordi Canal, Incómoda presencia: el exilio de don Carlos en París, [in:] Fernando Martínez López, Jordi Canal i Morell, Encarnación Lemus López (eds.), París, ciudad de acogida: el exilio español durante los siglos XIX y XX, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788492820122, p. 92

- the preceptors included elderly Carlist general León Martínez de Fortún and a young Navarrese priest, Manuel Fernández de Barrena. At later stage they were replaced with Miguel de Ortigosa

- the building does not exist any more. It was demolished upon construction of Rue de Siam

- Don Carlos he returned to Paris in September 1876 and left for the Balkans in December 1876, Canal 2010, pp. 92–93

- Beatriz Marcotegui Barber, Olaia Nagore Santos, Visit to the Temporary Exhibition at the Museum of Carlism [internal booklet issued by Museum of Carlism], Estella 2012, p. 19

- Melgar 1940, p. 38. According to other sources Carlos VII was expulsed in 1881 and settled in Venice in 1882, Canal 2010, p. 112

- doña Margarita has freshly inherited the Tenuta Reale property from her grandmother, Melgar 1949, p. 47

- Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 412

- total outlay on 5-year education at Beaumont was in the region of £600; average income of a small farming household was around £38. A contemporary scholar notes that the expense involved "effectively ruled out all but the wealthiest Catholic families", Oliver P. Rafferty, Irish Catholic Identities, Oxford 2015, ISBN 9780719097317, pp. 265–266

- about 20% of boys were Irish, The boy who would later turn into another recognizable public figure was Patrick O’Byrne (born 1870), son to an Irish landowner and future anti-Treaty Sinn Féin revolutionary, Rafferty 2015, pp. 266–267. Percy O’Reilly (1870) was a silver medallist for polo at 1908 Olympics. Apart from Don Jaime, there were few more Spaniards in the college

- father Hayes, born 1839, was slightly older than Fernández de Barrena, born in the mid-1840s

- Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 414

- the only boy who could have competed with Don Jaime in terms of status was son of the prime minister of South Africa, Thomas Upington (born 1872), Rafferty 2015, pp. 266–267

- Don Jaime taught his colleagues to smoke cigarillos; when detected, other boys were slammed, but Jaime was not, Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 415

- e.g. in 1882 Don Jaime was visited by parents and all 4 sisters to assist in his first communion, Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 420

- Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 417

- e.g. in 1882 in Venice, Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 422

- e.g. once he declared "when I am a king, I will make you Juan a governor, and you Roberto will be a minister", Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 423

- e.g. when practicing boxing, Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 428

- Rodriguez Caparrini 2014, p. 442

- La Epoca 26.07.96, available here

- contemporary press mentioned gastric issues, see La Correspondencia de España 21.10.86, available here, contemporay scholars talk about typhus, Marcotegui Barber, Nagore Santos 2012, p. 25

- El Liberal 17.03.87, available here

- Brea 1912, p. 20

- there were speculations that the Nocedalistas might declare Carlos VII deposed and offer the Carlist crown to Don Jaime, La Justicia 16.07.88, available here, or that Carlos VII might seek compromise with the Nocedalistas by abdicating in favor of Don Jaime, El Tradicionalista 07.08.88, available here

- El Bien Público 09.10.88, available here a

- La Epoca 18.08.88, available here

- the years of 1890–1892 are the period when his mother developed particular concerns about Don Jaime, considered not only childish but also impulsive, non-systematic, interested mostly in horses and plays, in general – a person who needed close tutelage and supervision. For details, see correspondence between Margarita de Borbón and the Ortigosas, in Francisco Javier Caspistegui (ed.), Carlos VII. Cartas familiares. Estudio preliminar y edición, Pamplona 2016, ISBN 9788494462504

- populated by "ateos y escépticos y corrompidos", Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista. Historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820, pp. 42–44

- Andrés Martín 2000, pp. 42–44 and onwards

- according to one author he graduated with "más alta de la promoción" position, Ferrer 1960, p. 11

- the Austrian kaiser was particularly cautious about the Carlist pretenders since in 1879 his relative Maria Christina married the Alfonsist pretender styled as king Alfonso XII. However, the emperor maintained cool yet still correct relations with the Carlist claimant. As head of the House of Habsburg he permitted the 1889 marriage of archduke Leopold Ferdinand with Don Carlos’ daughter, the decision he later declared to have been an error. When in 1893 Don Carlos formally approached him re his own planned marriage with Berthe de Rohan, the Austrian citizen, the kaiser consented but explicitly demanded that the Carlist claimant stops tampering with the Spanish affairs. Carlos VII immediately rejected the demand, which caused almost total breakdown of relations between the two, Melgar 1940, pp. 96–98, see also Ferrer 1960, p. 11

- Polo y Peyrolón 1909, p. 24

- some sources claim that Don Jaime was in Spain in 1882, Marcotegui Barber, Nagore Santos 2012, p. 20

- La Epoca 09.07.09, available here

- the friendly anecdote featured a train conductor en route to Burgos declaring himself a former Carlist cavalryman, Actualidades 1894, available here; the unfriendly one featured a comment allegedly heard from a passer-by: “oh, so this is Don Jaime? incredible, so young and already the son of Carlos VII!”, El Dia 04.10.94, available here

- Jordi Canal i Morell, La revitalización política del carlismo a finales del siglo XIX: los viajes de propaganda del Marqués de Cerralbo, [in:] Studia Zamorensia 3 (1996), pp. 269–70

- it is unlikely that France, an icon of republicanism, has ever been considered. The Italian army was most likely out of the question due to the conflict with Vatican and deposition of Parma, Modena and Tuscany dukes, all related to the Borbon family. Besides, the Italian army might not have been considered prestigious enough

- Polo y Peyrolón 1909, p. 79

- he was first reported to join the 24. dragoon's regiment in February, La Dinastia 20.02.86, available here, but in late March the press reported he would join his unit upon mastering the basics of Russian (and ridiculed that mastering castellano might be more difficult), see La Justicia 30.03.96, available here. In early July Don Jaime was already noted as serving in Odessa, La Ilustracion Española y Americana 8 July 1896, available here

- In 1900, Madrid had 575,000 and Barcelona 539,000 inhabitants. La población en España: 1900–2009. Cuadernos Fundación BBVA, p. 5, available here. The population of 1899 was 646,000 (excluding the military), Kurjer Warszawski 05. 05.1899, available here

- see demoscope.ru service offered by Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета "Высшая школа экономики", available here. Somewhat different data, with breakup not by nationality but by faith, in Kurjer Warszawski 05.05.99

- In English-language historiography the unit is referred to as "Vistula Land", a direct translation from Russian. For informative snapshot of administrative transformations of Polish territories in the 19th and 20th centuries, see Norman Davies, God's Playground. A History of Poland, vol. 2, Oxford 2005, ISBN 9780199253401, p. 6

- It was one of the most industrialized regions of Russia. In the early 1890s it provided 16% of Russian iron/steel production, 20% of cotton and 38% of coal, Józef Buszko, Historia Polski 1864–1948, Warszawa 1979, ISBN 8301001720, p. 122

- Buszko 1979, p. 100; for overview of Polish nation-building and the Polish cause in late 20th century under the Russian rule see Davies 2005, especially the chapter Rossiya: The Russian Partition, pp. 60–82

- Warsaw hosted a few infantry and cavalry regiments. At the time of Jaime's arrival, the top military official was commander of the Warsaw military district, general Александр Константинович Имеретинский (Kurjer Warszawski 02.05.99); the second in function was commander of the Warsaw garrison, general Пётр Дмитриевич Паренсов (Kurjer Warszawski 24.04.99); titular commander of don Jaime's regiment was Grand Duke Павел Александрович (Kurjer Warszawski 28.02.99), but there were really other generals commanding. Also, the top officials assuming civil posts were military; the president of the city was a general Николай Валерианович Бибиков (Kurjer Warszawski 13.05.99)

- the Russo-German political accord, which ensured stability in Eastern Europe across most of the 19th century, started to crack at the Berlin Congress. The military alliance between the two empires was being renewed though scaled down across the 1880s; eventually, the so-called Reinsurance Treaty was not extended in 1890. In 1892, Russia and France signed a military convention aimed against Germany, the first step towards the system of alliances in place during the First World War, Roderick R. McLean, Royalty and Diplomacy in Europe, 1890–1914, Cambridge 2007, ISBN 9780521038195, pp. 18–20, George Frost Kennan, The Fateful Alliance: France, Russia, and the Coming of the First World War, Manchester 1984, ISBN 9780719017070, pp. 18–36

- overview of the Miliutin-Obruchev system in Richard F. Hamilton, Holger H. Herwig, War Planning 1914, Cambridge 2010, ISBN 9780521110969, pp. 88–104

- Hamilton, Herwig 2010, p. 86

- according to some Spanish sources don Jaime's service in Odessa lasted 6 months, Salvador Bofarull, Un príncipe español en la Guerra Ruso-Japonesa 1904–1905, [in:] Revista de Filatelia 2006, p. 55, accessible here. However, the dates hardly match. Some authors claim he was received by the tsar Nicholas II "early 1896" and immediately followed to his Odessa unit, Artagan 1912, p. 24. In March 1897 he was reported sporting a Russian uniform when visiting France, Kurjer Warszawski 23.02.97, available here. He received transfer order in December 1897 and left Odessa probably in January 1898, Artagan 1912, p. 24, El Correo Militar 30.12.87, available here

- Spanish sources usually refer to "24. Regimiento de Dragones de Loubna" (transliterated into Latin alphabet with different degree of accuracy; Лубна is a river, tributary of the Don, and flows across a traditional cossack area), compare Artagan 1912, p. 24. Other sources claim that the official name was "8th His Imperial Highness Archduke Otto of Austria's Lubny Hussar Regiment"; its headquarters was in Odessa and it formed part of the 8th Cavalry Division, stationed in Kishiniev, compare marksrussianmilitaryhistory service, available here. There is a source which acknowledges the difference and attempts to clarify the confusion as to numbering and as to dragoon v. hussar issue, see Михаил Быков, Офицерской национальности, [in:] Русский мир 08.13, available here. The author claims that 8-м Лубенский гусарский полк was renamed to 24-й Лубенский драгунский полк during the reign of Alexander III, and that the reverse process was commenced in 1907

- Polish press of the era claimed Don Jaime was transferred to Warsaw on his own request, Tygodnik Ilustrowany 21.05.98, available here, Kurjer Warszawski 30.04.98, available here

- in 1886 Don Jaime inherited from late archduchess Maria Theresa of Austria-Este (sister of his paternal grandmother, who died with no issue) the castle of Frohsdorf, located 50 km away from Vienna. As he was only 16 at the time, his father was allowed usufruct of the residence, compare Schloß Frohsdorf und seine Geschichte service, available here, Agustín Fernández Escudero, El marqués de Cerralbo (1845–1922): biografía politica [PhD thesis], Madrid 2012, p. 425. At that time Warsaw and Vienna were connected by regular and fast railway service, for timetable compare Gazeta Handlowa 04.05.86, available here (Warsaw to Austrian border) and here (Russian border to Vienna). Don Jaime's father visited Warsaw before the Third Carlist War and liked the city, at least according to the confession made to a Pole visiting him in Estella, Ignacy Skrochowski, Wycieczka do obozu Don Karlosa, [in:] Piotr Sawicki (ed.), Hiszpania malowniczo-historyczna, Wrocław 1996, ISBN 8322912153, p. 170. He visited the city another time on 9 February 1877, Kurjer Warszawski 10.02.77, available here

- for detailed history of the unit see Юлий Лукьянович Елец, История Лейб-Гвардии Гродненского Гусарского полка, New York 2015, ISBN 9785519406048. Though named after the city of Grodno, the regiment has never been stationed there

- none of the sources consulted provides information whether the cavalry career was in line with military training Don Jaime had received earlier in Wiener Neustadt

- in the Russian army of the era there were only 2 Hussar Life-Guard regiments, apart from the Grodno one also the personal Tsar Regiment, see regiment.ru service, available here

- El Correo Militar 30.12.97, available here

- Kurjer Warszawski 24.11.98, available here

- literally translatable as Polish "chorąży", English "standard-bearer" or Spanish "abanderado"; in some armies the rank corresponded to the first officer rank and in some to a rank in-between NCOs and commissioned officers. Other options possible are that Don Jaime's rank was подпоручик or корнет

- Kurjer Warszawski 26.9.00, available here

- during the Russo-Japanese War, on 7 May 1904, Bofarull 2006, p. 56. Don Jaime was still captain when in 1906 the tsar asked him to stay in service, La Epoca 13.07.06, available here

- though given his limited (if any) knowledge of Russian it is hard to imagine how he could have served in line and communicated with NCOs and soldiers

- Kurjer Warszawski 24.10.02, available here

- Kurjer Warszawski 17.09.03, available here

- Kurjer Warszawski 25.10.03, available here

- Artagan 1912, p. 24, El Correo Militar 30.12.87, available here

- the first confirmed press note is Kurjer Warszawski 30.04.98

- the last confirmed note of Don Jaime serving was provided by Gazeta Kaliska 18.09.03 (October Spanish calendar), available here. There is a single case of a Warsaw paper issued after 1903 and referring to Don Jaime as "lieutenant of the hussar regiment, stationed in our city", see Nowa Gazeta 21.07.09, available here. The note, however, was acknowledging death of Carlos VII and seems based on some outdated editorial materials; it contains many factual errors (e.g. that Carlos VII returned to Spain in 1878 and that don Jaime was wounded in Russo-Japanese war in 1900)

- approximately 6 months in 1898, 8 months in 1899, 7 months in 1900, 7 months in 1901, 6 months in 1902 and 6 months in 1903

- "że mu zupełnie nie służy jesień klimatu polskiego", Kurjer Warszawski 12.11.98, available here

- as was the case in 1900, 1901 and 1902

- in November 1899 he was reported in Skierniewice, see Kurjer Warszawski 03.11.98, available here, and in June 1900 he was reported leaving Warsaw for Paris, Kurjer Warszawski 10.06.00, available here

- 1) late winter 1898 till summer 1898 (followed by summer in unspecified location), 2) August 1898 till November 1898 (followed by around 4 weeks on leave in Austria), 3) December 1898 till summer 1899 (followed by demarcation work at borders with Turkey, Afghanistan and Persia), 4) unspecified time late 1899 or early 1900 till June 1900 (followed by a month in Paris), 5) July till August 1900 (followed by Boxer War campaign), 6) spring 1901 till late 1901 (followed by stay in Paris and Nice), 7) spring 1902 till October 1902 (followed by stay in Paris and Nice), 8) spring 1903 till autumn 1903 (followed by stay in Venice, and then departure to the Russo-Japanese war)

- he underwent tracheotomy in Nice following a car accident there in January 1902, Kurjer Warszawski 02.01.02, available here

- Artagan 1912, p. 24; in October 1899 he was already reported back in Warsaw

- Gazeta Lwowska 08.08.00, available here

- Kurjer Warszawski 17.07.01, available here

- Gazeta Kaliska 18.09.03

- trips were alleged by the Spanish press though none of the local Warsaw papaers confirmed don Jaime's stay, compare e.g. Gazeta Kaliska 15.03.04, Czas 05.03.04, Kurjer Warszawski 13.04.04

- "all apartment is one room, with 2 windows covered by white cotton curtains embroidered in Scottish patterns..." and onwards with the same detailed focus. Grand portrait of Don Carlos was noted on the wall. Kurjer Warszawski 18.04.98, available here

- Kurjer Warszawski 10.06.00; the building was damaged during the Warsaw Uprising but still fairly well preserved in early 1945, compare here; it was probably demolished in the late 1940s, see here

- Kurjer Warszawski 15.11.99, Wiek 16.09.01, Gazeta Kaliska 18.09.03

- Kurjer Warszawski 30.08.01, available here

- in the summer of 1901 don Jaime was in Kanie, a real estate near Lublin, taking part in engagement of Elżbieta Woroniecka, daughter of duke Mieczysław Woroniecki, with Paweł Jurjewicz, Kurjer Warszawski 17.07.01

- in 1910–1911 in Frohsdorf Don Jaime was visited by "el rector de una orden religiosa de Varsovia", who pressed the marriage question, Roman Oyarzun, Pretendientes al trono de Espana, Barcelona 1965, p. 83

- e.g. attending charity balls, Catholic feasts or cultural events. One press note quoted don Jaime declaring himself admirer of handsome Warsaw ladies, see Tygodnik Ilustrowany 21.05.98, available here, though the thread was not followed further on

- Kurjer Warszawski 18.04.98

- for feminine view of Don Jaime as met in the opera see Clycére Emilie de Witkowska, Don Jaime, en el Régimiento de Húsares de Grodno, [in:] Tradición II/41 (1934), pp. 408–410

- Tygodnik Ilustrowany 21.05.98, available here

- the Warsaw papers provided picturesque and detailed accounts of don Jaime's departure for Paris, see Kurjer Warszawski 23.06.00, available here, also here. After 10 days he was confirmed arriving in Paris, El Correo Militar 02.07.00, available here

- don Jaime repeated the pioneering journey of Grodzki from Warsaw to Paris, compare Początki polskiej motoryzacji [in:] motokiller service, available here

- Kurjer Warszawski 10.06.00, available here

- Kurjer Warszawski 10.06.00

- de Cerralbo was reported departing for Warsaw, see La Correspondencia de España 29.9.01, available here

- Kurjer Warszwski 21.4.99

- "Carlists and Republicans form two extreme wings, both hostile to the existing regime. Conservatives and Liberals form two wings of mainstream politics, competing for offices, perks and privileges; in terms of program the former are closer to the Carlists, while the latter are closer to the Republicans. [...] A phrase making rounds is that only revolution can save the country, but neither a Carlist nor a far more probable Republican one can change anything; power will move to another bunch of politicians, very much like the currently ruling cliques. Worse, a Republican revolution will undoubtedly trigger a civil war, and victory of the Republicans will produce a Carlist rising, and a Carlist rising will bring about the claims of independence from Catalonia and Navarre", Wojciech hr. Dzieduszycki, Wrażenia z Hiszpanii, [in:] Biesiada Literacka 05.07.01, available here

- "telegraph wires seem to be on the poles, but do not be so naive to attempt sending a telegraph message beyond Spain; even the diplomatic ones get lost somewhere on their way. Roads exist only in theory. Only the schools maintained by bishops do function, state-ran secondary schools are rather like primary ones. The army looks nice, but when it came to war they had neither food nor munitions", Biesiada Literacka 05.07.01. However, an average 1900 Polish GDP per capita is estimated (in Geary-Khamis dollars) at 86% of the corresponding Spanish figure, compare here

- "At a patisserie: who are those Carlists, who make fuss in Spain? [apparently a Pole asking a Jew]; I do not know, but I guess they must be sort of Spanish Jews; what makes you think so, Moshe? [in street-talk a name commonly standing for a traditional Jew, friendly though very patronising way of addressing]; well, I am not sure, but they write here in the paper that 10,000 rifles were taken away from the Carlists when having been smuggled from France to Spain". The joke probably requires a lengthy footnote to get all undertones explained; in a veiled way it referred to harassment of the Jews (either official Russian or popular Polish one), their economic focus on trade, often semi-legal nature of Jewish business and Polish perception that according to the Jews the world revolved around them. It also delivers clear sense of total ignorance, desinteressement and lack of emotional engagement as to Carlism if not indeed the entire Spanish politics. Mucha 07.01.00, available here

- reporting that Carlist underground arms depot had been unearthed in Catalonia one paper explained the Carlist cause adding that a descendant of Carlos VII served in Warsaw as a sub-colonel, Zorza 12.11.02, available here

- reporting don Jaime's career during the Boxer Uprising was a tricky exercise; on the one hand, the press followed official course of hailing the Russian army, on the other, venerating articles were incompatible with feelings of those Poles who did not identify themselves with the Russian cause, compare Kurjer Warszawski 12.08.01

- the Polish public opinion of mid-19th century tended to be adverse towards Carlism. The movement was associated with reactionary politics and with Holy Alliance, pitted against the independence of Poland; it was rather revolutionary, liberal forces which were believed to have been sympathetic towards the Polish cause (not necessarily representative and rather extreme example is Wiktor Heltman, Rewolucyjne żywioły w Hiszpanii, ich walka do 1833 roku, [in:] Pismo Towarzystwa Demokratycznego Polskiego 2 (1840), pp. 471–499, presenting Carlism as obscurantism, absolutism and religious fanaticism, compare here, pp. 471 and onwards). Indeed in Spain it generated some compassion mostly among the Liberals, and the term "Poland of the South" was even coined by Emilio Castelar to denote Spain as endangered by oppressive foreign reaction. The Carlists did not demonstrate interest in Polish cause, especially that "polacos" and "polaquería" started to denote anarchy of the First Republic. On the other hand, periodical Carlist onslaught on Bismarck, lambasted for pursuing anti-Catholic Kulturkampf policy, coincided (sometimes explicitly) with Polish feelings. By the end of 19th century Polish references ceased to aid those fearing partitions of Spain and started to help those seeking exactly the opposite. Parallels drawn by nationalistically-minded Basques and Catalans ("Quedo ahora plenamente convencido de que no es Vd. español, sino bizcaino. Los polacos nunca se dirán rusos o alemanes, sino polacos") have certainly not helped the Polish cause among the Carlists. It is not clear to what extent don Jaime, living beyond Spain, was familiar with the above subtleties. Interesting studies on mutual perception in Jan Kieniewicz (ed.), Studia polsko-hiszpańskie. Wiek XIX, Warszawa 2002, ISBN 8391252582, especially the essays of Patrycja Jakóbczyk-Adamczyk and Juan Fernández Mayoralas-Palomegué; enhanced version of the latter's work is available here.

- Don Jaime was presented as "typical son of the South" with detailed description of his physis (Warsaw papers did not print photographs or graphics at that time); introduction was concluded by remark that the prince "makes a nice impression of a mondain", Kurjer Warszawski 30.4.89, available here; also another periodical picked up the same thread (not indifferent in relation to don Jaime's outlook), when quoting that the prince liked Warsaw for its "European character" (and not, e.g., for its Catholic zeal), Tygodnik Ilustrowany 09.05.98, available here

- "so the young prince keeps dreaming about future battles his father will fight to defend his dynastic rights, keeps recollecting heroic Poles who under the standard of Don Carlos stood for the alien cause, and keeps waiting... and waiting...", Tygodnik Ilustrowany 09.05.98

- Russia tended to ambiguity when facing the Carlist question. During the First Carlist War the tsarist administration was somewhat favorable to the cause of Don Carlos but eventually it adopted a wait-and-see policy, even though the Carlist envoy was received in St. Petersburg and the Carlists were aided financially, see José Ramón de Urquijo y Goitia, El carlismo y Rusia, [in:] Hispania. Revista Española de Historia 48 (1988), pp. 599–623. During the Third Carlist War the Russian policy largely followed the course set by Bismarck, anxious that a Carlist victory might sustain French legitimism and internal opposition of the German Catholics, see Joaquim Veríssimo Serrão, Alfonso Bullón de Mendoza, La contrarrevolución legitimista, 1688–1876, Madrid 1995, ISBN 9788489365155, pp. 236–237. At one point Russia has even favored a formally international intervention, to be carried out by the French, to crush the Carlists, Javier Rubio, La política exterior de Cánovas del Castillo: una profunda revisión, [in:] Studia historica. Historia contemporánea 13–16 (1995–1996), pp. 177–187. As to the Carlists, they tended to sympathise with the tsarist regime; the Russian political model was pitted against masonic, liberal and plutocratic French and especially British models, compare the 1905 comments of key Carlist theorist Gil Robles, El Imparcial 07.03.05, available here. Sympathies for the Russian legitimist cause were sustained by a number of White Russians joining Carlist tercios during the Spanish Civil War and this stance is well alive until today, compare 2014 comments of Don Sixto, who called to "reconocer a Rusia sus fronteras históricas", see Monde & Vie 09.04.14, available here

- allegedly he remembered the Polish Carlist volunteers very well, Kurjer Warszawski 30.04.89. This appears to be pure courtesy; first, during the last Carlist war Don Jaime was just a 5-year-old; second, there are very few Poles known to have joined the Carlist troops in the 1870s. In general, the Poles tended to fight against the Carlists rather than to support them. For the First Carlist War see Michał Kudła, Szlak bojowy polskich ułanów w czasie pierwszej wojny karlistowskiej, [in:] Jan Kieniewicz (ed.), Studia polsko-hiszpańskie. Wiek XIX, Warszawa 2002, ISBN 8391252582, pp. 127–161. No Polish unit fought in the Third Carlist War, though some individuals—most notable of them Józef Korzeniowski, known as Joseph Conrad—could have been involved on the Carlist side, for historiographical account see Franciszek Ziejka, Conrad's Marseilles, [in:] Yearbook of Conrad Studies 7 (2012), pp. 51–67, available here. Few thousand volunteers from Poland—though 45% of them were Polish Jews rather than ethnic Poles—joined International Brigades during the Spanish Civil War, Magdalena Siek (ed.), Wojna domowa w Hiszpanii 1941–1987, Warszawa 2010, p. 2, available here

- Eduardo González Calleja, La razón de la fuerza: orden público, subversión y violencia política en la España de la Restauración (1875–1917), Madrid 1998, ISBN 9788400077785, p. 198, Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 400

- "Desgraciadamente mi experiencia política y los largos años pasados en Rusia, me han enseñado que una República patriótica, moderada, bien intencionada puede muy fácilmente y en un espacio de tiempo brevísimo, ser arrollada por la avalancha del comunismo internacionalista, destructor de la religión, de la patria, de la familia y de la propiedad", quoted after José Carlos Clemente Muñoz, El carlismo en el novecientos español (1876–1936), Madrid 1999, ISBN 84-8374-153-9, p. 116

- compare account of his trip to Spain of 1894, published in Tirso de Olazábal, Don Jaime en España, Bilbao 1895. The voyage was also widely reported by the Spanish press, compare La Epoca 09.07.94, available here, El Liberal 10.07.94, available here. The event turned into a media scoop, discussed for months and accompanied by rather friendly anecdotes, compare Actualidades 1894, available here or El Dia 04.10.94, available here

- compare an opinion published in a specialized American review: "his [Carlos VII’s] son, Don Jaime, is serving in a Russian regiment at Warsaw, and has won golden opinions in Russia… a boy scarce out of his teens, whose knowledge of men and things has yet to be acquired, and whose military training is still in the preliminary stages… it is quite possible that the advent [to the throne] of Don Jaime would meet with the approval of Nicholas II… marriage of Don Jaime […] with a reigning Latin family, such as that of Austria, or even Italy, might make a difference on the political chessboard…", James Roche, The Outlook for Carlism, [in:] The North American Review 168/511 (1899), pp. 739–748

- following press reports of don Jaime making statements incompatible with the Carlist ideario, in 1905 his father and at that time the claimant to the throne Carlos VII declared those news unfounded and incorrect; among some Carlists the doubts persisted. Juan Ramón de Andrés Martín, El cisma mellista. Historia de una ambición política, Madrid 2000, ISBN 9788487863820, p. 42

- there are fundamental questions lingering which pertain to his general outlook and to his vision of Carlism, let alone questions about his political strategy, personal life and character; some authors refer to "la misteriosa, ambigua y compleja personalidad del heredero carlista don Jaime", Andrés Martín 2000, p. 42, also Fernández Escudero 2012, p. 513

- some of his Carlist opponents noted that don Jaime was educated in "una Academia [the Austrian Military Academy] de ateos y escépticos y corrompidos" and somewhat light on his Catholic practices, Andrés Martín 2000

- Frans Coetzee, Marilyn Shevin Coetzee, Authority, Identity and the Social History of the Great War, New York 1995, ISBN 9781571810670, p. 277

- for overview of Polish stereotypes held about Russians, see Виктор Хорев (ed.), Россия – Польша. Образы и стереотипы в литературе и культуре, Москва 2002, ISBN 5857592143, Andrzej de Lazari (ed.), Katalog wzajemnych uprzedzeń Polaków i Rosjan, Warszawa 2006, ISBN 8389607654, pp. 303–327, Joanna Dzwończyk, Robert Jakimowicz, Stereotypy w stosunkach polsko-rosyjskich, [in:] Zeszyty Naukowe Akademii Ekonomicznej w Krakowie 611 (2002), pp. 103–116

- in 1890 Warsaw was rocked by a scandal ending in tragedy. Cornet of the Grodno Hussar Regiment, Александр Бартенев, shot a starlet of the Warsaw theatre, Maria Wisnowska. The culprit was allegedly intoxicated by opium. The incident was reported by the Polish press abroad, rather than in Warsaw, since Russian censorship imposed media blackout on the incident, compare the Lviv-based Gazeta Narodowa 27.07.90, available here. The same paper (issued in Austro-Hungary) agonized about allegedly lenient treatment of the culprit by Russian military and justice authorities

- see also comments about "life in Warsaw, known with some justification as little Paris", John Ernest Oliver Screen, Mannerheim: the Years of Preparation, London 1970, ISBN 9780900966224, p. 94. Gustaf Mannerheim served as a Russian cavalry officer in Poland since 1889, though in smaller garrison cities like Kalisz and Mińsk Mazowiecki. He was assigned to the Warsaw garrison (another life-guard regiment) few years after don Jaime had left it, in 1909, though the two might have met during the Russo-Japanese war. Unlike don Jaime, a foreigner unfamiliar with local political setting, Mannerheim was "acutely conscious of his position in the army that had been used to destroy the liberty of Poland" and went on with the locals very well

- Andrés Martín 2000, pp. 42–44 and onwards

- though it is difficult to imagine what other period he might have had in mind when noting in 1931 "many years I have spent in Russia", Clemente 1999, p. 161

- most detailed historiographical works on don Jaime do not mention Warsaw at all, referring only to service in the Russian army in general, see Andrés Martín 2000, Fernández Escudero 2012

- Bofarull 2006, p. 55

- Andrés Martín 2000, p. 94

- Jordi Canal, El carlismo, Madrid 2000, ISBN 8420639478, pp. 274–8, 282–8, 291–3

- Jan Kieniewicz, Hiszpania w polskim zwierciadle, Gdańsk 2001, ISBN 8385560742, Piotr Sawicki, Polska-Hiszpania, Hiszpania-Polska : poszerzanie horyzontów, Wrocław 2013, ISBN 9788360097212

- in Polish historiography the notable exception is Jacek Bartyzel, see his Umierać ale powoli, Kraków 2002, p. 286. More detailed comments in his Karlizm widziany z Polski, [in:] legitymizm.org service, available here

- "The Death of the Duke of Madrid", The Times (5 October 1931): 14.

- "Contradicts Reports of Zita's Poverty. The New York Times (15 June 1922): 6.

- "Legitimist Manifesto", The Times (24 April 1931), 14.

- "King Alfonso and the Duke of Madrid", The Times (25 September 1931): 12.

- "The Duke of Madrid at Fontainebleau", The Times (26 September 1931): 9.

External links

Bibliography

- Alcalá, César, Jaime de Borbón. El último rey romántico, Madrid 2011, ISBN 9788461475117

- "Don Jaime is Dead: Carlist Pretender". The New York Times (3 October 1931): 11.

- "The Duke of Madrid, Soldier and Traveller". The Times (5 October 1931): 19.

- Елец, Юлий Лукьянович, История Лейб-Гвардии Гродненского Гусарского полка, New York 2015, ISBN 9785519406048

- Andrés Martín, Juan Ramón de, El cisma mellista: historia de una ambición política. Madrid: Actas Editorial, 2000, ISBN 9788487863820

- Melgar del Rey, Francisco Melgar de, Don Jaime, el príncipe caballero. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1932.

- Melgar del Rey, Francisco Melgar de, El noble final de la escisión dinástica. Madrid: Consejo Privado de S.A.R. el Conde de Barcelona, 1964.

Jaime, Duke of Madrid Cadet branch of the House of Capetian Born: 27 June 1870 Died: 2 October 1931 | ||

| French nobility | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vacant Title last held by Louis Stanislas |

Duke of Anjou 1883 – 2 October 1931 |

Succeeded by Alfonso Carlos |

| Spanish nobility | ||

| Preceded by Carlos de Borbón |

Duke of Madrid 18 July 1909 – 2 October 1931 |

Vacant Title next held by Alfonso Carlosas Duke of San Jaime |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Preceded by Carlos VII (Charles XI) |

— TITULAR — King of Spain 18 July 1909 – 2 October 1931 |

Succeeded by Alfonso Carlos I (Charles XII) |

| — TITULAR — King of France and Navarre 18 July 1909 – 2 October 1931 | ||