Jáchymov

Jáchymov (Czech pronunciation: [ˈjaːxɪmof]), until 1945 known also by its German name of Sankt Joachimsthal or Joachimsthal (meaning "Saint Joachim's Valley"; German: Thal, or Tal in modern orthography) is a spa town in the Karlovy Vary Region of Bohemia, Czech Republic. It is situated at an altitude of 733 m (2,405 ft) above sea level in the eponymous St. Joachim's valley in the Ore Mountains, close to the Czech border with Germany.

Jáchymov Údolí Svatého Jáchyma | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Jáchymov in April 2016 | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

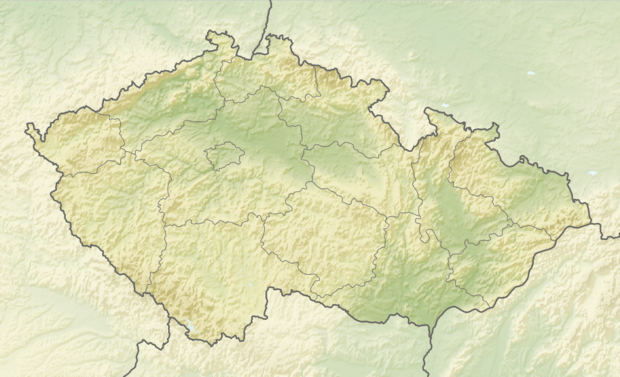

Jáchymov Location in the Czech Republic  Jáchymov Jáchymov (Europe) | |

| Coordinates: 50°21′58″N 12°55′24″E | |

| Country | Czech Republic |

| Region | Karlovy Vary |

| District | Karlovy Vary |

| First mentioned | 1510 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Bronislav Grulich |

| Area | |

| • Total | 51.11 km2 (19.73 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 672 m (2,205 ft) |

| Population (2006-07-03) | |

| • Total | 3,481 |

| • Density | 68/km2 (180/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 362 51 – 363 01 |

| Website | www |

The silver Joachimsthaler coins minted there since the 16th century became known in German as Thaler for short, which via the Dutch daalder or daler is the etymological origin of the currency name "dollar".[1][2][3]

History, mining and coinage

At the beginning of the 16th century, silver was found in the area of Joachimsthal. The village of Joachimsthal was founded in 1516 in place of the former abandoned village of Konradsgrun in order to facilitate the exploitation of this valuable resource. The silver caused the population to grow rapidly, and made the Counts von Schlick, whose possessions included the town, one of the richest noble families in Bohemia. The Schlicks had coins minted, which were called Joachimsthalers. They gave their name to the Thaler and the dollar. The fame of Joachimsthal for its ore mining and smelting works attracted the scientific attention of the doctor Georg Bauer (better known by the Latin form of his name, Georgius Agricola) in the late 1520s, who based his pioneering metallurgical studies on his observations made here.

In 1523, the Protestant Reformation began. In the Schmalkaldic War (1546–47) Joachimsthal was occupied for a time by Saxon troops. When in 1621 the Counter-reformation and re-Catholicisation took effect in the town, many Protestant citizens and people from the mountains migrated to nearby Saxony.[4]

Until 1918, the town (named Joachimsthal before 1898) was in the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, head of the district with the same name, one of the 94 Bezirkshauptmannschaften in Bohemia.[5]

In the 19th century the town was also the location of a Court, and of an administrative office responsible for mines and iron production. Mining was still significant in this period. It was run partly by state-owned and partly by privately owned firms. In addition to silver ore (of which in 1885 227 zentners (11.35 tonnes) were produced), nickel, bismuth and uranium ore were also extracted. There were also other industries: an enormous tobacco factory employed 1,000 women. In addition, there was the manufacture of gloves and corks and of bobbin lace.

On 31 March 1873 the town almost entirely burnt down.

At the end of the 19th century, Marie Curie discovered, in tons of pitchblende ore containing uraninite from Joachimsthal, the element radium, for which she won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Until the First World War this was the foremost source of radium in the world.[6]

The first radon spa in the world was founded in Joachimsthal in 1906, joining the famous spas of the region, including Karlsbad, Franzensbad, and Marienbad.

In 1929, Dr Löwy of Prague established that "mysterious emanations" in the mine led to a form of cancer. Ventilation and watering measures were introduced, miners were given higher pay and longer vacations, but death rates remained high.[7]

Following the Munich Agreement in 1938, it was annexed by Nazi Germany as part of the so-called Sudetenland. Most of the German-speaking population was expelled in 1945–1946 (see the Potsdam Agreement) and replaced by mostly non-German-speaking settlers from other parts of the country.

Modern town

After the Communist party took control of Czechoslovakia in 1948, large prison camps were established in the town and around it. Opponents of the new regime were forced to mine uranium ore under very harsh conditions: the average life expectancy in Jáchymov at this period was 42 years.

Uranium mining ceased in 1964. The radioactive thermal springs which arise in the former uranium mine are used under the supervision of doctors for the treatment of patients with nervous and rheumatic disorders. They make use of the constantly produced radioactive gas radon (222Rn) dissolved in the water, see Radon therapy.

Nearby attractions

Not far from here, at the foot of the Plešivec, there once stood the Capuchin monastery Mariasorg (Mariánská); it was razed to the ground in the 1950s.

From the valley of the Veseřice a chairlift goes to the highest peak in the Ore Mountains, the 1244-metre-high (4081′) Klínovec.

People

- Georgius Agricola (1494–1555), town doctor and chemist, the "Father of Mineralogy"

- Johannes Mathesius (1504–1565), from 1532 Rector of the Latin School and since 1542 "mine preacher" (Bergprediger)

- Samuel Fischer (1547–1600), professor, clergyman and Superintendent

See also

- Kutná Hora—another Bohemian silver mining town

References

- See also dollar at Wiktionary.

- Anderson, Hepzibah (May 28, 2019). "The Curious Origins of the Dollar". BBC. Retrieved May 28, 2019.

- Welcome to Jáchymov: the Czech town that invented the dollar BBC (www.bbc.com). January 8, 2020. Retrieved on 2020-01-09.

- More about history of the town in the 16th and 17th centuries for example in the article of Lukáš M. Vytlačil: Příběh renesančního Jáchymova [The Story of renaissance Jáchymov]. Evagelicus 2017, Praha 2016. pp. 42-45. (on-line here)

- Die postalischen Abstempelungen auf den österreichischen Postwertzeichen-Ausgaben 1867, 1883 und 1890, Wilhelm KLEIN, 1967

- Heinrich, E. Wm. (1958). Mineralogy and Geology of Radioactive Raw Materials. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. p. 283.

- Wiskemann, Elizabeth (1938). Czechs and Germans.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jáchymov. |

- Official website (in Czech)

- Historical photographs (in Czech)

- Historical photographs (portions of the above site in English)