Irene Papas

Irene Papas (or Pappas) (Greek: Ειρήνη Παππά, romanized: Eiríni Pappá [iˈrini paˈpa], born according to most sources on 3 September 1926)[1][2][3] is a Greek actress and singer who has starred in over 70 films in a career spanning more than 50 years. She became famous in Greece, and then internationally in feature films such as The Guns of Navarone and Zorba the Greek. She was a powerful protagonist in films including The Trojan Women and Iphigenia. She played the title roles in Antigone (1961) and Electra (1962).

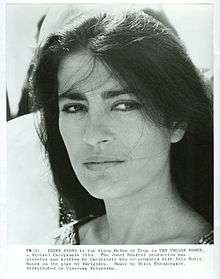

Irene Papas | |

|---|---|

Papas in 1956 | |

| Born | Irene Lelekou 3 September 1926 |

| Years active | 1948–2003 |

Papas won Best Actress awards in 1961 at the Berlin International Film Festival for Antigone and in 1971 from the National Board of Review for The Trojan Women. Her career awards include the Golden Arrow Award in 1993 at Hamptons International Film Festival, and the Golden Lion Award in 2009 at the Venice Biennale.

Personal life

Papas was born as Irini Lelekou (Ειρήνη Λελέκου) in the village of Chiliomodi, outside Corinth, Greece. Her mother, Eleni (née Prevedsanu), was a schoolteacher, and her father, Stavros, taught classical drama at the Sofikós school in Corinth. She was educated at the Royal School of Dramatic Art in Athens, taking classes in dance and singing.[4] In 1947 she married the film director Alkis Papas; they divorced in 1951.[5] In 1954 she met the actor Marlon Brando and they had a long and "secret love affair".[6] She married the film producer Jose Kohn in 1957; that marriage was later annulled.[5] She is the aunt of the film director Manousos Manousakis and the actor Aias Manthopoulos.[7]

In 2003 she served on the board of directors of the Anna-Marie Foundation, a fund which provided assistance to people in rural areas of Greece.[8] In 2018 it was announced that she had been suffering from Alzheimer's for five years.[9]

Film career

Papas debuted in American film with a bit part in the B-movie The Man from Cairo (1953); her next American film was a much larger role as Jocasta Constantine, alongside James Cagney, in the Western Tribute to a Bad Man (1956).[10] She was discovered by Elia Kazan in Greece, where she achieved widespread fame.[4][11] She then starred in films such as The Guns of Navarone (1961) and Zorba the Greek (1964), and critically acclaimed films such as Z (1969), where her political activist's widow has been called "indelible".[12] She was a leading figure in cinematic transcriptions of ancient tragedy, portraying Helen in The Trojan Women (1971) opposite Katharine Hepburn, Clytemnestra in Iphigenia (1977), and the title roles in Antigone (1961) and Electra (1962), where her portrayal of the "doomed heroine" is described as "outstanding".[11][13] She appeared as Catherine of Aragon in Anne of the Thousand Days, opposite Richard Burton and Geneviève Bujold in 1969. In 1976, she starred in Mohammad, Messenger of God about the origin of Islam. In 1982, she appeared in Lion of the Desert, together with Anthony Quinn, Oliver Reed, Rod Steiger, and John Gielgud. One of her last film appearances was in Captain Corelli's Mandolin in 2001.[4][14]

The Enciclopedia Italiana describes Papas as a typical Mediterranean beauty, with a lovely voice both in singing and acting, greatly talented and with an adventurous spirit.[4]

In the view of film critic Philip Kemp, Papas was an awe-inspiring presence, which paradoxically limited her career. He admired her roles in the films of Michael Cacoyannis, including the defiant Helen of Troy in The Trojan Women; the vengeful, grief-stricken Clytemnestra in Iphigenia; and "memorably"[11] as the cool but sensual widow in Zorba the Greek.[11] David Thomson, in his Biographical Dictionary of Film, called Papas's manner in Iphigenia "blatant declaiming".[15]

The film critic Roger Ebert observed that there were many "pretty girls" in cinema "but not many women", and called Papas a great actress. Ebert noted her uphill struggle, her height limiting the leading men she could play alongside, her accent limiting the roles she could take, and that "her unusual beauty is not the sort that superstar actresses like to compete with."[16] Ordinary actors, he suggested, had trouble sharing the screen with Papas. All the same, her presence in many well-known movies, wrote Ebert, inspired "something of a cult".[16]

The scholar of Greek Gerasimus Katsan calls her the most recognizable and best-known Greek film star, with "range, power, and subtlety", stating that her work made her a kind of national hero. She acted strong women with "beauty and sensuality, but also fierce independence and spirit".[17]

Theatre career

Papas began her acting career in variety and traditional theatre, in plays by Ibsen, Shakespeare, and classical Greek tragedy, before moving into film in 1951.[4] Later in her career, she took the title role in Medea in a 1973 production of Euripides's play. Reviewing the production in The New York Times, Clive Barnes described her as a "very fine, controlled Medea", smouldering with a "carefully dampened passion", constantly fierce.[18] Walter Kerr also praised Papas's Medea; both Barnes and Kerr saw in her portrayal what Barnes called "her unrelenting determination and unwavering desire for justice".[19] Albert Bermel considered Papas's rendering of Medea as a sympathetic woman a triumph of acting.[19]

Singing

In 1969, the RCA label released Papas' vinyl LP, Songs of Theodorakis (INTS 1033). This has 11 folk songs sung in Greek, conducted by Harry Lemonopoulos and produced by Andy Wiswell, with sleeve notes in English by Michael Cacoyannis. It was released on CD in 2005 (FM 1680).[20] Papas knew Mikis Theodorakis from working with him on Zorba the Greek[11] as early as 1964.

In 1972, she appeared on the album 666 by the Greek rock group Aphrodite's Child on the track "∞" (infinity). She chants "I was, I am, I am to come" repeatedly and wildly over a percussive backing, causing controversy with her "graphic orgasm".[21][22]

In 1979, Polydor released her solo album of eight Greek folk songs entitled Odes, with electronic music performed (and partly composed) by Vangelis Papathanassiou.[23] The lyrics were co-written by Arianna Stassinopoulos.[24] They collaborated again in 1986 for Rapsodies, an electronic rendition of seven Byzantine liturgy hymns, also on Polydor.[25]

Politics

Papas was a member of the Communist Party of Greece (KKE), and in 1967 called for a "cultural boycott" against the "Fourth Reich", meaning the military government of Greece at that time.[26] Her opposition to the regime sent her, and other artists such as Theodorakis whose songs she sang, into exile when the military junta came to power in Greece in 1967.[27][28]

Awards and honours

- 1961: 11th Berlin International Film Festival (Best Actress, for the film Antigone)[29][30]

- 1971: National Board of Review (Best Actress, for the film The Trojan Women)[31]

- 1973: Photo shoot with Magnum photographer Ferdinando Scianna[32]

- 1993: Golden Arrow Award for lifetime achievement, at Hamptons International Film Festival[33]

- 2009: Leone d'oro alla carriera (Golden Lion career award), Venice Biennale[34]

She has received the honours of Commander of the Order of the Phoenix in Greece, Commandeur des Arts et des Lettres in France, and Commander of the Civil Order of Alfonso X, the Wise in Spain.[35]

In 2017, it was announced that the National Theatre of Greece's drama school was to be relocated to a new "Irene Papas - Athens School" on Agiou Konstantinou Street in Athens from 2018.[36]

Discography

- Solo

- 1968 : Songs of Theodorakis

- 1990 : In Eleven Songs by Mikis Theodorakis

- With Vangelis

- Singles

- 1959 : Patience/Wick Walt Girls – With Trio Bel-Kanto and the Takis Morakis Orchestra

- 1969 : Per Te (Ta Afiso Ti Manula Mou)/Il Mio Aprile (Aprilis)

- 1970 : Requiem Per Chissa' Chi/La Soglia – Side A George Moustaki, Side B Irene Papas

- 1970 : La Soglia/So Cos'è.. – Taken from Irene Papas Canta Theodorakis

- 1979 : Les 40 Braves/Les Kolokotronei – Taken from the Odes album

- Collaborations

- 1972 : 666 from Aphrodite's Child - Chanting on ∞ (infinity)

- 2003 : (Άπονες Εξουσίες) – Heartless Authority from Mikis Theodorakis (2-CD compilation) – Papas sings backing vocals under the transliterated name "Irini Papa" on the whole of CD 1.

- 2005 : Mikis Theodorakis (5-CD Boxset compilation) – Papas sings on You were good and you were sweet under the name Er Pappa.

Filmography

- Fallen Angels (Greek, "Hamenoi angeloi", 1948) as Liana[37]

- Dead City (Greek, "Nekri Politeia", 1951) as Lena[11]

- The Unfaithfuls (Italian, "Le Infideli", 1953) as Luisa Azzali[11]

- Torna! (1953)

- The Man from Cairo (Italian, "Dramma del Casbah", 1953) as Yvonne Lebeau[11]

- One of Those (1953) as Monica (uncredited)

- Vortice (1953) as Clara[11]

- Theodora, Slave Empress (Italian, "Teodora, Imperatrice di Bisanzio", 1954) as Faidia[11]

- Attila (1954) as Grune[11]

- The Missing Scientists (1955) as Gina

- Tribute to a Bad Man (1956) as Jocasta Constantine[11]

- The Power and the Prize (1956)[11]

- Le avventure dei tre moschettieri (1957)

- La spada imbattibile (1957)

- Climax! (1958, TV Series) as Maxanne York

- Psit... koritsia! (1959) as Eleni

- I limni ton stenagmon (1959) as Frosyni

- Bouboulina (1959) as Laskarina Bouboulina

- The Guns of Navarone (1961) as Maria[11]

- Antigone (1961) as Antigone[11]

- Electra (1962) as Electra[11]

- The Moon-Spinners (1964) as Sophia[11]

- Zorba the Greek (1964) as the widow[11]

- Roger la Honte (1966) as Julia de Noirville[11]

- Zeugin aus der Hölle ("Witness out of Hell", 1966) as Lea Weiss[11]

- Ta skalopatia (1966)

- We Still Kill the Old Way (1967) as Luisa Roscio[11]

- The Desperate Ones (1967) as Ajmi[11]

- L'Odissea (1968, TV Mini-series) as Penelope[11]

- The Brotherhood (1968) as Ida Ginetta[11]

- Ecce Homo – I sopravvissuti (1968) as Anna[38]

- Z (1969) as Helene[11]

- A Dream of Kings (1969) as Caliope[11]

- Anne of the Thousand Days (1969) as Queen Katherine[11]

- The Trojan Women (1971) as Helen of Troy[11]

- Oasis of Fear (1971) as Barbara Slater

- Roma Bene (1971) as Elena Teopoulos[11]

- N.P. – Il segreto (1971) as the housewife[39]

- Don't Torture a Duckling (Italian, "Non si servizia un paperino", 1972) as Dona Aurelia Avallone[11]

- 1931: Once Upon a Time in New York (1972) as Donna Mimma[11]

- Battle of Sutjeska (1973)

- I'll Take Her Like a Father (1974)

- Moses the Lawgiver (Italian, "Mose", 1974) (TV miniseries) as Zipporah[11]

- Mohammad, Messenger of God (1976) as Hind[11]

- Blood Wedding (Spanish, "Bodas de Sangre", 1977)

- Iphigenia (1977) as Clytemnestra[11]

- Christ Stopped at Eboli (1979) as Giulia[11]

- Bloodline (1979) as Simonetta Palazza[11]

- Ring of Darkness (1979) as Raffaella[40]

- Lion of the Desert (1981) as Mabrouka[11]

- L'assistente sociale tutto pepe (1981)

- Eréndira (1983) as the grandmother[11]

- Il disertore (1983) as Mariangela[11]

- Melvin, Son of Alvin (1984)

- Into the Night (1985) as Shaheen Parvizi[11]

- The Assisi Underground (1985)

- Sweet Country (1987)

- Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1987)

- High Season (1987)

- A Child Called Jesus (1987) (TV film)

- Island (1989)

- Nirvana Street Murder (1990)

- Jacob (1994) (TV film)

- Party (1996) as Irene[11]

- The Odyssey (1997) (TV miniseries) as Anticlea[11]

- Anxiety ("Inquietude", 1998) as the mother[11]

- Yerma (1998)[11]

- Captain Corelli's Mandolin (2001) as Drosoula[14]

- A Talking Picture (2003) as Helena[41]

References

- Tsolka, Alexandra (15 February 2018). "Ειρήνη Παππά: Η γυναίκα – Ελλάδα (Irini Pappas: The woman - Greece)" (in Greek). Mononews.gr. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

Είναι 3 Σεπτεμβρίου 1926. (It is 3 September 1926)

|archive-url=is malformed: timestamp (help) - "Ειρήνη Παππά (Irene Pappas)". FinosFilm. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

Γεννήθηκε: 03 Σεπτεμβρίου 1926 ("Born: 3 September 1926")

- "Ειρήνη Παππά – Αυτή είναι η τελευταία Ελληνίδα θεά! (Irini Pappas - This is the last Greek goddess!)" (in Greek). Mikrofwno.gr. 3 September 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

"γεννήθηκε στο Χιλιομόδι Κορινθίας στις 3 Σεπτεμβρίου 1926" ("born at Chiliomodi, Corinth on 3 September 1926")

- "PAPAS, Irene, nata Lelekou". Enciclopedia Italiana - V Appendice (1994). Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Irene Papas Biography". Film Reference. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Williams, Steven (7 July 2004). "Irene Papas Comes Forward About A Love Affair With The Late Marlon Brando". Contact Music. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Cloudy Sunday". NY Sephardic Film Festival. 2016. Archived from the original on 9 March 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Press Conference on the developments regarding the 'Anna-Maria' Foundation", greekroyalfamily.org, 28 August 2003.

- "Irene Pappa: Her niece reveals all the truth about her state of health". Altsantiri. 9 July 2018. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- Katsan, Gerasimus (2016). "The Hollywood Films of Irene Papas". The Journal of Modern Hellenism. 32: 31–43.

- "Papas, Irene". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 27 February 2017.; Kemp, Philip (2001). "Irene Papas". International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers. Gale Group.

- Monaco, James (1991). The Encyclopedia of Film. Perigee Books. p. 414. ISBN 978-0-399-51604-7.

- "Electra / Elektra". The Sydney Greek Film Festival 2006. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Elley, Derek (24 April 2001). "Review: 'Captain Corelli's Mandolin'". Variety. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Thomson, David (2010). The New Biographical Dictionary Of Film (5th ed.). Little, Brown. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-7481-0850-3.

- Ebert, Roger (13 July 1969). "Interview with Irene Papas". Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Katsan, Gerasimus (2016). "The Hollywood Films of Irene Papas". Journal of Modern History. 32: 31–43.

- Barnes, Clive (18 January 1973). "Stage: Circle Presents New 'Medea'". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Hartigan, Karelisa (1995). Greek Tragedy on the American Stage: Ancient Drama in the Commercial Theater, 1882-1994. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 53–55. ISBN 978-0-313-29283-5.

- "Irene Pappas Sings Mikis Theodorakis". FM Records. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Dome, Malcolm (27 January 2015). "Malcolm Dome looks back on the impact of Aphrodite's Child's mythic prog masterpiece". Retrieved 27 February 2017.

The band's label, Mercury, were certainly left bemused. In fact, they were so horrified by the scope and challenge of the double album that they initially refused to release it. In particular, Papas' graphic orgasm during Infinity struck the wrong chord with them. Eventually, the company relented and agreed to put it out on their Vertigo imprint.

- Henshaw, Laurie (19 August 1972). "The Greeks have a word for it". Melody Maker. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- Trunk, Jonny. "Vangelis & Irene Papas - Odoes [sic]". Record Collector magazine. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Vangelis and Irene Papas lyrics - Odes lyrics (English translation)". Lyrics of Music by Vangelis. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

(Greek) Lyrics: Irene papas and Arianna Stassinopoulos.

- Trunk, Jonny (November 2007). "Vangelis & Irene Papas - Rapsodies". Record Collector magazine. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Irene Pappas Asks Boycott Of Greece's 'Fourth Reich'". The New York Times. 20 July 1967. Retrieved 27 February 2017.

- "Irene Papas | Das Porträt" (in German). Neues Deutschland | Sozialistische Tageszeitung. 1 November 2001. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- Loutzaki, Irene (2001). "Folk Dance in Political Rhythms". Yearbook for Traditional Music. 33: 127–137. JSTOR 1519637.

- Sloan, Jane (2007). Reel Women: An International Directory of Contemporary Feature Films about Women. Scarecrow Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-1-4616-7082-7.

- Tzavalas, Trifon (2012). Greek Cinema Volume 1 100 Years of Film History 1900-2000 (PDF). Hellenic University Club of Southern California. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-938385-11-7.

Irene Pappas received the Best Performance Award.

- "Awards for 1971". National Board of Review. Archived from the original on 16 March 2004. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- "Ferdinando Scianna - IRENE PAPAS". Magnum Photos. 1973. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Awards at Hamptons Film Festival". The New York Times. 25 October 1993. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- "Irene Papas Leone d' oro alla carriera". La Repubblica (in Italian). 20 February 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

Noi italiani la ricordiamo ancora come la bella Penelope dell' Odissea tv (anno 1969): Irene Papas la grande attrice greca, riceve alle 18 il Leone d' oro alla carriera del Festival Internazionale del Teatro della Biennale di Venezia diretto da Maurizio Scaparro dedicato al Mediterraneo che si apre oggi. L' attrice interpreterà "Medea", nell' originale di Euripide e nella riscrittura di Corrado Alvaro.

- "Irene Papas" (in German). Who's Who. 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "Relocation of the Drama School to the "Irene Papas - Athens School" | National Theatre of Greece". Latsis Foundation. 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2018.

- "Irene Papas". Cinemagraphe. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

- "Ecce Homo – I sopravvissuti". FilmTV.it. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "N.P. Il Segreto (1970)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "Un' Ombra Nell'Ombra (1979)". British Film Institute. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

- "A Talking Picture". Variety. Retrieved 30 August 2018.

External links

- Irene Papas on IMDb

- Irene Papas at the Internet Broadway Database

- Irene Papas Discography

- Irène Papas regarding her work as an actress (video interview with context and transcript) from Europe of Cultures, 1 June 1980