Gloria Swanson

Gloria May Josephine Swanson (March 27, 1899 – April 4, 1983) was an American actress and producer. She starred in dozens of silent films, and was nominated three times for an Academy Award as Best Actress. She was born in Chicago, and raised in a military family that moved from base to base. Her school girl crush on Essanay Studios actor Francis X. Bushman led to her aunt taking her to tour the actor's studio when they were living in Chicago. The then 15-year-old Swanson was offered a brief walk-on for one film, as an extra. As a result of the walk-on, she was offered $13.25 a week as a recurring film extra, so she quit school to begin what would become her life's career in front of the cameras. Swanson was soon hired to work in California for Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios comedy shorts opposite Bobby Vernon. She was eventually recruited by Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount Pictures, where she was put under contract for seven years.

Gloria Swanson | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Swanson in 1922 | |

| Born | Glory May Josephine Swanson March 27, 1899 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | April 4, 1983 (aged 84) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Church of the Heavenly Rest, New York City |

| Other names | Gloria Mae |

| Education | Hawthorne Scholastic Academy |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1914–1983 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 3 |

| Signature | |

In 1925, Swanson joined United Artists, as one of the film industry's pioneering women producers. She hired Raoul Walsh in 1927 to direct Sadie Thompson about the travails of a prostitute living in American Samoa. Her performance in the lead role earned Swanson a nomination for Best Actress at the first annual Academy Awards. George Barnes was nominated for his cinematography of the film. In 1929, Swanson made her debut sound film with her performance in The Trespasser, which earned her a second Academy Award nomination. Personal problems and changing tastes saw her popularity wane during the 1930s and she ventured into theatre and television. After not having acted in a film for nine years, she was hailed for her comeback role in the 1950 film Sunset Boulevard. Her performance earned her a Golden Globe Award and a nomination for an Academy Award. In 1995, the film was chosen by the Library of Congress for preservation as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant." She only made 3 more films after Sunset Boulevard, but guest starred on several television shows, and acted in road productions of stage plays.

She was married six times, and was the mother of three children. Among the men she had extra-marital affairs with were businessman (and later U. S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom) Joseph P. Kennedy Sr., and actor Herbert Marshall. In his divorce filing, her second husband Herbert K. Somborn accused her of having affairs with 13 men. Swanson was a vegetarian and health food advocate, whose sixth husband William Dufty was also a health advocate, as well as being the ghost writer of her autobiography Swanson on Swanson. In 1980, Swanson sold the bulk of her archives to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

Early life

She was born Gloria May Josephine Swanson in a small house in Chicago in 1899, the only child of Adelaide (née Klanowski) and Joseph Theodore Swanson, a soldier. She attended Hawthorne Scholastic Academy. She was raised in the Lutheran faith. Her father was a Swedish American, and her mother was of German, French, and Polish ancestry.[1][2] Because of her father's attachment to the U.S. Army, the family moved frequently. She spent some of her childhood in Key West, Florida, where she was enrolled in a Catholic convent school,[3] and in Puerto Rico and where she saw her first motion pictures.[4]

Career

1914–1918: Essanay/Keystone/Triangle

Her family once again residing in Chicago, the adolescent Gloria developed a crush on actor Francis X. Bushman, and knew he was employed by Essanay Studios in the city. Swanson would later recall that her Aunt Inga brought her at age 15 to visit Bushman's studio, where she was discovered by a tour guide. Other accounts have the star-struck Swanson herself talking her way into the business. In either version, she was soon hired as an extra.[5]

The movie industry was still in its infancy, churning out short subjects, without the advantage of today's casting agencies and talent agents promoting their latest find. A willing extra was often a valuable asset. Her first role was a brief walk-on with actress Gerda Holmes, that paid an enormous (in those days) $3.25. That first non-credited film is believed to have been in the 1914 The Song of Soul.[6] The studio soon offered her steady work at $13.25 (equivalent to $338 in 2019) per week. Swanson left school to work full-time at the studio.[7] In 1915, she co-starred in Sweedie Goes to College with her future first husband Wallace Beery.[8]

Swanson's mother accompanied her to California in 1916 for her roles in Mack Sennett's Keystone Studios comedy shorts opposite Bobby Vernon, and directed by Clarence G. Badger. They were met at the train station by Beery, who was pursuing his own career ambitions at Keystone.[9] Vernon and Swanson projected a great screen chemistry that proved popular with audiences. Director Charley Chase recalled that Swanson was "frightened to death" of Vernon's dangerous stunts.[10] Surviving movies in which they appear together include The Danger Girl (1916), The Sultan's Wife (1917), and Teddy at the Throttle (1917). Badger was sufficiently impressed by Swanson to recommend her to director Jack Conway for Her Decision and You Can't Believe Everything in 1918. Triangle had never put Swanson under contract, but did increase her pay to $15 a week. When she was approached by Famous Players-Lasky to work for Cecil B. DeMille, the resulting legal dispute obligated her to Triangle for several more months. Soon afterwards, Triangle was in a financial bind and loaned Swanson to DeMille for the comedy Don't Change Your Husband.[11]

1919–1926: Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount Pictures

At the behest of DeMille, Swanson signed a contract with Famous Players-Lasky on December 30, 1918, for $150 a week, to be raised to $200 a week, and eventually $350 a week.[12] Her first picture under her new contract was DeMille's World War I romantic drama For Better, for Worse.[13] She made six pictures under the direction of DeMille, including Male and Female (1919) in which she posed with a lion as "the Lion's Bride". While she and her father were dining out one evening, the man who would become her second husband, Equity Pictures president Herbert K. Somborn, introduced himself, by inviting her to meet one of her personal idols, actress Clara Kimball Young.[14]

Why Change Your Wife? (1920), Something to Think About (1920), and The Affairs of Anatol (1921)[15] soon followed. During her time at Famous Players-Lasky, eight of her films were directed by Allan Dwan. She appeared in 10 films directed by Sam Wood, including Beyond the Rocks in 1922 with her longtime friend Rudolph Valentino.[16] He had become a star in 1921 for his appearance in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, but Swanson had known him since his days as an aspiring actor getting small parts, with no seeming hope for his professional future. She was impressed by his shy, well-mannered personality, the complete opposite of what his public image would become.[17]

In 1925, Swanson starred in the French-American comedy Madame Sans-Gêne, directed by Léonce Perret. Filming was allowed for the first time at many of the historic sites relating to Napoleon. While it was well received at the time, no prints are known to exist, and it is considered to be a lost film. During the production of Madame Sans-Gêne, Swanson met her third husband Henri, Marquis de la Falaise,[18] who had been hired to be her translator during the film's production. After a four-month residency in France she returned to the United States as European nobility, now known as the Marquise. She got a huge welcome home with parades in both New York and Los Angeles. Swanson appeared in a 1925 short produced by Lee DeForest in his Phonofilm sound-on-film process. She made a number of films for Paramount, including The Coast of Folly, Stage Struck and Fine Manners.[19]

1925–1933: United Artists

She turned down a one-million-dollar-a-year (equivalent to $14,700,000 in 2019) contract with Paramount to join the newly created United Artists partnership on June 25, 1925, accepting a 6-picture distribution offer from president Joseph Schenck. At the time, Swanson was considered the most bankable star of her era.[20] United Artists had its own Art Cinema Corporation subsidiary to advance financial loans for the productions of individual partners.[21] The partnership agreement included her commitment to a buy-in of $100,000 of preferred stock subscription.[22] Before she could produce films with United Artists, she fulfilled her existing agreement with Paramount for two more films.

Swanson Producing Corporation

The Swanson Producing Corporation was set up as the umbrella organization for her agreement with United Artists. Under that name, she produced The Love of Sunya with herself in the title role. The film was directed by Albert Parker, based on the play The Eyes of Youth, by Max Marcin and Charles Guernon. It co-starred John Boles and Pauline Garon. The production had been a disaster, with Parker being indecisive, and the actors not experienced enough to deliver the performances she wanted. The film fell behind in its schedule, and by the time of its release, the end product had not lived up to Swanson's expectations. While it did not lose money, it was a financial wash, breaking even on the production costs.[23][24]

Gloria Swanson Productions

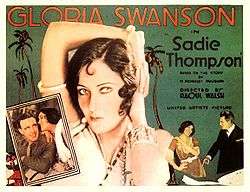

She engaged the services of director Raoul Walsh in 1927, and together they conceived of making a film based on W. Somerset Maugham's short story "Miss Thompson".[25] Gloria Swanson Productions proposed to film the controversial Sadie Thompson about the travails of a prostitute living in American Samoa, a project that initially pleased United Artists president Joseph Schenck.[26] As she moved forward with the project, association members urged Schenck to halt the production due to its subject matter. The members took further steps by registering their discontent with Will H. Hays, Chairman of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America.[27] Walsh previously had his own battles with the Hays office, having managed to skirt around censorship issues with What Price Glory?. [28] By bringing him to the table, literally over breakfast in her home, Hays and Swanson developed a working relationship for the film.[29] Hays was enthusiastic about the basic story, but did have specific issues that were dealt with before the film's release. The project was filmed on Santa Catalina Island, just off the coast of Long Beach, California. Gross receipts slightly exceeded $850,000 (equivalent to $12,500,000 in 2019) At the first annual Academy Awards, Swanson received a nomination for Best Actress for her performance, and the film's cinematographer George Barnes was also nominated.[30]

Gloria Productions

By the end of 1927, Swanson was in dire financial straits, with only $65 in the bank.[31] Her two productions had generated income, but too slowly to offset her production loan debts to Art Cinema Corporation. Swanson had also not made good on her $100,000 subscription for preferred United Artists shared stock. She had received financial proposals from United Artists studio head Joseph Schenck, as well as from Bank of America, prior to engaging the services of Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. as her financial advisor. He proposed to personally bankroll her next picture, and conducted a thorough examination of her financial records.[32] Kennedy advised her to shut down Swanson Producing Corporation. She agreed to his plan for a fresh start under the dummy corporate name of Gloria Productions, headquartered in Delaware. Upon his advice, she fired most of her staff, and sold her rights for The Love of Sunya and Sadie Thompson to Art Cinema Corporation.[33] Kennedy then created the position of "European director of Pathé" to put her third husband Henry de La Falaise on the payroll.[34]

Sound films were already becoming popular with audiences, most notably the films of singer Al Jolson, who had success with The Jazz Singer released in 1927 and The Singing Fool in 1928. Kennedy, however, advised her to hire Erich von Stroheim to direct another silent film, The Swamp, subsequently retitled Queen Kelly. She was hesitant to hire Stroheim, who was known for being difficult to deal with, and who was unwilling to work within any budget. Kennedy, nevertheless, was insistent, and was able to get Stroheim released from contractual obligations to producer Pat Powers.[35] Stroheim worked for several months on writing the basic script, and filming of Queen Kelly began in November.[36] His filming was slow, albeit meticulous, and the cast and crew suffered from long hours. Shooting was shut down in January, and Stroheim fired, after complaints by Swanson about him and about the general direction the film was taking. Swanson and Kennedy tried to salvage it with an alternative ending shot on November 24, 1931, directed by Swanson and photographed by Gregg Toland. The film was not released theatrically in the United States, but was shown in Europe and South America.[37]

Only two other films were made under Gloria Productions. The Trespasser in 1929 was filmed as a silent and later re-dubbed as a sound production. It earned Swanson her second Oscar nomination.[38] What a Widow! in 1930 was the final film for Gloria Productions, but was her first production originally filmed with sound.[39][40]

United Artists stars on the radio

Mary Pickford and her husband Douglas Fairbanks hosted the March 29, 1928 episode of the Dodge Hour radio program, originating from Pickford's private bungalow at United Artists, and broadcast to audiences in American movie theaters.[41] The brainchild of Joseph Schenck, it was a promotional come-on to attract audiences into movie theaters to hear the voices of their favorite actors, as sound productions became the future of commercial films. On hand were Swanson, Charlie Chaplin, Norma Talmadge, John Barrymore, Dolores del Río and D. W. Griffith.[42]

Gloria Swanson British Productions Ltd.

Perfect Understanding was a 1933 sound production comedy filmed by Gloria Swanson British Productions Ltd, and the only film produced by this company. Made entirely at Ealing Studios, it co-starred Laurence Olivier as Swanson's on-screen husband. United Artists bought back all of her stock with them, in order to provide her financing to make this film, and thereby ending her relationship with the partnership. [43] The film was panned by the critics upon its release, and failed at the box office.[44]

1938–1950: Creating new paths

When she made the transition to sound films as her career simultaneously began to decline, Swanson moved permanently to New York City in 1938. Swanson starred in Father Takes a Wife for RKO in 1941.[45] She began appearing in the stage productions, and starred in The Gloria Swanson Hour on WPIX-TV in 1948.[46] Swanson threw herself into painting and sculpting, and in 1954, published Gloria Swanson’s Diary, a general newsletter.[47] She toured in summer stock, engaged in political activism, designed and marketed clothing and accessories, and made personal appearances on radio and in movie theaters.[45]

1950 – 1977: Later career

Sunset Boulevard

The film Sunset Boulevard was conceived by director Billy Wilder and screenwriter Charles Brackett, and came to include writer D. M. Marshman Jr. They bandied about the names of Mae West and Mary Pickford for the lead role of Norma Desmond. It was director George Cukor who suggested Swanson, once such a valuable asset to her studio that she was, "...carried in a sedan chair from her dressing room to the set.”[48] The storyline has faded silent movie star Desmond falling in love with the younger screenwriter Joe Gillis, played by William Holden. Desmond lives in the past, assisted by her former-director-turned-butler Max, played by Erich von Stroheim, who personally disliked the role and only agreed to it out of financial need.[49] A clip from Stroheim's Queen Kelly was used for the scene where Desmond and Gillis are watching one of her old silent movies, and she declares, "... we didn't need dialogue, we had faces".[50]

As Gillis sits on the side next to Desmond, she plays poker with a group he refers to as "the Waxworks": actors Buster Keaton, H.B. Warner and Anna Q. Nilsson. During the scene leading up to Cecil B. DeMille's cameo, where Max chauffeurs Desmond to the studio, her Isotta-Fraschini luxury automobile was towed from behind the camera, because Stroheim had never learned to drive.[51] At the studio, Desmond's dreams of a comeback are subverted, and she threatens to kill herself, but instead fatally shoots Gillis. She becomes totally delusional by the time the police and news media arrive. Max sets up studio lighting towards her on the staircase, and directs her down towards the waiting police and news cameras, where she looks directly into the camera and says, "All right, Mr. DeMille, I'm ready for my close-up."[52]

Swanson so enjoyed making the movie that she later stated, "I hated to have the picture end ... When Mr. Wilder called ‘Print it!’ I burst into tears...”[53] She was nominated for a Best Actress Academy Award, but lost out to Judy Holliday.[54]

In 1995, the Library of Congress chose Sunset Boulevard as one of four Wilder films, "to be preserved in the permanent collection of the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress as culturally, historically, and aesthetically important". The other three films were Some Like It Hot, The Apartment and Double Indemnity.[55]

Final films

Swanson received several acting offers following the release of Sunset Boulevard, but turned most of them down, saying they tended to be pale imitations of Norma Desmond. Her last major Hollywood motion picture role was the poorly received Three for Bedroom "C" in 1952. Nationally syndicated columnist Suzy called it "one of the worst movies ever made."[56] In 1956, Swanson made Nero's Mistress, which starred Alberto Sordi, Vittorio de Sica and Brigitte Bardot.[57] Her final screen appearance was as herself in Airport 1975.[57]

Television and theatre

Swanson hosted The Gloria Swanson Hour, one of the first live television series in 1948, in which she invited friends and others to be guests. Swanson later hosted Crown Theatre with Gloria Swanson, a television anthology series, in which she occasionally acted.[58]

Through the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, Swanson appeared on many different talk and variety shows such as The Carol Burnett Show in 1973 and The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, to recollect her movies and to lampoon them as well. She was twice the "mystery guest" on What's My Line. She acted in "Behind the Locked Door" on The Alfred Hitchcock Hour in 1964, and in the same year, she was nominated for a Golden Globe award for her performance in Burke's Law.[59] She made a guest appearance on The Dick Cavett Show in the summer of 1970; a guest on the same show as Janis Joplin, who died later that year.[60] She made a notable appearance in a 1966 episode of The Beverly Hillbillies, titled "The Gloria Swanson Story", in which she plays herself. In the episode, the Clampetts mistakenly believe Swanson is destitute, and decide to finance a comeback movie for her – in a silent film.[61]

After near-retirement from movies, Swanson appeared in many plays throughout her later life, beginning in the 1940s. Actor and playwright Harold J. Kennedy, who had learned the ropes at Yale and with Orson Wells' Mercury Theatre, suggested Swanson do a road tour of "Reflected Glory", a comedy that had run on the Broadway stage with Tallulah Bankhead as its star.[62] Kennedy wrote the script for the play A Goose for the Gander, which began its road tour in Chicago in August 1944.[63][64][65]

Swanson also toured with Let Us Be Gay. After her success with Sunset Boulevard, she starred on Broadway in a revival of Twentieth Century with José Ferrer, and in Nina with David Niven. Her last major stage role was in the 1971 Broadway production of Butterflies Are Free at the Booth Theatre. Swanson appeared on The Carol Burnett Show in 1973, doing a sketch wherein she flirted with Lyle Waggoner. The episode was titled "Carol and Sis/The Guilty Man."[66]

In 1980, Swanson's autobiography Swanson on Swanson, ghost written by her husband William F. Dufty,[67] was published and became a commercial success. Kevin Brownlow and David Gill interviewed her for Hollywood, a television history of the silent era.[68]

Personal life

Swanson was a vegetarian and an early health food advocate[69] who was known for bringing her own meals to public functions in a paper bag. In 1975, Swanson traveled the United States and helped to promote the book Sugar Blues written by her husband, William Dufty.[70]

Swanson's autobiography Swanson on Swanson was ghost written by her husband William Dufty in 1980, and published by Random House.[71] The same year, she designed a stamp cachet for the United Nations Postal Administration.[72]

She was a pupil of the yoga guru Indra Devi, and was photographed performing a series of yoga poses, reportedly looking much younger than her age, for Devi to use in her book Forever Young, Forever Healthy; but the publisher Prentice-Hall decided to use the photographs for Swanson's book, not Devi's. In return, Swanson, who normally never did publicity events, helped to launch Devi's book at the Waldorf-Astoria in 1953.[73]

In 1964, Swanson spoke at a "Project Prayer" rally attended by 2,500 at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. The gathering, which was hosted by Anthony Eisley, a star of ABC's Hawaiian Eye series, sought to flood the United States Congress with letters in support of mandatory school prayer, following two decisions in 1962 and 1963 of the United States Supreme Court, which struck down mandatory prayer as conflicting with the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution.[74] Joining Swanson and Eisley at the Project Prayer rally were Walter Brennan, Lloyd Nolan, Rhonda Fleming, Pat Boone, and Dale Evans. Swanson declared "Under God we became the freest, strongest, wealthiest nation on earth, should we change that?"[74]

Marriages and relationships

Wallace Beery

Wallace Beery and Swanson married on her 17th birthday on March 27, 1916, but by her wedding night she felt she had made a mistake, and saw no way out of it. She didn't like his home or his family, and was repulsed by him as lover. After becoming pregnant, she saw her husband with other women and learned he had been fired from Keystone. Taking medication given to her by Beery, purported to be for morning sickness, when she aborted the fetus, she was taken unconscious to hospital. Soon afterwards, she filed for divorce, which was not finalized until December 13, 1918.[75][76] Under California law in that era, there was a one-year waiting period after a divorce was granted, before it became finalized, and either of the parties could remarry.[77]

Herbert K. Somborn

She married Herbert K. Somborn on December 20, 1919.[78] He was at that time president of Equity Pictures Corporation and later the owner of the Brown Derby restaurant. Their daughter, Gloria Swanson Somborn was born October 7, 1920.[79] In 1923, she adopted 1-year-old Sonny Smith, whom she renamed Joseph Patrick Swanson after her father.[80] During their divorce proceedings, Somborn accused her of adultery with 13 men, including Cecil B. DeMille, Rudolph Valentino and Marshall Neilan.[81] The public sensationalism led to Swanson having a "morals clause" added to her studio contract.[82] Somborn was granted a divorce in Los Angeles, on September 20, 1923.[83]

Henri de la Falaise

Gloria Swanson, 1950

Swanson's third husband was French aristocrat Henri, Marquis de la Falaise de la Coudraye, whom she married on January 28, 1925, after the Somborn divorce was finalized. Though Henri was a Marquis and the grandson of Richard and Martha Lucy Hennessy from the famous Hennessy Cognac family, he had no personal wealth.[85] They met in 1925 when he was hired to be her assistant and interpreter in France during her filming of Madame Sans-Gêne.

She conceived a child with him before her divorce from Somborn was final, a situation that would have led to a public scandal, and possible end of her film career. She subsequently had an abortion, which she later regretted.[86] He became a film executive representing Pathé (USA) in France.[33] This marriage ended in divorce in 1930.

In spite of the divorce, they remained close, and he became a partner in her World War II efforts to aid potential scientist refugees fleeing from behind Nazi lines. In 1939, Swanson created Multiprises, an inventions and patents company. Henri de la Falaise, provided a transitional Paris office for the scientists and gave written documentation to authorities guaranteeing jobs for them.[87] Scientist Richard Kobler, chemist Leopold Karniol, metallurgist Anton Kratky, and scientist Leopold Neumann, were brought to New York and headquartered in Swanson's apartment. The group nicknamed her "Big Chief".[88]

Joseph P. Kennedy

While still married to Henri, Swanson had a lengthy affair with the married Joseph P. Kennedy, father of future President John F. Kennedy. He became her business partner and their relationship was an open secret in Hollywood. He took over all of her personal and business affairs and was supposed to make her millions.[32] Kennedy left her after the disastrous Queen Kelly.[89]

Michael Farmer

After the marriage to Henri and her affair with Kennedy were over, Swanson became acquainted with Michael Farmer, the man who would become her fourth husband. They met by chance in Paris when Swanson was being fitted by Coco Chanel for her 1931 film Tonight or Never. Farmer was a man of independent financial means, who seemed to not have been employed. Rumors were that he was a kept man. Swanson began spending time with him.[90] Swanson had a breast lump, she became pregnant, but was not yet divorced from Henry (or Henri). She wasn't interested in marrying Farmer, but he didn't want to break off the relationship.. When Farmer found out she was pregnant, he threatened to go public with the news unless she agreed to marry him, something she did not want to do. Her friends, some of whom openly disliked him, thought she was making a mistake. They married on August 16, 1931, and divorced 2 years later.[91]

Because of the possibility that Swanson's divorce from La Falaise had not been final at the time of the wedding, she was forced to remarry Farmer the following November, by which time she was four months pregnant with Michelle Bridget Farmer, who was born on April 5, 1932.[92]

Herbert Marshall

Swanson and Farmer divorced in 1934 after she became involved with married British actor Herbert Marshall. The media reported widely on her affair with Marshall.[93][94][95] After almost three years with the actor, Swanson left him once she became convinced he would never divorce his wife, Edna Best, for her. In an early manuscript of her autobiography written in her own hand decades later, Swanson recalled "I was never so convincingly and thoroughly loved as I was by Herbert Marshall."[96]

William M. Davey

Davey was a wealthy investment broker whom Swanson met in October 1944 while she was appearing in A Goose for the Gander. They married four months later. Swanson had initially thought she was going to be able to retire from acting, but the marriage was troubled by Davey's alcoholism from the start. Erratic behavior and acrimonious recriminations followed. Swanson and her daughter Michelle Farmer began attending Alcoholics Anonymous meetings to cope, and left AA pamphlets around the apartment.[97] Davey moved out. In the subsequent legal separation proceedings, the judge ordered him to pay Swanson alimony. In an effort to avoid the payments, Davey unsuccessfully filed for divorce on the grounds of mental cruelty. He died within a year, not having paid anything to Swanson, and left the bulk of his estate to the Damon Runyon Memorial Fund.[98] [99]

William Dufty

Swanson's final marriage occurred in 1976 and lasted until her death. Her sixth husband William Dufty, a book ghost-writer and newspaperman who worked for many years at the New York Post, where he was assistant to the editor from 1951 to 1960. He was the co-author (ghost writer) of Billie Holiday's autobiography Lady Sings the Blues, the author of Sugar Blues, a 1975 best-selling health book still in print, and the author of the English version of Georges Ohsawa's You Are All Sanpaku. He first met Swanson in 1965 and by 1967 the two were living together as a couple. Swanson shared her husband's enthusiasm for macrobiotic diets, and they traveled widely together to speak about nutrition. They promoted his book Sugar Blues together in 1975, and co-authored a syndicated column.[100] It was through Sugar Blues that Dufty and Swanson first got to know John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Swanson testified on Lennon's behalf at his immigration hearing in New York, which led to him becoming a permanent resident.[101] Dufty ghost-wrote Swanson's best-selling 1980 autobiography, Swanson on Swanson[102] based on her drafts and notes, while she revised it several times.[103] They were prominent socialites, having many homes and living in many places, including New York City, Rome, Portugal, and Palm Springs, California. After Swanson's death, Dufty returned to his former home in Birmingham, Michigan. He died of cancer in 2002.[102]

Political views

Swanson was a Republican and supported the 1940 and 1944 campaigns for president of Wendell Willkie, and the 1964 presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater.[104] In 1980, she chaired the New York chapter of Seniors for Reagan-Bush.[105]

Death

Shortly after returning to New York from her home in the Portuguese Riviera, Swanson died in New York City in New York Hospital in April 1983 from a heart ailment, aged 84.[106][107] She was cremated and her ashes interred at the Episcopal Church of the Heavenly Rest on Fifth Avenue in New York City, attended by only a small circle of family. The church was the same one where the funeral of Chester A. Arthur took place.[108]

After Swanson's death, there was a series of auctions from August to September 1983 at William Doyle Galleries in New York of the star's furniture and decorations, jewelry, clothing, and memorabilia from her personal life and career.

Honors and legacy

In 1960, Gloria Swanson was honored with two stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame: one for motion pictures at 6750 Hollywood Boulevard, and another for television at 6301 Hollywood Boulevard.[109] In 1955 and 1957, Swanson was awarded The George Eastman Award, given by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film, and in 1966, the museum honored her with a career film retrospective, titled A Tribute to Gloria Swanson, which screened several of her movies.[110] In 1974, Swanson was one of the honorees of the first Telluride Film Festival.[111] A parking lot by Sims Park in downtown New Port Richey, Florida is named after the star, who is said to have owned property along the Cotee River.

In 1982, a year before her death, Swanson sold her archives of over 600 boxes for an undisclosed sum, including photographs, artwork, copies of films and private papers, including correspondence, contracts and financial dealings to the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin. Upon her 1983 death, much of the remainder of her holdings were purchased by UT-Austin at an auction held at the Doyle New York gallery. An undisclosed amount on memorabilia was also gifted to the HRC Center between 1983–88.[112]

Portrayals

Swanson has been played both on television and in film by the following actresses:

- 1984: Diane Venora in The Cotton Club[113]

- 1990: Madolyn Smith in The Kennedys of Massachusetts[114]

- 1991: Ann Turkel in White Hot: The Mysterious Murder of Thelma Todd[115]

- 2008: Kristen Wiig in Saturday Night Live[116]

- 2013: Debi Mazar in Return to Babylon[117]

Gallery

Stage

Note: The list below is limited to New York/Broadway theatrical productions

| Date | Title | Role | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 23, 1945 – Feb 03, 1945 | A Goose for the Gander | Katherine | [118] |

| Mar 26, 1947 – Apr 19, 1947 | Bathsheba | [119] | |

| Dec 24, 1950 – Jun 02, 1951 | Twentieth Century | Lily Garland | [120] |

| Dec 05, 1951 – Jan 12, 1952 | Nina | Nina | [121] |

| Sep 07, 1971 – Jul 02, 1972 | Butterflies Are Free | Mrs. Baker | [122] |

Filmography

Shorts

| Year | Title | Role | Notes Studio/Distributor |

Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1914 | The Song of the Soul | Unconfirmed | [6] | |

| 1915 | The Misjudged Mr. Hartley | Maid | [6] | |

| 1915 | At the End of a Perfect Day | Hands Bouquet to Holmes | Uncredited | [6] |

| 1915 | The Ambition of the Baron | Bit part | Essanay Film starring Francis X. Bushman |

[123] |

| 1915 | His New Job | Stenographer | Essanay Film Written and directed by Charlie Chaplin |

[6] |

| 1915 | The Fable of Elvira and Farina and the Meal Ticket | Farina, Elvira's Daughter | Credited as Gloria Mae Essanay Film |

[6] |

| 1915 | Sweedie Goes to College | College Girl | Wallace Beery played Sweedie in a series of shorts Essanay Film |

[8] |

| 1915 | The Romance of an American Duchess | Minor Role | Uncredited Essanay Film |

[124] |

| 1915 | The Broken Pledge | Gloria | Essanay Film | [6] |

| 1916 | A Dash of Courage | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[125] | |

| 1916 | Hearts and Sparks | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] | |

| 1916 | A Social Cub | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] | |

| 1916 | The Danger Girl | Reggie's madcap sister | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[126] |

| 1916 | Haystacks and Steeples | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] | |

| 1916 | The Nick of Time Baby | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] | |

| 1917 | Teddy at the Throttle | Gloria Dawn, His Sweetheart | Uncredited with Bobby Vernon Keystone/Triangle directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] |

| 1917 | Baseball Madness | Victor Film/Universal | [127] | |

| 1917 | Dangers of a Bride | Keystone/Triangle directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] | |

| 1917 | Whose Baby? | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] | |

| 1917 | The Sultan's Wife | Gloria | Keystone/Triangle with Bobby Vernon directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[6] |

| 1917 | The Pullman Bride | The Girl | Paramount-Mack Sennett directed by Clarence G. Badger |

[128] |

| 1922 | A Trip to Paramountown | Herself | Paramount | [129] |

Features

| Year | Title | Role | Notes Studio/Distributor |

Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918 | Society for Sale | Phylis Clyne | Triangle Film Corporation | [130] |

| 1918 | Her Decision | Phyllis Dunbar | Triangle Film Corporation directed by Jack Conway |

[131] |

| 1918 | You Can't Believe Everything | Patricia Reynolds | Triangle Film Corporation directed by Jack Conway |

[13] |

| 1918 | Station Content | Kitty Manning | Triangle Film Corporation directed by Arthur Hoyt |

[13] |

| 1918 | Everywoman's Husband | Edith Emerson | Triangle Film Corporation directed by Gilbert P. Hamilton |

[13] |

| 1918 | Shifting Sands | Marcia Grey | Triangle Film Corporation directed by Albert Parker |

[132] |

| 1918 | The Secret Code | Sally Carter Rand | Triangle Film Corporation directed by Albert Parker |

[13] |

| 1918 | Wife or Country | Sylvia Hamilton | Triangle Film Corporation directed by E. Mason Hopper |

[13] |

| 1919 | Don't Change Your Husband | Leila Porter | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Cecil B. DeMille |

[132] |

| 1919 | For Better, for Worse | Sylvia Norcross | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Cecil B. DeMille |

[13] |

| 1919 | Male and Female | Lady Mary Lasenby | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Cecil B. DeMille |

[133] |

| 1920 | Why Change Your Wife? | Beth Gordon | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Cecil B. DeMille |

[133] |

| 1920 | Something to Think About | Ruth Anderson | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Cecil B. DeMille |

[133] |

| 1921 | The Affairs of Anatol | Vivian Spencer – Anatol's Wife | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Cecil B. DeMille |

[133][134] |

| 1921 | The Great Moment | Nada Pelham/Nadine Pelham | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[133] |

| 1921 | Under the Lash | Deborah Krillet | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[135] |

| 1921 | Don't Tell Everything | Marian Westover | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[136] |

| 1922 | Her Husband's Trademark | Lois Miller | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[136] |

| 1922 | Her Gilded Cage | Suzanne Ornoff | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[136] |

| 1922 | Beyond the Rocks | Theodora Fitzgerald | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[136] |

| 1922 | The Impossible Mrs. Bellew | Betty Bellew | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[136] |

| 1922 | My American Wife | Natalie Chester | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[137] |

| 1923 | Prodigal Daughters | Swifty Forbes | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[138] |

| 1923 | Bluebeard's 8th Wife | Mona deBriac | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sam Wood |

[138] |

| 1923 | Hollywood | Cameo role | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount | [139] |

| 1923 | Zaza | Zaza | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Allan Dwan |

[138] |

| 1924 | The Humming Bird | Toinette | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Sidney Olcott |

[138] |

| 1924 | A Society Scandal | Marjorie Colbert | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Allan Dwan |

[138] |

| 1924 | Manhandled | Tessie McGuire | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Allan Dwan |

[138] |

| 1924 | Her Love Story | Princess Marie | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Allan Dwan |

[140] |

| 1924 | Wages of Virtue | Carmelita | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Allan Dwan |

[140] |

| 1925 | Madame Sans-Gêne | Madame Sans-Gêne | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Léonce Perret |

[140] |

| 1925 | The Coast of Folly | Joyce Gathway/Nadine Gathway | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Allan Dwan |

[140] |

| 1925 | Stage Struck | Jennie Hagen | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Allan Dwan |

[140] |

| 1926 | The Untamed Lady | St. Clair Van Tassel | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Frank Tuttle |

[141] |

| 1926 | Fine Manners | Orchid Murphy | Famous Players-Lasky/Paramount directed by Richard Rosson |

[141] |

| 1927 | The Love of Sunya | Sunya Ashling | Swanson Producing Corporation/United Artists directed by Albert Parker |

[141] |

| 1928 | Sadie Thompson | Sadie Thompson | Gloria Swanson Productions/United Artists directed by Raoul Walsh |

[141] |

| 1928 | Queen Kelly | Kitty Kelly/Queen Kelly | Joseph P. Kennedy/United Artists directed by Erich von Stroheim |

[141] |

| 1929 | The Trespasser | Marion Donnell | Gloria Productions/United Artists directed by Edmund Goulding Released in two versions, one silent, and the other with sound |

[39] |

| 1930 | What a Widow! | Tamarind Brook | Gloria Productions/United Artists directed by Allan Dwan |

[142] |

| 1931 | Indiscreet | Geraldine "Gerry" Trent | Feature Productions, Inc. A DeSylva, Brown & Henderson Production directed by Leo McCarey |

[142] |

| 1931 | Tonight or Never | Nella Vago | Feature Productions, Inc./United Artists directed by Mervyn LeRoy |

[142] |

| 1933 | Perfect Understanding | Judy Rogers | Gloria Swanson British Productions, Ltd./United Artists directed by Cyril Gardner |

[143] |

| 1934 | Music in the Air | Frieda Hotzfelt | Erich Pommer Productions/Fox Film directed by Joe May |

[144] |

| 1941 | Father Takes a Wife | Leslie Collier Osborne | Marcus Lee/RKO Radio Pictures, Inc. directed by William Dorfman |

[144] |

| 1950 | Sunset Boulevard | Norma Desmond | Charles Brackett/Paramount directed by Billy Wilder |

[144] |

| 1952 | Three for Bedroom "C" | Ann Haven/costume designer | Brenco Pictures Corporation/Warner Bros. directed by Milton H. Bren |

[145] |

| 1956 | Nero's Weekend (aka Nero's Mistress) | Agrippina | Les Films Marceau and Titanus/Manhattan Films International directed by Steno |

[57] |

| 1974 | Airport 1975 | Herself | Universal Pictures directed by Jack Smight |

[57] |

Television

| Year | Title | Role | Notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948 | The Gloria Swanson Hour | Swanson as herself | Variety show | [46] |

| 1950 | The Peter Lind Hayes Show | Swanson as herself | Episode #1.1 sitcom show |

[146] |

| 1953 | Hollywood Opening Night | Episode: "The Pattern" | [147] | |

| 1954–1955 | Crown Theatre with Gloria Swanson | Hostess | 25 episodes | [148] |

| 1957 | The Steve Allen Show | Norma Desmond | Episode #3.8 | [149] |

| 1961 | Straightaway | Lorraine Carrington | Episode: "A Toast to Yesterday" | [150] |

| 1963 | Dr. Kildare | Julia Colton | Episode: "The Good Luck Charm" | [59] |

| 1963–1964 | Burke's Law | Various roles | 2 episodes | [59] |

| 1964 | Kraft Suspense Theatre | Mrs. Charlotte Heaton | Segment: "Who Is Jennifer?" | [59] |

| 1964 | The Alfred Hitchcock Hour | Mrs. Daniels | Episode: "Behind the Locked Door" | [59] |

| 1965 | My Three Sons | Margaret McSterling | Episode: "The Fountain of Youth" | [59] |

| 1965 | Ben Casey | Victoria Hoffman | Episode: "Minus That Rusty Old Hacksaw" | [59] |

| 1966 | The Beverly Hillbillies | Herself | Episode: "The Gloria Swanson Story" | [59] |

| 1972 | The Eternal Tramp Special | Narrator | aka Chaplinesque, My Life and Hard Times | [151] |

| 1973 | The Carol Burnett Show | Herself | Episode #7.3 | [66] |

| 1974 | Killer Bees | Madame Maria von Bohlen | Television movie | [152] |

| 1974 | The Great Debate | Herself | Canadian interview show with James Bawden | [153] |

| 1980 | Hollywood | Herself | Television documentary | [154] |

Awards and nominations

| Year | Award | Result | Category | Film or series | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1929 | Academy Award | Nominated | Best Actress | Sadie Thompson | [30] |

| 1931 | The Trespasser | [38] | |||

| 1951 | Sunset Boulevard | [155] | |||

| 1951 | Golden Globe Award | Won | Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama | Sunset Boulevard | [156] |

| 1964 | Nominated | Best TV Star – Female | Burke's Law | [59] | |

| 1951 | Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists | Won | Best Actress – Foreign Film (Migliore Attrice Straniera) | Sunset Boulevard | [157] |

| 1951 | Jussi Award | Won | Best Foreign Actress | Sunset Boulevard | |

| 1950 | National Board of Review of Motion Pictures | Won | Best Actress | Sunset Boulevard | [158] |

| 1980 | Career Achievement Award | [159] | |||

| 1975 | Saturn Award | Won | Special Award | [160] |

Notes

- Quirk 1984, p. 256.

- Harzig & Matovic 2018, p. 283.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 6–8.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 9–11.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 11–12.

- "Gloria Swanson". silenthollywood.com. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 12–13.

- Welsch 2013, p. 18.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 20–3.

- Shearer 2013, p. 30.

- Birchard 2009, pp. 135–6.

- Birchard 2009, p. 138.

- Welsch 2013, p. 439.

- Welsch 2013, p. 58.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 439–40.

- "Beyond the Rocks". catalog.afi.com. AFI. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 93–4.

- "Gloria Swanson marries Marquis De la Flaise". Des Moines Tribune. January 28, 1925. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 443–4.

- Balio 2009, pp. 57–8.

- Welsch 2013, p. 169.

- "Subscribed Stock". www.money-zine.com. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 174–9.

- Balio 2009, pp. 82–3–8.

- Moss 2011, p. 100.

- Welsch 2013, p. 183.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 184–5.

- Moss 2011, pp. 101–2.

- Moss 2011, p. 103.

- "The 1st Academy Awards | 1929". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 201.

- Welsch 2013, p. 205.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 205–08, 213.

- Welsch 2013, p. 209.

- Lennig 2000, p. 275.

- "Queen Kelly". catalog.afi.com. AFI. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Lennig 2000, pp. 278, 288.

- "The 3rd Academy Awards | 1931". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 444–45.

- "The Widow". catalog.afi.com. AFI. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Listen In on the DODGE HOUR". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. March 29, 1928. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Hershfield 2000, p. 17.

- Balio 2009, p. 84.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 282–86.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 303–4.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 315–7.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 349–507.

- Phillips 2010, pp. 109, 112.

- Phillips 2010, p. 113.

- Phillips 2010, p. 115.

- Phillips 2010, p. 117.

- Willinds, David (November 30, 2018). "Beyond The Frame: Sunset Boulevard –". ascmag.com. The American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Phillips 2010, p. 118.

- "The 23rd Academy Awards 1951". Oscars.org. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Phillips 2010, p. 343.

- "Gold Coast – Suzy". The Miami News. June 24, 1952. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 447.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 347–48.

- Welsch 2013, p. 358.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 346, 354–55, 381.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 358, 367.

- Welsch 2013, p. 305.

- Gerard, Jeremy (January 15, 1988). "Harold Kennedy, Producer, Dies". The New York Times. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 308.

- Fitz Henry, Charlotte (August 20, 1944). "La Swanson Likes the Stage". The Evening Star. p. 41, col. 6. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 377–78.

- "William F. Dufty, 86; Wrote 'Lady Sings the Blues' and 'Sugar Blues'". Los Angeles Times. July 4, 2002.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 43, 366.

- Shearer 2013, p. 309.

- "Gloria Swanson's Glamor Never Fades". The Palm Beach Post. November 8, 1975. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 386.

- Welsch 2013, p. 389.

- Syman 2010, pp. 188–190.

- ""The Washington Merry-Go-Round", Drew Pearson column, May 14, 1964" (PDF). dspace.wrlc.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- Shearer 2013, p. 45.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 25–30, 66.

- Welsch 2013, p. 143.

- Welsch 2013, p. 66.

- Welsch 2013, p. 67.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 106, 111,158, 248, 274, 303, 379.

- Welsch 2013, p. 112.

- Welsch 2013, p. 114.

- "Film Producer Divorces Gloria Swanson; Says Star Deserted Him". Hawaii Tribune-Herald. September 20, 1923. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 355, 378–09.

- Welsch 2013, p. 138.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 144–48, 154–55,164, 238, 273, 85.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 299–300.

- Welsch 2013, p. 301.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 258–62.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 271–8.

- "Miss Swanson Divorces Her 4th Husband". The Tampa Tribune. November 8, 1934. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 281–2.

- Lee, Sonia (April 1935). "Scared of Spring". Picture Play Magazine. Vol. 42. p. 70. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

Hollywood is wondering if Gloria Swanson, once free of Michael Farmer, will make Herbert husband Number Five

- Peak, Mayme Ober (January 13, 1935). "To Be Called Sauve Gets on My Nerves". Daily Boston Globe. p. B5.

Now the Marshalls are separated by more than an ocean and continent. Since their separation, gossip has romantically linked the names of Gloria Swanson and Herbert Marshall. They are constantly seen together.

- "Film Writer Socks Actor in Row Over Gloria Swanson; Foes Tell Different Versions of How It All Happened". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. September 25, 1934. p. 1. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

...Swanson, whose name has been linked romantically with Mr. Marshall's prior to and since her separation from Michael Farmer. Mr. Marshall is likewise separated from Edna Best, English actress.

- Welsch 2013, p. 298.

- "Gloria Swanson Tells Davey's Drinking Habit". The Los Angeles Times. January 8, 1946. Retrieved May 27, 2010.

- "Memorial Shares Estate". Reno Gazette-Journal. October 17, 1949. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 311–14.

- Sugar Blues, 1975, Chilton, pp. 1–2

- Vanity Fair, November 2001, "John Lennon—The Collected Interviews: 1973–80" by Lisa Robinson

- "William F. Dufty, 86; Wrote 'Lady Sings the Blues' and 'Sugar Blues'". Los Angeles Times. July 4, 2002.

- "Swanson produced many draft versions of her autobiography over many years. There are holographs [handwritten manuscripts] as well as typescripts, notes, and lists, many annotated in her hand. I have referred to these in the notes as 'GS manuscript,' indicating when relevant her efforts at revision or deletion." Welsch 2013, p. 396

- Shearer 2013, p. 368.

- "Show Business" The Milwaukee Journal, October 1, 1980.

- Flint, Peter B. (April 5, 1983). "Gloria Swanson Dies. 20's Film Idol". New York Times. p. A1.

Gloria Swanson, a symbol of enduring glamour who was perhaps the most glittering goddess of Hollywood's golden youth in 1920s, died of a heart ailment yesterday in New York Hospital. She was 84 years old. The actress entered the hospital two weeks ago after suffering what friends said was a mild heart attack...

- Associated Press (April 5, 1983). "Gloria Swanson Dies". Herald-Journal. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

Gloria Swanson, the quintessential glamour girl who reigned in Hollywood's golden age died in her sleep at New York Hospital early Monday. ...

- Donnelley, Paul (2003). Fade to Black: A Book of Movie Obituaries. Omnibus. p. 887. ISBN 0-7119-9512-5.

- "Gloria Swanson | Hollywood Walk of Fame". walkoffame.com.

- "Eastman House Again Honors Gloria Swanson". Democrat and Chronicle. May 13, 1966. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 382.

- "An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center". University Texas Website.

- "Cotton Club". catalog.afi.com. AFI. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Shales, Tom (February 17, 1990). "TV PREVIEW". Washington Post. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Brennan, Patricia (May 5, 1991). "'WHITE HOT' THE UNSOLVED MURDER OF THELMA TODD". Washington Post. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Carbone, Gina (October 26, 2008). "Jon Hamm is mad funny! 'Mad Men' hero hams it up on SNL". seacoastonline.com. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Return to Babylon". cinema.usc.edu. USC Cinematic Arts | School of Cinematic Arts Events. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "A Goose for the Gander". IBDB. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Bathsheba". IBDB. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Twentieth Century". IBDB. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Nina". IBDB. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Butterflies Are Free". IBDB. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 14.

- Welsch 2013, p. 15.

- Welsch 2013, p. 22.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 24,36,355.

- Welsch 2013, p. 399n36.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 34–35.

- "Trip to Paramountown is Stellar Traffic Jam". The Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Society for Sale". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 438.

- Welsch 2013, p. 39.

- Welsch 2013, p. 440.

- Birchard 2009, p. 162.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 440–41.

- Welsch 2013, p. 441.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 441–42.

- Welsch 2013, p. 442.

- "Hollywood". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- Welsch 2013, p. 443.

- Welsch 2013, p. 444.

- Welsch 2013, p. 445.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 445–46.

- Welsch 2013, p. 446.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 446–47.

- "Gloria Swanson on Peter and Mary TV show". The Central New Jersey Home News. November 27, 1950.

- "Gloria Swanson to Do Live Dramatic TV Show". The Los Angeles Times. February 4, 1953.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 347–348.

- Welsch 2013, p. 359.

- "Straightaway – Gloria Swanson portrays an aging movie queen". The Philadelphia Inquirer. December 15, 1961.

- "The Eternal Tramp Special". The Morning Call. September 24, 1972.

- Welsch 2013, pp. 375–76.

- Bawden & Miller 2016, pp. 14–25.

- "Hollywood, Gloria Swanson and Rudolph Valentino". Detroit Free Press. July 10, 1981. p. 23.

- "The 23rd Academy Awards | 1951". Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

- "Gloria Swanson, Ferrer Awarded Golden Globes". Green Bay Press-Gazette. March 1, 1951. p. 6. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Film Festival in Punta Del Este, Uruguay". The News and Observer. March 12, 1951. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Gloria Swanson Rated Year's Best Actress". The Gazette. December 21, 1950. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Gloria Swanson career achievement award 1980". The News-Messenger. December 24, 1980. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "The Saturn Awards History: Past Honorees". www.saturnawards.org. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

Bibliogaphy

- Balio, Tino (2009). United Artists, Volume 1, 1919–1950: The Company Built by the Stars. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-23003-6.

- Bawden, James; Miller, Ron (2016). "Gloria Swanson". Conversations with Classic Film Stars: Interviews from Hollywood's Golden Era. The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 14–26. ISBN 978-0-8131-6712-1.

- Birchard, Robert S. S. (2009). Cecil B. DeMille's Hollywood. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2636-4.

- Harzig, Christiane; Matovic, Margareta, eds. (2018). "Embracing a Middle-Class Life: Swedish-American Women in Lake View". Peasant Maids, City Women: From the European Countryside to Urban America. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-2554-8.

- Hershfield, Joanne (2000). Invention Of Dolores Del Rio. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5282-2.

- Lennig, Arthur (2000). Stroheim. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-7125-8.

- Moss, Marilyn (2011). "Pre-Code Walsh". Raoul Walsh: The True Adventures of Hollywood's Legendary Director. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3394-2.

- Phillips, Gene (2010). Some Like It Wilder: The Life and Controversial Films of Billy Wilder. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-7367-2.

- Quirk, Lawrence J. (1984). The Films of Gloria Swanson. Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-0874-4.

- Shearer, Stephen Michael (2013). Gloria Swanson : the Ultimate Star. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-1-250-00155-9.

- Syman, Stefanie (2010). The Subtle Body: the Story of Yoga in America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-53284-0. OCLC 456171421.

- Welsch, Tricia (2013). Gloria Swanson: Ready for Her Close-Up. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-62103-991-4.

Further reading

- Card, James (1994). Seductive Cinema: The Art of Silent Film (paperback reprint). University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-3390-8.

- Hudson, Richard (1970). Gloria Swanson. Castle Books. LCCN 75-88280.

- Kobal, John (1985). People Will Talk. Knopf, New York. Especially Introduction and Chapter 1. ISBN 0-394-53660-6.

- Staggs, Sam (2003). Close-up on Sunset Boulevard: Billy Wilder, Norma Desmond, and the Dark Hollywood Dream. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-27453-X.

- Tapert, Annette (1998). The Power of Glamour. Crown Publishers, Inc. Introduction and Chapter 1. ISBN 0-517-70376-9.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gloria Swanson |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gloria Swanson. |

General

- Gloria Swanson on IMDb

- Gloria Swanson at the TCM Movie Database

- Gloria Swanson at the Women Film Pioneers Project

- Glorious Gloria Swanson – Tribute site

- Gloria Swanson's papers at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- Gloria Swanson photographs and bibliography

Interviews

- Gloria Swanson, video of The Mike Wallace Interview, April 28, 1957

- Gloria Swanson, interview on Dick Cavette Show on YouTube, August 3, 1970

.jpg)