IBM Personal Computer

The IBM Personal Computer, commonly known as the IBM PC, is the original version of the IBM PC compatible hardware platform. It is IBM model number 5150 and was introduced on August 12, 1981. It was created by a team of engineers and designers under the direction of Don Estridge in Boca Raton, Florida.

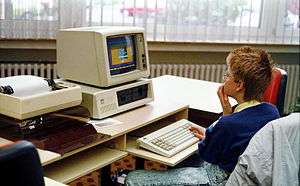

IBM Personal Computer with IBM CGA monitor (model 5153), IBM PC keyboard, IBM 5152 printer and paper stand. (1988) | |

| Manufacturer | IBM |

|---|---|

| Type | Personal Computer |

| Generation | First generation |

| Release date | August 12, 1981 |

| Introductory price | Starting at US$1,565 (equivalent to $4,401 in 2019) |

| Discontinued | April 2, 1987 |

| Operating system |

|

| CPU | Intel 8088 @ 4.77 MHz |

| Memory | 16 kB – 640 kB |

| Sound | PC speaker 1-channel square-wave/1-bit digital (PWM-capable) |

| Predecessor | IBM System/23 Datamaster |

| Successor | |

The generic term "personal computer" ("PC") was in use years before 1981, applied as early as 1972 to the Xerox PARC's Alto, but the term "PC" came to mean more specifically a desktop microcomputer compatible with IBM's Personal Computer branded products. The machine was based on open architecture, and third-party suppliers sprang up to provide peripheral devices, expansion cards, and software. IBM had a substantial influence on the personal computer market in standardizing a platform for personal computers, and "IBM compatible" became an important criterion for sales growth. Only the Apple Macintosh family kept a significant share of the microcomputer market after the 1980s without compatibility to the IBM personal computer.

History

Rumors

a company whose name is synonymous with computers

— The New York Times on IBM, 1981[1]

International Business Machines (IBM) had a 62% share of the mainframe computer market in the early 1980s.[2] Its slow entry into the minicomputer market in the 1960s, however, let new rivals like Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) and others earn billions in revenue.[1]

IBM did not want to repeat the mistake with personal computers.[1] In the late 1970s, the new industry was dominated by the Commodore PET, Atari 8-bit family, Apple II series, Tandy Corporation's TRS-80, and various CP/M machines.[3] The microcomputer market was large enough for IBM's attention, with $150 million in sales by 1979 and projected annual growth of more than 40% in the early 1980s. Other large technology companies had entered it, such as Hewlett-Packard (HP), Texas Instruments (TI), and Data General, and some large IBM customers were buying Apples.[4][5][6][7] IBM did not want a personal computer with another company's logo on mainframe customers' desks,[8] so introducing its own was both an experiment in a new market and a defense against rivals.[9][10]

In 1980 and 1981, rumors spread of an IBM personal computer, perhaps a miniaturized version of the IBM System/370,[11] while Matsushita acknowledged that it had discussed with IBM the possibility of manufacturing a personal computer for the American company.[12] The Japanese project was a Zilog Z80-based computer codenamed "Go"[13] but ended before the 1981 release of the American-designed IBM PC codenamed "Chess", and two simultaneous projects confused rumors about the forthcoming product.[14]

Competitors

Whether IBM had waited too long to enter an industry in which Tandy, Atari and others were already successful was unclear.[15][5][16] Data General and TI's small computers were not very successful,[6] but observers expected AT&T to soon enter the computer industry, and other large companies such as Exxon, Montgomery Ward, Pentel, and Sony were designing their own microcomputers.[17] Xerox quickly produced the 820 to introduce a personal computer before IBM,[18] becoming the second Fortune 500 company after Tandy to do so, and had its Xerox PARC laboratory's sophisticated technology.[19]

An observer stated that "IBM bringing out a personal computer would be like teaching an elephant to tap dance".[20] Successful microcomputer company Vector Graphic's fiscal 1980 revenue was $12 million.[6] A single IBM computer in the early 1960s cost as much as $9 million, occupied 1⁄4 acre (1,000 m2) of air-conditioned space, and had a staff of 60 people;[20] in 1980 its least-expensive computer, the 5120, still cost about $13,500.[21] The "Colossus of Armonk" only sold through its own sales force and had no experience with resellers or retail stores.[22][23][7][24]

Another observer claimed that IBM made decisions so slowly that, when tested, "what they found is that it would take at least nine months to ship an empty box",[25] and an employee complained that "IBM has more committees than the U.S. Government".[26] As with other large computer companies, its new products typically required about four to five years for development.[6][27][28][22] While IBM traditionally let others pioneer a new market—it released a commercial computer a year after Remington Rand's UNIVAC in 1951, but within five years had 85% of the market[26]—the personal-computer development and pricing cycles were much faster than for mainframes, with products designed in a few months and obsolete quickly.[6][5][29]

Many in the microcomputer industry expected that the personal computer would be, Bill Gates of Microsoft recalled, "the overthrow of IBM".[30] They resented the company's power and wealth, and disliked the perception that an industry founded by startups needed a latecomer so staid that it had a strict dress code and employee songbook, and prohibited salesmen with client visits in the afternoon from drinking alcohol at lunch.[31][26][25] The potential importance to microcomputers of a company so prestigious, that a popular saying in American companies stated "No one ever got fired for buying IBM", was nonetheless clear.[14][32][25][33] InfoWorld, which described itself as "The Newsweekly for Microcomputer Users", stated that "for my grandmother, and for millions of people like her, IBM and computer are synonymous".[34] Byte ("The Small Systems Journal") stated in an editorial[14] just before the announcement of the IBM PC:

Rumors abound about personal computers to come from giants such as Digital Equipment Corporation and the General Electric Company. But there is no contest. IBM's new personal computer ... is far and away the media star, not because of its features, but because it exists at all. When the number eight company in the Fortune 500 enters the field, that is news ... The influence of a personal computer made by a company whose name has literally come to mean "computer" to most of the world is hard to contemplate.

The editorial acknowledged that "some factions in our industry have looked upon IBM as the 'enemy'", but concluded with optimism: "I want to see personal computing take a giant step."[14]

Predecessors

Desktop sized programmable calculators by HP had evolved into the HP 9830 BASIC language computer by 1972. In 1972–1973 a team led by Dr. Paul Friedl at the IBM Los Gatos Scientific Center developed a portable computer prototype called SCAMP (Special Computer APL Machine Portable) based on the IBM PALM processor with a Philips compact cassette drive, small CRT, and full-function keyboard. SCAMP emulates the IBM 1130r to run APL\1130.[35] In 1973 APL was generally available only on mainframe computers, and most desktop sized microcomputers such as the Wang 2200 or HP 9800 offered only BASIC. Because it was the first to emulate APL\1130 performance on a portable, single-user computer, PC Magazine in 1983 designated SCAMP a "revolutionary concept" and "the world's first personal computer".[35][36] The prototype is in the Smithsonian Institution. A non-working industrial design model was also created in 1973 by industrial designer Tom Hardy illustrating how the SCAMP engineering prototype could be transformed into a usable product design for the marketplace. This design model was requested by IBM executive Bill Lowe to complement the engineering prototype in his early efforts to demonstrate the viability of creating a single-user computer.[37]

Successful demonstrations of the 1973 SCAMP prototype led to the IBM 5100 portable microcomputer in 1975. In the late 1960s such a machine would have been nearly as large as two desks and would have weighed about half a ton.[35] The 5100 is a complete computer system programmable in BASIC or APL, with a small built-in CRT monitor, keyboard, and tape drive for data storage. It was also very expensive, up to US$20,000; the computer was designed for professional and scientific customers, not business users or hobbyists.[38] BYTE in 1975 announced the 5100 with the headline "Welcome, IBM, to personal computing",[39] but PC Magazine in 1984 described 5100s as "little mainframes" and stated that "as personal computers, these machines were dismal failures ... the antithesis of user-friendly", with no IBM support for third-party software.[7] Despite news reports that the PC was the first IBM product without a model number, it was designated as the IBM 5150, putting it in the "5100" series[40] though its architecture is not descended from the IBM 5100. Later models followed in the trend: For example, the IBM Portable Personal Computer, PC/XT, and PC AT are IBM machine types 5155, 5160, and 5170, respectively.[41]

Following SCAMP, the IBM Boca Raton, Florida Laboratory created several single-user computer design concepts to support Lowe's ongoing effort to convince IBM there was a strategic opportunity in the personal computer business. A selection of these early IBM design concepts created by Hardy is highlighted in the book DELETE: A Design History of Computer Vapourware. One such concept in 1977, code-named Aquarius, is a working prototype utilizing advanced bubble memory cartridges. While this design is more powerful and smaller than Apple II launched the same year, the advanced bubble technology was deemed unstable and not ready for mass production.[37]

Project Chess

Some employees opposed IBM entering the market.[42] One said, "Why on earth would you care about the personal computer? It has nothing at all to do with office automation".[43] The company considered personal computer designs but had determined that IBM was unable to build a personal computer profitably.[22][5][37] Walden C. Rhines of TI met with a Boca Raton group in the late 1970s considering the TMS9900 16-bit microprocessor for a secret project. He wrote, "We wouldn’t know until 1981 just what we had lost" by not being chosen.[44]

IBM President John Opel was not among those skeptical of personal computers. He and CEO Frank Cary had created more than a dozen semi-autonomous "Independent Business Units" (IBU) to encourage innovation;[26][23][42][24] Fortune called them "how to start your own company without leaving IBM".[29] Lowe became the first head of the Entry Level Systems IBU in Boca Raton,[24] and his team researched the market. Computer dealers were very interested in selling an IBM product, but they told Lowe that the company could not design, sell, or service it as IBM had previously done. An IBM microcomputer, they said, must be composed of standard parts that store employees could repair.[16] Dealers disliked Apple's autocratic business practices, including a shortage of the Apple II while the company focused on the more sophisticated Apple III. They saw no alternative, however; IBM only sold directly so any IBM personal computer would only hurt them. Dealers doubted that IBM's traditional sales methods and bureaucracy would change.[7]

Schools in Broward County—near Boca Raton—purchased Apples, a consequence of IBM lacking a personal computer.[45] Atari proposed in 1980 that it act as original equipment manufacturer for an IBM microcomputer. Lowe was aware that the company needed to enter the market quickly,[46] so he met with Opel, Cary, and others on the Corporate Management Committee in 1980.[22][5] He demonstrated the proposal with an industrial design model by Hardy based on the Atari 800 platform, and suggested acquiring Atari "because we can't do this within the culture of IBM".[37][42][16]

Cary agreed about the culture, observing that IBM would need "four years and three hundred people" to develop its own personal computer; Lowe promised one in a year if done without traditional IBM methods.[25] Instead of acquiring Atari, the committee allowed him to form an independent group of employees called "the Dirty Dozen", led by engineer Bill Sydnes, and Lowe promised that they could design a prototype in 30 days. The crude prototype barely worked when Lowe demonstrated it in August, but he presented a detailed business plan which proposed that the new computer have an open architecture, use non-proprietary components and software, and be sold through retail stores, all contrary to IBM practice.[37][42][20][16] Lowe estimated sales of 220,000 computers over three years, more than IBM's entire installed base.[47]

The committee agreed that Lowe's approach was the most likely to succeed, and it approved turning the group into another IBU code named "Project Chess" to develop "Acorn", with unusually large funding to help achieve the goal of introducing the product within one year of the August demonstration. Don Estridge became the head of Chess.[48][24][42] Cary told the team to do whatever was necessary to develop an IBM personal computer quickly.[44][8][49] Key members included Sydnes,[42] Lewis Eggebrecht,[50][13] David Bradley,[51][52] Mark Dean,[53] and David O'Connor.[54] Many were already hobbyists who owned their own computers,[27] including Estridge, who had an Apple II.[55] Industrial designer Hardy was also assigned to the project.[56] The team received permission to expand to 150 people by the end of 1980, and more than 500 IBM employees called in one day asking to join.[5]

Open standards

IBM normally was vertically integrated, internally developing all important hardware and software[27] with only what was available in internal catalogs of IBM components,[47] and only purchasing parts like transformers and semiconductors.[57][49] The company's purchase of Rolm in 1984 was its first acquisition in 18 years.[58] IBM discouraged customers from purchasing compatible third-party products.[34]

IBM began using some outside components before the PC to save money and time,[47] but when designing it the company avoided vertical integration as much as possible; choosing, for example, to license Microsoft BASIC despite having a BASIC of its own for mainframes. (Estridge said that unlike IBM's own version "Microsoft BASIC had hundreds of thousands of users around the world. How are you going to argue with that?")[59] Although the company denied doing so, many observers concluded that IBM intentionally emulated Apple when designing the PC.[31][54][7] The many Apple II owners on the team influenced its decision to design the computer with an open architecture[50] and publish technical information so others could create software and expansion slot peripherals.[26][23]

Eggebrecht wanted to use the Motorola 68000, Gates recalled.[13] Rhines later said that it "was undoubtedly the hands-on winner" among 16-bit CPUs for an IBM microcomputer; big endian like other IBM computers, and more powerful than TMS9900 or Intel 8088. The 68000 was not production ready like the others, however; thus "Motorola, with its superior technology, lost the single most important design contest of the last 50 years", he said.[44] Project Go, from a rival division, planned to use an 8-bit CPU. Gates said that Project Chess also planned to do so until he convinced IBM to choose the 8088.[13] Although the company knew that it could not avoid competition from third-party software on proprietary hardware—Digital Research released CP/M-86 for the IBM Displaywriter, for example[15]—it considered using the IBM 801 RISC processor and its operating system, developed at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York. The 801 processor was more than an order of magnitude more powerful than the Intel 8088, and the operating system more advanced than the PC DOS 1.0 operating system from Microsoft. Ruling out an in-house solution made the team's job much easier and may have avoided a delay in the schedule, but the ultimate consequences of this decision for IBM were far-reaching.

IBM had recently developed the IBM System/23 Datamaster business microcomputer, which uses a processor and other chips from Intel; familiarity with them and the immediate availability of the 8088 was a reason for choosing it for the PC. The 62-pin expansion bus slots were designed to be similar to the Datamaster slots. Differences from the Datamaster include avoiding an all-in-one design while limiting the computer's size so that it fits on a standard desktop with the keyboard (also similar to the Datamaster's), and 5 1⁄4" disk drives instead of 8". Delays due to in-house development of the Datamaster software was a reason why IBM chose Microsoft BASIC—already available for the 8088—and published available technical information to encourage third-party developers.[52][24] IBM chose the 8088 over the similar but superior 8086 because Intel offered a better price on the former and could provide more units,[60] and the 8088's 8-bit bus reduced the cost of the rest of the computer.[52]

"Make or Buy"

Gates praised Eggebrecht for designing the 8088-based motherboard in 40 days, describing it as "one of the most phenomenal projects".[13] The IBU built a working prototype in four months[49] and made the first internal demonstration by January 1981.[22] The design for the computer was essentially complete by April 1981, when the manufacturing team took over the project.[20] IBM would not be able to make a profit if it were to use only its own hardware with Acorn; to save time and money, the IBU built the machine with commercial off-the-shelf parts from original equipment manufacturers whenever possible, with only final assembly occurring in Boca Raton at a plant Estridge designed. The IBU would decide whether it would be more economical to "Make or Buy" each manufacturing step.[5][57][23][49]

Various IBM divisions for the first time competed with outsiders to build parts of the new computer; a North Carolina IBM factory built the keyboard, the Endicott, New York factory had to lower its bid for printed circuit boards, and a Taiwanese company built the monitor.[5][42][48] The IBU chose an existing monitor from IBM Japan and an Epson printer. Because of the off-the-shelf parts only the system unit and keyboard has unique IBM industrial design elements. The IBM copyright appears in only the ROM BIOS and on the company logo,[56][23] and the company reportedly received no patents on the PC,[34] with outsiders manufacturing 90% of it.[57] Because the product would carry the IBM logo, the only corporate division the IBU could not bypass was the Quality Assurance Unit,[27][48] part of why IBM did not use the 68000.[44] A component manufacturer described the process of being selected as a supplier as rigorous and "absolutely amazing", with IBM inspectors even testing solder flux. They stayed after selection, monitoring and helping to improve the manufacturing process. IBM's size overwhelmed other companies; "a hundred IBM engineers" reportedly visited Mitel to meet with two of the latter's employees about a problem, according to The New York Times.[57]

Another aspect of IBM that did not change was secrecy;[45] employees at Yorktown knew nothing of Boca Raton's activities.[61] Those working on the project, within and outside of IBM, were under strict confidentiality agreements. When an individual mentioned in public on a Saturday that his company was working on software for a new IBM computer, IBM security appeared at the company on Monday to investigate the leak.[62] After an IBM official discovered printouts in a supplier's garbage, the former's company persuaded the latter to purchase a paper shredder. Management Science America did not know until after agreeing to buy Peachtree Software in 1981 that the latter was working on software for the PC.[63] Developers such as Software Arts received breadboard prototype computers[64] in soldered boxes lined with lead to block X-rays, and had to keep them in locked, windowless rooms;[65] to develop software, Microsoft emulated the PC on a DEC minicomputer and used the prototype for debugging.[24] After the PC's debut, IBM Boca Raton employees continued to decline to discuss their jobs in public. One writer compared the "silence" after asking one about his role at the company to "hit[ting] the wall at the Boston Marathon: the conversation is over".[45]

Debut

IBM is proud to announce a product you may have a personal interest in. It's a tool that could soon be on your desk, in your home or in your child's schoolroom. It can make a surprising difference in the way you work, learn or otherwise approach the complexities (and some of the simple pleasures) of living.

It's the computer we're making for you.

— IBM PC advertisement, 1982[66]

After developing it in 12 months—faster than any other hardware product in company history[49]—IBM announced the Personal Computer on August 12, 1981. Pricing started at US$1,565 (equivalent to $4,401 in 2019) for a configuration with 16K RAM, Color Graphics Adapter, and no disk drives. The company intentionally set prices for it and other configurations that were comparable to those of Apple and other rivals;[67][68][27][23][69][42][20] the Datamaster, announced two weeks earlier as the previous least-expensive IBM computer, cost $10,000.[1][8] What Dan Bricklin described as "pretty competitive" pricing surprised him and other Software Arts employees.[61] One analyst stated that IBM "has taken the gloves off",[2] while the company said "we suggest [the PC's price] invites comparison".[70]

BYTE described IBM as having "the strongest marketing organization in the world",[15] but the PC's marketing also differed from that of previous products. The company was aware of its strong corporate reputation among potential customers; an early advertisement began "Presenting the IBM of Personal Computers".[66][71][23] Estridge recalled that "The most important thing we learned was that how people reacted to a personal computer emotionally was almost more important than what they did with it".[49] Advertisements emphasized the novelty of an individual owning an IBM computer, describing "a product you may have a personal interest in"[66] and asking readers to think of "'My own IBM computer. Imagine that' ... it's yours. For your business, your project, your department, your class, your family and, indeed, for yourself".[72]

In addition to the existing corporate sales force IBM opened its own Product Center retail stores.[73] After studying Apple's successful distribution network, the company surprised the industry by selling through others for the first time, including ComputerLand and Sears Roebuck.[68][22][29][7][23][58] Because retail stores receive revenue from repairing computers and providing warranty service, IBM broke a 70-year tradition by permitting and training non-IBM service personnel to fix the PC.[5]

The Little Tramp

IBM considered Alan Alda, Beverly Sills, Kermit the Frog, and Billy Martin to be celebrity endorsers of the PC,[74] but chose Charlie Chaplin's The Little Tramp character for a series of advertisements based on Chaplin's films, played by Billy Scudder.[75][76] Chaplin's film Modern Times expressed his opposition to big business, mechanization, and technological efficiency, but the $36-million marketing campaign made Chaplin the (according to Creative Computing) "warm cuddly" mascot of one of the world's largest companies.[77][76][75][23][78]

Chaplin and his character became so widely associated with IBM that others used his bowler hat and cane to represent or satirize the company.[79][80][81][82][76] Chaplin's estate sued those who used the trademark without permission, yet PC Magazine's April 1983 issue had 12 advertisements which referred to the Little Tramp.[75]

Third-party products

Perhaps Chess's most unusual decision for IBM was to publish the PC's technical specifications, allowing outsiders to create products for it.[26][49] "We encourage third-party suppliers ... we are delighted to have them", the company stated.[34] Although the team began dogfooding before the PC's debut by managing business operations on prototypes,[49] and despite IBM's $5.3 billion R&D budget in 1982—larger than the total revenue of many competitors[26]—the company did not sell internally developed PC software until April 1984,[83] instead relying on already established software companies.[67][68] Microsoft, Personal Software, and Peachtree Software were among the developers of nine launch titles including EasyWriter and VisiCalc, all already available for other computers.[1] The company contacted Microsoft even before the official approval of Chess,[22] and it and others received cooperation that was, PC Magazine said, "unheard of" for IBM.[84] Such openness surprised observers;[54] BYTE called it "striking"[68] and "startling",[15] and one developer reported that "it's a very different IBM". Another said "They were very open and helpful about giving us all the technical information we needed. The feeling was so radically different—it's like stepping out into a warm breeze." He concluded, "After years of hassling—fighting the Not-Invented-Here attitude—we're the gods."[40]

Most other personal-computer companies did not disclose technical details.[71] Tandy hoped to monopolize sales of TRS-80 software and peripherals. Its RadioShack stores only sold Tandy products; third-party developers found selling their offerings difficult.[69] TI intentionally made developing third-party TI-99/4A software difficult,[85][86] even requiring a lockout chip in cartridges.[87] IBM itself kept its mainframe technology so secret that rivals were indicted for industrial espionage.[34] For the PC, however, IBM immediately released detailed information. The US$36 IBM PC Technical Reference Manual included complete circuit schematics, commented ROM BIOS source code, and other engineering and programming information for all of IBM's PC-related hardware, plus instructions on designing third-party peripherals.[71] It was so comprehensive that one reviewer suggested that the manual could serve as a university textbook,[88] and so clear that a developer claimed that he could design an expansion card without seeing the physical computer.[34]

IBM marketed the technical manual in full-page color print advertisements, stating that "our software story is still being written. Maybe by you".[89] Sydnes stated that "The definition of a personal computer is third-party hardware and software". Estridge said that IBM did not keep software development proprietary because it would have to "out-VisiCalc VisiCorp and out-Peachtree Peachtree—and you just can't do that".[54]

Another advertisement told developers that the company would consider publishing software for "Education. Entertainment. Personal finance. Data management. Self-improvement. Games. Communications. And yes, business."[90] Estridge explicitly invited small, "cottage" amateur and professional developers to create products[1][68] "with", he said, "our logo and our support".[91] IBM sold the PC at a large discount to employees, encouraged them to write software,[7] and distributed a catalog of inexpensive software written by individuals that might not otherwise appear in public.[92][93]

Reaction

The announcement by "a company whose name is synonymous with computers", the Times said, gave credibility to the new industry.[1] The press reported on most details of the PC before the official announcement; only IBM not providing internally developed software, including DOS (86-DOS) as the operating system, surprised observers.[67] BYTE was correct in predicting that an IBM personal computer would nonetheless receive much public attention. Its rapid development amazed observers,[27] as did the Colossus of Armonk selling as a launch title Microsoft Adventure (a video game that, its press release stated, brought "players into a fantasy world of caves and treasures");[1][61][94][7] the company even offered an optional joystick port.[68] Future Computing estimated that "IBM's Billion Dollar Baby" would have $2.3 billion in hardware sales by 1986.[95] David Bunnell, an editor at Osborne/McGraw-Hill, recalled that[54]

None of my associates wanted to talk about the Apple II or the Osborne I computer anymore, nor did they want to fantasize about writing the next super-selling program ... All they wanted to talk about was the IBM Personal Computer—what it was, its potential and limitations, and most of all, the impact IBM would have on the business of personal computing.

Within seven weeks Bunnell helped found PC Magazine,[96] the first periodical for the new computer.[71]

The industry awaited and feared IBM's announcement for months.[1] InfoWorld reported that "On the morning of the announcement, phone calls to IBM's competitors revealed that almost everyone was having an 'executive meeting' involving the high-level officials who might be in a position to publicly react to the IBM announcement". Claiming that the new IBM computer competed against rivals' products,[67] they were publicly skeptical about the PC. Adam Osborne said that unlike his Osborne I, "when you buy a computer from IBM, you buy a la carte. By the time you have a computer that does anything, it will cost more than an Apple. I don't think Apple has anything to worry about". Apple's Mike Markkula agreed that IBM's product was more expensive than the Apple II, and claimed that the Apple III "offers better performance". He denied that the IBM PC offered more memory, stating that his company could offer more than 128K "but frankly we don't know what anyone would do with that memory".[97] At Tandy, John Roach said "I don't think it's that significant";[98] Jon Shirley admitted that IBM had a "legendary service reputation" but claimed that the thousands of Radio Shack stores "can provide better service", while predicting that the IBM PC's "major market will be IBM addicts";[97] and Garland P. Asher said that he was "relieved that whatever they were going to do, they finally did it. I'm certainly relieved at the pricing".[1] Tandy could undersell a $3,000 IBM computer by $1,000, he stated.[70]

Many criticized the PC's design as outdated and not innovative, and believed that alleged weaknesses, such as the use of single-sided, single-density disks with less storage than the computer's RAM, and limited graphics capability (customers who wanted both color and high-quality text needed two graphics cards and two monitors), existed because the company was uncertain about the market and was experimenting before releasing a better computer.[97][99][16][98] (Estridge boasted, "Many ... said that there was nothing technologically new in this machine. That was the best news we could have had; we actually had done what we had set out to do".[59])

Although the Times said that IBM would "pose the stiffest challenge yet to Apple and to Tandy",[1] they and Commodore—together with more than 50% of the personal-computer market[70]—had many advantages. While IBM began with one microcomputer, little available hardware or software, and a couple of hundred dealers,[1][100] Radio Shack had sold more than 350,000 computers.[101] It had 14 million customers and 8,000 stores—more than McDonald's[102][69]—that only sold its broad range of computers and accessories. Apple had sold more than 250,000 computers and had five times as many dealers in the US as IBM and an established international distribution network. Hundreds of independent developers produced software and peripherals for Tandy and Apple computers; at least ten Apple databases and ten word processors were available, while the PC had no databases and one word processor.[103][101][100] Altos, Vector Graphic, Cromemco, and Zenith were among those making CP/M, InfoWorld said, "the small-computer operating system".[101]

Radio Shack and Apple hoped that an IBM personal computer would help grow the market.[1][67] Steve Jobs at Apple ordered a team to examine an IBM PC. After finding it unimpressive—Chris Espinosa called the computer "a half-assed, hackneyed attempt"—the company confidently purchased a full-page advertisement in The Wall Street Journal with the headline "Welcome, IBM. Seriously". Gates was at Apple headquarters the day of IBM's announcement and later said "They didn't seem to care. It took them a full year to realize what had happened".[104][26][105]

Success

The most important thing we learned was that how people reacted to a personal computer emotionally was almost more important than what they did with it. That was an entirely new lesson in computer design.

— Don Estridge, 1985[49]

The PC was immediately successful. PC Magazine later wrote that "IBM's biggest error was in underestimating the demand for the PC".[7] BYTE reported a rumor that more than 40,000 were ordered on the day of the announcement;[15] one dealer received 22 $1,000 deposits from customers although he could not promise a delivery date.[20] John Dvorak recalled that a dealer that day praised the computer as an "incredible winner, and IBM knows how to treat us — none of the Apple arrogance".[106] The company could have sold its entire projected first-year production to employees, and IBM customers that were reluctant to purchase Apples were glad to buy microcomputers from their traditional supplier.[7] The computer began shipping in October, ahead of schedule;[98] by then some referred to it simply as "the PC".[107]

BYTE estimated that 90% of the 40,000 first-day orders were from software developers.[15] By COMDEX in November Tecmar developed 20 products including memory expansion and expansion chassis,[108] surprising even IBM.[54] Jerry Pournelle reported after attending the West Coast Computer Faire in early 1982 that because IBM "encourages amateurs" with "documents that tell all", "an explosion of [third-party] hardware and software" was visible at the convention.[86] Many manufacturers of professional business application software, who had been planning/developing versions for the Apple II, promptly switched their efforts over to the IBM PC when it was announced. Often, these products needed the capacity and speed of a hard-disk. Although IBM did not offer a hard-disk option for almost two years following introduction of its PC, business sales were nonetheless catalyzed by the simultaneous availability of hard-disk subsystems, like those of Tallgrass Technologies which sold in ComputerLand stores alongside the IBM 5150 at the introduction in 1981.

One year after the PC's release, although IBM had sold fewer than 100,000 computers,[109] PC World counted 753 software packages for the PC—more than four times the number available for the Apple Macintosh one year after its 1984 release—including 422 applications and almost 200 utilities and languages.[109] InfoWorld reported that "most of the major software houses have been frantically adapting their programs to run on the PC", with new PC-specific developers composing "an entire subindustry that has formed around the PC's open system", which Dvorak described as a "de facto standard microcomputer".[34] The magazine estimated that "hundreds of tiny garage-shop operations" were in "bloodthirsty" competition to sell peripherals, with 30 to 40 companies in a price war for memory-expansion cards, for example.[110] PC Magazine renamed its planned "1001 Products to Use with Your IBM PC" special issue after the number of product listings it received exceeded the figure.[34] Tecmar and other companies that benefited from IBM's openness rapidly grew in size and importance, as did PC Magazine; within two years it expanded from 96 bimonthly to 800 monthly pages, including almost 500 pages of advertisements.[111][23]

Gates correctly predicted that IBM would sell "not far from 200,000" PCs in 1982;[28][8][26] by the end of the year it was selling one every minute of the business day.[33] The company estimated that 50 to 70% of PCs sold in retail stores went to the home,[112] and the publicity from selling a popular product to consumers caused IBM to, a spokesman said, "enter the world" by familiarizing them with the Colossus of Armonk. Although the PC only provided two to three percent of sales[5] the company found that demand exceeded its estimate by as much as 800%. Because its prices were based on forecasts of much lower volume—250,000 over five years, which would have made the PC a very successful IBM product—the PC became very profitable; at times the company sold almost that many computers per month.[42][52][24] Estridge said in 1983 that from October 1982 to March 1983 customer demand quadrupled, with production increasing three times in one year, and warned of a component shortage if demand continued to increase.[59] Many small suppliers' sales to IBM grew rapidly,[8] both pleasing their executives and causing them to worry about being overdependent on it. Miniscribe, for example, in 1983 received 61% of its hard drive orders from IBM; the company's stock price fell by more than one third in one day after IBM reduced orders in January 1984. Suppliers often found, however, that the prestige of having IBM as a customer led to additional sales elsewhere.[57]

By early 1983 the Times said "I.B.M.'s role in the personal computer world is beginning to resemble its central role in the mainframe computer business, in which I.B.M. is the sun around which everything else revolves". As "a de facto standard", the newspaper wrote, "Virtually every software company is giving first priority to writing programs for the I.B.M. machine".[8] Yankee Group estimated that year that ten new IBM PC-related products appeared every day.[9] In August the Chess IBU, with 4,000 employees, became the Entry Systems Division, which observers believed indicated that the PC was significantly important to IBM overall, and no longer an experiment.[9][42][24] In November the Associated Press stated that the PC "in two years [had] effectively set a new standard in desktop computers",[113] and The Economist said that IBM "set a standard that those who hope to compete will usually have to follow".[114]

The PC surpassed the Apple II in late 1983 as the best-selling personal computer[49] with more than 750,000 sold by the end of the year,[24] while DEC only sold 69,000 microcomputers in the first nine months despite offering three models for different markets.[115] IBM recruited the best Apple dealers while avoiding the grey market; by March 1983 770 separate resellers sold the PC in the US and Canada.[8] It was 65% of BusinessLand's revenue. Demand still so exceeded supply two years after its debut that, despite IBM shipping 40,000 PCs a month, dealers reportedly received 60% or less of their desired quantity;[116] some promoted Apples to reduce dependence.[8] Pournelle received the PC he paid for in early July 1983 on 1 November,[26][117] and IBM Boca Raton employees and neighbors had to wait five weeks to buy the computers assembled there.[45]

Domination

IBM's success ... clearly shows that 'me-too' technology is not a detriment to market acceptance and may in fact aid in market acceptance.

— Yankee Group, November 1983[9]

Yankee Group also stated that the PC had by 1983 "destroyed the market for some older machines" from companies like Vector Graphic, North Star, and Cromemco.[9] inCider wrote "This may be an Apple magazine, but let's not kid ourselves, IBM has devoured competitors like a cloud of locusts".[118] By February 1984 BYTE reported on "the phenomenal market acceptance of the IBM PC",[119] and by fall concluded that the company "has given the field its third major standard, after the Apple II and CP/M".[120] Rivals speculated that the government might again prosecute IBM for antitrust, and Ben Rosen claimed that the company's dominance "is having a chilling effect on new ventures, a fear factor".[121]

By that time, Apple was less welcoming of the rival that inCider stated had a "godlike" reputation.[118] The PC almost completely ended sales of the Apple III, the company's most comparable product,[8] but its focus on the III had delayed improvements to the II, and the sophisticated Lisa was unsuccessful in part because, unlike the II and the PC, Apple discouraged third-party developers. The head of a retail chain said "It appears that IBM had a better understanding of why the Apple II was successful than had Apple".[7] Jobs, after trying to recruit Estridge to become Apple's president,[105] admitted that in two years IBM had joined Apple as "the industry's two strongest competitors". He warned in a speech before previewing the forthcoming "1984" Super Bowl commercial: "It appears IBM wants it all ... Will Big Blue dominate the entire computer industry? The entire information age? Was George Orwell right about 1984?"[122]

IBM had $4 billion in annual PC revenue by 1984, more than twice that of Apple and as much as the sales of Apple, Commodore, HP, and Sperry combined,[123] and 6% of total revenue.[124] Most companies with mainframes used PCs with the larger computers. Customers having what some IBM executives called the "logo machine" on desks likely benefited mainframe sales and discouraged their purchasing non-IBM hardware;[8][114][125] they "prefer a single standard", The Economist said.[114] A 1983 study of corporate customers found that two thirds of large customers standardizing on one computer chose the PC, compared to 9% for Apple.[126] A 1985 Fortune survey found that 56% of American companies with personal computers used PCs, compared to Apple's 16%.[127]

Yankee Group wrote that the PC's success showed that "technological elegance and a leading price/performance position is almost irrelevant to market success".[9] IBM had defeated UNIVAC with an inferior mainframe computer,[26] and IBM's own documentation agreed with observers that described the PC as inferior to competitors' less-expensive products. The company generally did not compete on price; rather, the 1983 study found that customers preferred "IBM's hegemony" because of its support.[126] They wanted "vendor recognition, applications software availability (vendor and third-party), a reputation for product reliability and support, moderately competitive pricing, and an assurance that the vendor won't disappear in the impending personal computer market shakeout", Yankee Group wrote.[9]

In 1984, IBM introduced the PC/AT, unlike its predecessor the most sophisticated personal computer from any major company.[23][121][128] By 1985, the PC family had more than doubled Future Computing's 1986 revenue estimate, with more than 12,000 applications and 4,500 dealers and distributors worldwide.[129] The PC was similarly dominant in Europe, two years after release there.[125] In his 1985 obituary, The New York Times wrote that Estridge had led the "extraordinarily successful entry of the International Business Machines Corporation into the personal computer field". The Entry Systems Division had 10,000 employees and by itself would have been the world's third-largest computer company behind IBM and DEC,[49] with more revenue than IBM's minicomputer business despite its much later start. IBM was the only major company with significant minicomputer and microcomputer businesses;[129] rivals like DEC and Wang also released personal computers[9] but did not adjust to retail sales.[8][130]

Rumors of "lookalike", compatible computers, created without IBM's approval, began almost immediately after the IBM PC's release.[15][40] Other manufacturers soon reverse engineered the BIOS to produce their own non-infringing functional copies. Columbia Data Products introduced the first IBM-PC compatible computer in June 1982. In November 1982, Compaq Computer Corporation announced the Compaq Portable, the first portable IBM PC compatible. The first models were shipped in January 1983.

IBM PC as standard

The success of the IBM computer led other companies to develop IBM Compatibles, which in turn led to branding like diskettes being advertised as "IBM format". An IBM PC clone could be built with off-the-shelf parts, but the BIOS required some reverse engineering. Companies like Compaq, Phoenix Software Associates, American Megatrends, Award, and others achieved fully functional versions of the BIOS, allowing companies like Dell, Gateway and HP to manufacture PCs that worked like IBM's product. The IBM PC became the industry standard.

Third-party distribution

Because IBM had no retail experience, the retail chains ComputerLand and Sears Roebuck provided important knowledge of the marketplace.[131][23][48][7] They became the main outlets for the new product. More than 190 ComputerLand stores already existed, while Sears was in the process of creating a handful of in-store computer centers for sale of the new product. This guaranteed IBM widespread distribution across the U.S.

Targeting the new PC at the home market, Sears Roebuck sales failed to live up to expectations. This unfavorable outcome revealed that the strategy of targeting the office market was the key to higher sales.

Models

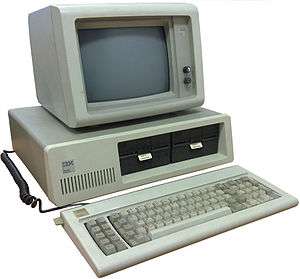

IBM 5150 PC with dual disk drives, an IBM 5151 monitor and an IBM model F keyboard |

| Model name | Model # | Introduced | Discontinued | CPU | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | 5150 | August 1981 | April 1987 | 8088 | Floppy disk or cassette system.[132] One or two internal floppy drives were optional. |

| XT | 5160 | March 1983 | April 1987 | 8088 | First IBM PC to come with an internal hard drive as standard. |

| XT/370 | 5160/588 | October 1983 | April 1987 | 8088 | 5160 with XT/370 Option Kit and 3277 Emulation Adapter |

| 3270 PC | 5271 | October 1983 | April 1987 | 8088 | With 3270 terminal emulation, 20 function key keyboard |

| PCjr | 4860 | November 1983 | March 1985 | 8088 | Floppy-based home computer, but also used ROM cartridges; infrared keyboard |

| Portable | 5155 | February 1984 | April 1986 | 8088 | Floppy-based portable |

| AT | 5170 | August 1984 | April 1987 | 80286 | Faster processor, faster system bus (6 MHz, later 8 MHz, vs 4.77 MHz), jumperless configuration, real-time clock |

| AT/370 | 5170/599 | October 1984 | April 1987 | 80286 | 5170 with AT/370 Option Kit and 3277 Emulation Adapter |

| 3270 AT | 5281 | June 1985[133] | April 1987 | 80286 | With 3270 terminal emulation |

| Convertible | 5140 | April 1986 | August 1989 | 80C88 | Microfloppy laptop portable |

| XT 286 | 5162 | September 1986 | April 1987 | 80286 | Slow hard disk, but zero wait state memory on the motherboard. This 6 MHz machine was actually faster than the 8 MHz ATs (when using planar memory) because of the zero wait states |

All IBM personal computers are software backwards-compatible with each other in general, but not every program will work in every machine. Some programs are time sensitive to a particular speed class. Older programs will not take advantage of newer higher-resolution and higher-color display standards, while some newer programs require newer display adapters. (Note that as the display adapter was an adapter card in all of these IBM models, newer display hardware could easily be, and often was, retrofitted to older models.) A few programs, typically very early ones, are written for and require a specific version of the IBM PC BIOS ROM. Most notably, BASICA which was dependent on the BIOS ROM had a sister program called GW-BASIC which supported more functions, was 100% backwards compatible and could run independently from the BIOS ROM.

Original PC

The CGA video card, with a suitable modulator, could use an NTSC television set or an RGBi monitor for display; IBM's RGBi monitor was their display model 5153. The other option that was offered by IBM was an MDA and their monochrome display model 5151. It was possible to install both an MDA and a CGA card and use both monitors concurrently[134] if supported by the application program. For example, AutoCAD, Lotus 1-2-3 and others allowed use of a CGA Monitor for graphics and a separate monochrome monitor for text menus. Some model 5150 PCs with CGA monitors and a printer port also included the MDA adapter by default, because IBM provided the MDA port and printer port on the same adapter card; it was in fact an MDA/printer port combo card.

Although cassette tape was originally envisioned by IBM as a low-budget storage alternative, the most commonly used medium was the floppy disk. The 5150 was available with one or two 5 1⁄4" floppy drives – with two drives the program disc(s) would be in drive A, while drive B would hold the disc(s) for working files; with one drive the user had to swap program and file discs into the single drive. For models without any drives or storage medium, IBM intended users to connect their own cassette recorder via the 5150's cassette socket. The cassette tape socket was physically the same DIN plug as the keyboard socket and next to it, but electrically completely different.

A hard disk drive could not be installed into the 5150's system unit without changing to a higher-rated power supply (although later drives with lower power consumption have been known to work with the standard 63.5 Watt unit). The "IBM 5161 Expansion Chassis" came with its own power supply and one 10 MB hard disk and allowed the installation of a second hard disk.[135] Without the expansion chassis perhaps one free slot remains after installing necessary cards,[136] as a working configuration requires that some of the slots be occupied by display, disk, and I/O adapters, as none of these were built into the 5150's motherboard; the only motherboard external connectors are the keyboard and cassette ports.The system unit has five expansion slots, and the expansion unit has eight; however, one of the system unit's slots and one of the expansion unit's slots have to be occupied by the Extender Card and Receiver Card, respectively, which are needed to connect the expansion unit to the system unit and make the expansion unit's other slots available, for a total of 11 slots.

The simple PC speaker sound hardware was also on board.

The original PC's maximum memory using IBM parts was 256 kB, achievable through the installation of 64 kB on the motherboard and three 64 kB expansion cards. The processor was an Intel 8088 running at 4.77 MHz, 4/3 the standard NTSC color burst frequency of 315/88 = 3.57954[lower-alpha 1] MHz. (In early units, the Intel 8088 used was a 1978 version, later were 1978/81/2 versions of the Intel chip; second-sourced AMDs were used after 1983). Some owners replaced the 8088 with an NEC V20 for a slight increase in processing speed and support for real mode 80186 instructions. The V20 gained its speed increase through the use of a hardware multiplier which the 8088 lacked. An Intel 8087 coprocessor could also be added for hardware floating-point arithmetic.

IBM sold the first IBM PCs in configurations with 16 or 64 kB of RAM preinstalled using either nine or thirty-six 16-kilobit DRAM chips. (The ninth bit was used for parity checking of memory.) In November 1982, the hardware was changed to allow the use of 64-Kbit chips (as opposed to the original 16-Kbit chips) - the same RAM configuration as the soon-to-be-released IBM XT. (64 kB in one bank, expandable to 256kB by populating the other three banks.)

Although the TV-compatible video board, cassette port and Federal Communications Commission Class B certification were all aimed at making it a home computer,[52] the original PC proved too expensive for the home market. At introduction, a PC with 64 kB of RAM and a single 5.25-inch floppy drive and monitor sold for US $3,005 (equivalent to $8,451 in 2019), while the cheapest configuration (US $1,565) that had no floppy drives, only 16 kB RAM, and no monitor (again, under the expectation that users would connect their existing TV sets and cassette recorders) proved too unattractive and low-spec, even for its time (cf. footnotes to the above IBM PC range table).[137][138] While the 5150 did not become a top selling home computer, its floppy-based configuration became an unexpectedly large success with businesses.

XT

The "IBM Personal Computer XT", IBM model 5160, was introduced two years after the PC and featured a 10 megabyte hard drive. It had eight expansion slots but the same processor and clock speed as the PC. The XT had no cassette jack, but still had the Cassette Basic interpreter in ROMs.

The XT could take 256 kB of memory on the main board (using 64 kbit DRAM); later models were expandable to 640 kB. The remaining 384 kilobytes of the 8088 address space (between 640 KB and 1 MB) were used for the BIOS ROM, adapter ROM and RAM space, including video RAM space. It was usually sold with a Monochrome Display Adapter (MDA) video card or a CGA video card.

The eight expansion slots were the same as the model 5150 but were spaced closer together. Although rare, a card designed for the 5150 could be wide enough to obstruct the adjacent slot in an XT.[139][140] Because of the spacing, an XT motherboard would not fit into a case designed for the PC motherboard, but the slots and peripheral cards were compatible. The XT expansion bus (later called "8-bit Industry Standard Architecture" (ISA) by competitors) was retained in the IBM AT, which added connectors for some slots to allow 16-bit transfers; 8-bit cards could be used in an AT.

XT/370

The "IBM Personal Computer XT/370" was an XT with three custom 8-bit cards: the processor card (370PC-P) contained a modified Motorola 68000 chip, microcoded to execute System/370 instructions, a second 68000 to handle bus arbitration and memory transfers, and a modified 8087 to emulate the S/370 floating point instructions. The second card (370PC-M) connected to the first and contained 512 kB of memory. The third card (PC3277-EM), was a 3270 terminal emulator necessary to install the system software for the VM/PC software to run the processors.

The computer booted into DOS, then ran the VM/PC Control Program.[141][142]

PCjr

The "IBM PCjr" was IBM's first attempt to enter the market for relatively inexpensive educational and home-use personal computers. The PCjr, IBM model number 4860, retained the IBM PC's 8088 CPU and BIOS interface for compatibility, but its cost and differences in the PCjr's architecture, as well as other design and implementation decisions (chief among these was the use of a "chiclet" keyboard, which was difficult to type with), eventually led to the PCjr, and the related IBM JX, being commercial failures.

Portable

The "IBM Portable Personal Computer" 5155 model 68 was an early portable computer developed by IBM after the success of Compaq's suitcase-size portable machine (the Compaq Portable). It was released in February 1984, and was eventually replaced by the IBM Convertible.

The Portable was an XT motherboard, transplanted into a Compaq-style luggable case. The system featured 256 kilobytes of memory (expandable to 512 KB), an added CGA card connected to an internal monochrome (amber) composite monitor, and one or two half-height 5.25" 360 KB floppy disk drives. Unlike the Compaq Portable, which used a dual-mode monitor and special display card, IBM used a stock CGA board and a composite monitor, which had lower resolution. It could however, display color if connected to an external monitor or television.

AT

The "IBM Personal Computer/AT" (model 5170), announced August 15, 1984, used an Intel 80286 processor, originally running at 6 MHz. It had a 16-bit ISA bus and 20 MB hard drive. A faster model, running at 8 MHz and sporting a 30-megabyte hard disk[143] was introduced in 1986.[144]

The AT was designed to support multitasking; the new SysRq (system request) key, little noted and often overlooked, is part of this design, as is the 80286 itself, the first Intel 16-bit processor with multitasking features (i.e. the 80286 protected mode). IBM made some attempt at marketing the AT as a multi-user machine, but it sold mainly as a faster PC for power users. For the most part, IBM PC/ATs were used as more powerful DOS (single-tasking) personal computers, in the literal sense of the PC name.

Early PC/ATs were plagued with reliability problems, in part because of some software and hardware incompatibilities, but mostly related to the internal 20 MB hard disk, and High Density Floppy Disk Drive.[145]

While some people blamed IBM's hard disk controller card and others blamed the hard disk manufacturer Computer Memories Inc. (CMI), the IBM controller card worked fine with other drives, including CMI's 33-MB model. The problems introduced doubt about the computer and, for a while, even about the 286 architecture in general, but after IBM replaced the 20 MB CMI drives, the PC/AT proved reliable and became a lasting industry standard.

IBM AT's Drive parameter table listed the CMI-33 as having 615 cylinders instead of the 640 the drive was designed with, as to make the size an even 30 MB. Those who re-used the drives mostly found that the 616th cylinder was bad due to it being used as a landing area.

AT/370

The "IBM Personal Computer AT/370" was an AT with two custom 16-bit cards, running almost exactly the same setup as the XT/370.

Convertible

The IBM PC Convertible, released April 3, 1986, was IBM's first laptop computer and was also the first IBM computer to utilize the 3.5" floppy disk which went on to become the standard. Like modern laptops, it featured power management and the ability to run from batteries. It was the follow-up to the IBM Portable and was model number 5140. The concept and the design of the body was made by the German industrial designer Richard Sapper.

It utilized an Intel 80c88 CPU (a CMOS version of the Intel 8088) running at 4.77 MHz, 256 kB of RAM (expandable to 640 kB), dual 720 kB 3.5" floppy drives, and a monochrome CGA-compatible LCD screen at a price of $2,000. It weighed 13 pounds (5.9 kg) and featured a built-in carrying handle.

The PC Convertible had expansion capabilities through a proprietary ISA bus-based port on the rear of the machine. Extension modules, including a small printer and a video output module, could be snapped into place. The machine could also take an internal modem, but there was no room for an internal hard disk. Discontinued in August of 1989, the IBM PC Convertible was the only IBM PC model to last beyond the April 2, 1987 discontinuation of all other models.

Next-generation IBM PS/2

The IBM PS/2 line was introduced in 1987. The Model 30 at the bottom end of the lineup was very similar to earlier models; it used an 8086 processor and an ISA bus. The Model 30 was not "IBM compatible" in that it did not have standard 5.25-inch drive bays; it came with a 3.5-inch floppy drive and optionally a 3.5-inch-sized hard disk. Most models in the PS/2 line further departed from "IBM compatible" by replacing the ISA bus completely with Micro Channel Architecture. The MCA bus was not received well by the customer base for PC's, since it was proprietary to IBM. It was rarely implemented by any of the other PC-compatible makers. Eventually IBM would abandon this architecture entirely and return to the standard ISA bus.

Technology

Electronics

.jpg)

The main circuit board in a PC is called the motherboard (IBM terminology calls it a planar). This mainly carries the CPU and RAM, and has a bus with slots for expansion cards. Also on the motherboard are the ROM subsystem, DMA and IRQ controllers, coprocessor socket, sound (PC speaker, tone generation) circuitry, and keyboard interface. The original PC also has a cassette interface.

The bus used in the original PC became very popular, and it was later named ISA. It was originally known as the PC-bus or XT-bus; the term ISA arose later when industry leaders chose to continue manufacturing machines based on the IBM PC AT architecture rather than license the PS/2 architecture and its Micro Channel bus from IBM. The XT-bus was then retroactively named 8-bit ISA or XT ISA, while the unqualified term ISA usually refers to the 16-bit AT-bus (as better defined in the ISA specifications). The AT-bus is an extension of the PC-/XT-bus and is in use to this day in computers for industrial use, where its relatively low speed, 5-volt signals, and relatively simple, straightforward design (all by year 2011 standards) give it technical advantages (e.g. noise immunity for reliability).

A monitor and any floppy or hard disk drives are connected to the motherboard through cables connected to graphics adapter and disk controller cards, respectively, installed in expansion slots. Each expansion slot on the motherboard has a corresponding opening in the back of the computer case through which the card can expose connectors; a blank metal cover plate covers this case opening (to prevent dust and debris intrusion and control airflow) when no expansion card is installed. Memory expansion beyond the amount installable on the motherboard was also done with boards installed in expansion slots, and I/O devices such as parallel, serial, or network ports were likewise installed as individual expansion boards. For this reason, it was easy to fill the five expansion slots of the PC, or even the eight slots of the XT, even without installing any special hardware. Companies like Quadram and AST addressed this with their popular multi-I/O cards which combine several peripherals on one adapter card that uses only one slot; Quadram offered the QuadBoard and AST the SixPak.

Intel 8086 and 8088-based PCs require expanded memory (EMS) boards to work with more than 640 kB of memory. (Though the 8088 can address one megabyte of memory, the last 384 kB of that is used or reserved for the BIOS ROM, BASIC ROM, extension ROMs installed on adapter cards, and memory address space used by devices including display adapter RAM and even the 64 kB EMS page frame itself.) The original IBM PC AT used an Intel 80286 processor which can access up to 16 MB of memory (though standard DOS applications cannot use more than one megabyte without using additional APIs). Intel 80286-based computers running under OS/2 can work with the maximum memory.

Peripheral integrated circuits

The set of peripheral chips selected for the original IBM PC defined the functionality of an IBM compatible. These became the de facto base for later application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) used in compatible products.

The original system chips were one Intel 8259 programmable interrupt controller (PIC) (at I/O address 0x20), one Intel 8237 direct memory access (DMA) controller (at I/O address 0x00), and an Intel 8253 programmable interval timer (PIT) (at I/O address 0x40). The PIT provides the 18.2 Hz clock ticks, dynamic memory refresh timing, and can be used for speaker output;[146] one DMA channel is used to perform the memory refresh.

The mathematics coprocessor was the Intel 8087 using I/O address 0xF0. This was an option for users who needed extensive floating-point arithmetic, such as users of computer-aided drafting.

The IBM PC AT added a second, slave 8259 PIC (at I/O address 0xA0), a second 8237 DMA controller for 16-bit DMA (at I/O address 0xC0), a DMA address register (implemented with a 74LS612 IC) (at I/O address 0x80),[147] and a Motorola MC146818 real-time clock (RTC) with nonvolatile memory (NVRAM) used for system configuration (replacing the DIP switches and jumpers used for this purpose in PC and PC/XT models (at I/O address 0x70).[148] On expansion cards, the Intel 8255 programmable peripheral interface (PPI) (at I/O addresses 0x378 is used for parallel I/O controls the printer,[149] and the 8250 universal asynchronous receiver/transmitter (UART) (at I/O address 0x3F8 or 0x3E8) controls the serial communication at the (pseudo-)[150] RS-232 port.

Joystick port

IBM offered a Game Control Adapter for the PC,[68] which supported analog joysticks similar to those on the Apple II. Although analog controls proved inferior for arcade-style games, they were an asset in certain other genres such as flight simulators. The joystick port on the IBM PC supported two controllers, but required a Y-splitter cable to connect both at once. It remained the standard joystick interface on IBM compatibles until being replaced by USB during the 2000s.

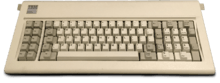

Keyboard

The keyboard that came with the IBM 5150 was an extremely reliable and high-quality electronic keyboard originally developed in North Carolina for the Datamaster.[52] Each key was rated to be reliable to over 100 million keystrokes. For the IBM PC, a separate keyboard housing was designed with a novel usability feature that allowed users to adjust the keyboard angle for personal comfort. Compared with the keyboards of other small computers at the time, the IBM PC keyboard was far superior and played a significant role in establishing a high-quality impression. For example, the industrial design of the adjustable keyboard, together with the system unit, was recognized with a major design award.[56] Byte magazine in the fall of 1981 went so far as to state that the keyboard was 50% of the reason to buy an IBM PC. The importance of the keyboard was definitely established when the 1983 IBM PCjr flopped, in very large part for having a much different and mediocre Chiclet keyboard that made a poor impression on customers. Oddly enough, the same thing almost happened to the original IBM PC when in early 1981 management seriously considered substituting a cheaper and lower quality keyboard. This mistake was narrowly avoided on the advice of one of the original development engineers.

However, the original 1981 IBM PC 83-key keyboard was criticized by typists for its non-standard placement of the Return and left ⇧ Shift keys, and because it did not have separate cursor and numeric pads that were popular on the pre-PC DEC VT100 series video terminals. In 1982, Key Tronic introduced a 101-key PC keyboard, albeit not with the now-familiar layout. In 1984, IBM corrected the Return and left ⇧ Shift keys on its AT keyboard, but shortened the Backspace key, making it harder to reach. In 1986, IBM introduced the 101 key Enhanced Keyboard, which added the separate cursor and numeric key pads, relocated all the function keys and the Ctrl keys, and the Esc key was also relocated to the opposite side of the keyboard. The Enhanced Keyboard was an option for the PC XT/AT in 1986, both of which were also available with their original keyboards, and introduced the key layout that's still the industry standard.

Another feature of the original keyboard is the relatively loud "click" sound each key made when pressed. Since typewriter users were accustomed to keeping their eyes on the hardcopy they were typing from and had come to rely on the mechanical sound that was made as each character was typed onto the paper to ensure that they had pressed the key hard enough (and only once), the PC keyboard used a keyswitch that produced a click and tactile bump intended to provide that same reassurance.

The IBM PC keyboard is very robust and flexible. The low-level interface for each key is the same: each key sends a signal when it is pressed and another signal when it is released. An integrated microcontroller in the keyboard scans the keyboard and encodes a "scan code" and "release code" for each key as it is pressed and released separately. Any key can be used as a shift key, and a large number of keys can be held down simultaneously and separately sensed. The controller in the keyboard handles typematic operation, issuing periodic repeat scan codes for a depressed key and then a single release code when the key is finally released.

An "IBM PC compatible" may have a keyboard that does not recognize every key combination a true IBM PC does, such as shifted cursor keys. In addition, the "compatible" vendors sometimes used proprietary keyboard interfaces, preventing the keyboard from being replaced.

Although the PC/XT and AT used the same style of keyboard connector, the low-level protocol for reading the keyboard was different between these two series. The AT keyboard uses a bidirectional interface which allows the computer to send commands to the keyboard. An AT keyboard could not be used in an XT, nor the reverse. Third-party keyboard manufacturers provided a switch on some of their keyboards to select either the AT-style or XT-style protocol for the keyboard.

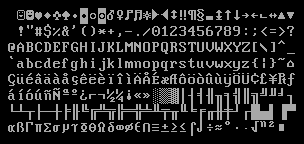

Character set

The original IBM PC used the 7-bit ASCII alphabet as its basis, but extended it to 8 bits with nonstandard character codes. This character set was not suitable for some international applications, and soon a veritable cottage industry emerged providing variants of the original character set in various national variants. In IBM tradition, these variants were called code pages. These codings are now largely obsolete, having been replaced by more systematic and standardized forms of character coding, such as ISO 8859-1, Windows-1251 and Unicode. The original character set is known as code page 437.

Storage media

Cassette tape

IBM equipped the model 5150 with a cassette port for connecting a cassette drive and assumed that home users would purchase the low-end model and save files to cassette tapes as was typical of home computers of the time. However, adoption of the floppy- and monitor-less configuration was low; few (if any) IBM PCs left the factory without a floppy disk drive installed. Also, DOS was not available on cassette tape, only on floppy disks (hence "Disk Operating System"). 5150s with just external cassette recorders for storage could only use the built-in ROM BASIC as their operating system. As DOS saw increasing adoption, the incompatibility of DOS programs with PCs that used only cassettes for storage made this configuration even less attractive. The ROM BIOS supported cassette operations.

The IBM PC cassette interface encodes data using frequency modulation with a variable data rate. Either a one or a zero is represented by a single cycle of a square wave, but the square wave frequencies differ by a factor of two, with ones having the lower frequency. Therefore, the bit periods for zeros and ones also differ by a factor of two, with the unusual effect that a data stream with more zeros than ones will use less tape (and time) than an equal-length (in bits) data stream containing more ones than zeros, or equal numbers of each.

IBM also had an exclusive license agreement with Microsoft to include BASIC in the ROM of the PC; clone manufacturers could not have ROM BASIC on their machines, but it also became a problem as the XT, AT, and PS/2 eliminated the cassette port and IBM was still required to install the (now useless) BASIC with them. The agreement finally expired in 1991 when Microsoft replaced BASICA/GW-BASIC with QBASIC. The main core BASIC resided in ROM and "linked" up with the RAM-resident BASIC.COM/BASICA.COM included with PC DOS (they provided disk support and other extended features not present in ROM BASIC). Because BASIC was over 50 kB in size, this served a useful function during the first three years of the PC when machines only had 64–128 kB of memory, but became less important by 1985. For comparison, clone makers such as Compaq were forced to include a version of BASIC that resided entirely in RAM.

Floppy diskettes

The first IBM 5150 PCs had two 5.25-inch 160 KiB single sided double density (SSDD) floppy disk drives. As two heads drives became available in the spring of 1982, later IBM PC and compatible computers could read 320 KiB double sided double density (DSDD) disks with software support of MS-DOS 1.25 and higher. The same type of physical diskette media could be used for both drives but a disk formatted for double-sided use could not be read on a single-sided drive. PC DOS 2.0 added support for 180 KiB and 360 KiB SSDD and DSDD floppy disks, using the same physical media again.

The disks were Modified Frequency Modulation (MFM) coded in 512-byte sectors, and were soft-sectored.[151] They contained 40 tracks per side at the 48 track per inch (TPI) density,[152] and initially were formatted to contain eight sectors per track. This meant that SSDD disks initially had a formatted capacity of 160 kB,[153] while DSDD disks had a capacity of 320 kB.[154] However, the PC DOS 2.0 and later operating systems allowed formatting the disks with nine sectors per track. This yielded a formatted capacity of 180 kB with SSDD disks/drives,[155] and 360 kB with DSDD disks/drives.[156] The unformatted capacity of the floppy disks was advertised as "250KB" for SSDD and "500KB" for DSDD ("KB" ambiguously referring to either 1000 or 1024 bytes; essentially the same for rounded-off values), however these "raw" 250/500 kB were not the same thing as the usable formatted capacity; under DOS, the maximum capacity for SSDD and DSDD disks was 180 kB and 360 kB, respectively. Regardless of type, the file system of all floppy disks (under DOS) was FAT12.

After the upgraded 64k-256k motherboard PCs arrived in early 1983, single-sided drives and the cassette model were discontinued.

IBM's original floppy disk controller card also included an external 37-pin D-shell connector. This allowed users to connect additional external floppy drives by third party vendors, but IBM did not offer their own external floppies until 1986.

The industry-standard way of setting floppy drive numbers was via setting jumper switches on the drive unit, however IBM chose to instead use a method known as the "cable twist" which had a floppy data cable with a bend in the middle of it that served as a switch for the drive motor control. This eliminated the need for users to adjust jumpers while installing a floppy drive.

Fixed disks

The 5150 could not itself power hard drives without retrofitting a stronger power supply, but IBM later offered the 5161 Expansion Unit, which not only provided more expansion slots, but also included a 10 MB (later 20 MB) hard drive powered by the 5161's own separate 130-watt power supply. The IBM 5161 Expansion Unit was released in early 1983.

During the first year of the IBM PC, it was commonplace for users to install third-party Winchester hard disks which generally connected to the floppy controller and required a patched version of PC DOS which treated them as a giant floppy disk (there was no subdirectory support).

IBM began offering hard disks with the XT, however the original PC was never sold with them. Nonetheless, many users installed hard disks and upgraded power supplies in them.

After floppy disks became obsolete in the early 2000s, the letters A and B became unused. But for 25 years, virtually all DOS-based PC software assumed the program installation drive was C, so the primary HDD continues to be "the C drive" even today. Other operating system families (e.g. Unix) are not bound to these designations.

OS support

Which operating system IBM customers would choose was at first unclear.[91][27] Although the company expected that most would use PC DOS[54] IBM supported using CP/M-86—which became available six months after DOS[157]—or UCSD p-System as operating systems.[68] IBM promised that it would not favor one operating system over the others; the CP/M-86 support surprised Gates, who claimed that IBM was "blackmailed into it".[91] IBM was correct, nonetheless, in its expectation; one survey found that 96.3% of PCs were ordered with the $40 DOS compared to 3.4% for the $240 CP/M-86.[158]

The IBM PC's ROM BASIC and BIOS supported cassette tape storage. PC DOS itself did not support cassette tape storage. PC DOS version 1.00 supported only 160 kB SSDD floppies, but version 1.1, which was released nine months after the PC's introduction, supported 160 kB SSDD and 320 kB DSDD floppies. Support for the slightly larger nine sector per track 180 kB and 360 kB formats arrived 10 months later in March 1983.

BIOS

The BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) provided the core ROM code for the PC. It contained a library of functions that software could call for basic tasks such as video output, keyboard input, and disk access in addition to interrupt handling, loading the operating system on boot-up, and testing memory and other system components.

The original IBM PC BIOS was 8k in size and occupied four 2k ROM chips on the motherboard, with a fifth and sixth empty slot left for any extra ROMs the user wished to install. IBM offered three different BIOS revisions during the PC's lifespan. The initial BIOS was dated April 1981 and came on the earliest models with single-sided floppy drives and PC DOS 1.00. The second version was dated October 1981 and arrived on the "Revision B" models sold with double-sided drives and PC DOS 1.10. It corrected some bugs, but was otherwise unchanged. Finally, the third BIOS version was dated October 1982 and found on all IBM PCs with the newer 64k-256k motherboard. This revision was more-or-less identical to the XT's BIOS. It added support for detecting ROMs on expansion cards as well as the ability to use 640k of memory (the earlier BIOS revisions had a limit of 544k). Unlike the XT, the original PC remained functionally unchanged from 1983 until its discontinuation in early 1987 and did not get support for 101-key keyboards or 3.5" floppy drives, nor was it ever offered with half-height floppies.

Video output

IBM initially offered two video adapters for the PC, the Color/Graphics Adapter and the Monochrome Display and Printer Adapter. CGA was intended to be a typical home computer display; it had NTSC output and could be connected to a composite monitor or a TV set with an RF modulator in addition to RGB for digital RGBI-type monitors, although IBM did not offer their own RGB monitor until 1983. Supported graphics modes were 40 or 80×25 color text with 8×8 character resolution, 320×200 bitmap graphics with two fixed 4-color palettes, or 640×200 monochrome graphics.

The MDA card and its companion 5151 monitor supported only 80×25 text with a 9×14 character resolution (total pixel resolution was 720×350). It was mainly intended for the business market and so also included a printer port.

During 1982, the first third-party video card for the PC appeared when Hercules Computer Technologies released a clone of the MDA that could use bitmap graphics. Although not supported by the BIOS, the Hercules Graphics Adapter became extremely popular for business use due to allowing sharp, high resolution graphics plus text and itself was widely cloned by other manufacturers.