Huey Long

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893 – September 10, 1935), nicknamed "The Kingfish," was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a member of the United States Senate from 1932 until his assassination in 1935. A populist member of the Democratic Party, he rose to national prominence during the Great Depression, attacking President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal from the left. As the political leader of Louisiana, he commanded wide networks of supporters and was willing to take forceful action. Celebrated as a populist benefactor or conversely denounced as a fascistic demagogue, Long remains a controversial figure.

Huey Long | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Louisiana | |

| In office January 25, 1932 – September 10, 1935 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph E. Ransdell |

| Succeeded by | Rose Long |

| 40th Governor of Louisiana | |

| In office May 21, 1928 – January 25, 1932 | |

| Lieutenant | Paul Narcisse Cyr Alvin Olin King |

| Preceded by | Oramel H. Simpson |

| Succeeded by | Alvin Olin King |

| Chair of the Louisiana Public Service Commission | |

| In office 1922–1926 | |

| Preceded by | Shelby Taylor |

| Succeeded by | Francis Williams |

| Louisiana Public Service Commissioner | |

| In office 1918–1928 | |

| Preceded by | Burk A. Bridges |

| Succeeded by | Harvey Fields |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Huey Pierce Long Jr. August 30, 1893 Winnfield, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | September 10, 1935 (aged 42) Baton Rouge, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Assassination (gunshot wound) |

| Resting place | Louisiana State Capitol |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Relations | Long family |

| Children | 3, including Russell B. Long |

| Alma mater | Oklahoma Baptist University University of Oklahoma College of Law Tulane University Law School |

| Signature | |

| Website | Official website |

| Nickname(s) | "The Kingfish" |

Long was born in the poor north of Louisiana in 1893. After working as a traveling salesman and attending multiple colleges, Long earned his law degree from Tulane University Law School. After a private legal career, in which he protected workers against corporations, Long was elected to the Louisiana Public Service Commission. As Commissioner, Long often prosecuted large corporations, such as Standard Oil. After successfully arguing before the US Supreme Court, Chief Justice William Howard Taft praised Long as "the most brilliant lawyer who ever practiced before the United States Supreme Court."

After a failed 1924 campaign, Long was elected Governor of Louisiana in 1928. After angering the establishment, he was impeached in 1929, but acquitted by the Louisiana Senate. During Long's years in power, he gained major state expansion in investments in infrastructure, education, and health care. Long was notable among southern politicians for avoiding race baiting and white supremacy. Under Long's leadership, hospitals and educational institutions were expanded, a system of charity hospitals was set up that provided health care for the poor, and massive highway construction and free bridges brought an end to rural isolation.

Long successfully ran for the US Senate in 1930, although he did not assume his seat until 1932. Long helped President Franklin D. Roosevelt secure his nomination and was a supporter through his first 100 days in office. However, Long split with Roosevelt in June 1933, becoming a prominent critic of his New deal. As an alternative, he proposed his "Share Our Wealth" program in 1934. To stimulate the economy, Long advocated massive federal spending, a wealth tax, and wealth redistribution. Poised to perform well in a presidential bid for 1936, Long was assassinated in 1935 at the age of 42. Although originally blamed on a lone assassin, many now believe Long was accidentally shot by his own bodyguards.

Although Long's movement soon faded, Roosevelt adopted many of his proposals in the Second New Deal. In Louisiana, Long permanently altered the political landscape. Elections would be organized along anti- or pro-Long factions into the 1960s. He also left behind a political dynasty, which included his wife, Senator Rose McConnell Long; his son, Senator Russell B. Long; and his brothers, Governor Earl Kemp Long, and US Representative George S. Long, among others.

Early life (1893–1915)

Childhood

Long was born on August 30, 1893, near Winnfield, a small town in the north-central part of Louisiana and the seat of Winn Parish.[1] He was the son of Huey Pierce Long Sr. (1852–1937) and the former Caledonia Palestine Tison (1860–1913), and the seventh of the couple's nine surviving children.[2] He would later claim his heritage was a mixture of Dutch, English, French, Scottish, and Welsh.[3] When he was young, Winn Parish was a deeply impoverished region whose people, mostly modest Southern Baptists, were known for their cantankerous stubbornness and for being outsiders in Louisiana's political system.[1][4] During the Civil War, Winn Parish had been a stronghold of Unionism in an otherwise solidly Confederate state. At Louisiana's 1861 convention on secession, the delegate from the parish voted to remain in the union: “Who wants to fight to keep the Negroes for the wealthy planters?”[5] In the 1890s it was a bastion of the Populist Party, and in 1912 a plurality in Winn Parish (35%) had voted for the Socialist Party's presidential candidate, Eugene Debs.[2][4][6]

The degree of poverty in Winn Parish was extreme, but in general Louisiana was a very poor state. According to the 1930 census, one-fifth of White Louisianans were illiterate, with rates for Black Louisianans being much higher because of underfunding of their education by racial discrimination. Having grown up in Winn Parish, Long absorbed all of the resentments of its people against the elite in Baton Rouge who ruled Louisiana.[7] While Long often told his followers that he came from the lowest possible social and economic stratum, Long's family were well-off compared to others in the largely destitute community of Winnfield.[1][8]

For people of their time and socioeconomic standing, Long's parents were well-educated, and stressed often to their child the importance of learning.[2] For many years, Long was home-schooled; he started attending local schools at about age 11. During his time in the public system, he earned a reputation as an excellent student with a remarkable memory. After growing bored with the required schoolwork, he eventually convinced his teachers to let him skip seventh grade.[9] When he was a student at Winnfield High School, he and his friends formed a secret society, advertising their exclusivity by wearing a red ribbon. According to Long, his club's mission was "to run things, laying down certain rules the students would have to follow."[10]

The teachers at the school eventually learned of Long's antics and warned him to obey the school and its faculty's rules. Long continued to rebel, eventually writing and distributing a flyer that criticized both his teachers and the necessity of a recently state mandated twelfth grade. He was expelled in 1910. Long drafted a petition calling for the principal of Winnfield High School to be removed from his post. He convinced enough people in his town to sign it, to gain the firing of the principal. Despite this success, Long never returned to high school, although he was awarded a diploma posthumously.[9][10]

In high school, Long proved himself to be a capable debater. At a statewide debating competition in Baton Rouge, he won a debating scholarship to Louisiana State University (LSU).[9][11] Because the award did not include money for textbooks or living expenses, he was unable to attend, as his family did not have the money to spare. Long would later regret that he had been unable to pursue an education at LSU.[11] Instead of trying to gain higher education, he spent most of the early 1910s as a traveling salesman, selling books, canned goods and patent medicine, as well as working as an auctioneer.[9]

Education and marriage

In September 1911, Long attended seminary classes at Oklahoma Baptist University in Shawnee, Oklahoma at the urging of his mother, a devout Baptist. While living with his brother George there, Long attended for only one semester, and rarely appeared at lectures. After deciding he was not suited to preaching, Long instead began to focus on law.[9][12] Borrowing one hundred dollars from his brother (which he later lost playing roulette in Oklahoma City), he attended the University of Oklahoma College of Law in Norman, Oklahoma for a semester in 1912.[12] To earn money while studying law part-time, he worked as a salesman for the Dawson Produce Company. Of the four classes Long took, he received one incomplete and three C's. He later confessed that he "didn't learn much law there" because there was "too much excitement, all those gambling houses and everything."[12] Long was arrested in 1912, supposedly for creating a disturbance in a brothel.[13] In his version of events, the police mistakenly arrested him after one man shot at another, but Long was able to prove he had been attending a play with Rose McConnell at the time of the incident and he was released.[14]

In 1913, Long married Rose McConnell. She was a stenographer who had won a baking contest which he promoted to sell "Cottolene," one of the most popular of the early vegetable shortenings to come on the market.[15] The two began a two-and-a-half year courtship and married on April 12, 1913 at the Gayoso Hotel in Memphis, Tennessee.[16] On their wedding day, Long had no cash with him, and had to borrow $10 from his fiancée to pay for the officiant.[17] The Longs had a daughter, also named Rose, and two sons: Russell B. Long, who subsequently became a long-term U.S. senator, and Palmer Reid Long (1921–2010), who became an oilman in Shreveport.[18][19] Long wrote in his 1933 autobiography, Every Man a King "If the loyalty of a wife and children could have elevated anyone in public life, I had that for complete success."[20]

Long enrolled at Tulane University Law School in New Orleans in the fall of 1914.[21] After a year of study that concentrated on the courses necessary for the bar exam, he successfully petitioned the Louisiana Supreme Court for permission to take the test before its scheduled June 1915 date. He was examined in May, passed, and received his license to practice.[22] He was later awarded an honorary Doctor of Law degree from Loyola University New Orleans.[23]

Legal career (1915–1923)

In 1915, Long began a private practice in Winnfield. Later, in Shreveport, he spent ten years representing small plaintiffs against large businesses. These were typically workers' compensation cases.[24][25] He often said proudly that he never took a case against a poor man. He was noted for successfully defending a widow against the Winnfield Bank, even though its president was Long's uncle.[24]

In 1918, Long invested $1,050 in an oil well that eventually struck oil. But the well was unable to make any money because the powerful Standard Oil Company refused to accept any of its oil, costing Long his investment.[26] This episode served as the catalyst for Long's lifelong hatred of the Standard Oil Company, which he later called an "Invisible Empire" run by "petroleumites."[27] In 1921, Long waged his first legal battle with Standard Oil when he represented a small oil firm that was suing the giant over a lease dispute.[28]

In 1918, Long entered into the race to serve on the three-seat Louisiana Railroad Commission. According to William Ivy Hair, Long's political message which he used to campaign for a seat on the commission:

... would be repeated until the end of his days: he was a young warrior of and for the plain people, battling the evil giants of Wall Street and their corporations; too much of America's wealth was concentrated in too few hands, and this unfairness was perpetuated by an educational system so stacked against the poor that (according to his statistics) only fourteen out of every thousand children obtained a college education. The way to begin rectifying these wrongs was to turn out of office the corrupt local flunkies of big business ... and elect instead true men of the people, such as [himself].[29]

In the Democratic primary, Long came in second behind incumbent Burk Bridges. Since no candidate managed to garner a majority of the votes, a run-off election was held, for which Long campaigned tirelessly across the whole north of the state. When the final counts were in, Long managed to defeat Burk by 636 votes.[30] Long performed extremely poorly in the urban areas of Alexandria, Shreveport, and Monroe but won over the country crowd in large numbers. Soon thereafter, State Senator Delos Johnson of Franklinton sent the young Long a letter of congratulations that "recognized [him] as a comer."[25]

The Louisiana Railroad Commission and its members were known for largely having yielded to the goals of the state's powerful stakeholders. But, once sworn in to office, Long refused to play by such rules. According to biographer Richard D. White Jr., Long "crusaded for lower utility rates, forced the railroads to extend their service to small villages and hamlets, and demanded that the Standard Oil Company end the importation of Mexican crude oil and use more oil from Louisiana wells."[31]

In the gubernatorial election of 1920, Long campaigned prominently for John M. Parker; today Long is often credited with helping Parker to win in the northern Louisiana parishes.[32][33] But after Parker was elected to the gubernatorial office, the two became bitter rivals. This break was largely the result of Long having demanded that Parker declare the state's oil pipelines to be public utilities, and Parker having refused to do so.[32]

In particular, Long was horrified and became furious when Parker allowed the oil companies, led by the legal team of Standard Oil, to assist in writing the state's severance tax laws—laws that decreed how much money corporations such as Standard Oil had to pay the state for the extraction of natural resources. Because the governor was willing to go along with companies like Standard Oil, Huey began calling Parker the "chattel" of the corporations.[34] After butting heads, Parker tried in 1921 to have Huey ousted from his position on the Louisiana Railroad Commission, although he was unable to do so.[32]

By 1922, the Railroad Commission had been renamed "the Public Service Commission", on which Long retained a seat. He soon dedicated his life to adding "new energy and independence into the agency", as well as increasing the commission's (and, by extension, his own) power.[31] In 1922, Long won a lawsuit against the Cumberland Telephone & Telegraph Company for unfair rate increases; he successfully argued the case on appeal before the United States Supreme Court, resulting in cash refunds totaling $440,000 being sent to 80,000 overcharged customers. After the case, Chief Justice William Howard Taft described Long as "the most brilliant lawyer who ever practiced before the United States Supreme Court."[35][34][36]

Gubernatorial campaigns (1924–1928)

1924 election

Long ran for governor of Louisiana in the election of 1924, attacking outgoing Governor Parker, Standard Oil, and the established political hierarchy both locally and statewide. In that campaign, he became one of the first Southern politicians to use radio addresses and sound trucks. Long also began wearing a distinctive white linen suit.

Long came in third, missing the runoff by 7,400 votes.[28] Long still performed well, especially for a man of his age. He polled almost 72,000 votes, around 31% of the electorate. He performed best in the poorer rural north.[37]

Although he and another candidate had opposed the powerful Ku Klux Klan, a third candidate had openly supported the group. The Klan's prominence in Louisiana was the primary issue of the campaign. Long attempted to remain neutral on the topic, alienating both sides. Long also failed to attract Catholic voters, limiting his chances in the South. This was clearly seen in the Catholic majority New Orleans, where he polled 12,000 votes, just 17%.[37]

Long also cited rain on election day as suppressing voter turnout among his base in rural north Louisiana, where voters were unable to reach the polls over the dirt roads that had turned to mud.[38][37]

Long was reelected later in the year to the Public Service Commission. After he resigned in 1927 to campaign for governor, his former law partner and political ally, Harvey Fields, a former state senator for Union and Morehouse parishes, succeeded Long on the PSC, serving from 1927 to 1936.

1928 election

— An example of Long's 1928 campaign rhetoric[28]

Long spent the intervening four years building his reputation and his political organization, including supporting Roman Catholic candidates to build support in southern Louisiana, which was heavily Catholic due to its French and Spanish heritage. In 1928 he again ran for governor, campaigning with the slogan, "Every man a king, but no one wears a crown," a phrase adopted from Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan.[39] Long's attacks on the utilities industry and corporate privileges were enormously popular, as was his depiction of the wealthy as parasites who grabbed more than their fair share of the public wealth while marginalizing the poor.

Long criss-crossed the state, campaigning in rural areas disenfranchised by the New Orleans-based political establishment, known as the "Old Regulars" or "the Ring." They controlled much of the state through alliances with sheriffs and other local officials. At the time, the rural poor comprised 60 percent of the state's population. The entire state had roughly three hundred miles of paved roads and only three major bridges, none of which crossed the Mississippi. The literacy rate was the lowest in the nation (75 percent illiterate), as most families could not afford to purchase the textbooks required for their children to attend school. A poll tax kept many poor whites from voting; of the two million residents, only 300,000 could afford to register to vote.[40] In addition, with selective application of literacy tests, blacks had been effectively and completely disenfranchised since soon after the state legislature passed the new constitution in 1898.[41]

Long developed novel campaign techniques, including the use of sound trucks at mass meetings and radio commercials.[37] When campaigning, Long would often hold a Bible in one hand and quote liberally from the scriptures.[42] When asked about his main influence, he always cited the Bible first and foremost. Once he said that he did not "know how many times [he had] read it through."[43] However, Long's brother Julius later said that the only biblical material Huey mastered was that which his mother had read to him.[43] Long also began using a new slogan: "Every Man a King, But No One Wears a Crown."[44]

One of the campaign issues, Long's proposal to let contracts for "free bridges" over Lake Pontchartrain, was ultimately endorsed by his two 1928 opponents, sitting Governor Oramel H. Simpson and U.S. Representative Riley J. Wilson of Louisiana's 5th congressional district. Free ferries ran while construction proceeded on the bridges. The previous toll bridge charge of $8.40 was reduced to 60 cents.[45]

Long won the 1928 gubernatorial election in large part by tapping into the class resentment of rural residents. He proposed government services far more expansive than anything in his state's history. His campaign manager was the Catholic Cajun Harvey Peltier, Sr., a state representative and lawyer/banker from Thibodaux in Lafourche Parish.[46] Long had the backing of the timber businessman Swords Lee, his cousin by marriage and a former state representative for Grant Parish.[47]

On January 17, 1928, Long won the Democratic primary election but failed to secure a majority of the vote. He polled 126,842 votes (43.9 percent). His opponents split the remaining 56 percent of the ballots. Representative Riley J. Wilson earned 81,747 votes (28.3 percent), and the short-term incumbent Governor Oramel Simpson garnered 80,326 (27.8 percent). At the time, Long's margin was the largest in state history, and neither opponent chose to face him in a runoff election as was permitted in Louisiana. He was elected governor in the general election on April 17, 1928, with 92,941 votes (96.1 percent), to 3,733 for the Republican candidate, Etienne J. Caire.[48] Caire's running mate, John E. Jackson, a New Orleans lawyer who later took over the state Republican chairmanship, ran unsuccessfully for lieutenant governor[49] against Paul N. Cyr, with whom Long later had an irreconcilable break. Elected at age 34, Long remains the youngest governor of Louisiana.[50]

Long consolidated the Democratic factions in New Orleans and after his election drew the support of Rudolph Hecht, the president of Hibernia Bank who advocated industrial and commercial expansion, and Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley, who declared

an obligation I owe to my people and the people of this state to join hands with Governor Long and bury our political tomahawk so that the city and state can forge ahead ... The governor worked hard to develop a program we could all unite on; he was the victor, and he showed himself more generous ... When the roads and bridges he is planning are completed, more of the city people will be going to the country, and more people will be coming to the city ... Let us therefore forget all bickerings and let the capitalists and the laboring interests ... join hands as we have joined hands.[51]

Three Louisiana State University (LSU) scholars contend that before his governorship "political power in Louisiana had been nearly a monopoly of the coalition of businessmen and planters, reinforced by the oil and other industrial interests. This situation was changed when Long won the hearts and votes of the farmers and other 'small people' and created a countervailing power combination."[52]

At least one statewide official bucked the Long trend. Percy Saint of St. Mary Parish was reelected to a second term as Attorney General independent of Long and several times ruled against Long during his gubernatorial term.[53]

Louisiana Governorship (1928–32)

First year

Once in office as governor on May 21, 1928, Long moved quickly to consolidate his power, firing hundreds of opponents in the state bureaucracy, at all ranks from cabinet-level heads of departments and board members to rank-and-file civil servants and state road workers. Like previous governors, he filled the vacancies with patronage appointments from his own network of political supporters. Every state employee who depended on Long for a job was expected to pay a portion of his or her salary at election time directly into Long's political war-chest, which raised $50,000 to $75,000 each election cycle. The funds were kept in a famous locked "deduct box" to be used at Long's discretion for political and personal purposes. During his first few weeks as Governor, Long was frequently visited by his personal doctor, who was a proponent of reincarnation. The doctor suggested that Long was the reincarnated ego of Napoleon Bonaparte. Gripped by the idea, Long read several biographies on the French Emperor.[54] The American historian David Kennedy wrote that Long's regime in Louisiana was "the closest thing to a dictatorship that America has ever known".[7]

Once his control over the state's political apparatus was strengthened, Long pushed a number of bills through the 1929 session of the Louisiana State Legislature to fulfill campaign promises. These included a free textbook program for schoolchildren, an idea advanced by John Sparks Patton, the Claiborne Parish school superintendent, and the Long confidant, Representative Harley Bozeman of Winnfield. Long also supported night courses for adult literacy (which taught 100,000 adults to read by the end of his term), and a supply of cheap natural gas for the city of New Orleans.

Long began an unprecedented public works program, building roads, bridges, hospitals, and educational institutions. Huey P. Long's legislative agenda brought textbooks, a highway, natural gas heating to New Orleans, and buildings still standing at LSU.[55] His bills met opposition from many legislators, wealthy citizens, and the media, but Long used aggressive tactics to ensure passage of the legislation he favored. He would show up unannounced on the floor of both the House and Senate or in House committees, corralling reluctant representatives and state senators and bullying opponents.[56][57] When an opposing legislator suggested that Long was not familiar with Louisiana's Constitution, the Governor declared "I'm the Constitution around here now."[58] These tactics were unprecedented, but they resulted in the passage of most of Long's legislative agenda. By delivering on his campaign promises, Long achieved hero status among the state's rural poor population.

Long's free school-books angered Catholics, who usually sent their children to private schools. Long assured them that the books were to be granted directly to all children, whether or not they attended public-school. However, this was criticized by conservative constitutionalists, who sued. The case ultimately went to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favor of Long.[59] Even after Long secured passage of his free textbook program, the school board of Caddo Parish, home of conservative Shreveport, sued to prevent the books from being distributed, saying it would not accept "charity" from the state. Long responded by withholding authorization for locating an Army Air Corps base nearby until the parish accepted the books.[9]

Irritated by what he saw as immoral gambling in New Orleans, Long sent the National Guard to raid these establishments with orders to "shoot without hesitation." Gambling equipment was burned, prostitutes were arrested, and over $25,000 were confiscated for government funds. Local newspapers ran photos of nude women being forcibly searched by National Guardsmen. City authorities had not requested military force and martial law was not declared. The state's Attorney General denounced Long's actions as illegal, but was rebuked by Long: "Nobody asked him for his opinion."[60]

Despite wide disapproval, Long had the Governor's Mansion, built in 1887, razed by convicts from the State Penitentiary. In its place, Long had a much larger Georgian mansion built. It bore a strong resemblance to the White House, as Long reportedly wanted to be familiar with the White House when he became president.[61][62]

Impeachment

In 1929, Long called a special session of both houses of the legislature to enact a new five-cent per barrel "occupational license tax" on production of refined oil, to help fund his social programs. The bill was met with fierce opposition from the state's oil interests. Opponents in the legislature, led by freshman lawmakers Cecil Morgan of Shreveport and Ralph Norman Bauer of Franklin in St. Mary Parish, moved to impeach Long on charges ranging from blasphemy to abuses of power, bribery, and the misuse of state funds.[63]

Concerned, Long attempted to shut down the session. Pro-Long Speaker John B. Fournet called for a vote to adjourn; after voting, the board showed 67 ayes and 13 nays. This sparked confusion as one pro-Long congressman rigged the electric voting-machine to turn a "yes" into a "no" and vice versa.[64][65] This sparked a brawl across the floor of the state legislature, later known as "Bloody Monday".[65] After the fight, the legislature voted to remain in session and proceed with the impeachment.[66][67] Long was the first Louisiana governor to be charged in the state's history under four different nations.[68]

Nineteen charges were listed against Long. The most serious was subornation of murder. Harry A. Bozeman, one of Long's bodyguards, claimed in an affidavit that an intoxicated Long had told him to kill Representative J. Y. Sanders Jr. and "leave him in the ditch where nobody will know how or when he got there." Long allegedly promised him "a full pardon and many gold dollars."[65]

In his autobiography, Long indicates that he and his friends "were outraged at the persistence with which the big oil companies [which he called the Oil Trust] resisted the payment of taxes and with the political opposition they continued to give us."[69]

Long took his case to the people using his characteristic speaking tours. His ally Oscar K. Allen urged him to:

... fight fire with fire in this thing ... Get those circulars going. You'll sit here and be ruined. Get up a mass meeting! Get it up quick! In that instance, as I have many time of my life, I took the advice of O. K. Allen ... Immediately we set forth to call a mass meeting in the hostile center of Baton Rouge, calling upon people from all parts of the state to attend our first gathering to formulate plans to resist the impeachment.[70]

The anti-Long faction held mass-meetings to attack Long, often accompanied by the Standard Oil company band.[71]

The New Orleans Times-Picayune was leading the fight editorially against Long's proposed tax on oil. Long discovered that the petroleum companies had increased their advertising dollars in the newspaper. And he found that the attorney Arthur Hammond, a brother-in-law of The Times-Picayune's principal lawyer, was drawing $400 per month on two separate state payrolls. Quickly Hammond was removed from both positions.[72]

Long argued that Standard Oil, the corporate interests, and the conservative political opposition were conspiring to stop him from providing roads, books, and other programs to develop the state and to assist the poor and downtrodden. He claimed that Standard Oil had used up to $25,000 to bribe the legislature, which he called "enough money to burn a wet mule".[28] The House referred many charges to the Senate. Conviction required a two-thirds majority of the Senate, but Long produced a "Round Robin" statement signed by fifteen senators pledging to vote "not guilty" regardless of the evidence. These senators claimed that the trial was illegal, and even if proved, the charges did not warrant impeachment. The impeachment process, now futile, was suspended. It has been alleged that both sides used bribes to buy votes, and that Long later rewarded the Round Robin signers with state jobs or other favors.[73][74]

Following the failed impeachment attempt in the Senate, Long became ruthless when dealing with his enemies. He fired their relatives from state jobs and supported candidates to defeat them in elections. After impeachment, Long appeared to have concluded that extra-legal means would be needed to defend the interests of the common people against the powerful money interests. "I used to try to get things done by saying 'please'," said Long. "Now ... I dynamite 'em out of my path."[75] Since the state's newspapers were financed by the opposition, in March 1930 Long founded his own paper, the Louisiana Progress, which he used to broadcast achievements and denounce his enemies.[76] To receive lucrative state contracts, companies were first expected to buy advertisements in Long's newspaper. Long attempted to pass laws placing a surtax on newspapers and forbidding the publishing of "slanderous material," but these efforts were defeated. After the impeachment attempt, Long received death threats. Fearing for his personal safety, he surrounded himself with armed bodyguards at all times.[77][28]

Change of course

In the 1930 legislative session, Long proposed another major road-building initiative as well as the construction of a new capitol building in Baton Rouge.[78] The State Legislature defeated the bond issue necessary to build the roads, and his other initiatives failed as well.

Long responded by suddenly announcing his intention to run for the U.S. Senate in the Democratic primary of September 9, 1930. He portrayed his campaign as a referendum on his programs: if he won he would take it as a sign that the public supported his programs over the opposition of the legislature, and if he lost he promised to resign. His opponent was incumbent Senator Joseph E. Ransdell. At 72 years old, Ransdell had been in the Senate since Long was four years old. Ransdell was anti-Long, aligned with the Constitutional League and the New Orleans Ring. Ransdell also had the support of all 18 of the state's daily newspapers. Although initially promising not to issue personal attacks, Long seized on the issue of Ransdell's age. He claimed that Ransdell was senile and too old to purchase life-insurance, donning him "Old Feather Duster."[79] Long purchased two new $30,000 sound trucks and had inmates paint campaign signs. He also distributed over two million circulars attacking his opponent.[80] The campaign became increasingly vicious, with The New York Times calling it "as amusing as it was depressing."[81] Ultimately, on September 9, 1930, Long defeated Ransdell by 149,640 (57.3 percent) to 111,451 (42.7 percent).[82]

Although his Senate term began on March 4, 1931, Long completed most of his four-year term as governor, which did not end until May 1932. He declared that leaving the seat vacant for so long would not hurt Louisiana; "with Ransdell as Senator, the seat was vacant anyway." By not leaving the governor's mansion until January 25, 1932, Long prevented Lieutenant Governor Paul N. Cyr, a former ally, from succeeding to the office. A dentist and geologist from Jeanerette in Iberia Parish, Cyr had subsequently broken with Long and had been threatening to roll back his reforms if he succeeded to the governorship. In his autobiography, Long recalled:

On another occasion the greatest publicity was given to a charge made by Lieutenant Governor Cyr that I had performed a swindle worse than that of Teapot Dome in the execution of an oil lease ... The oil lease in question had been made by Governor Parker, and no act had been taken by me, except to permit the holder to enter into a drilling contract. Our reply was practically buried by most of the newspapers.[83]

Renewed strength

Having won the overwhelming support of the Louisiana electorate, Long returned to pushing his legislative program with renewed strength. Bargaining from an advantageous position, Long entered an agreement with his longtime New Orleans rivals, the Regular Democratic Organization and their leader, New Orleans mayor T. Semmes Walmsley. They would support his legislation and candidates in future elections in return for his support of the building of a bridge over the Mississippi River, an airport for New Orleans, and infrastructure improvements in the city. Long continued his intimidating practice of presiding over the legislature. When congressman voiced their concerns, Long would shout "Shut up!" or "Sit down!". In one night, Long was able to pass 44 bills in just two hours, or one every 3 minutes. He later explained his tactics: "The end justifies the means."[84] State Representative Gilbert L. Dupré of Opelousas once complained about a leak in the House roof just over his own desk in the chamber. When he asked Governor Long to repair the leak Long said that he would do so only if Dupré would vote for the planned new state capitol building. When Dupré refused to commit his vote, Long told him, "Die, damn you, in the faith!"[85]

Support from the Old Regulars enabled Long to pass an increase in the gasoline tax to finance road construction projects, new school spending, a construction of a new Louisiana State Capitol, and a $75 million bond for road construction. Including the Airline Highway between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, Long's road network gave Louisiana some of the most modern roads in the country and formed the state's highway system.[86] Long's opponents charged that he had become virtual dictator of the state.[87]

Long retained New Orleans architect Leon C. Weiss to design the state capitol, built in a skyscraper style nearly identical to the one built in Nebraska the previous decade, a new governor's mansion, the Charity Hospital in New Orleans, and many Louisiana State University buildings, and other college buildings throughout the state.

As governor, Long was not popular among the "old families" of Baton Rouge society or indeed in most of the state. He instead held gatherings of his leaders and friends who listened to the popular radio show Amos 'n' Andy. One of Long's followers dubbed him "the Kingfish" after the master of the Mystic Knights of the Sea lodge to which the fictional Amos and Andy belonged. The character of the "Kingfish" was a stereotypical, smooth-talking African-American conman who was forever trying to trick Amos and Andy into various get-rich schemes. The nickname stuck with Long's encouragement.[88]

In meetings, they would address him as "Your Truculency." He had his bodyguards "let go" on reporters, assaulting photographers, smashing cameras, and evicting them from government buildings. He had often criticized the press, denouncing the "lying newspapers".[89] In March 1930, Long established his own newspaper: the Louisiana Progress. The paper was extremely popular, widely distributed by policeman, highway workers, and government truckers.[90][89]

Long cultivated a mass-appeal, publicly declaring himself to be a common-man. He espoused the merit of "potlikker," the leftover water that vegetables and meat were boiled in. He declared it the "poor folks' staple - the food of the gods." He would often conduct government business barefoot in his pajamas.[91] On one occasion, he sported stripe pajamas while he boarded a visiting German warship carrying a German commander. Long's attire and the outraged German response became national news.[92] Long was showered with pajamas by supporters, and some campaign posters would even feature pajamas in reference to the event. Long repeated this crude reception when, only wearing underwear, he received a United States general and his aides. The Baton Rouge State-Times reflected, "If General McCoy is loath to believe that he had a narrow escape, and that the governor does not receive visitors in the nude, he is just not acquainted with our governor."[93]

As governor, Long became an ardent supporter of the state's primary public university, Louisiana State University (LSU) in Baton Rouge. He greatly increased LSU's state funding and expanded its enrollment from study programs that enabled poor students to attend LSU and he established the LSU Medical School in New Orleans. He also intervened in the university's affairs, choosing its president.[94] To generate excitement for the university, he quadrupled the size of the LSU band and co-wrote some of the music that is still played during football games, including "Touchdown for LSU."[95] Once, he had the football team run a play he created.[95] He would often tread the sidelines during football games and give locker-room talks to the team.[28]

Long created a public works program for Louisiana that was unprecedented in the South, constructing numerous roads, bridges, hospitals, schools and state buildings that have endured into the 21st century. During his four years as governor, Long increased paved highways in Louisiana from 331 to 2,301 miles (533 to 3,703 km), plus an additional 2,816 miles (4,532 km) of gravel roads. By 1936, the infrastructure program begun by Long had completed some 9,700 miles (15,600 km) of new roads, doubling the size of the state's road system. He built 111 bridges and started construction on the first bridge over the Mississippi entirely in Louisiana, the Huey P. Long Bridge in Jefferson Parish, near New Orleans. He built a new Governor's Mansion and the new Louisiana State Capitol, at the time the tallest building in the South. All of these projects provided thousands of much-needed jobs during the Great Depression, including 22,000—or 10 percent—of the nation's highway workers.[96]

Long's free textbooks, school-building program, and school busing improved and expanded the public education system.[97] His night schools taught 100,000 adults to read. He expanded funding for LSU, tripled enrollment, lowered tuition, and established scholarships for low-income students. He sometimes befriended persons in need. In 1932 a young Pap Dean, later political cartoonist with the Shreveport Times, wrote to Long after hearing him speak in Dean's native Colfax. Dean said he had lost his college funds in a bank closing. Long helped Dean procure financial aid to attend LSU, from which he graduated in 1937.[98] Long's statewide public health programs dramatically reduced the death rate in Louisiana. He provided free immunizations to nearly 70 percent of the population. He also reformed the prison system by providing medical and dental care for inmates. His administration funded the piping of natural gas to New Orleans and other cities. It also built the seven-mile (11 km) Lake Pontchartrain seawall and New Orleans airport.[99]

Long slashed personal property taxes and reduced utility rates. His repeal of the poll tax in 1935 increased voter registration by 76 percent in one year.[100] Long's popular homestead exemption eliminated personal property taxes for the majority of citizens by exempting properties valued at less than $2,000. His "Debt Moratorium Act" prevented foreclosures by giving people extra time to pay creditors and reclaim property without being forced to pay back-taxes. His personal intervention and strict regulation of the Louisiana banking system prevented bank closures and kept the system solvent. While 4,800 banks collapsed nationwide, only seven failed in Louisiana.[101]

In October 1931, Lieutenant Governor Cyr, by then Long's avowed enemy, argued that the Senator-elect could no longer remain governor. Cyr declared himself the state's legitimate governor. In response, Long ordered state National Guard troops to surround the State Capitol and fended off Cyr's proposed "coup d'état." Long then went to the Louisiana Supreme Court to have Cyr ousted as lieutenant governor. He argued that the office of lieutenant-governor was vacant because Cyr had resigned when he attempted to assume the governorship. His suit was successful. Under the state constitution, Senate president and Long ally Alvin Olin King became lieutenant-governor[102] and then, briefly from January to May 1932, governor.[103] Long chose his childhood friend, Oscar K. Allen, to succeed King in the January 1932 election on a "Complete the Work" ticket. With the support of Long's voter base and the Old Regular machine, Allen won easily, permitting Long to resign as governor and take his seat in the U.S. Senate in January 1932.

U.S. Senate (1932–1935)

Senator Long

Long's three-year tenure in the Senate overlapped an important time in American history as Herbert Hoover and then Franklin Delano Roosevelt attempted to deal with the Great Depression.

In January 1932, Long arrived at the United States Senate in Washington, D.C., where he took his oath and his seat, which once belonged to John C. Calhoun.[28] He was absent for a majority of the days in the 1932 session. With the backdrop of the Depression, he made characteristically fiery speeches that denounced the concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. He also criticized the leaders of both parties for failing to address the crisis adequately, most notably attacking conservative Senate Democratic Leader Joseph Robinson of Arkansas for his apparent closeness with President Herbert Hoover and ties to big business. Robinson had been the vice-presidential candidate in 1928 on the Democratic ticket opposite Hoover.[104] Long launched personal attacks, such as mocking Robinson's appearance: "he doesn't look really as well with his hair dyed."[28]

Long earned a reputation, as Williams wrote later, as "a leading member of the progressive bloc in the Senate."[105] In the presidential election of 1932, Long became a vocal supporter of the candidacy of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. He believed Roosevelt to be the only candidate willing and able to carry out the drastic redistribution of wealth that Long believed was necessary to end the Great Depression. At the Democratic National Convention, Long was instrumental in keeping the delegations of several wavering states in the Roosevelt camp. Long expected to be featured prominently in Roosevelt's campaign, but he was disappointed with a speaking tour limited to four Midwestern states.[106]

Long found other venues for his populist message. He campaigned to elect Senator Hattie Caraway of Arkansas, a widow and the underdog candidate in a crowded field, to her first full term in the Senate by conducting a whirlwind, seven-day tour of that state. (Caraway had been appointed to the seat after her husband's death.) He raised his national prominence and Caraway won by a landslide, defeating a candidate supported by Senator Joseph Robinson of Arkansas. With Long's help, Caraway became the first woman elected to the U.S. Senate. Caraway told Long, however, that she would continue to use independent judgment and not allow him to dictate how she would vote on Senate bills. She also insisted that he stop attacking Robinson while he was in Arkansas.[107]

Roosevelt and the New Deal

In the critical 100 days of Roosevelt's presidency in spring 1933, Long was generally a strong supporter of the New Deal, but differed with the president on patronage. Roosevelt wanted control of the patronage, and Long wanted to control it for his state. The two men broke in late 1933.[108] Aware that Roosevelt had no intention to radically redistribute the country's wealth, Long became one of the few national politicians to oppose Roosevelt's New Deal policies from the left. He considered them inadequate in the face of the escalating economic crisis. Long still sometimes supported Roosevelt's programs in the Senate, saying that "Whenever this administration has gone to the left I have voted with it, and whenever it has gone to the right I have voted against it."[109]

Long opposed the National Recovery Act, calling it a sellout to big business. On the Senate floor, he attacked the bill as having "every fault of socialism" yet not "one of its virtues." He claimed, correctly, that that NRA wage and price codes would be created by, and in the favor of, industrialists.[110] In an attempt to prevent its passage, Long held a lone filibuster, speaking for 15 hours and 30 minutes, the second longest filibuster at the time.[111][112] He also criticized Social Security, calling it inadequate and expressing his concerns that states would administer it in a way discriminatory to blacks.[113] In 1933, he was a leader of a three-week Senate filibuster against the Glass banking bill for favoring the interests of national banks over state banks. He later supported the Glass–Steagall Act, after provisions were made to extend government deposit insurance to state banks as well as national banks.[114]

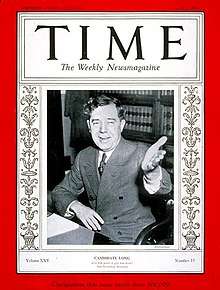

Long was known as one of the most colorful senators of all time, leading Kennedy to write that

"... Long strode into the national arena in the role of the hillbilly hero and played it with gusto. He wore white silk suits and pink silk ties, womanized openly, swilled whiskey in the finest bars, swaggered his way around Washington, and breathed defiance into the teeth of his critics. The president's mother called him 'that awful man'. His friends called him 'the Kingfish', after a character on the radio program Amos 'n' Andy ('Der Kingfish', said Long's critics, seeing parallels with another dangerous demagogue.) The New York Times called him 'a man with a front of brass and lungs of leather'."[115]

Fellow Senator Carter Glass said of Long, "I understand that in the ultimate decadence of Rome they elected a horse to the Senate. At least it was a whole horse."[116] Long's flamboyant ways and populist style made him one of the best known senators in the nation.[115]

His vulgar behavior was well publicized at a 1933 charity dinner in Long Island, to which he arrived already intoxicated. According to Time, "Spotting a plump girl with a full plate before her, he marched to her table, snatched the plate from her, yapped: 'You're too fat already. I'll eat this.'" Long's night culminated in him intentionally urinating on a man in the restroom. The man punched Long, giving him a black-eye. When asked about the injury, Long claimed that four men ambushed him.[117]

— Huey Long on Roosevelt's policies [118]

Roosevelt considered Long a radical demagogue. The president privately said of Long that, along with General Douglas MacArthur, "He was one of the two most dangerous men in America."[119] In June 1933, Long visited the White House to meet President Roosevelt, but the meeting was a disaster: Long was flagrantly disrespectful, refusing to take off his straw hat and addressing Roosevelt as "Frank", instead of the normal "Mr. President".[7]

Shortly thereafter, in June 1933, in an effort to undermine Long's political dominance, Roosevelt cut Long out of consultation on the distribution of federal funds or patronage in Louisiana and placed Long's opponents in charge of federal programs in the state. Roosevelt also supported a Senate inquiry into the election of Long ally John H. Overton to the Senate in 1932. The Long machine was charged with election fraud and voter intimidation, but the inquiry came up empty, and Overton was seated.[120] To discredit Long and damage his support base, Roosevelt had Long's finances investigated by the Internal Revenue Service in 1934.[121] Though they failed to link Long to any illegality, some of Long's lieutenants were charged with income tax evasion. Only one had been convicted by the time of Long's death.[122] Roosevelt's son would later note that in this instance, his father "may have been the originator of the concept of employing the IRS as a weapon of political retribution".[123]

Chaco War

Until 1934, Long was not known for his opinions on foreign policy. On 30 May 1934, Long took to the Senate floor to debate the abrogation of the Platt amendment.[124] Instead of debating the Platt amendment, Long gave his views on the Chaco War, coming out in support of Paraguay against Bolivia, as he maintained that US President Hayes had awarded the Chaco to Paraguay in 1878.[125] Long blamed the entire war on "the forces of imperialistic finance", claiming that Paraguay was the rightful owner of the Chaco. He said that Standard Oil, whom Long called "promoter of revolutions in Central America, South America and Mexico," had "bought" the Bolivian government and started the war because Paraguay was unwilling to grant them oil concessions.[125] Long ended his speech by claiming the entire bloody Chaco War was due to the machinations of Wall Street, called the American arms embargo to both sides as subservience to the "big papa" of Wall Street and stated: "Well should we begin on Memorial Day, the hour of mourning, to understand that the imperialistic principles of the Standard Oil Company have become mightier than the solemn treaties and pronouncements of the United States government".[126]

Long's speech made him a national hero in Paraguay while leading to protests from the Bolivian legation in Washington.[127] Long's thesis that the U.S. policy toward Latin America was dictated solely by the selfish concerns of oil companies, and that the U.S. was maintaining a pro-Bolivian neutrality only because that is what Standard Oil wanted, attracted much attention in Latin American newspapers. The State Department was greatly concerned about the damage Long was inflicting on the reputation of the U.S. Throughout the summer of 1934, American diplomats waged a sustained public relations campaign against Long throughout Latin America.[128]

In a second speech given on 7 June 1934, in response to the Bolivian protests, Long again supported Paraguay and attacked Standard Oil as "domestic murderers", "foreign murderers", "international conspirators," and "rapacious thieves and robbers".[129] Besides abusing Standard Oil, Long announced that since Bolivia was taking the Chaco dispute to the World Court, he was opposed to the United States joining the World Court, saying:

"Bolivia has run over to the famous World Court and the League of Nations. So here is the Standard Oil Company of the United States sailing under the title of Bolivia, putting one of their emissaries on a boat, and skyrocketing him to Geneva to renounce the Hayes award of the United States".[128]

In July 1934, after capturing a Bolivian fort, the Paraguayans renamed it Fort Long.[128]

In terms of foreign policy, Long established himself as a firm isolationist. He argued that the United States involvement in the Spanish–American War and the First World War had been deadly mistakes conducted on behalf of Wall Street. He also opposed American entry into the World Court. This and Long's radical populist rhetoric and his aggressive tactics did little to endear him to his fellow senators. Not one of his proposed bills, resolutions or motions was passed during his three years in the Senate despite an overwhelming Democratic majority. During one debate, another senator told Long, "I do not believe you could get the Lord's Prayer endorsed in this body."[130] Despite the senators' distaste for Long's rhetoric, Long often praised his colleagues, whom he called "ninety-six men of varied and sundry political complexions, informed on all subjects and questions, separately and collectively, far better than I had ever expected any ninety-odd men to be. Within a few days I found in that body the uncurbed kind of versatile intelligence which will be the bulwark of support to democratic governments in the United States for trying centuries to come."[131]

Share Our Wealth

Long strongly opposed the Federal Reserve System. Together with a group of House members and senators, Long claimed that the Federal Reserve's policies were the true cause of the Great Depression. Long made speeches denouncing the large banking houses of Morgan and Rockefeller centered in New York City, which owned stock in the Federal Reserve. He believed that these large bankers manipulated the monetary system to their own benefit, instead of that of the general public.[132]

In March 1933, Long offered a series of bills collectively known as "the Long plan" for the redistribution of wealth. The first bill proposed a new progressive tax code designed to cap personal fortunes at $100 million. Fortunes above $1 million would be taxed at 1 percent; fortunes above $2 million would be taxed at 2 percent, and so forth, up to a 100 percent tax on fortunes greater than $100 million. The second bill limited annual income to $1 million, and the third bill capped individual inheritances at $5 million.[133]

In February 1934, Long introduced his Share Our Wealth plan over a nationwide radio broadcast.[134] He proposed capping personal fortunes at $50 million and repeated his call to limit annual income to $1 million and inheritances to $5 million. (He also suggested reducing the cap on personal fortunes to $10 million–$15 million per individual, if necessary, and later lowered the cap to $5 million–$8 million in printed materials.) The resulting funds would be used to guarantee every family a basic household grant, or "household estate" as Long called it, of $5,000 and a minimum annual income of $2,000–3,000, or one-third of the average family homestead value and income. Long supplemented his plan with proposals for free college education[note 1] and vocational training for all able students, old-age pensions, veterans' benefits, federal assistance to farmers, public works projects, greater federal regulation of economic activity, a month's vacation for every worker, and limiting the work week to thirty hours to boost employment.[136] He proposed a $10 billion land reclamation project to end the Dust Bowl. Long also promised free medical service and what he called a "war on disease" led by the Mayo brothers.[137] In his speech, Long used populist language depicting the U.S. past as a lost paradise stolen by the rich, saying:

God invited us all to come and eat and drink all we wanted. He smiled on our land and we grew crops of plenty to eat and wear. He showed us in the earth the iron and other things to make everything we wanted. He unfolded to us the secrets of science so that our work might be easy. God called: 'Come to my feast.' Then what happened? Rockefeller, Morgan, and their crowd stepped up and took enough for 120 million people and left only enough for 5 million for all the other 125 million to eat. And so many millions must go hungry and without these good things God gave us unless we call on them to put some of it back.[134][138]

— The ending of Long's autobiography, in which he muses on the future success of his "Share Our Wealth" program[139]

Long's plans for the "Share Our Wealth" program attracted much criticism from economists at the time, who stated that Long's plans for redistributing wealth would not result in every American family receiving a grant of $5,000 per year, but rather $400/per year, and that his plans for confiscatory taxation would cap the average annual income at about $3,000.[140] In 1934, Long held a public debate with Norman Thomas, the leader of the Socialist Party of America, on the merits of Share Our Wealth versus socialism.[141]

With the Senate unwilling to support his proposals, in February 1934 Long formed a national political organization, the Share Our Wealth Society. A network of local clubs led by national organizer Reverend Gerald L. K. Smith, the Share Our Wealth Society was intended to operate outside of and in opposition to the Democratic Party and the Roosevelt administration. By 1935, the society had over 7.5 million members in 27,000 clubs across the country. Long's Senate office received an average of 60,000 letters a week.[142] Long's newspaper American Progress averaged a circulation of 300,000, with some issues reaching 1.5 million.[113]

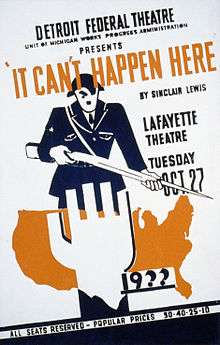

Some historians believe that pressure from Long and his organization contributed to Roosevelt's "turn to the left" in 1935. He enacted the Second New Deal, including the Social Security Act, the Works Progress Administration, the National Labor Relations Board, Aid to Dependent Children, the National Youth Administration, and the Wealth Tax Act of 1935. In private, Roosevelt candidly admitted to trying to "steal Long's thunder."[142]

Continued control over Louisiana (1932–35)

Long continued to maintain effective control of Louisiana while he was a senator, blurring the boundary between federal and state politics. Though he had no constitutional authority to do so, Long continued to draft and press bills through the Louisiana State Legislature, which remained in the hands of his allies. He made frequent trips to Baton Rouge to pressure the legislature into enacting his legislation. The program included new consumer taxes, elimination of the poll tax, a homestead tax exemption, and increases in the number of state employees. While physically in Louisiana, Long customarily stayed at the Roosevelt Hotel in New Orleans, where he was fond of the Sazerac Bar (see Peychaud's Bitters). According to Thomas M. Mahne in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, Long had a personal interest in seeing to the quick construction of Airline Highway (US 61) between Baton Rouge and New Orleans as the new road cut 40 miles from the trip.[143]

Long's loyal lieutenant, Governor Oscar K. Allen, dutifully enacted Long's policies. Long berated the governor in public and took over the governor's office in the State Capitol when visiting Baton Rouge.[144] On occasion, he even entered the legislative chambers, going so far as to sit on representatives' and senators' desks and sternly lecture them on his positions.[145] He also retaliated against those who voted against him and used patronage and state funding (especially highways) to maneuver Louisiana toward what opponents called a Long "dictatorship".[146][147] Having broken a second time after earlier reconciliation with the Old Regulars and Mayor Walmsley in the fall of 1933, Long inserted himself into the New Orleans mayoral election of 1934. A second rift hence developed with the city government that lasted even until after Long's assassination.[148]

In 1934, Long and James A. Noe, an independent oilman and member of the Louisiana Senate from Ouachita Parish, formed the controversial Win or Lose Oil Company. The firm was established to obtain leases on state-owned lands so that its directors might collect bonuses and sublease the mineral rights to the major oil companies. Although ruled legal, these activities were done in secret, and the stockholders were unknown to the public. Long made a profit on the bonuses and the resale of those state leases and used the funds primarily for political purposes.[149]

By 1934, Long began a reorganization of the state government that reduced the authority of local governments in anti-Long strongholds New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Alexandria. It further gave the governor the power to appoint all state employees.[150] Long passed what he called "a tax on lying" and a 2 percent tax on newspaper advertising revenue.[151] He created the Bureau of Criminal Identification, a special force of plainclothes police answerable only to the governor. He also had the legislature enact the same tax on refined oil that in 1929 had nearly led to his impeachment, which he used as a bargaining chip to promote oil drilling in Louisiana. After Standard Oil agreed that 80 percent of the oil sent to its refineries would be drilled in Louisiana, Long's government refunded most of these tax revenues.

1935: Long's final year

Presidential ambitions

Even during his days as a traveling salesman, Long had confided to his wife that his planned career trajectory would begin with election to a minor state office, then governor, then senator, and ultimately President of the United States. By the mid 1930s, he had greatly risen in stature to become a national figure. By the summer of 1935, Long's Share Our Wealth clubs had 7.5 million members nationwide, he regularly garnered 25 million radio listeners, and he was receiving 60,000 letters a week from supporters (more than the president).[152] In his final months, Long followed up his earlier autobiography, Every Man a King, with a second book titled My First Days in the White House, laying out his plans for the presidency after the election of 1936. The book was published posthumously.[153]

Long biographers T. Harry Williams and William Ivy Hair speculated that Long planned to challenge Roosevelt for the Democratic nomination in 1936, knowing he would lose the nomination but gain valuable publicity in the process. Then he would break from the Democrats and form a third party using the Share Our Wealth plan as its basis. He also hoped to have the public support of Father Charles Coughlin, a Catholic priest and populist talk radio personality from Royal Oak, Michigan; Iowa agrarian radical Milo Reno; and other dissidents like Francis Townsend and the remnants of the End Poverty In California movement.[154]

Long said of Coughlin that: "Father Coughlin has a damned good platform and I'm 100% percent for him ... What he thinks is right down my alley".[155] In Wisconsin, the Progressive newspaper in an editorial stated that the editors did not agree "with every conclusion reached by Father Coughlin and Senator Long, but when they contend ... that the tremendous wealth of this country should be more equitably shared for a more abundant life for the masses of the people, we agree heartily with them".[155]

Some historians, including Long biographer T. Harry Williams, contend that Long had never intended to run for the presidency in 1936. Instead, he had been plotting with Coughlin to run someone else on the soon-to-be-formed "Share Our Wealth" Party ticket. According to Williams, the idea was that this candidate would split the left-wing vote with Roosevelt, thereby electing a Republican president and proving the electoral appeal of Share Our Wealth. Long would then wait four years and run for president as a Democrat in 1940.

In spring 1935, Long undertook a national speaking tour and regular radio appearances, attracting large crowds and increasing his stature.[156] At a rally of the Farmers Holiday Association in Des Moines, Long was introduced by Reno and asked the crowd: "Do you believe in the redistribution of wealth?", receiving a huge "Yes!" as a response.[157] After the rally, Long was heard to say that: "I could take this state like a whirlwind".[157] At a well attended Long rally in Philadelphia, a former mayor told the press "There are 250,000 Long votes" in this city.[157]

The Roosevelt administration was worried by Long's growing popularity and on March 4, 1935, General Hugh S. Johnson in a radio speech denounced Long and Coughlin as this "great Louisiana demagogue and this political padre", going on to accuse the duo of speaking "with nothing of learning, knowledge nor experience to lead us through a labyrinth that has perplexed the minds of men since the beginning of time ... These two men are raging up and down this land preaching not construction, but destruction – not reform, but revolution!".[157] Democratic National Committee Chairman James Farley commissioned a secret poll in early 1935 "to find out if Huey's sales talks for his 'share the wealth' program were attracting many customers ... We kept a careful eye on what Huey and his political allies ... were attempting to do".[155]

Farley's poll revealed that if Long ran on a third-party ticket, he would win about 4 million votes (about 10% of the electorate).[158] In a memo to Roosevelt, Farley wrote: "It was easy to conceive of a situation whereby Long by polling more than 3,000,000 votes, might have the balance of power in the 1936 election. For example, the poll indicated that he would command upwards of 100,000 votes in New York State, a pivotal state in any national election and a vote of that size could easily mean the difference between victory and defeat ... That number of votes would mostly come from our side and the result might spell disaster".[158]

In response, Roosevelt in a letter to his friend William E. Dodd, who was serving as American ambassador in Berlin, wrote: "Long plans to be a candidate of the Hitler type for the presidency in 1936. He thinks he will have a hundred votes at the Democratic convention. Then he will set up as an independent with Southern and mid-western Progressives ... Thus he hopes to defeat the Democratic Party and put in a reactionary Republican. That would bring the country to such a state by 1940 that Long thinks he would be made dictator. There are in fact some Southerners looking that way, and some Progressives drifting that way ... Thus it is an ominous situation".[158]

Increased tensions in Louisiana

By 1935, Long's most recent consolidation of personal power led to talk of armed opposition from his enemies. Opponents increasingly invoked the memory of the Battle of Liberty Place of 1874, in which the White League staged an uprising against Louisiana's Reconstruction-era government. In January 1935, an anti-Long paramilitary organization called the Square Deal Association was formed. Its members included former governors John M. Parker and Ruffin G. Pleasant and New Orleans Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley.[159]

On January 25, 1935, armed Square Dealers took over the courthouse of East Baton Rouge Parish. Long had Governor Allen call out the National Guard, declare martial law, ban public gatherings of two or more persons, and forbid the publication of criticism of state officials. The Square Dealers left the courthouse, but there was a brief armed skirmish at the Baton Rouge Airport. Tear gas and live ammunition were fired; one person was wounded but there were no fatalities.[159]

In the summer of 1935, Long called for two more special sessions of the legislature; bills were passed in rapid-fire succession without being read or discussed. The new laws further centralized Long's control over the state by creating several new Long-appointed state agencies: a state bond and tax board holding sole authority to approve all loans to parish and municipal governments, a new state printing board which could withhold "official printer" status from uncooperative newspapers, a new board of election supervisors which would appoint all poll watchers, and a State Board of Censors. They also stripped away the remaining lucrative powers of the mayor of New Orleans, to cripple the entrenched opposition. Long boasted that he had "taken over every board and commission in New Orleans except the Community Chest and the Red Cross."[160]

Long also quarreled with former State Senator Henry E. Hardtner of La Salle Parish. While proceeding to Baton Rouge in August 1935 to confront the state government over a tax matter relating to his Urania Lumber Company, based in Urania, Hardtner, known as "the father of forestry in the South," was killed in a car-train accident.[161]

Assassination

Shooting and aftermath

Long had previously acknowledged the possibility of his own death.[162] In a 1935 speech, he claimed that his political enemies had a plot to kill him with "one man, one gun, one bullet."[163] Long had even sensationally claimed that Chicago gangsters were after him.[164]

On Sunday morning, September 8, 1935, Long left his twelfth floor suite at the Roosevelt Hotel. While leaving, the hotel's owner Seymour Weiss[note 2] asked Long where the deduct box[note 3] was. Long replied, "I'll tell you later, Seymour." The deduct box was never found.[86] Long travelled to the State Capitol in order to pass House Bill Number One,” a re-redistricting plan, which would oust political opponent Judge Benjamin Henry Pavy.[165]

At 9:20 p.m., just after passage of the bill effectively removing Pavy, Pavy's son-in-law Carl Weiss approached Long, and, according to the generally accepted version of events, fired a single shot with a handgun from four feet (1.2 m) away. Long was struck in the torso. Long's bodyguards, nicknamed the "Cossacks" or "skullcrushers",[166] responded by firing at Weiss with their own pistols, killing him; an autopsy found that Weiss had been shot more than sixty times by Long's bodyguards.[167] Long was able to run down a flight of stairs and across the capitol grounds, hailing a car to take him to the Our Lady of the Lake Hospital.[163]

The assassin Weiss was a well respected 29 year-old ear, nose, and throat specialist from Baton Rouge. His father was president of the Louisiana Medical Society.[168] Weiss was not involved in politics and had just had a son with his wife Yvonne, the daughter of Judge Pavy.[166][163] It was rumored that Long referred to the Pavy's as having "Negro blood", possibly motivating Weiss,[169] but there is no written record of Long saying that.[168] Weiss owned a gun, which he often carried with him during house-calls, a common practice at the time.[166] Weiss' house was not searched by the authorities after the shooting and there is no evidence that he planned the killing.[163]

Long was rushed to the hospital, where emergency surgery attempted to close perforations in his intestines, but ultimately failed in trying to stop his internal bleeding.[163][165] Long died 31 hours later on Tuesday, September 10 at 4:10 a.m.[170][167] According to different sources, his last words were either, "I wonder what will happen to my poor university boys" or "God, don’t let me die. I have so much to do".[171][165] There has been controversy about whether Long could have survived with better surgical care.[172] Biographer T. Harry Williams concluded that Long died as a result of medical incompetence.[170] An autopsy was not conducted on Long or Weiss.[173]

Long's body, dressed in a tuxedo, lay in an open double casket (of bronze with a glass lid) in the State Capitol rotunda. Some 200,000 people entered Baton Rouge for his funeral.[167] Tens of thousands saw the funeral in front of the Capitol on September 12;[174] presiding was Gerald L. K. Smith, co-founder of Share Our Wealth and subsequently of the America First Party.[175][176] Long was buried on the grounds of the new State Capitol, and a statue at his grave depicts his achievements.[166] Within the Capitol, a plaque marks the site of the assassination.[163]

On September 16, 1935, an inquest was held by the state authorities. Only fervent Longites were allowed to testify, including a judge who hadn't even witnessed the shooting. No ballistic or medical evidence was examined.[168] Long's allies in the Democratic Party quickly took advantage of the situation. Insinuating that Long's assassination was part of a larger conspiracy, they labelled their opponents the "Assassination Party". They published a 50 page propaganda pamphlet: "Why Huey Long Was Killed!!" However, a federal probe found no evidence of a political conspiracy.[170]

Countertheory

Although most believe that Weiss did confront Long, some claim that he only punched Long. Nurse Jewel O’Neal was one of those who helped treat the dying Long. In a 1935 affidavit, she claimed that while treating Long's bruised lip, he told her "That’s where he hit me."[168] Proponents of this theory claim that Long was caught in the cross fire as his bodyguards shot Weiss, and was hit by one of the bullets which ricocheted off the marble walls.[166][177]

Francis Grevemberg, head of the Louisiana State Police in the 1950s, claimed in an affidavit that during a 1953 gambling raid, he heard three state troopers say that bodyguards Joe Messina and Murphy Roden opened fire on Weiss after he punched Long. He also claimed that one of Long's former security guards told him that Weiss's gun was removed from his car and planted at the scene. Grevemberg claims he was told not to investigate.[170][168] Delmas Sharp Jr., the son of one of Long's bodyguards, claimed that in 1951 his father brought him to a bar owned by Messina. He stated that his father identified Messina as the man who killed Long. Messina turned his back on his colleague but did not deny the claim.[168]

In his 1986 book Requiem for a Kingfish: The Strange and Unexplained Death of Huey Long, Ed Reed claimed that two bullets, not one, were found in Long's body. He relied on testimony from Long's mortician, who claimed that a doctor returned late at night to remove an additional bullet from Long's corpse.[170] This was not the only discrepancy. Weiss’ brother, Tom Ed Weiss, who arrived at the scene an hour after the shooting, claimed that Weiss' car had been moved from where witnesses had seen it at the door of the Capitol and that his brother’s gun had been removed from the glove compartment. Additionally, the coroner did not find car keys in Weiss’s pockets.[168]

Weiss' son, Carl Weiss Jr. believed his father to be innocent: "I don't believe that he fired a fatal shot or indeed that he carried a gun into the state Capitol that night." In a 1985 conversation with Long's son Russell, Weiss learned of the existence of his father's gun. With James Starrs of George Washington University, Weiss located the gun in a New Orleans safe-deposit box, owned by Mabel Guerre Binnings, the daughter of Louis Guerre, the state's head of crime investigations in 1935. After a legal battle, she gave up possession of the box in 1991. It contained Weiss' .32 caliber automatic pistol, a .32 caliber bullet that had been fired and had a blunt tip from an impact, and photos of Long's clothing, showing a single bullet hole. After firing a test bullet, State Police investigators concluded that the bullet was not fired by Weiss' gun. However, it could not have been from one of the bodyguards as they carried a larger caliber.[170]

As Weiss was never given an autopsy, his body was exhumed in 1991.[173][178] His remains were examined at the Smithsonian Institution's Museum of Natural History. Although nearly all soft-tissue had decomposed, pathologists were able to study his damaged bones. They concluded that at least 24 bullets struck Weiss, conflicting with eyewitness accounts of at least 60. This discrepancy is likely due to most bullets passing through soft-tissue and missing Weiss' bones. They were also able to determine the angle of impact of each bullet: Weiss was shot front the front 7 times, thrice from the right, twice from the left, and 12 times from behind. This indicates that Weiss was killed in an erratic crossfire. A .38 calibre slug was found in Weiss' skull, having entered below his left eye. According to ballistics expert Lucien C. Haag, a bullet of this size should have had enough energy to exit the skull. He claimed that this lack of force was indicative of it passing through another body. It is believed that this bullet passed through Weiss' arm: suit fiber was attached to the bullet and there was damage to bones in Weiss' arms. Starrs claims that this suggests that Weiss was in a "defensive posture", with arms raised before him.[166]

After the assassination, the MONY Life Insurance Co. dispatched company investigator K. B. Ponder to validate the nature of Long's death. His 1935 report concluded:

There is no doubt that Weiss attacked Long, but there is considerable doubt that Weiss ever fired a gun. ... There is no doubt that his death was accidental, but the consensus of more informed opinion is that he was killed by his own guard and not by Weiss.[170]

In determining that Long's death was accidental, MONY paid a $20,000 life insurance claim to Long's widow. This information was only publicly released in 1985, 50 years after Long's death.[170]

Social and political positions

Communism