History of the Jews in Malta

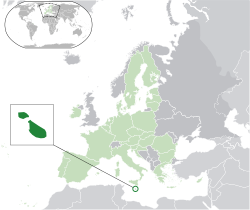

The history of the Jews in Malta can be traced back to approximately 62 CE. Most contemporary Maltese Jews are Sephardic, however an Ashkenazic prayer book is used.[1]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Malta |

|

|

Modern history |

|

|

|

Antiquity

The first Jew known to have set foot on Malta was Paul of Tarsus, whose ship foundered there in 62 CE.[2] Paul went on to introduce Christianity to the island population.[3]

Greek inscriptions and menorah-decorated tombs indicate that Jews and early Christians lived on Malta during the 4th and 5th centuries.[4][5] During the Fatimid Caliphate rule of the island, Jews often held posts as civil servants; one member of the community even reaching the highest possible rank, Vizier.

Middle Ages

The Jewish population of Malta peaked in the Middle Ages under Norman rule. The Normans occupied the islands from 1091, with five hundred Jews living on the main island and 350 on the sister island, Gozo. The Jewish people generally prospered during this period and were not required to live in ghettos. Most owned agricultural land or worked as merchants. Avraham Abulafia, a well-known Jewish mystic, lived on Comino from 1285 to his death in the 1290s. In 1479 Malta and Sicily came under Aragonese rule and the 1492 Edict of Expulsion forced all Jews to leave the country. Because they made up such a large portion of the island's population the Spanish Crown forced them to pay compensation for the losses caused by their expulsion.

It is not clear where the Jews of Malta went, but they may have joined the Sicilian community in Levant. It is also likely that several dozen Maltese Jews converted to Christianity to remain in the country as did many Sicilian Jews. This is further evidenced by the large number of Maltese surnames thought to be of Jewish origin.[1][6]

Renaissance

In 1530 Charles V of Spain gave Malta to the Knights of Saint John. The Knights ruled the island until 1798; many Sicilian conversos then moved here remembering the Knights' liberal policy towards the Jews of Rhodes, but they had to continue practicing their religion in secrecy.[6] Jews volunteered for the desperate attempt to relieve Fort St Elmo during the Great Siege (No proof of this at source link).[1] Following this, there was no free Jewish population in the country during the Knights' reign. The Knights would often take passengers of merchant ships - including numerous Jews - hostage in order to get the ransom and it would be up to Jewish Societies for the Redemption of Captives to raise it. There were therefore many Jewish slaves in Malta during this period and Malta was frequently mentioned for its large enslaved Jewish population in Jewish literature of the period.[7] Free Jews wishing to visit the country could only enter through one port in Valletta, which is still known as the Jews' Sallyport.

Modern

The majority of the contemporary Maltese Jewish community originates in Jewish immigration from Gibraltar, England, North Africa, Portugal and Turkey during the short period of French rule from 1798 to 1800 and British rule after that. From 1805 Jews were the targets of campaigns by the Maltese directed at all foreigners.[7] In 1846, a Tripolitanian became the country's first modern rabbi.

During the early 20th century, the island did not always have a rabbi of its own and rabbis would be flown in from Sicily to perform ceremonies.[8] In the time before World War II many Jews fleeing Nazism came to Malta as it was the only European country not to require visas of Jews fleeing German rule.[7] Numerous Maltese Jews fought Germany in the British Army during the war.

Today, 1,000 Jews live in Malta, of which many are elderly due to the tendency of young inhabitants to emigrate. Maltese Jews live mainly around the capital.[1] The local flat bread called ftira and the traditional Maltese loaf are both kosher.[1]

In 2000, a new synagogue was built with donations from the United States and the UK. The Jewish Foundation of Malta now manages it along with a Jewish Center.[8] Malta's relations with Israel have been friendly since the former's independence.

Official recognition of Judaism

Judaism, along with Hinduism, is recognised as a cult but not as a religion in Malta. In 2010, Hindu and Jewish groups urged Pope Benedict XVI to intervene to ensure that Malta treats all religions equally before the law.[9], but the Pope did not intervene. Rajan Zed, president of the Universal Society of Hinduism, and Rabbi Jonathan B. Freirich, a Jewish leader in California and Nevada in the US, said in a statement in Nevada that he believed the Catholic Church in Malta was not serious about sharing the minority religious viewpoint, and that he was disappointed that they did not want to discuss issues of religious equality with minority religions and denominations.[10]

References

- "Message". Jewsofmalta.org. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- "The Apostle Paul's Shipwreck | Evidence and Paul's Journeys". Parsagard.com. Archived from the original on 2015-02-17. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- "Notable Dates in Malta's History". Department of Information, Malta. Archived from the original on November 25, 2009.

- Noy, David (2005). Jewish Inscriptions of Western Europe, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-521-61977-6.

- Hachlili, Rachel (1998). Ancient Jewish art and archaeology in the diaspora, Volume 35. Brill. p. 383. ISBN 978-90-04-10878-3.

- "Malta Virtual Jewish History Tour". Jewish Virtual Library. 2013-10-15. Retrieved 2015-12-22.

- Hecht, Esther: The Jewish Traveler: Malta in Hadassah Magazine. December 2005. Accessed December 28, 2006.

- "The Jews of Malta - Beit Hatfutsot". bh.org.il.

- "Hindus seek Pope's intervention to bring equality of religions in Malta". Timesofmalta.com. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- "Pope Disappoints members of the Hindu and Jewish Community - ChakraNews.com". chakranews.com. 19 February 2010.