Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem was any of a series of structures which were located on the Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusalem, the current site of the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque. These successive temples stood at this location and functioned as a site of ancient Israelite and later Jewish worship. It is also called the Holy Temple (Hebrew: בֵּית־הַמִּקְדָּשׁ, Modern: Bēt HaMīqdaš, Tiberian: Bēṯ HaMīqdāš, Ashkenazi: Bēs HaMīqdoš; Arabic: بيت المقدس Beit al-Maqdis; Ge'ez: ቤተ መቅደስ: Betä Mäqdäs).

| Part of a series on |

| Jerusalem |

|---|

-Aerial-Temple_Mount-(south_exposure).jpg) |

| Sieges |

| Places |

| Political status |

| Other topics |

Etymology

The Hebrew name given in the Hebrew Bible for the building complex is either Beit YHWH "House of YHWH", Beit HaElohim "House of God", or simply Beiti "my house", Beitekhah "your house" etc.[1]

In rabbinical literature the temple is Beit HaMikdash, "The Sanctified House", and only the Temple in Jerusalem is referred to by this name.[1]

First Temple

The Hebrew Bible says that the First Temple was built by King Solomon.[2] According to the Book of Deuteronomy, as the sole place of Israelite sacrifice (Deuteronomy 12:2-27), the Temple replaced the Tabernacle constructed in the Sinai Desert under the auspices of Moses, as well as local sanctuaries, and altars in the hills.[3] This temple was sacked a few decades later by Shoshenq I, Pharaoh of Egypt.[4]

Although efforts were made at partial reconstruction, it was only in 835 BCE when Jehoash, King of Judah, in the second year of his reign invested considerable sums in reconstruction, only to have it stripped again for Sennacherib, King of Assyria c. 700 BCE. The First Temple was totally destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BCE, when they sacked the city.[5]

Second Temple

According to the Book of Ezra, construction of the Second Temple was called for by Cyrus the Great and began in 538 BCE,[6] after the fall of the Babylonian Empire the year before.[7] According to some 19th-century calculations, work started later, in April 536 BCE (Haggai 1:15), and was completed in 515 BCE - February 21 - 21 years after the start of the construction. This date is obtained by coordinating Ezra 3:8-10 (the third day of Adar, in the sixth year of the reign of Darius the Great) with historical sources.[8] The accuracy of these dates is contested by modern researchers, who consider the biblical text to be of later date and based on a combination of historical records and religious considerations, leading to contradictions between different books of the Bible and making the dates unreliable.[9] The new temple was dedicated by the Jewish governor Zerubbabel. However, with a full reading of the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah, there were four edicts to build the Second Temple, which were issued by three kings: Cyrus in 536 BCE (Ezra ch. 1), Darius I of Persia in 519 BCE (ch. 6), and Artaxerxes I of Persia in 457 BCE (ch. 7), and finally by Artaxerxes again in 444 BCE (Nehemiah ch. 2).[10] Also, despite the fact that the new temple was not as extravagant or imposing as its predecessor, it still dominated the Jerusalem skyline and remained an important structure throughout the time of Persian suzerainty.

The temple narrowly avoided being destroyed again in 332 BCE when the Jews refused to acknowledge the deification of Alexander the Great of Macedonia. Alexander was allegedly "turned from his anger" at the last minute by astute diplomacy and flattery. Further, after the death of Alexander on 13 June 323 BCE, and the dismembering of his empire, the Ptolemies came to rule over Judea and the Temple. Under the Ptolemies, the Jews were given many civil liberties and lived content under their rule. However, when the Ptolemaic army was defeated at Panium by Antiochus III of the Seleucids in 200 BCE, this policy changed. Antiochus wanted to Hellenise the Jews, attempting to introduce the Greek pantheon into the temple. Moreover, a rebellion ensued and was brutally crushed, but no further action by Antiochus was taken, and when Antiochus died in 187 BCE at Luristan, his son Seleucus IV Philopator succeeded him. However, his policies never took effect in Judea, since he was assassinated the year after his ascension. Antiochus IV Epiphanes succeeded his older brother to the Seleucid throne and immediately adopted his father's previous policy of universal Hellenisation. The Jews rebelled again and Antiochus, in a rage, retaliated in force. Considering the previous episodes of discontent, the Jews became incensed when the religious observances of Sabbath and circumcision were officially outlawed. When Antiochus erected a statue of Zeus in their temple and Hellenic priests began sacrificing pigs (the usual sacrifice offered to the Greek gods in the Hellenic religion), their anger began to spiral. When a Greek official ordered a Jewish priest to perform a Hellenic sacrifice, the priest (Mattathias) killed him. In 167 BCE, the Jews rose up en masse behind Mattathias and his five sons to fight and win their freedom from Seleucid authority. Mattathias' son Judah Maccabee, now called "The Hammer", re-dedicated the temple in 165 BCE and the Jews celebrate this event to this day as the central theme of the non-biblical festival of Hanukkah. The temple was rededicated under Judah Maccabee in 164 BCE.[2]

During the Roman era, Pompey entered (and thereby desecrated) the Holy of Holies in 63 BCE, but left the Temple intact.[11][12][13] In 54 BCE, Crassus looted the Temple treasury,[14][15] only for him to die the year after at the Battle of Carrhae against Parthia. According to folklore he was executed by having molten gold poured down his throat. When news of this reached the Jews, they revolted again, only to be put down in 43 BCE.

Around 20 BCE, the building was renovated and expanded by Herod the Great, and became known as Herod's Temple. It was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE during the Siege of Jerusalem. During the Bar Kokhba revolt against the Romans in 132–135 CE, Simon bar Kokhba and Rabbi Akiva wanted to rebuild the Temple, but bar Kokhba's revolt failed and the Jews were banned from Jerusalem (except for Tisha B'Av) by the Roman Empire. The emperor Julian allowed to have the Temple rebuilt but the Galilee earthquake of 363 ended all attempts ever since.

After the Muslim conquest of Jerusalem in the 7th century, Umayyad Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan ordered the construction of an Islamic shrine, the Dome of the Rock, on the Temple Mount. The shrine has stood on the mount since 691 CE; the al-Aqsa Mosque, from roughly the same period, also stands in what used to be the Temple courtyard.

Recent history

The Temple Mount, along with the entire Old City of Jerusalem, was captured from Jordan by Israel in 1967 during the Six-Day War, allowing Jews once again to visit the holy site.[16][17] Jordan had occupied East Jerusalem and the Temple Mount immediately following Israel's declaration of independence on May 14, 1948. Israel officially unified East Jerusalem, including the Temple Mount, with the rest of Jerusalem in 1980 under the Jerusalem Law, though United Nations Security Council Resolution 478 declared the Jerusalem Law to be in violation of international law.[18] The Muslim Waqf, based in Jordan, has administrative control of the Temple Mount.

Location

There are three main theories as to where the Temple stood: where the Dome of the Rock is now located, to the north of the Dome of the Rock (Professor Asher Kaufman), or to the east of the Dome of the Rock (Professor Joseph Patrich of the Hebrew University).[19]

The exact location of the Temple is a contentious issue, as elements of questioning the exact placement of the Temple is often associated with Temple denial. Since the Holy of Holies lay at the center of the complex as a whole, the Temple's location is obviously connected with the location of the Holy of Holies. The location of the Temple was even a question less than 150 years after the Second Temple's destruction, as detailed in the Talmud. Chapter 54 of the Tractate Berakhot states that the Holy of Holies was directly aligned with the Golden Gate, which would have placed the Temple slightly to the north of the Dome of the Rock, as Kaufman postulated.[20] However, chapter 54 of the Tractate Yoma and chapter 26 of the Tractate Sanhedrin asserts that the Holy of Holies stood directly on the Foundation Stone, which agrees with the consensus theory that the Dome of the Rock stands on the Temple's location.[21][22]

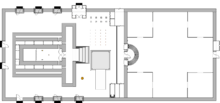

Physical layout

The Temple of Solomon or First Temple consisted of three main elements:

- the Great or Outer Court, where people assembled to worship (Jeremiah 19:14; 26:2);

- the Inner Court (1 Kings 6:36) or Court of the Priests (2 Chr. 4:9);

- and the Temple building itself, with

- the larger hekhal, or Holy Place, called the "greater house" in 2 Chr. 3:5 and the "temple" in 1 Kings 6:17, and

- the smaller "inner sanctum", known as the Holy of Holies or Kodesh HaKodashim.

In the case of the last and most elaborate structure, the Herodian Temple, the structure consisted of the wider Temple precinct, the restricted Temple courts, and the Temple building itself:

- Temple precinct, located on the extended Temple Mount platform, and including the Court of the Gentiles

- Court of the Women or Ezrat HaNashim

- Court of the Israelites, reserved for ritually pure Jewish men

- Court of the Priests, whose relation to the Temple Court is interpreted in different ways by scholars

- Temple Court or Azarah, with the Brazen Laver (kiyor), the Altar of Burnt Offerings (mizbe'ah), the Place of Slaughtering, and the Temple building itself

- The Temple edifice had three distinct chambers:

- Temple vestibule or porch (ulam)

- Temple sanctuary (hekhal or heikal), the main part of the building

- Holy of Holies (Kodesh HaKodashim or debir), the innermost chamber

According to the Talmud, the Women's Court was to the east and the main area of the Temple to the west.[23] The main area contained the butchering area for the sacrifices and the Outer Altar on which portions of most offerings were burned. An edifice contained the ulam (antechamber), the hekhal (the "sanctuary"), and the Holy of Holies. The sanctuary and the Holy of Holies were separated by a wall in the First Temple and by two curtains in the Second Temple. The sanctuary contained the seven branched candlestick, the table of showbread and the Incense Altar.

The main courtyard had thirteen gates. On the south side, beginning with the southwest corner, there were four gates:

- Shaar Ha'Elyon (the Upper Gate)

- Shaar HaDelek (the Kindling Gate), where wood was brought in

- Shaar HaBechorot (the Gate of Firstborns), where people with first-born animal offerings entered

- Shaar HaMayim (the Water Gate), where the Water Libation entered on Sukkot/the Feast of Tabernacles

On the north side, beginning with the northwest corner, there were four gates:

- Shaar Yechonyah (The Gate of Jeconiah), where kings of the Davidic line enter and Jeconiah left for the last time to captivity after being dethroned by the King of Babylon

- Shaar HaKorban (The gate of the Offering), where priests entered with kodshei kodashim offerings

- Shaar HaNashim (The Women's Gate), where women entered into the Azara or main courtyard to perform offerings[24]

- Shaar Hashir (The Gate of Song), where the Levites entered with their musical instruments

On the east side was Shaar Nikanor, between the Women's Courtyard and the main Temple Courtyard, which had two minor doorways, one on its right and one on its left. On the western wall, which was relatively unimportant, there were two gates that did not have any name.

The Mishnah lists concentric circles of holiness surrounding the Temple: Holy of Holies; Sanctuary; Vestibule; Court of the Priests; Court of the Israelites; Court of the Women; Temple Mount; the walled city of Jerusalem; all the walled cities of the Land of Israel; and the borders of the Land of Israel.

Temple services

The Temple was the place where offerings described in the course of the Hebrew Bible were carried out, including daily morning and afternoon offerings and special offerings on Sabbath and Jewish holidays. Levites recited Psalms at appropriate moments during the offerings, including the Psalm of the Day, special psalms for the new month, and other occasions, the Hallel during major Jewish holidays, and psalms for special sacrifices such as the "Psalm for the Thanksgiving Offering" (Psalm 100).

As part of the daily offering, a prayer service was performed in the Temple which was used as the basis of the traditional Jewish (morning) service recited to this day, including well-known prayers such as the Shema, and the Priestly Blessing. The Mishna describes it as follows:

The superintendent said to them, bless one benediction! and they blessed, and read the Ten Commandments, and the Shema, "And it shall come to pass if you will hearken", and "And [God] spoke...". They pronounced three benedictions with the people present: "True and firm", and the "Avodah" "Accept, Lord our God, the service of your people Israel, and the fire-offerings of Israel and their prayer receive with favor. Blessed is He who receives the service of His people Israel with favor" (similar to what is today the 17th blessing of the Amidah), and the Priestly Blessing, and on the Sabbath they recited one blessing; "May He who causes His name to dwell in this House, cause to dwell among you love and brotherliness, peace and friendship" on behalf of the weekly Priestly Guard that departed.

In the Talmud

Seder Kodashim, the fifth order, or division, of the Mishnah (compiled between 200–220 CE), provides detailed descriptions and discussions of the religious laws connected with Temple service including the sacrifices, the Temple and its furnishings, as well as the priests who carried out the duties and ceremonies of its service. Tractates of the order deal with the sacrifices of animals, birds, and meal offerings, the laws of bringing a sacrifice, such as the sin offering and the guilt offering, and the laws of misappropriation of sacred property. In addition, the order contains a description of the Second Temple (tractate Middot), and a description and rules about the daily sacrifice service in the Temple (tractate Tamid).[25][26][27]

In the Babylonian Talmud, all the tractates have Gemara – rabbinical commentary and analysis – for all their chapters; some chapters of Tamid, and none on Middot and Kinnim. The Jerusalem Talmud has no Gemara on any of the tractates of Kodashim.[26][27]

The Talmud (Yoma 9b) describes traditional theological reasons for the destruction: "Why was the first Temple destroyed? Because the three cardinal sins were rampant in society: idol worship, licentiousness, and murder… And why then was the second Temple – wherein the society was involved in Torah, commandments and acts of kindness – destroyed? Because gratuitous hatred was rampant in society."[28][29]

Role in contemporary Jewish services

Part of the traditional Jewish morning service, the part surrounding the Shema prayer, is essentially unchanged from the daily worship service performed in the Temple. In addition, the Amidah prayer traditionally replaces the Temple's daily tamid and special-occasion Mussaf (additional) offerings (there are separate versions for the different types of sacrifices). They are recited during the times their corresponding offerings were performed in the Temple.

The Temple is mentioned extensively in Orthodox services. Conservative Judaism retains mentions of the Temple and its restoration, but removes references to the sacrifices. References to sacrifices on holidays are made in the past tense, and petitions for their restoration are removed. Mentions in Orthodox Jewish services include:

- A daily recital of Biblical and Talmudic passages related to the korbanot (sacrifices) performed in the Temple (See korbanot in siddur).

- References to the restoration of the Temple and sacrificial worships in the daily Amidah prayer, the central prayer in Judaism.

- A traditional personal plea for the restoration of the Temple at the end of private recitation of the Amidah.

- A prayer for the restoration of the "house of our lives" and the shekhinah (divine presence) "to dwell among us" is recited during the Amidah prayer.

- Recitation of the Psalm of the day; the psalm sung by the Levites in the Temple for that day during the daily morning service.

- Numerous psalms sung as part of the ordinary service make extensive references to the Temple and Temple worship.

- Recitation of the special Jewish holiday prayers for the restoration of the Temple and their offering, during the Mussaf services on Jewish holidays.

- An extensive recitation of the special Temple service for Yom Kippur during the service for that holiday.

- Special services for Sukkot (Hakafot) contain extensive (but generally obscure) references to the special Temple service performed on that day.

The destruction of the Temple is mourned on the Jewish fast day of Tisha B'Av. Three other minor fasts (Tenth of Tevet, 17th of Tammuz, and Third of Tishrei), also mourn events leading to or following the destruction of the Temple. There are also mourning practices which are observed at all times, for example, the requirement to leave part of the house unplastered.

Herzl's vision

In his novel The Old New Land, depicting the future Jewish State as he envisioned it, Theodor Herzl - founder of political Zionism - included a depiction of a rebuilt Jerusalem Temple. However, in Herzl's view, the Temple did not need to be built on the precise site where the old Temple stood and which is now taken up by the Muslim Al-Aqsa Mosque and Dome of the Rock - very sensitive holy sites. By locating the Temple at an unspecified different Jerusalem location, the Jewish state envisioned by Herzl avoids the extreme tension over this issue experienced in the actual Israel. Also, worship at the Temple envisioned by Herzl does not involve animal sacrifice, which was the main form of worship at the ancient Jerusalem Temple. Rather, the Temple depicted in Herzl's book is essentially just an especially big and ornate synagogue, holding the same kind of services as any other synagogue.

In other religions

Christianity

Jesus predicts the destruction of the Second Temple (Matthew 24:2) and allegorically compares his body to a Temple that will be torn down and raised up again in three days. This idea, of the Temple as the body of Christ, became a rich and multi-layered theme in medieval Christian thought (where Temple/body can be the heavenly body of Christ, the ecclesial body of the Church, and the Eucharistic body on the altar).[30]

Islam

The Temple Mount bears significance in Islam as it acted as a sanctuary for the Hebrew prophets and the Israelites. Islamic tradition says that a temple was first built on the Temple Mount by Jacob and later rebuilt by Solomon, the son of David. Traditionally referred to as the "Farthest Mosque" (al-masjid al-aqṣa' literally "utmost site of bowing (in worship)" though the term now refers specifically to the mosque in the southern wall of the compound which today is known simply as al-haram ash-sharīf "the noble sanctuary"), the site is seen as the destination of Muhammad's nightly travel (Isrā' ), one of the most significant events recounted in the Quran and the place of his ascent heavenwards thereafter (Mi'raj).

According to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University, Jerusalem (i.e., the Temple Mount) has the significance as a holy site/sanctuary ("haram") for Muslims primarily in three ways, the first two being connected to the Temple.[31] First, Muhammad (and his companions) prayed facing the Temple in Jerusalem (referred to as "Bayt Al-Maqdis", in the Hadiths) similar to the Jews before changing it to the Kaaba in Mecca sixteen months after arriving in Medina following the verses revealed (Sura 2:144, 149-150). Secondly, during the Meccan part of his life, he reported to have been to Jerusalem by night and prayed in the Temple, as the first part of his otherworldly journey (Isra and Mi'raj).

Imam Abdul Hadi Palazzi, leader of Italian Muslim Assembly, quotes the Quran to support Judaism's special connection to the Temple Mount. According to Palazzi, "The most authoritative Islamic sources affirm the Temples". He adds that Jerusalem is sacred to Muslims because of its prior holiness to Jews and its standing as home to the biblical prophets and kings David and Solomon, all of whom he says are sacred figures in Islam. He claims that the Quran "expressly recognizes that Jerusalem plays the same role for Jews that Mecca has for Muslims".[32]

In his 2007 book, The Fight for Jerusalem: Radical Islam, the West, and the Future of the Holy City, Dore Gold calls assertions that the Temple in Jerusalem never existed or was not located on the Mount "Temple Denial". David Hazony has described the phenomenon as "a campaign of intellectual erasure [by Palestinian leaders, writers, and scholars] ... aimed at undermining the Jewish claim to any part of the land" and compared the phenomenon to Holocaust denial.[33]

Archaeological evidence

Archaeological excavations have found remnants of both the First Temple and Second Temple. Among the artifacts of the First Temple are dozens of ritual immersion or baptismal pools in this area surrounding the Temple Mount,[34] as well as a large square platform identified by architectural archaeologist Leen Ritmeyer as likely being built by King Hezekiah c. 700 BCE as a gathering area in front of the Temple.

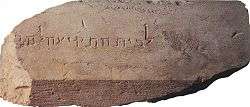

Possible Second Temple artifacts include the Trumpeting Place inscription and the Temple Warning inscription, which are surviving pieces of the Herodian expansion of the Temple Mount.

Building a Third Temple

Ever since the Second Temple's destruction, a prayer for the construction of a Third Temple has been a formal and mandatory part of the thrice-daily Jewish prayer services. However, the question of whether and when to construct the Third Temple is disputed both within the Jewish community and without; groups within Judaism argue both for and against construction of a new Temple, while the expansion of Abrahamic religion since the 1st century CE has made the issue contentious within Christian and Islamic thought as well. Furthermore, the complicated political status of Jerusalem makes reconstruction difficult, while Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock have been constructed at the traditional physical location of the Temple.

In 363 CE, the Roman emperor Julian had ordered Alypius of Antioch to rebuild the Temple as part of his campaign to strengthen non-Christian religions.[35] The attempt failed, perhaps due to sabotage, an accidental fire, or an earthquake in Galilee.

The Book of Ezekiel prophesies what would be the Third Temple, noting it as an eternal house of prayer and describing it in detail.

In media

A journalistic depiction of the controversies around the Jerusalem Temple was presented in the 2010 documentary Lost Temple by Serge Grankin. The film contains interviews with religious and academic authorities involved in the issue. German journalist Dirk-Martin Heinzelmann, featured in the film, presents the point of view of Prof. Joseph Patrich (the Hebrew University), stemming from the underground cistern mapping made by Charles William Wilson (1836-1905).[36]

See also

- Jewish Temple at Elephantine (7th? 6th? - mid-4th century BCE)

- Jewish Temple of Leontopolis (c. 170 BCE - 73 CE)

- Temple of Solomon (São Paulo), a replica built by a Brazil-based church

- Similar Iron Age temples from the region

References

- "The Jewish Temple (Beit HaMikdash)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2018-01-23.

- "Temple, the." Cross, F. L., ed. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. New York: Oxford University Press. 2005

- Durant, Will. Our Oriental Heritage. New York: Simon and Schuster. 1954. p. 307. See 1 Kings 3:2.

- Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, page 335, Oxford 2000

- New American Oxford Dictionary: "Temple".

- Shalem, Yisrael (1997). "Second Temple Period (538 B.C.E. to 70 C.E.): Persian Rule". Jerusalem: Life Throughout the Ages in a Holy City. Ramat-Gan, Israel: Ingeborg Rennert Center for Jerusalem Studies, Bar-Ilan University. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BCE. Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-1-107-00960-8. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Jamieson, Robert; Fausset, A. R.; Brown, David (1882). "Ezra 6:13-15. The Temple Finished". A Commentary, Critical, Practical, and Explanatory on the Old and New Testaments. Retrieved 8 January 2020 – via BibleHub.com.

- Edelman, Diana (2014). "The Seventy-Year Tradition Revisited". The Origins of the 'Second' Temple: Persion Imperial Policy and the Rebuilding of Jerusalem (reprint, revised ed.). Routledge. pp. 103–104. ISBN 978-1-84553-016-7. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- 'Abdu'l-Baha (ed.). Some Answered Questions. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Josephus, The New Complete Works, translated by William Whiston, Kregel Publications, 1999, "Antiquites" Book 14:4, p.459-460

- Michael Grant, The Jews in the Roman World, Barnes & Noble, 1973, p.54

- Peter Richardson, Herod: King of the Jews and Friend of the Romans, Univ. of South Carolina Press, 1996, p.98-99

- Josephus, The New Complete Works, translated by William Whiston, Kregel Publications, 1999, "Antiquites" Book 14:7, p.463

- Michael Grant, The Jews in the Roman World, Barnes & Noble, 1973, p.58

- "The Liberation of the Temple Mount and Western Wall (June 1967)". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- "1967: Reunification of Jerusalem". www.sixdaywar.org. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- Ibn Kathir (2008). "Stories of the Prophets", p. 164-165 (Hi by Rafiq Abdur Rahman, Idara Isha'at-e-diniyat publishers, India ed.). ISBN 81-7101-558-1.

- See article in the World Jewish Digest, April 2007

- Berakhot 54a:7

- Yoma 54b:2

- Sanhedrin 26b:5

- Mishna Tractate Midos.

- Sheyibaneh Beit Hamikdash: Women in the Azara? Archived 2006-07-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Birnbaum, Philip (1975). "Kodashim". A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York, NY: Hebrew Publishing Company. pp. 541–542. ISBN 088482876X.

- Epstein, Isidore, ed. (1948). "Introduction to Seder Kodashim". The Babylonian Talmud. vol. 5. Singer, M.H. (translator). London: The Soncino Press. pp. xvii–xxi.

- Arzi, Abraham (1978). "Kodashim". Encyclopedia Judaica. 10 (1st ed.). Jerusalem, Israel: Keter Publishing House Ltd. pp. 1126–1127.

- Gratuitous Hatred – What is it and Why is it so bad?

- "Hatred".

- See Jennifer A. Harris, "The Body as Temple in the High Middle Ages", in Albert I. Baumgarten ed., Sacrifice in Religious Experience, Leiden, 2002, pp. 233–256.

- "The Spiritual Significance of Jerusalem: The Islamic Vision. The Islamic Quarterly. 4 (1998): pp.233-242

- Margolis, David (February 23, 2001). "The Muslim Zionist". Los Angeles Jewish Journal.

- Hazony, David. "Temple Denial In the Holy City", The New York Sun, March 7, 2007.

- "Were there Jewish Temples on Temple Mount? Yes - Israel News". Haaretz.com. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 23.1.2–3.

- "Lost Temple". 1 January 2000 – via IMDb.

- Monson, John M. (June 1999). "The Temple of Solomon: Heart of Jerusalem". In Hess, Richard S. & Wenham, Gordon J. (eds.). Zion, city of our God. C.The Ain Dara Temple:A New Parallel from Syria. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 12–19. ISBN 978-0-8028-4426-2. Retrieved 15 February 2011.CS1 maint: uses editors parameter (link)

Further reading

- Biblical Archaeology Review, issues: July/August 1983, November/December 1989, March/April 1992, July/August 1999, September/October 1999, March/April 2000, September/October 2005

- Ritmeyer, Leen. The Quest: Revealing the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. Jerusalem: Carta, 2006. ISBN 965-220-628-8

- Hamblin, William and David Seely, Solomon's Temple: Myth and History (Thames and Hudson, 2007) ISBN 0-500-25133-9

- Yaron Eliav, God's Mountain: The Temple Mount in Time, Place and Memory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005)

- Rachel Elior, The Jerusalem Temple: The Representation of the Imperceptible, Studies in Spirituality 11 (2001), pp. 126–143

External links

- Visit of the Temple Institute Museum in Jerusalem conducted by Rav Israel Ariel

- Video tour of a model of the future temple described in Ezekiel chapters 40–49 from a Christian perspective

- Rachel Elior, "The Jerusalem Temple - The Representation of the Imperceptible", Studies in Spirituality 11 (2001): 126-143