History of submarines

Beginning in ancient times, mankind sought to operate under the water. From simple submersibles to nuclear-powered underwater behemoths, humans have searched for a means to remain safely underwater to gain the advantage in warfare, resulting in the development of the submarine.

Associated technology

Sensors

The first submarines had only a porthole to provide a view to aid navigation. An early periscope was patented by Simon Lake in 1893. The modern periscope was developed by the industrialist Sir Howard Grubb in the early 20th century and was fitted onto most Royal Navy designs.[47]

Passive sonar was introduced in submarines during the First World War, but active sonar ASDIC did not come into service until the inter-war period. Today, the submarine may have a wide variety of sonar arrays, from bow mounted to trailing ones. There are often upward-looking under-ice sonars as well as depth sounders.

Early experiments with the use of sound to 'echo locate' underwater in the same way as bats use sound for aerial navigation began in the late 19th century. The first patent for an underwater echo ranging device was filed by English meteorologist Lewis Richardson a month after the sinking of the Titanic.[48] The First World War stimulated research in this area. The British made early use of underwater hydrophones, while the French physicist Paul Langevin worked on the development of active sound devices for detecting submarines in 1915 using quartz. In 1916, under the British Board of Invention and Research, Canadian physicist Robert William Boyle took on the active sound detection project with A B Wood, producing a prototype for testing in mid-1917. This work, for the Anti-Submarine Division of the British Naval Staff, was undertaken in utmost secrecy, and used quartz piezoelectric crystals to produce the world's first practical underwater active sound detection apparatus.

By 1918, both France and Britain had built prototype active systems. The British tested their ASDIC on HMS Antrim in 1920, and started production in 1922. The 6th Destroyer Flotilla had ASDIC-equipped vessels in 1923. An anti-submarine school, HMS Osprey, and a training flotilla of four vessels were established on Portland in 1924. The US Sonar QB set arrived in 1931.

Weapons and countermeasures

Early submarines carried torpedoes mounted externally to the craft. Later designs incorporated the weapons into the internal structure of the submarine. Originally, both bow-mounted and stern-mounted tubes were used, but the latter eventually fell out of favour. Today, only bow-mounted installations are employed. The modern submarine is capable of firing many types of weapon from its launch tubes, including UAVs. Special mine laying submarines were also built. Up until the end of the Second World War, it was common to fit deck guns to submarines to allow them to sink ships without wasting their limited numbers of torpedoes.

To aid in the weapons targeting mechanical calculators were employed to improve the fire control of the on-board weaponry. The firing calculus was determined by the targets' course and speed through measurements of the angle and its range via the periscope. Today, these calculations are achieved by digital computers with display screens providing necessary information on the torpedo status and ship status.

German submarines in World War II had rubber coatings and could launch chemical devices to provide a decoy when the boat came under attack. These proved to be ineffective, as sonar operators learned to distinguish between the decoy and the submarine. Modern submarines can launch a variety of devices for the same purpose.

Safety

After the sinking of the A1 submarine in 1904, lifting eyes were fitted to British submarines and in 1908 air-locks and escape helmets were provided. The RN experimented with various types of escape apparatus, but it was not until 1924 that the "Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus" was developed for crew members. The USN used the similar "Momsen Lung". The French used "Joubert's apparatus" and the Germans used "Draeger's apparatus".

Rescue submarines for evacuating a disabled submarine's crew were developed in the 1970s. A British unmanned vehicle was used for recovering an entangled Russian submarine crew in 2005. A new NATO Submarine Rescue System entered service in 2007.

Communication and navigation

Wireless was used to provide communication to and from submarines in the First World War. The D-class submarine was the first submarine class to be fitted with wireless transmitters in 1907. With time the type, range and bandwidth of the communications systems have increased. With the danger of intercept, transmissions by a submarine are minimised. Various periscope-mounted aerials have been developed to allow communication without surfacing.

The standard navigation system for early submarines was by eye, with use of a compass. The gyrocompass was introduced in the early part of the 20th century and inertial navigation in the 1950s. The use of satellite navigation is of limited use to submarines, except at periscope depth or when surfaced.

Military

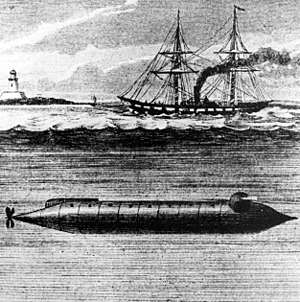

The first military submarine was Turtle in 1776. During the American Revolutionary War, Turtle (operated by Sgt. Ezra Lee, Continental Army) tried and failed to sink a British warship, HMS Eagle (flagship of the blockaders) in New York harbor on September 7, 1776. There is no record of any attack in the ships' logs.

During the War of 1812, in 1814 Silas Halsey lost his life while using a submarine in an unsuccessful attack on a British warship stationed in New London harbor.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War, the Union was the first to field a submarine. The French-designed Alligator was the first U.S. Navy sub and the first to feature compressed air (for air supply) and an air filtration system. It was the first submarine to carry a diver lock, which allowed a diver to plant electrically detonated mines on enemy ships. Initially hand-powered by oars, it was converted after 6 months to a screw propeller powered by a hand crank. With a crew of 20, it was larger than Confederate submarines. Alligator was 47 feet (14 m) long and about 4 feet (1.2 m) in diameter. It was lost in a storm off Cape Hatteras on April 1, 1863, while uncrewed and under tow to its first combat deployment at Charleston.[49]

The Intelligent Whale was built by Oliver Halstead and tested by the U.S. Navy after the American Civil War and caused the deaths of 39 men during trials.

The Confederate States of America fielded several human-powered submarines, including CSS H. L. Hunley (named for its designer and chief financier, Horace Lawson Hunley). The first Confederate submarine was the 30-foot-long (9.1 m) Pioneer, which sank a target schooner using a towed mine during tests on Lake Pontchartrain, but it was not used in combat. It was scuttled after New Orleans was captured and in 1868 was sold for scrap. The similar Bayou St. John submarine is preserved in the Louisiana State Museum. CSS Hunley was intended for attacking Union ships that were blockading Confederate seaports. The submarine had a long pole with an explosive charge in the bow, called a spar torpedo. The sub had to approach an enemy vessel, attach the explosive, move away, and then detonate it. It was extremely hazardous to operate, and had no air supply other than what was contained inside the main compartment. On two occasions, the sub sank; on the first occasion half the crew died, and on the second, the entire eight-man crew (including Hunley himself) drowned. On February 17, 1864, Hunley sank USS Housatonic off the Charleston Harbor, the first time a submarine successfully sank another ship, though it sank in the same engagement shortly after signaling its success. Submarines did not have a major impact on the outcome of the war, but did portend their coming importance to naval warfare and increased interest in their use in naval warfare.

Russo-Japanese War

On 14 June 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) placed an order for five Holland Type VII submersibles, which were built in Quincy, Massachusetts at the Fore River Yard, and shipped to Yokohama, Japan in sections. The five machines arrived on 12 December 1904.[50] Under the supervision of naval architect Arthur L. Busch, the imported Hollands were re-assembled, and the first submersibles were ready for combat operations by August 1905, but hostilities were nearing the end by that date, and no submarines saw action during the war.

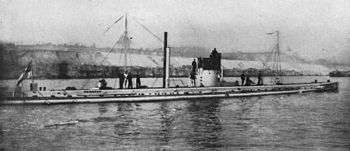

Meanwhile, the Imperial Russian Navy (IRN) purchased German constructed submersibles built by the Germaniawerft shipyards out of Kiel. In 1903 Germany successfully completed its first fully functional engine-powered submarine, Forelle (Trout),[51] It was sold to Russia in 1904 and shipped via the Trans-Siberian Railway to the combat zone during the Russo-Japanese War.[39]

Due to the naval blockade of Port Arthur, Russia sent their remaining submarines to Vladivostok, and by the end of 1904, seven subs were based there. On 1 January 1905, the IRN created the world's first operational submarine fleet around these seven submarines. The first combat patrol by the newly created IRN submarine fleet occurred on 14 February 1905, and was carried out by Delfin and Som, with each patrol normally lasting about 24 hours. Som first made contact with the enemy on 29 April, when it was fired upon by IJN torpedo boats, which withdrew shortly after opening fire and resulting in no casualties or damage to either combatant. A second contact occurred on 1 July 1905 in the Tartar Strait when two IJN torpedo boats spotted the IRN sub Keta. Unable to submerge quickly enough, Keta was unable to obtain a proper firing position, and both combatants broke contact.[52]

World War I

The first time military submarines had significant impact on a war was in World War I. Forces such as the U-boats of Germany operated against Allied commerce (Handelskrieg). The submarine's ability to function as a practical war machine relied on new tactics, their numbers, and submarine technologies such as combination diesel/electric power system that had been developed in the preceding years. More like submersible ships than the submarines of today, submarines operated primarily on the surface using standard engines, submerging occasionally to attack under battery power. They were roughly triangular in cross-section, with a distinct keel, to control rolling while surfaced, and a distinct bow.[53]

Shortly before the outbreak of World War I, submarines were employed by the Italian Regia Marina during the Italo-Turkish War without seeing any naval action, and by the Greek Navy during the Balkan Wars, where notably the French-built Delfin became the first such vessel to launch a torpedo against an enemy ship (albeit unsuccessfully).

At the start of the war, Germany had 48 submarines in service or under construction, with 29 operational. These included vessels of the diesel-engined U-19 class with the range (5,000 miles) and speed (eight knots) to operate effectively around the entire British coast.[54] Initially, Germany followed the international "Prize Rules", which required a ship's crew to be allowed to leave before sinking their ship. The U-boats saw action in the First Battle of the Atlantic.

After the British ordered transport ships to act as auxiliary cruisers, the German navy adopted unrestricted submarine warfare; generally giving no warning of an attack. During the war, 360 submarines were built, but 178 were lost. The rest were surrendered at the end of the war. A German U-boat sunk RMS Lusitania and is often cited among the reasons for the entry of the United States into the war.[55]

In August 1914, a flotilla of ten U-boats sailed from their base in Heligoland to attack Royal Navy warships in the North Sea in the first submarine war patrol in history.[56] Their aim was to sink capital ships of the British Grand Fleet, and so reduce the Grand Fleet's numerical superiority over the German High Seas Fleet. Depending more on luck than strategy, the first sortie was not a success. Only one attack was carried out, when U-15 fired a torpedo (which missed) at HMS Monarch, while two of the ten U-boats were lost. The SM U-9 had better luck. On 22 September 1914 while patrolling the Broad Fourteens, a region of the southern North Sea, U-9 found three obsolescent British Cressy-class armoured cruisers (HMS Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy), which were assigned to prevent German surface vessels from entering the eastern end of the English Channel. The U-9 fired all six of its torpedoes, reloading while submerged, and sank the three cruisers in less than an hour.

The British had 77 operational submarines at the beginning of the war, with 15 under construction. The main type was the "E class", but several experimental designs were built, including the "K class", which had a reputation for bad luck, and the "M class", which had a large deck-mounted gun. The "R class" was the first boat designed to attack other submarines. British submarines operated in the Baltic, North Sea and Atlantic, as well as in the Mediterranean and Black Sea. Over 50 were lost from various causes during the war.

France had 62 submarines at the beginning of the war, in 14 different classes. They operated mainly in the Mediterranean, and in the course of the war, 12 were lost. The Russians started the war with 58 submarines in service or under construction. The main class was the "Bars" with 24 boats. Twenty-four submarines were lost during the war.

World War II

Germany

Although Germany was banned from having submarines in the Treaty of Versailles, construction started in secret during the 1930s. When this became known, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1936 allowed Germany to achieve parity in submarines with Britain.

Germany started the war with only 65 submarines, with 21 at sea when war broke out. Germany soon built the largest submarine fleet during World War II. Due to the Treaty of Versailles limiting the surface navy, the rebuilding of the German surface forces had only begun in earnest a year before the outbreak of World War II. Having no hope of defeating the vastly superior Royal Navy decisively in a surface battle, the German High Command planned on fighting a campaign of "Guerre de course" (Merchant warfare), and immediately stopped all construction on capital surface ships, save the nearly completed Bismarck-class battleships and two cruisers, and switched the resources to submarines, which could be built more quickly. Though it took most of 1940 to expand production facilities and to start mass production, more than a thousand submarines were built by the end of the war.

Germany used submarines to devastating effect in World War II during the Battle of the Atlantic, attempting but ultimately failing to cut off Britain's supply routes by sinking more ships than Britain could replace. The supply lines were vital to Britain for food and industry, as well as armaments from Canada and the United States. Although the U-boats had been updated in the intervening years, the major innovation was improved communications, encrypted using the famous Enigma cipher machine. This allowed for mass-attack tactics or "wolfpacks" (Rudel), but was also ultimately the U-boats' downfall.

After putting to sea, the U-boats operated mostly on their own trying to find convoys in areas assigned to them by the High Command. If a convoy was found, the submarine did not attack immediately, but shadowed the convoy and radioed to the German Command to allow other submarines in the area to find the convoy. The submarines were then grouped into a larger striking force and attacked the convoy simultaneously, preferably at night while surfaced to avoid the ASDIC.

During the first few years of World War II, the Ubootwaffe ("U-boat force") scored unprecedented success with these tactics ("First Happy Time"), but were too few to have any decisive success. By the spring of 1943, German U-boat construction was at full capacity, but this was more than nullified by increased numbers of convoy escorts and aircraft, as well as technical advances like radar and sonar. High Frequency Direction Finding (HF/DF, known as Huff-Duff) and Ultra allowed the Allies to route convoys around wolfpacks when they detected radio transmissions from trailing boats. The results were devastating: from March to July of that year, over 130 U-boats were lost, 41 in May alone. Concurrent Allied losses dropped dramatically, from 750,000 tons in March to 188,000 in July. Although the Battle of the Atlantic continued to the last day of the war, the U-boat arm was unable to stem the tide of personnel and supplies, paving the way for Operation Torch, Operation Husky, and ultimately, D-Day. Winston Churchill wrote the U-boat "peril" was the only thing to ever give him cause to doubt eventual Allied victory.

By the end of the war, almost 3,000 Allied ships (175 warships, 2,825 merchantmen) were sunk by U-boats.[57] Of the 40,000 men in the U-boat service, 28,000 (70%) lost their lives.

The Germans built some novel submarine designs, including the Type XVII, which used hydrogen peroxide in a Walther turbine (named for its designer, Dr Hellmuth Walther) for propulsion. They also produced the Type XXII, which had a large battery and mechanical torpedo handling.

Italy

Italy had 116 submarines in service at the start of the war, with 24 different classes. These operated mainly in the Mediterranean theatre. Some were sent to a base at Bordeaux in Occupied France. A flotilla of several submarines also operated out of the Eritrean colonial port of Massawa.

Italian designs proved to be unsuitable for use in the Atlantic Ocean. Italian midget submarines were used in attacks against British shipping near the port of Gibraltar.

Britain

.jpg)

The Royal Navy Submarine Service had 70 operational submarines in 1939. Three classes were selected for mass production, the seagoing "S class" and the oceangoing "T class" as well as the coastal "U class". All of these classes were built in large numbers during the war.[58]

The French submarine fleet consisted of over 70 vessels (with some under construction) at the beginning of the war.[59] After the Fall of France, the French-German Armistice required the return of all French submarines to German-controlled ports in France. Some of these submarines were forcibly seized by British forces.

The main operating theatres for British submarines were off the coast of Norway, in the Mediterranean, where a flotilla of submarines successfully disrupted the Axis replenishment route to North Africa from their base in Malta, as well as in the North Sea. As Germany was a Continental power, there was little opportunity for the British to sink German shipping in this theatre of the Atlantic.

From 1940, U-class submarines were stationed at Malta, to interdict enemy supplies bound for North Africa. Over a period of three years, this force sank over 1 million tons of shipping, and fatally undermined the attempts of the German High Command to adequately support General Erwin Rommel. Rommel's Chief of Staff, Fritz Bayerlein conceded that "We would have taken Alexandria and reached the Suez Canal, if it had not been for the work of your submarines". 45 vessels were lost during this campaign, and five Victoria Crosses were awarded to submariners serving in this theatre.[60]

In addition, British submarines attacked Japanese shipping in the Far East, during the Pacific campaign.[61] The Eastern Fleet was responsible for submarine operations in the Bay of Bengal, Strait of Malacca as far as Singapore, and the western coast of Sumatra to the Equator. Few large Japanese cargo ships operated in this area, and the British submarines' main targets were small craft operating in inshore waters.[62] The submarines were deployed to conduct reconnaissance, interdict Japanese supplies travelling to Burma, and attack U-boats operating from Penang. The Eastern Fleet's submarine force continued to expand during 1944, and by October 1944 had sunk a cruiser, three submarines, six small naval vessels, 40,000 long tons (41,000 t) of merchant ships, and nearly 100 small vessels.[63] In this theatre, the only documented instance of a submarine sinking another submarine while both were submerged occurred. HMS Venturer engaged the U864 and the Venturer crew manually computed a successful firing solution against a three-dimensionally manoeveuring target using techniques which became the basis of modern torpedo computer targeting systems.

By March 1945, British boats had gained control of the Strait of Malacca, preventing any supplies from reaching the Japanese forces in Burma by sea. By this time, there were few large Japanese ships in the region, and the submarines mainly operated against small ships which they attacked with their deck guns. The submarine HMS Trenchant torpedoed and sank the heavy cruiser Ashigara in the Bangka Strait, taking down some 1,200 Japanese army troops. Three British submarines (HMS Stonehenge, Stratagem, and Porpoise) were sunk by the Japanese during the war.[64]

Japan

Japan had the most varied fleet of submarines of World War II, including manned torpedoes (Kaiten), midget submarines (Ko-hyoteki, Kairyu), medium-range submarines, purpose-built supply submarines (many for use by the Army), long-range fleet submarines (many of which carried an aircraft), submarines with the highest submerged speeds of the conflict (Sentaka I-200), and submarines that could carry multiple aircraft (WWII's largest submarine, the Sentoku I-400). These submarines were also equipped with the most advanced torpedo of the conflict, the oxygen-propelled Type 95 (what U.S. historian Samuel E. Morison postwar called "Long Lance").

Overall, despite their technical prowess, Japanese submarines, having been incorporated into the Imperial Navy's war plan of "Guerre D' Escadre" (Fleet Warfare), in contrast to Germany's war plan of "Guerre De Course", they were relatively unsuccessful. Japanese submarines were primarily used in the offensive roles against warships, which were fast, maneuverable and well-defended compared to merchant ships. In 1942, Japanese submarines sank two fleet aircraft carriers, one cruiser, and several destroyers and other warships, and damaged many others, including two battleships. They were not able to sustain these results afterward, as Allied fleets were reinforced and became better organized. By the end of the war, submarines were instead often used to transport supplies to island garrisons. During the war, Japan managed to sink about 1 million tons of merchant shipping (184 ships), compared to 1.5 million tons for Great Britain (493 ships), 4.65 million tons for the U.S. (1,079 ships) and 14.3 million tons for Germany (2,840 ships).

Early models were not very maneuverable under water, could not dive very deep, and lacked radar. Later in the war units that were fitted with radar were in some instances sunk due to the ability of U.S. radar sets to detect their emissions. For example, Batfish (SS-310) sank three such equipped submarines in the span of four days. After the war, several of Japan's most original submarines were sent to Hawaii for inspection in "Operation Road's End" (I-400, I-401, I-201 and I-203) before being scuttled by the U.S. Navy in 1946, when the Soviets demanded access to the submarines as well.

United States

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, many of the U.S. Navy's front-line Pacific Fleet surface ships were destroyed or severely damaged. The submarines survived the attack and carried the war to the enemy. Lacking support vessels, the submarines were asked to independently hunt and destroy Japanese ships and submarines. They did so very effectively.

During World War II, the submarine force was the most effective anti-ship and anti-submarine weapon in the entire American arsenal. Submarines, though only about 2 percent of the U.S. Navy, destroyed over 30 percent of the Japanese Navy, including 8 aircraft carriers, 1 battleship and 11 cruisers. U.S. submarines also destroyed over 60 percent of the Japanese merchant fleet, crippling Japan's ability to supply its military forces and industrial war effort. Allied submarines in the Pacific War destroyed more Japanese shipping than all other weapons combined. This feat was considerably aided by the Imperial Japanese Navy's failure to provide adequate escort forces for the nation's merchant fleet.

Of note, whereas Japanese submarine torpedoes of the war are considered the finest, those of U.S. Navy are considered the worst. For example, the U.S. Mark 14 torpedo typically ran ten feet too deep and was tipped with a Mk VI exploder, with both magnetic influence and contact features, neither reliable. The faulty depth control mechanism of the Mark 14 was corrected in August 1942, but field trials for the exploders were not ordered until mid-1943, when tests in Hawaii and Australia confirmed the flaws. In addition, the Mark 14 sometimes suffered circular runs, which sank at least one U.S. submarine, Tullibee.[65] Fully operational Mark 14 torpedoes were not put into service until September 1943. The Mark 15 torpedo used by U.S. surface combatants had the same Mk VI exploder and was not fixed until late 1943. One attempt to correct the problems resulted in a wakeless, electric torpedo (the Mark 18) being placed in submarine service. Tang was lost to a circular run by one of these torpedoes.[66] Given the prevalence of circular runs, there were probably other losses among boats which simply disappeared.[67]

During World War II, 314 submarines served in the United States Navy, of which nearly 260 were deployed to the Pacific.[68] On December 7, 1941, 111 boats were in commission and 203 submarines from the Gato, Balao, and Tench classes were commissioned during the war. During the war, 52 US submarines were lost to all causes, with 48 directly due to hostilities;[69] 3,505[68][70] sailors were lost, the highest percentage killed in action of any US service arm in World War II. U.S. submarines sank 1,560 enemy vessels,[68] a total tonnage of 5.3 million tons (55% of the total sunk),[71] including 8 aircraft carriers, a battleship, three heavy cruisers, and over 200 other warships, and damaged several other ships including the battleships Yamato (badly damaged by USS Skate (SS-305)) and Musashi (damaged by USS Tunny (SS-282)).[71] In addition, the Japanese merchant marine lost 16,200 sailors killed and 53,400 wounded, of some 122,000 at the start of the war, due to submarines.[71]

Post-War

During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union maintained large submarine fleets that engaged in cat-and-mouse games. This continues today, on a much-reduced scale. The Soviet Union suffered the loss of at least four submarines during this period: K-129 was lost in 1968 (which the CIA attempted to retrieve from the ocean floor with the Howard Hughes-designed ship named Glomar Explorer), K-8 in 1970, K -219 in 1986 (subject of the film Hostile Waters), and Komsomolets (the only Mike class submarine) in 1989 (which held a depth record among the military submarines—1000 m, or 1300 m according to the article K-278). Many other Soviet subs, such as K-19 (first Soviet nuclear submarine, and first Soviet sub at North Pole) were badly damaged by fire or radiation leaks. The United States lost two nuclear submarines during this time: USS Thresher and Scorpion. The Thresher was lost due to equipment failure, and the exact cause of the loss of the Scorpion is not known.

The sinking of PNS Ghazi in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was the first submarine casualty in the South Asian region.

The United Kingdom employed nuclear-powered submarines against Argentina during the 1982 Falklands War. The sinking of the cruiser ARA General Belgrano by HMS Conqueror was the first sinking by a nuclear-powered submarine in war. During this conflict, the conventional Argentinian submarine ARA Santa Fé was disabled by a Sea Skua missile, and the ARA San Luis claimed to have made unsuccessful attacks on the British fleet.

Major incidents

There have been a number of accidental sinkings, but also some collisions between submarines. Up to August 1914, there were 68 submarine accidents. There were 23 collisions, 7 battery gas explosions, 12 gasoline explosions, and 13 sinkings due to hull openings not being closed. HMS Affray was lost in the English Channel in 1951 due to the snort mast fracturing and USS Thresher in 1963 due to a pipe weld failure during a test dive. Many other scenarios have been proven to be probable causes of sinking, most notably a battery malfunction causing a torpedo to detonate internally, and the loss of the Russian Kursk on 12 August 2000 probably due to a torpedo explosion. An example of the latter was the incident between the Russian K-276 and the USS Baton Rouge in February 1992.

Since the year 2000 there have been 9 major naval incidents involving submarines. There were three Russian submarine incidents, in two of which the submarines in question were lost, along with three United States submarine incidents, one Chinese incident, one Canadian, and one Australian incident. In August 2005, AS-28, a Russian Priz-class rescue submarine, was trapped by cables and/or nets off of Petropavlovsk, and saved when a British ROV cut them free in a massive international effort.

See also

- List of submarine actions

- List of submarine museums

- List of sunken nuclear submarines

- Depth charge and Depth charge (cocktail)

- Nuclear navy

- Nuclear submarine

- Attack submarine

- List of countries with submarines

Vessels

- Nerwin (NR-1)

- Vesikko (museum submarine)

- ORP Orzeł

- Ships named Nautilus

- List of submarines of the Royal Navy

- List of submarines of the United States Navy

- List of Soviet submarines

- List of U-boats of Germany

- Kaikō ROV (deepest submarine dive)

- Bathyscaphe Trieste (deepest manned dive)

Classes

- List of submarine classes

- List of submarine classes of the Royal Navy

- List of Soviet and Russian submarine classes

- List of United States submarine classes

References

- "ABC (Madrid) - 07/03/1980, p. 89 - ABC.es Hemeroteca". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- "Love Submarines? Here's How They Were Invented". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- G. L'E. Turner, ‘Bourne, William (c.1535–1582)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. The first edition of this text is available at Wikisource: . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- Tierie, Gerrit (1932) Cornelius Drebbel (1572-1633): http://www.drebbel.net/Tierie.pdf: 63

- Tierie, Gerrit (1932) Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633): http://www.drebbel.net/Tierie.pdf: 60

- Davis, RH (1955). Deep Diving and Submarine Operations (6th ed.). Tolworth, Surbiton, Surrey: Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd. p. 693.

- Acott, C. (1999). "A brief history of diving and decompression illness". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- Tierie, Gerrit (1932) Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633): http://www.drebbel.net/Tierie.pdf: 59

- Tierie, Gerrit (1932) Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633): http://www.drebbel.net/Tierie.pdf: 62

- Tierie, Gerrit (1932) Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633): http://www.drebbel.net/Tierie.pdf: 65

- http://www.drebbel.net/1821%20Cappelle.pdf: 102

- by I.W.M.A., London, printed by M.F. for Sa: Gellibrand at the brasen Serpent in Pauls Church-yard. 1648. Quoted in Asbach-Schnitker, Brigitte: John Wilkins, Mercury ... Bibliography, 7.3 The Works of John Wilkins, n° 24

- Acott, C. (1999). "A brief history of diving and decompression illness". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- "The Invention Of The Submarine". Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- Coggins, Jack (2002). Ships and Seamen of the American Revolution. Mineola, NY: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-42072-1. OCLC 48795929.

- Compton-Hall, pp. 32–40

- "Makeshift submarine found in East River". 3 August 2007. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012.

- Egg-head skipper shore isn't upset Jotham Sederstrom and Christina Boyle, New York Daily News

- An Artist and His Sub Surrender in Brooklyn Randy Kennedy, New York Times

- Burgess, Robert Forrest (1975). Ships Beneath the Sea. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-008958-7.

-

Konstantinov, Pavel (2004). "Pervaya raketnaya podvodnaya lodka" Первая ракетная подводная лодка [THe first rocket-equipped submarine] (in Russian). Retrieved 6 May 2019.

Но еще более были потрясены случайные зеваки, обнаружив, что на берегу находился сам император Николай I в окружении немногочисленной свиты и военных и с интересом наблюдал за происходящим. Откуда было знать непосвященным чухонцам, что они явились свидетелями первых испытаний первой в мире металлической подводной лодки-ракетоносца! А управлял ею лично генерал Карл Андреевич Шильдер, создатель подводного судна.

- Hipopotamo submarine: Scale model at the Museum of Maritime History of the Ecuadorian Navy; http://www.digeim.armada.mil.ec/index.php?option=com_phocagallery&view=category&id=9:submarino-qhipopotamoq&Itemid=12 Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Elliott, David. "A short history of submarine escape: The development of an extreme air dive". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal. 29 (2). Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- James P. Delgado (2006). "Archaeological Reconnaissance of the 1865 American-Built Sub Marine Explorer at Isla San Telmo, Archipielago de las Perlas, Panama". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology Journal. 35 (2): 230–252. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2006.00100.x.

- Delgado, James P. (6 March 2012). Misadventures of a Civil War Submarine: Iron, Guns, and Pearls. Texas A&M University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-60344-472-9. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "Recovering Chile's 19th Century Shipwrecks in Valparaiso's Port". The Santiago Times. 25 November 2006. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- Pike, John. "Submarine History". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- "Torpedo History: Whitehead Torpedo Mk1". Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- "Cochran and Co 1878 - 1898". Old Merseytimes. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- "Construction and launch of the Resurgam". E. Chambré Hardman Archive. Archived from the original on 22 February 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "Submarine Heritage Centre - submarine history of Barrow-in-Furness". Submarineheritage.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- Paul Bowers (1999). The Garrett Enigma: And the Early Submarine Pioneers. Airlife. p. 167. ISBN 9781840370669.

- James P. Delgado (2011). Silent Killers: Submarines and Underwater Warfare. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781849088602. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- "French Sub Gymnote". battleships-cruisers.co.uk. Retrieved 22 August 2010.

- Humble, Richard (1981). Underwater warfare. Chartwell Books, p. 174. ISBN 978-0-89009-424-2

- "John Philip Holland - American inventor". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Galantin, Ignatius J., Admiral, USN (Ret.). Foreword to Submariner by Johnnie Coote, p.1.

- Submarines, war beneath the waves, from 1776 to the present day, by Robert Hutchinson

- Showell p. 29

- Showell p. 36

- Showell, p. 36 & 37

- "GB 106330 (A) - Improvements in or relating to Submarine or Submersible Boats". Scott's Shipbuilding & Engineering Co., and Richardson, James. May 19, 1916.

- J F Robb, Scotts of Greenock: A Family Enterprise, 1820–1920, p. 424

- Helgason, Guðmundur (2013). "HNMS O 20". uboat.net. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- Karl G. Strecker: "Vom Walter-U-Boot zum Waffelautomaten", Köster Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-89574-438-7

- List of Project 705 submarines Archived 2015-01-09 at the Wayback Machine

- "Eyes from the Deep: A History of U.S. Navy Submarine Periscopes". Undersea Warfare. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- Hill, M. N. (1962). Physical Oceanography. Allan R. Robinson. Harvard University Press. p. 498.

- Chuck Veit "The Innovative Mysterious Alligator" page 26 U.S. Naval Institute NAVAL HISTORY published August 2010 ISSN 1042-1920

- Jentschura p. 160

- Showell p. 201

- Olender p. 175

- Roger Chickering, Stig Förster, Bernd Greiner, German Historical Institute (Washington, D.C.) (2005). "A world at total war: global conflict and the politics of destruction, 1937-1945". Cambridge University Press. p.73. ISBN 978-0-521-83432-2

- Douglas Botting, pages 18-19 "The U-Boats", ISBN 978-0-7054-0630-7

- Thomas Adam. Germany and the Americas. p. 1155.

- Gibson and Prendergast, p. 2

- Crocker III, H. W. (2006). Don't Tread on Me. New York: Crown Forum. p. 310. ISBN 978-1-4000-5363-6.

- "1. Royal Navy in World War 2, Introductions". Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Paul E. Fontenoy, Submarines: An Illustrated History of Their Impact, ABC-CLIO - 2007, page 29

- ""Most Dangerous Service" A Century of Royal Navy Submarines".

- "Submarine History: Submarine Service: Operations and Support: Royal Navy". Archived from the original on 9 June 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- Mars (1971), p.216.

- McCartney (2006), pp.40–42.

- McCartney (2006), pp.42–43.

- Blair, p.576.

- Blair, pp.767-768; O'Kane, Clear the Bridge.

- Blair, passim.

- O'Kane, p. 333.

- Blair, Clay, Jr. Silent Victory, pp. 991-2. The others were lost to accidents or, in the case of Seawolf, friendly fire.

- Less the crews of S-26, R-12, and possibly Dorado lost to accident, and Seawolf, to friendly fire. S-36 and Darter, lost to grounding, took no casualties. Blair, passim.

- Blair, p.878.

Further reading

- Blair, Clay Jr., Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan, ISBN 1-55750-217-X

- Compton-Hall, Richard. Submarine Boats, the beginnings of underwater warfare, Windward, 1983.

- Fontenoy, Paul. Submarines: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO, 2007. ISBN 9781851095636

- Harris, Brayton (Captain, USN ret.). "The Navy Times Book of Submarines: A Political, Social, and Military History." Berkley Books, 1997

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Dieter Jung, Peter Mickel. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. United States Naval Institute, 1977. Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

- Lockwood, Charles A. (VAdm, USN ret.), Sink 'Em All: Submarine Warfare in the Pacific, (1951)

- Polmar, Norman & Kenneth Moore. Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U. S. and Soviet Submarines. Brassey's, Washington DC, 2004. ISBN 1574885944

- Preston, Anthony. The World's Greatest Submarines Greenwich Editions 2005.

- Showell, Jak. The U-Boat Century-German Submarine Warfare 1906–2006. Great Britain; Chatham Publishing, 2006. ISBN 1-86176-241-0.

External links

- John Holland

- German Submarines of WWII

- Submarine Simulations

- Seehund - German Midget Submarine

- Submarines of WWI

- Molch - German Midget Submarine

- Developed for the NOVA television series.

- Role of the Modern Submarine

- Submariners of WWII — World War II Submarine Veterans History Project

- German submarines using peroxide

- record breaking Japanese Submarines

- German U-Boats 1935–1945

- U.S. ship photo archive

- Israeli missile trials

- The Sub Report

- The Invention of the Submarine

- Submersibles and Technology by Graham Hawkes

- Submarine of Karl Shilder

- Royal Navy submarine history

- A century of Royal Navy submarine operations

- Royal Navy submarines

- Still floating submarine Lembit (1936)

- Submarines, the Enemy Unseen, History Today

- American Society of Safety Engineers. Journal of Professional Safety. Submarine Accidents: A 60-Year Statistical Assessment. C. Tingle. September 2009. pp. 31–39. Ordering full article: https://www.asse.org/professionalsafety/indexes/2009.php; or Reproduction less graphics/tables: http://www.allbusiness.com/government/government-bodies-offices-government/12939133-1.html.