History of Mogadishu

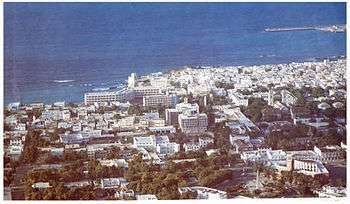

Mogadishu (Somali: Muqdisho, popularly Xamar; Arabic: مقديشو) is the largest city in Somalia and the nation's capital. Located in the coastal Benadir region on the Somali Sea, the city has served as an important port for centuries.

Antiquity

It's believed Somalis homeland is northern Somalia and they have always inhabited that territory until the Somali pastoral clans migrated to southern Somalia in the 1st century AD to populate the Horn of Africa. The Somalis then established farmlands in Jubba and Shebelle valleys and wealthy ports in southern Somali coastline and by then Mogadishu was founded.[1]

During the antiquity times. Mogadishu was part of the Somali city-states that in engaged in a lucrative trade network connecting Somali merchants with Phoenicia, Ptolemic Egypt, Greece, Parthian Persia, Saba, Nabataea and the Roman Empire. Somali sailors used the ancient Somali maritime vessel known as the beden to transport their cargo.

According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, maritime trade connected Somalis in the Mogadishu area (known to the Romans and Greeks as Sarapion) with other communities along the Indian Ocean coast as early as the 1st century CE. The ancient trading power of Sarapion has been postulated to be the predecessor of Mogadishu. Probably Sarapion was located south of actual Mogadishu, in an area where have been found Roman coins.

Medieval Period

Mogadishu Sultanate

The Sultanate of Mogadishu was established by Sultan Abubakar ibn Fakr ad-Din in the 9th century. He built the historical mosque in the year 869 C.E. in Mogadishu.[3] Ajuran (clan) was first established administration 1320 with help of khalifa Osmania. Ajuuraan Army was federation of Somali, Arabs, Turks, and others and their first capital was in Mareeg, Somalia. then Khalafe. Late century Marca lower shabelle Banadir region .[4][5]

According to Al-Yaqubi mentioned Muslims were living on the board of south Somalia. He mentioned Mogadishu in the 9th century calling it a beautiful wealthy city who are inhabited by the people of Bilad Al-Berber a medieval term used by Arabs to describe Somalis.

For many years Mogadishu functioned as the pre-eminent city in the بلد البربر (Bilad al Barbar - "Land of the Berbers"), as medieval Arabic-speakers named the Somali coast.[6][7][8][9] Following his visit to the city, the 12th-century Syrian historian Yaqut al-Hamawi (a former slave of Greek origin) wrote a global history of many places he visited Mogadishu and called it the richest and most powerful city in the region and was an Islamic center across the Indian Ocean.[10][11]

Ajuran Empire

In the early 13th century, Mogadishu along with other coastal and interior Somali cities in southern Somalia and eastern Ethiopia came under the Ajuran Sultanate control and experienced another Golden Age.

During his travels, Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi (1213–1286) noted that Mogadishu city had already become the leading Islamic center in the region.

By this time Mogadishu ruled Sultan Abubakar [12] Ibnu Faqrudin, 1269 built oldest mosque in Mogadishu till now can be viewed in Hamar weyne District. Sultan Omer ibnu Abubakar Faqrudin ruled Mogadishu (@Aroone) By the time of the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta's appearance on the Somali coast in 1331, the city was at the zenith of its prosperity. He described Mogadishu as "an exceedingly large city" with many rich merchants, which was famous for its high quality fabric that it exported to Egypt, among other places.[13][14] Battuta added that the city was ruled by a Somali Sultan, Abu Bakr ibn Sayx 'Umar,[15][16] who was originally from Berbera in northern Somalia and spoke both Somali (referred to by Battuta as Benadir, a southern Somali dialect) and Arabic with equal fluency.[16][17] The Sultan also had a retinue of wazirs (ministers), legal experts, commanders, royal eunuchs, and other officials at his beck and call.[16]

Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) noted in his book that Mogadishu was a massive metropolis city that served as the capital of the Ajuran Kingdom. He also claimed that the city of Mogadishu was a very populous city with many wealthy merchants, yet nomad in character. He referred to the characteristics of the inhabitants of Mogadishu as tall swarthy Berbers and called them the people of Al-Somaal.[18]

The ruler of the Somali Ajuran Empire sent ambassadors to China to establish diplomatic ties, creating the first ever recorded African community in China and the most notable Somali ambassador in medieval China was Sa'id of Mogadishu who was the first African man to set foot in China. In return, Emperor Yongle, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), dispatched one of the largest fleets in history to trade with the Somali nation. The fleet, under the leadership of the famed Hui Muslim Zheng He, arrived at[Mogadishu the capital of Ajuran Empire while the city was at its zenith. Along with gold, frankincense and fabrics, Zheng brought back the first ever African wildlife to China, which included hippos, giraffes and gazelles.[19][20][21][22]

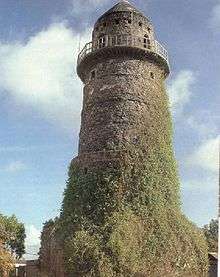

Vasco Da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[23] In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[24] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria),[25] together with Merca and Barawa also served as transit stops for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[26] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz also brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[27]

The Portuguese Empire was unsuccessful of conquering Mogadishu where the powerful naval Portuguese commander called João de Sepúvelda and his army fleets was soundly defeated by the powerful Ajuran navy during the Battle of Benadir.[28]

According to the 16th-century explorer, Leo Africanus indicates that the native inhabitants of the Mogadishu the capital of Ajuran Sultanate polity were of the same origins as the denizens of the northern people of Zeila the capital of Adal Sultanate. They were generally tall with an olive skin complexion, with some being darker and spoke Somali. They would wear traditional rich white silk wrapped around their bodies and have Islamic turbans and coastal people would only wear sarongs, and use Arabic writing script as their lingua franca. Their weaponry consisted of traditional Somali weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, battle axe, and bows, although they received assistance from its close ally the Ottoman Empire and with the import of firearms such as muskets and cannons. Most were Muslims, although a few adhered to heathen bedouin tradition; there were also a number of Abyssinian Christians further inland. Mogadishu itself was a wealthy, powerful and well-built city-state, which maintained commercial trade with kingdoms across the world. The metropolis city was surrounded by walled stone fortifications.[29][30]

After enterin Mogadishu, the Darandoolle quarrelled with the Ajuran, over watering rights. The Ajuran had decreed: ‘At the wells in our territory, the people known as Darandoolle and the other Hiraab cannot water their herds by day, but only at night’’…Then all the Darandoolle gathered in one place. The leaders decided to make war on the Ajuran. They found the King of the Ajuran in a huge palace in Mogadishu where he was seated on the rock. They killed him with a sword. As they struck him with the sword, they split his body together with the rock on which he was seated. He died immediately and the Ajuran migrated out of the country.’

The Darandoolle became as such the first group to rebel against the tyranny of Ajuran in the interior, and ever since this Ajuran defeat, other groups would follow in the rebellion which would eventually bring down Ajuran rule of the inter-riverine region.

After the defeat of the Ajuran in the interior, the Darandoolle Mudulood established themselves around Mogadishu and Shabelle river valley, in which Wacdaan inhabited the environs of Afgoye, Hilibi in Lower Shabelle, Moobleen went part of the region now known as Middle Shabelle, while the Mataan established themselves in and around Mogadishu city, where 1720 Mataan collected tax and port tariffs of the city and emerged as the authority of Mogadishu city.[31][32]

Early Modern Period

Geledi Sultanate

In the late 1800s, the Omani Sultan of Zanzibar also briefly claimed to control Mogadishu in the Horn and southern Somalia. However, power on the ground remained in the hands of the powerful Somali kingdom called Geledi Sultanate (which, also holding sway over the Jubba River and Shebelle region in Somalia's interior, was at its zenith).[33] In 1892, Geledi ruler: Osman Ahmed leased the city to Italy. The Italians eventually purchased the executive rights in 1905, and made Mogadishu the capital of the newly established Italian Somaliland.[34]

Italian Somalia

In 1892, Osman Ahmed leased the city to Italy. Italy purchased the city in 1905 and made Mogadishu the capital of the newly established Italian Somaliland.[35]

In the early 1930s, the new Italian governors, Guido Corni and Maurizio Rava, started a policy of non-coercive assimilation of locals. Many Mogadishu residents were subsequently enlisted into the Italian colonial troops, and thousands of Italian settlers moved to live in the city. Mogadishu also re-assumed its historic position as an important commercial centre, with some small manufacturing companies established within the city limits and in some agricultural areas around the capital, such as Genale and Jowhar (Villaggio duca degli Abruzzi).[36]

Mogadishu underwent a period of infrastructural expansion in the late 1930s, with new buildings and avenues such as the "Arch of Triumph" erected in 1934. In 1936, the city had a population of 50,000 inhabitants of which 20,000 were Italian Somalis.[37] The Italian settlers also connected the city to Jowhar with a 114 km railway and a newly asphalted Imperial Road leading toward to Addis Ababa. In the late 1930s was created the international airport Petrella with a huge enlargement of the port of Mogadishu.

In 1941, British forces invaded and occupied Mogadishu and Italian Somaliland at large as part of the East African Campaign of World War II.

Somali Youth League

The Somali Youth League formed in 1943 succeeded in uniting all Somali clans under its flag and led the country on the road to independence by drawing inspiration from the early 20th century Somali nationalist; Mohammed Abdullah Hassan and his Dervish Dream, as well as invoking the history of the medieval Somali empires and Kingdoms. SYL called for national unity and rejected clan divisions. Faced with growing Italian political pressure inimical to continued British tenure and to Somali aspirations for independence, the Somalis and the British came to see each other as allies. The situation prompted British officials to encourage the Somalis to form political parties. In 1945, the Potsdam conference was held, where it was decided not to return Italian Somaliland to Italy.[38]

Somali nationalist agitation against the possibility of Italian rule reached the level of violent confrontation in 1948, when on 11 January, large riots broke out that left fifty-two Italians (and 14 Somalis pro-Italy) dead in the streets of Mogadishu and other coastal cities in which many more were injured. In Mogadishu, a two-hour battle "with bullets, arrows, broken bottles and knives" ensued during an SYL parade. During those clashes Hawo Tako participated, following the visit of the Four-Power Commission, where she eventually was killed.[39] She later became a symbol for Pan-Somalism, and the nationalist Somali Youth League (SYL), who proclaimed her a martyr. When in 1949 news reached Mogadishu that the UN General Assembly was discussing the possibility of the return of Italian administration, more violent riots broke out in the city. In November 1949, the United Nations opted to grant Italy trusteeship of Italian Somaliland, but only under close supervision and on the condition — first proposed by the SYL and other nascent Somali political organizations that were then agitating for independence — that Somalia should achieve independence within ten years.[40][41]

Trust Territory of Somalia (1950-1960)

Following the dissolution of the former Italian Somaliland, the new Trust Territory of Somalia was established as a transitional step toward eventual independence. Italy would administer the polity from 1950 to 1960 under a UN mandate.[42]

This period was marked by significant urban and economic development.[42] New post-secondary institutions of law, economics and social studies were also founded. These academies were affiliated with the University of Rome and included the Somali National University.

On 13 April 1956, administration of the territory was transferred in full to the Somali politicians, and a seventy-member legislative assembly was formed with the participation of SYL members (who agreed with the Italians). The first general elections in Somalia under universal suffrage were won by the SYL, whose then-leader, Abdullahi Issa, became prime minister, and Aden Abdulle Osman Daar became speaker of parliament. The new government would go on to implement various economic and social reforms.

British Somaliland became independent on June 26, 1960 as the State of Somaliland, and the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somaliland) followed suit five days later.[43] On July 1, 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic, with Mogadishu as the nation's capital.[44][45]

Independence

A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa and other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf as President of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President of the Somali Republic and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister (later to become President from 1967–1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum, the people of Somalia ratified a new constitution, which was first drafted in 1960.[46] In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke.

In the first national elections after independence, held in Mogadishu on 30 March 1964, the SYL won an absolute majority of 69 of the 123 parliamentary seats. The remaining seats were divided among 11 parties. Five years from then, in general elections held in March 1969, the ruling SYL returned to power. However, on 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[47]

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Kediye officially held the title of "Father of the Revolution," and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[48] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[49][50] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[51]

The revolutionary army established various large-scale public works programs, including the Mogadishu Stadium. In addition to a nationalization program of industry and land, the Mogadishu-based new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League (AL) in 1974.[52]

After fallout from the unsuccessful Ogaden campaign of the late 1970s, the Barre administration began arresting government and military officials under suspicion of participation in the abortive 1978 coup d'état.[53][54] Most of the people who had allegedly helped plot the putsch were summarily executed.[55] However, several officials managed to escape abroad and started to form the first of various dissident groups dedicated to ousting Barre's regime by force.[56]

Somali Civil War

Collapse of government and UN intervention

By the late 1980s, the moral authority of Barre's regime had collapsed. The authorities became increasingly totalitarian, and resistance movements, encouraged by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration, sprang up across the country. This eventually led in 1991 to the outbreak of the civil war, the toppling of Barre's government, and the disbandment of the Somali National Army (SNA). Many of the opposition groups subsequently began competing for influence in the power vacuum that followed the ouster of Barre's regime. Armed factions led by USC commanders General Mohamed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, in particular, clashed as each sought to exert authority over the capital.[57]

UN Security Council Resolution 733 and UN Security Council Resolution 746 led to the creation of UNOSOM I, the first stabilization mission in Somalia after the dissolution of the central government. United Nations Security Council Resolution 794 was unanimously passed on December 3, 1992, which approved a coalition of United Nations peacekeepers led by the United States. Forming the Unified Task Force (UNITAF), the alliance was tasked with assuring security until humanitarian efforts were transferred to the UN. Landing in 1993, the UN peacekeeping coalition started the two-year United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) primarily in the south.[58]

Some of the militias that were then competing for power interpreted the UN troops' presence as a threat to their hegemony. Consequently, several gun battles took place in Mogadishu between local gunmen and peacekeepers. Among these was the Battle of Mogadishu of 1993, an unsuccessful attempt by US troops to apprehend faction leader Aidid.

With these casualties, United States President Bill Clinton withdrew American forces in 1994. Two factions in Mogadishu reached a peace accord the same year, on January 16. However, fighting continued for control over the city, prompting the eventual withdrawal of the last international peacekeepers by March 3, 1995.

General Aidid later declared himself president in June 1995. By 1996, his forces had captured strategic neighborhoods in Mogadishu and some outlying territory. Following renewed fighting in the city and Hoddur, Aidid ultimately died in July 1996 from gunshot wounds suffered in a street battle.

Second Battle of Mogadishu

On 7 May 2006, fighting broke out between Islamist militias and an alliance of Somali faction leaders over control of Mogadishu. The opposing forces were the Alliance for the Restoration of Peace and Counter-Terrorism (ARPCT), and militia loyal to the Islamic Court Union (ICU). The conflict began in mid-February 2006 when various warlords formed the ARPCT to challenge the emerging influence of the ICU. It was alleged that the United States had been provided funding for the ARPCT due to concerns that the ICU had ties to al-Qaeda.[59] Most of the combat was concentrated in the Sii-Sii (often written "CC" in English) district in northern Mogadishu with both the Islamist militias and the secular factions leaders fighting for control of Mogadishu. On 5 June 2006, the ICU militia seized the city.

Fall of Mogadishu

While the ICU consolidated control over Mogadishu, a UN-supported Transitional Government remained undefeated in Baidoa, despite a series of military setbacks. An attempt by the ICU to capture Baidoa prompted a military intervention by Ethiopia in support of the Transitional Government starting December 21, 2006. On December 25 Ethiopian jets bombed Mogadishu's main airport held by the ICU since June. Witnesses reported MiG fighter jets fired missiles into the airport twice. One person was killed and a number injured. Further north, Beledweyne was also bombed, according to witnesses.[60] The fighting between the Ethiopian-backed TFG and the ICU became stretched to over 400 km (250 mi) of land.[61]

Following a rapid advance, Ethiopian and pro-government militias surrounded Mogadishu. A spokesman stated that the troops would besiege the city but not attack it in order to avoid civilian casualties.[62] On December 27, reports stated that the ICU was abandoning the city. On December 28, 2006, pro-government militias claimed to have taken control of key locations, including the former presidential palace.[63]

Battle of Mogadishu (2007)

In January 2007, an Islamic insurgency erupted in Mogadishu, targeting government and Ethiopian forces. A helicopter was shot down as battles engulf in the city on March 30, 2007. Two Ethiopian helicopters fired on a rebel stronghold before one was hit by a missile. In addition, Ethiopia told its forces had killed 200 insurgents in a two-day joint offensive with Somali troops against the Islamic Courts Union.[64]

Al-Shabaab insurgency

Following its defeat in the Battle of Ras Kamboni, the Islamic Courts Union splintered into several different factions. Some of the more radical elements, including Al-Shabaab, regrouped to continue their insurgency against the TFG and oppose the Ethiopian military's presence in Somalia. Throughout 2007 and 2008, Al-Shabaab scored military victories, seizing control of key towns and ports in both central and southern Somalia. At the end of 2008, the group had captured Baidoa but not Mogadishu. By January 2009, Al-Shabaab and other militias had managed to force the Ethiopian troops to retreat, leaving behind an under-equipped African Union peacekeeping force to assist the Transitional Federal Government's troops.[65]

Between May 31 and June 9, 2008, representatives of Somalia's federal government and the moderate Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS) group of Islamist rebels participated in peace talks in Djibouti brokered by the UN. The conference ended with a signed agreement calling for the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops in exchange for the cessation of armed confrontation. Parliament was subsequently expanded to 550 seats to accommodate ARS members, which then elected a new president.[66] With the help of a small team of African Union troops, the coalition government also began a counteroffensive in February 2009 to retake control of the southern half of the country. To solidify its control of southern Somalia, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union, other members of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, and Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufi militia.[67]

Urban renewal

In November 2010, a new technocratic government was elected to office, which enacted numerous reforms, especially in the security sector.[68] By August 2011, the new administration and its AMISOM allies had managed to capture all of Mogadishu from the Al-Shabaab militants.[69] Mogadishu has subsequently experienced a period of intense reconstruction and urban renewal spearheaded by the Somali diaspora, the municipal authorities and Turkey, a historic ally of Somalia.[70][71]

References

- Abdullahi, Abdurahman (18 September 2017). Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1. Adonis and Abbey Publishers. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-909112-79-7.

- http://phonebookoftheworld.com/mogadishu/

- Oadeye. "Sultanate of Mogadishu (10th -16th century): spotlight on Middle Ages African global trade hub". Think Africa. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- I.M. Lewis, Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar, and Saho, Issue 1, (International African Institute: 1955), p. 47.

- I.M. Lewis, The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1965), p. 37

- M. Elfasi, Ivan Hrbek "Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century", "General History of Africa". Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama, (Cambridge University Press: 1998), p. 121.

- J. D. Fage, Roland Oliver, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa, (Cambridge University Press: 1977), p. 190.

- George Wynn Brereton Huntingford, Agatharchides, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs "On the Erythraean Sea", (Hakluyt Society: 1980), p. 83.

- Roland Anthony Oliver, J. D. Fage, Journal of African history, Volume 7, (Cambridge University Press.: 1966), p. 30.

- I.M. Lewis, A modern history of Somalia: nation and state in the Horn of Africa, 2nd edition, revised, illustrated, (Westview Press: 1988), p. 20.

- Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. US: ABC-CLIO. p. 252.

- Helen Chapin Metz (1992). Somalia: A Country Study. US: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844407755.

- P. L. Shinnie, The African Iron Age, (Clarendon Press: 1971), p.135

- Versteegh, Kees (2008). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, Volume 4. Brill. p. 276. ISBN 9004144765.

- David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State, (Westview Press: 1987), p. 15.

- Chapurukha Makokha Kusimba, The Rise and Fall of Swahili States, (AltaMira Press: 1999), p.58

- Brett, Michael (1 January 1999). "Ibn Khaldun and the Medieval Maghrib". Ashgate/Variorum. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", Natural History Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rice, Xan (25 July 2010). "Chinese archaeologists' African quest for sunken ship of Ming admiral". The Guardian.

- "Could a rusty coin re-write Chinese-African history?". BBC News. 18 October 2010.

- "Zheng He'S Voyages to the Western Oceans 郑和下西洋". People.chinese.cn. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Da Gama's First Voyage pg.88

- East Africa and its Invaders pg.38

- Alpers, Edward A. (1976). "Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa, c. 1500-1800". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 9 (1): 35. doi:10.2307/217389. JSTOR 217389.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Nigel (2003). The Return of Cosmopolitan Capital: Globalization, the State and War. I.B.Tauris. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86064-786-4.

- Barendse, Rene J. (2002). The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-45835-7.

- The Portuguese period in East Africa – p. 112

- (Africanus), Leo (6 April 1969). "A Geographical Historie of Africa". Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- Dunn, Ross E. (1987). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta. Berkeley: University of California. p. 373. ISBN 0-520-05771-6., p. 125

- Enrico, Cerulli, How a Hawiye tribe used to live, Chapter 4, scritti vari editi ed inediti, Vol. 2, edited by Enrico Cerulli, Roma

- Lee V. Cassanelli, Towns and Trading centres in Somalia: A Nomadic perspective, Philadelphia, 1980, pp. 8–9.

- Lewis, I. M. (1988). A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa. Westview Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-8133-7402-4.

- Hamilton, Janice (1 January 2007). Somalia in Pictures. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8225-6586-4.

- https://dadfeatured.blogspot.com/2018/05/italian-mogadishu.html Italian Mogadiscio]

- Bevilacqua, Piero. Storia dell'emigrazione italiana. p. 233

- Italian architecture in Somalia (in Italian)

- Federal Research Division, Somalia: A Country Study, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p. 38.

- Castagno, p. 73.

- Aristide R. Zolberg et al., Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World, (Oxford University Press: 1992), p. 106.

- Henry Louis Gates, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p. 1749.

- Trusteeship and Protectorate: The Road to Independence of Somalia

- Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p. 835

- Somalia

- Encyclopædia Britannica, The New Encyclopædia Britannica, (Encyclopædia Britannica: 2002), p. 835.

- Greystone Press Staff, The Illustrated Library of The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East, (Greystone Press: 1967), p. 338

- Moshe Y. Sachs, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Volume 2, (Worldmark Press: 1988), p. 290.

- Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Richard Ford (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56902-073-6.

- J. D. Fage, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge history of Africa, Volume 8, (Cambridge University Press: 1985), p. 478.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac, Volume 25, (Grolier: 1995), p. 214.

- Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy, (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p. 279 ISBN 0-7099-2709-6.

- Benjamin Frankel, The Cold War, 1945–1991: Leaders and other important figures in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, and the Third World, (Gale Research: 1992), p. 306.

- ARR: Arab report and record, (Economic Features, ltd.: 1978), p. 602.

- Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part I" (PDF). WardheerNews. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 3, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- New People Media Centre, New people, Issues 94–105, (New People Media Centre: Comboni Missionaries, 2005).

- Nina J. Fitzgerald, Somalia: issues, history, and bibliography, (Nova Publishers: 2002), p. 25.

- Library Information and Research Service, The Middle East: Abstracts and index, Volume 2, (Library Information and Research Service: 1999), p. 327.

- Ken Rutherford, Humanitarianism Under Fire: The US and UN Intervention in Somalia, Kumarian Press, July 2008 ISBN 1-56549-260-9

- "US cash support for Somali warlords 'destabilising nation'". New Zealand Herald, Reuters, The Independent. June 7, 2006. Retrieved 2007-01-08.

- Ethiopia jets bomb Somalia airport CNN

- Ethiopia attacks Somalia airport BBC

- Pro-govt troops to besiege Mogadishu: Somali envoy Archived 2007-02-16 at the Wayback Machine Reuters

- Somali govt close to taking Mogadishu Archived 2006-12-17 at the Wayback Machine Reuters

- Helicopter shot down as battles engulf Mogadishu Reuters

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2009-05-01). "USCIRF Annual Report 2009 – The Commission's Watch List: Somalia". Unhcr.org. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2010-06-27.

- "Somalia". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009-05-14. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- kamaal says: (2010-05-22). "UN boss urges support for Somalia ahead of Istanbul summit". Horseedmedia.net. Archived from the original on 2010-06-19. Retrieved 2010-06-27.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- "Security Council Meeting on Somalia". Somaliweyn.org. Archived from the original on 2014-01-05.

- Independent Newspapers Online (2011-08-10). "Al-Shabaab 'dug in like rats'". Iol.co.za.

- Guled, Abdi (3 April 2012). "Sports, arts and streetlights: Semblance of normal life returns to Mogadishu, despite mortars". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 15 January 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- Mulupi, Dinfin. "Mogadishu: East Africa's newest business destination?". Retrieved 26 June 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Mogadishu. |