Sultanate of Mogadishu

The Sultanate of Mogadishu (Somali: Saldanadda Muqdisho, Arabic: سلطنة مقديشو) (fl. 9th-13th centuries[1]), also known as the Kingdom of Magadazo,[1] was a medieval Somali trading empire centered in southern Somalia. It rose as one of the preeminent powers in the Horn of Africa during the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries. Subsequently, it served as the capital for the Ajuran Empire during the early 13th century. The Mogadishu Sultanate maintained a vast trading network, dominated the regional gold trade, minted its own currency, and left an extensive architectural legacy in present-day southern Somalia.[2]

Sultanate of Mogadishu Saldanadda Muqdisho سلطنة مقديشو | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9th century–13th century | |||||||

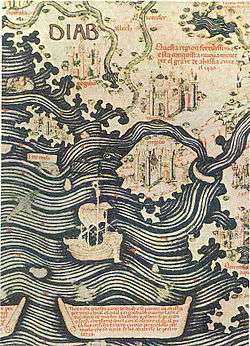

The "City of Mogadishu" on Fra Mauro's medieval map. | |||||||

| Capital | Mogadishu | ||||||

| Common languages | Somali, Arabic | ||||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||

| Sultan | |||||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||||

• 9th century | 9th century | ||||||

• 10th century[1] | 13th century | ||||||

| Currency | Mogadishan | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | |||||||

History

According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, maritime trade connected Somalis in the Mogadishu vicinity with other communities along the Indian Ocean coast as early as the 1st century CE. The ancient trading power of Sarapion has been postulated to be the predecessor of Mogadishu. During the 8th century, Mogadishu was well-suited to become a regional center for commerce.

The sultanate of Mogadishu and the Caliphates

In the year 700 Abdulmalik ibn marwan sends an expedition to conquer Mogadishu and secure its kharaj or annual tribute.[3] According to the kitab al zunuj abdulmalik ibn marwan dispatched an expedition under the command of Musa ibn umar al khathami to Mogadishu and Kilwa.[4]

the directives given to musa ibn umar were identical of those given to any other muslim conqueror, those directives were to secure the taxation of al kharaj, to teach the quran and to safeguard the security of the country and assure its loyalty to the Ummayad caliphate.[5] However al kathami would report to the caliph that the muslims in these cities had already converted during the time of caliph umar ibn khitab and still honor their allegiance to the caliph.[6]

Yahya ibn umar the messenger to the abbasid caliph Abu Jafar al Mansur reported that the sultan of Mogadishu and the people of his country were "on their oath to the caliphate and paid taxes regularly".[7]

In the year 804 Mogadishu rebelled against the Abbasid caliph Harun al rashid who sent a punitive expeditions against them.[8][9] However he was unable to quell the rebellion of the Sultan of mogadishu as the rebellions continued.[10]

Sultanate of Mogadishu period

The origins of the name Mogadishu (Muqdisho) has many theories but it is most likely derived from a morphology of the Arabic Language "Maqa'id Shah", meaning "Seat of the Shah" in Arabic, Shah is the Persian word for King.[11] This theory is backed with the evident presence of Persian and Arab influence in establishing the city. Another theory suggests that the name Mogadishu is derived from the Swahili term "Mwiji wa Mwisho" meaning the last city. This theory is strongly supported due to Mogadishu in fact being a part of the Swahili Coast cities.[12]

The Sultanate of Mogadishu was established by a local Somali man called Fakr ad-Din who hails from the Ajuran (clan) and was the first Sultan of Mogadishu Sultanate and founder of Garen Dynasty.[13][14]

According to Al-Yaqubi mentioned Muslims were living on the board of southern Somalia. He mentioned Mogadishu in the 9th century calling it a beautiful wealthy city who are inhabited by the people of Bilad Al-Berber, a medieval term used by Arabs to describe Somalis.[15]

For many years Mogadishu functioned as the pre-eminent city in the بلد البربر (Bilad al Barbar - "Land of the Berbers"), as medieval Arabic-speakers named the Somali coast.[16][17][18][19] Following his visit to the city, the 12th-century Syrian historian Yaqut al-Hamawi (a former slave of Greek origin) wrote a global history of many places he visited Mogadishu and called it the richest and most powerful city in the region and was an Islamic center across the Indian Ocean.[20][21]

Archaeological excavations have recovered many coins from China, Sri Lanka, and Vietnam. The majority of the Chinese coins date to the Song Dynasty, although the Ming Dynasty and Qing Dynasty "are also represented,"[22] according to Richard Pankhurst.

Ajuran Empire period

In the early 13th century, Mogadishu along with other coastal and interior Somali cities in southern Somalia and eastern Ethiopia came under the Ajuran Sultanate control and experienced another Golden Age.

During his travels, Ibn Sa'id al-Maghribi (1213–1286) noted that Mogadishu city had already become the leading Islamic center in the region.[23] By the time of the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta's appearance on the Somali coast in 1331, the city was at the zenith of its prosperity. He described Mogadishu as "an exceedingly large city" with many rich merchants, which was famous for its high quality fabric that it exported to Egypt, among other places.[24][25] Battuta added that the city was ruled by a Somali Sultan, Abu Bakr ibn Sayx 'Umar,[26][27] who was originally from Berbera in northern Somalia and spoke both Somali (referred to by Battuta as Benadir, a southern Somali dialect) and Arabic with equal fluency.[27][28] The Sultan also had a retinue of wazirs (ministers), legal experts, commanders, royal eunuchs, and other officials at his beck and call.[27]

Ibn Khaldun (1332 to 1406) noted in his book that Mogadishu was a massive metropolis city that served as the capital of the Ajuran Kingdom. He also claimed that the city of Mogadishu was a very populous city with many wealthy merchants, yet nomad in character. He referred to the characteristics of the inhabitants of Mogadishu as tall swarthy Berbers and called them the people of Al-Somaal.[29]

The ruler of the Somali Ajuran Empire sent ambassadors to China to establish diplomatic ties, creating the first ever recorded African community in China and the most notable Somali ambassador in medieval China was Sa'id of Mogadishu who was the first African man to set foot in China. In return, Emperor Yongle, the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), dispatched one of the largest fleets in history to trade with the Somali nation. The fleet, under the leadership of the famed Hui Muslim Zheng He, arrived at[Mogadishu the capital of Ajuran Empire while the city was at its zenith. Along with gold, frankincense and fabrics, Zheng brought back the first ever African wildlife to China, which included hippos, giraffes and gazelles.[30][31][32][33]

Vasco Da Gama, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its centre and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[34] In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya sailed to Mogadishu with cloths and spices for which they in return received gold, wax and ivory. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat, wheat, barley, horses, and fruit on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants.[35] Mogadishu, the center of a thriving weaving industry known as toob benadir (specialized for the markets in Egypt and Syria),[36] together with Merca and Barawa also served as transit stops for Swahili merchants from Mombasa and Malindi and for the gold trade from Kilwa.[37] Jewish merchants from the Hormuz also brought their Indian textile and fruit to the Somali coast in exchange for grain and wood.[38]

The Portuguese Empire was unsuccessful of conquering Mogadishu where the powerful naval Portuguese commander called João de Sepúvelda and his army fleets was soundly defeated by the powerful Ajuran navy during the Battle of Benadir.[39]

According to the 16th-century explorer, Leo Africanus indicates that the native inhabitants of the Mogadishu the capital of Ajuran Sultanate polity were of the same origins as the citizens of the northern people of Zeila the capital of Adal Sultanate. They were generally tall with an brown skin complexion, with some being darker and spoke Somali. They would wear traditional rich white silk wrapped around their bodies and have Islamic turbans and coastal people would only wear sarongs, and use Arabic writing script as their lingua franca. Their weaponry consisted of traditional Somali weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, battle axe, and bows, although they received assistance from its close ally the Ottoman Empire and with the import of firearms such as muskets and cannons. Most were Muslims, although a few adhered to heathen bedouin tradition; there were also a number of Abyssinian Christians further inland. Mogadishu itself was a wealthy, powerful and well-built city-state, which maintained commercial trade with kingdoms across the world. The metropolis city was surrounded by walled stone fortifications.[40][41]

Trade

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Somalia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Somali merchants from Mogadishu established a colony in Mozambique to extract gold from the mines in Sofala.[42]

During the 9th century, Mogadishu minted its own Mogadishu currency for its medieval trading empire in the Indian Ocean.[43][44] It centralized its commercial hegemony by minting coins to facilitate regional trade. The currency bore the names of the 13 successive Sultans of Mogadishu. The oldest pieces date back to 923-24 and on the front bear the name of Imsail ibn Muhahamad, the then Sultan of Mogadishu.[45] On the back of the coins, the names of the four Caliphs of the Rashidun Caliphate are inscribed.[46] Other coins were also minted in the style of the extant Fatimid and the Ottoman currencies. Mogadishan coins were in widespread circulation. Pieces have been found as far away as modern United Arab Emirates, where a coin bearing the name of a 12th-century Somali Sultan Ali b. Yusuf of Mogadishu was excavated.[43] Bronze pieces belonging to the Sultans of Mogadishu have also been found at Belid near Salalah in Dhofar.[47]

Upon arrival in Mogadishu's harbour, it was custom for small boats to approach the arriving vessel, and their occupants to offer food and hospitality to the merchants on the ship. If a merchant accepted such an offer, then he was obligated to lodge in that person's house and to accept their services as sales agent for whatever business they transacted in Mogadishu.

Sultans of Mogadishu

The various Sultans of Mogadishu are mainly known from the Mogadishan currency on which many of their names are engraved. However, their succession dates and genealogical relations are obscure.[48] The founder of the Sultanate was reportedly Fakr ad-Din, who hails from the Ajuran (clan) and was the first Sultan of Mogadishu Sultanate and founder of Garen Dynasty.[49] While only a handful of the pieces have been precisely dated, the Mogadishu Sultanate's first coins were minted at the beginning of the 9th century, with the last issued around the early 13th century. For trade, the Ajuran Sultanate minted its own Ajuran currency.[50] It also utilized the Mogadishan currency originally minted by the Sultanate of Mogadishu, which later became incorporated into the Ajuran Empire during the 13th century.[44] Mogadishan coins have been found as far away as the present-day country of the United Arab Emirates in the Middle East.[51] The following list of the Sultans of Mogadishu is abridged and is primarily derived from these mints.[52] The first of two dates uses the Islamic calendar, with the second using the Julian calendar; single dates are based on the Julian (European) calendar.

| # | Sultan | Reign | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Abu Bakr b. Fakhr ad Din | fl 850 | Founder of the Mogadishu Sultanate's first ruling house, the Garen dynasty. |

| 2 | Ismail b. Muhammad | fl 1134 | Golden age for Mogadishu Sultanate |

| 3 | Al-Rahman b. al-Musa'id | probably 8th/14th century | |

| 4 | Yusuf b. Sa'id | fl 9th/13th century | |

| 5 | Sultan Muhammad | fl 9th/13th century | |

| 6 | Rasul b. 'Ali | fl 9th/13th century | |

| 7 | Yusuf b. Abi Bakr | fl 9th/13th century | |

| 8 | Malik b. Sa'id | unknown dates, style of 1th/13th century | |

| 9 | Sultan 'Umar | fl 9th/13th century (?) | |

| 10 | Zubayr b. 'Umar | fl c. 9th/13th century |

References

- Africanus, Leo (1526). The History and Description of Africa. Hakluyt Society. p. 53.

Adea, the second kingdome of the land of Aian, situate upon the easterne Ocean, is confined northward by the kingdome of Adel, & westward by the Abassin empire[...] unto the foresaid kingdome of Adea belongeth the kingdome of Magadazo, so called of the principall citie therein

- Jenkins, Everett (1 July 2000). The Muslim Diaspora (Volume 2, 1500-1799): A Comprehensive Chronolog. Mcfarland. p. 49. Retrieved 22 January 2017.

Mogadishu history.

- Haji Mukhtar, Mohamed. al rashid mogadishu&f=false Historical Dictionary of Somalia Check

|url=value (help). - Abdullahi, Abdurahman. al rashid mogadishu&f=false Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1 By Abdullahi, Abdurahman Check

|url=value (help). - Zeynab, Ali. malik ibn marwan somalia&f=false Cataclysm:: Secrets of the Horn of Africa Check

|url=value (help). - Abdullahi, Abdurahman. al rashid mogadishu&f=false Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1 By Abdullahi, Abdurahman Check

|url=value (help). - Abdullahi, Abdurahman. al rashid mogadishu&f=false Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1 By Abdullahi, Abdurahman Check

|url=value (help). - Abdullahi, Abdurahman. al rashid mogadishu&f=false Making Sense of Somali History: Volume 1 By Abdullahi, Abdurahman Check

|url=value (help). - Haji Mukhtar, Mohamed. al rashid mogadishu&f=false Historical Dictionary of Somalia Check

|url=value (help). - Jimale Ahmed, Ali. al rashid mogadishu&f=false The Invention of Somalia Check

|url=value (help). - Metz, H., 1993. Somalia: A Country Study. Washington: Federal Research Division - Library of Congress, p.8.

- Unruh, J., 2018. (PDF) Mogadishu City. [online] ResearchGate. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327041276_Mogadishu_City> [Accessed 28 April 2020].

- I.M. Lewis, Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar, and Saho, Issue 1, (International African Institute: 1955), p. 47.

- I.M. Lewis, The modern history of Somaliland: from nation to state, (Weidenfeld & Nicolson: 1965), p. 37

- https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Q2GkZwEACAAJ&dq=al+yaqubi&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjGldyXvKDaAhWHL8AKHeBBApEQ6AEILzAB

- M. Elfasi, Ivan Hrbek "Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century", "General History of Africa". Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama, (Cambridge University Press: 1998), p. 121.

- J. D. Fage, Roland Oliver, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa, (Cambridge University Press: 1977), p. 190.

- George Wynn Brereton Huntingford, Agatharchides, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs "On the Erythraean Sea", (Hakluyt Society: 1980), p. 83.

- Roland Anthony Oliver, J. D. Fage, Journal of African history, Volume 7, (Cambridge University Press.: 1966), p. 30.

- I.M. Lewis, A modern history of Somalia: nation and state in the Horn of Africa, 2nd edition, revised, illustrated, (Westview Press: 1988), p. 20.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1961). An Introduction to the Economic History of Ethiopia. London: Lalibela House. ASIN B000J1GFHC., p. 268

- Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (2007). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. US: ABC-CLIO. p. 252.

- Helen Chapin Metz (1992). Somalia: A Country Study. US: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 0844407755.

- P. L. Shinnie, The African Iron Age, (Clarendon Press: 1971), p.135

- Versteegh, Kees (2008). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, Volume 4. Brill. p. 276. ISBN 9004144765.

- David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State, (Westview Press: 1987), p. 15.

- Chapurukha Makokha Kusimba, The Rise and Fall of Swahili States, (AltaMira Press: 1999), p.58

- Brett, Michael (1 January 1999). "Ibn Khaldun and the Medieval Maghrib". Ashgate/Variorum. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", Natural History Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rice, Xan (25 July 2010). "Chinese archaeologists' African quest for sunken ship of Ming admiral". The Guardian.

- "Could a rusty coin re-write Chinese-African history?". BBC News. 18 October 2010.

- "Zheng He'S Voyages to the Western Oceans 郑和下西洋". People.chinese.cn. Archived from the original on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- Da Gama's First Voyage pg.88

- East Africa and its Invaders pg.38

- Alpers, Edward A. (1976). "Gujarat and the Trade of East Africa, c. 1500-1800". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 9 (1): 35. doi:10.2307/217389. JSTOR 217389.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Nigel (2003). The Return of Cosmopolitan Capital: Globalization, the State and War. I.B.Tauris. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-86064-786-4.

- Barendse, Rene J. (2002). The Arabian Seas: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century: The Indian Ocean World of the Seventeenth Century. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-45835-7.

- The Portuguese period in East Africa – Page 112

- (Africanus), Leo (6 April 1969). "A Geographical Historie of Africa". Theatrum Orbis Terrarum. Retrieved 6 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- Dunn, Ross E. (1987). The Adventures of Ibn Battuta. Berkeley: University of California. pp. 373. ISBN 0-520-05771-6., p. 125

- pg 4 - The quest for an African Eldorado: Sofala, By Terry H. Elkiss

- Northeast African Studies, Volume 2. 1995. p. 24.

- Stanley, Bruce (2007). "Mogadishu". In Dumper, Michael; Stanley, Bruce E. (eds.). Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-57607-919-5.

- The Oxford History of Islam. 1999. p. 502.

- The Numismatic Chronicle. 1978. p. 188.

- Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Volume 1. The Seminar. 1970. p. 42. ISBN 0231107145. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (1996). The New Islamic Dynasties. Columbia University Press. p. 139. ISBN 0231107145. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- Luling, Virginia (2001). Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years. Transaction Publishers. p. 272. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- Ali, Ismail Mohamed (1970). Somalia Today: General Information. Ministry of Information and National Guidance, Somali Democratic Republic. p. 206. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Chittick, H. Neville (1976). An Archaeological Reconnaissance in the Horn: The British-Somali Expedition, 1975. British Institute in Eastern Africa. pp. 117–133.

- Album, Stephen (1993). A Checklist of Popular Islamic Coins. Stephen Album. p. 28. ISBN 0963602403. Retrieved 28 February 2015.