Hindu astrology

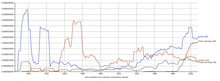

Jyotisha or Jyotishya (from Sanskrit jyotiṣa, from jyóti- "light, heavenly body") is the traditional Hindu system of astrology, also known as Hindu astrology, Indian astrology and more recently Vedic astrology. The term Hindu astrology has been in use as the English equivalent of Jyotiṣa since the early 19th century, whereas Vedic astrology is a relatively recent term, entering common usage in the 1970s with self-help publications on Āyurveda or yoga. Vedanga Jyotishya is one of the earliest texts about astronomy within the Vedas.[1][2][3] However, some authors have claimed that the horoscopic astrology practiced in the Indian subcontinent came from Hellenistic influences, post-dating the Vedic period.[4] Some authors argue that in the mythologies Ramayana and Mahabharata, only electional astrology, omens, dreams and physiognomy are used but there have been several articles and blogs published which cites multiple references in those books about Rashi(zodiac sign) based astrology.

| Astrology |

|---|

New millennium astrological chart |

| Background |

| Traditions |

| Branches |

Following a judgement of the Andhra Pradesh High Court in 2001 which favoured astrology, some Indian universities now offer advanced degrees in Hindu astrology, despite protest from the scientific community. Astrology is rejected as pseudoscience by the scientific community, but the Indian government does not agree.[5][6][7][8][9]

History and core principles

Jyotiṣa is one of the Vedāṅga, the six auxiliary disciplines used to support Vedic rituals.[10]:376 Early jyotiṣa is concerned with the preparation of a calendar to determine dates for sacrificial rituals,[10]:377 with nothing written regarding planets.[10]:377 There are mentions of eclipse-causing "demons" in the Atharvaveda and Chāndogya Upaniṣad, the latter mentioning Rāhu (a shadow entity believed responsible for eclipses and meteors).[10]:382 The term graha, which is now taken to mean planet, originally meant demon.[10]:381 The Ṛigveda also mentions an eclipse-causing demon, Svarbhānu, however the specific term graha was not applied to Svarbhānu until the later Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa.[10]:382

The foundation of Hindu astrology is the notion of bandhu of the Vedas (scriptures), which is the connection between the microcosm and the macrocosm. Practice relies primarily on the sidereal zodiac, which differs from the tropical zodiac used in Western (Hellenistic) astrology in that an ayanāṁśa adjustment is made for the gradual precession of the vernal equinox. Hindu astrology includes several nuanced sub-systems of interpretation and prediction with elements not found in Hellenistic astrology, such as its system of lunar mansions (Nakṣatra). It was only after the transmission of Hellenistic astrology that the order of planets in India was fixed in that of the seven-day week.[10]:383[11] Hellenistic astrology and astronomy also transmitted the twelve zodiacal signs beginning with Aries and the twelve astrological places beginning with the ascendant.[10]:384 The first evidence of the introduction of Greek astrology to India is the Yavanajātaka which dates to the early centuries CE.[10]:383 The Yavanajātaka (lit. "Sayings of the Greeks") was translated from Greek to Sanskrit by Yavaneśvara during the 2nd century CE, and is considered the first Indian astrological treatise in the Sanskrit language.[12] However the only version that survives is the verse version of Sphujidhvaja which dates to AD 270.[10]:383 The first Indian astronomical text to define the weekday was the Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa (born AD 476).[10]:383

According to Michio Yano, Indian astronomers must have been occupied with the task of Indianizing and Sanskritizing Greek astronomy during the 300 or so years between the first Yavanajataka and the Āryabhaṭīya.[10]:388 The astronomical texts of these 300 years are lost.[10]:388 The later Pañcasiddhāntikā of Varāhamihira summarizes the five known Indian astronomical schools of the sixth century.[10]:388 Indian astronomy preserved some of the older pre-Ptolemaic elements of Greek astronomy.[10]:389

The main texts upon which classical Indian astrology is based are early medieval compilations, notably the Bṛhat Parāśara Horāśāstra, and Sārāvalī by Kalyāṇavarma. The Horāshastra is a composite work of 71 chapters, of which the first part (chapters 1–51) dates to the 7th to early 8th centuries and the second part (chapters 52–71) to the later 8th century. The Sārāvalī likewise dates to around 800 CE.[13] English translations of these texts were published by N. N. Krishna Rau and V. B. Choudhari in 1963 and 1961, respectively.

Modern Hindu astrology

Astrology remains an important facet of folk belief in the contemporary lives of many Hindus. In Hindu culture, newborns are traditionally named based on their jyotiṣa charts (Kundali), and astrological concepts are pervasive in the organization of the calendar and holidays, and in making major decisions such as those about marriage, opening a new business, or moving into a new home. Many Hindus believe that heavenly bodies, including the planets, have an influence throughout the life of a human being, and these planetary influences are the "fruit of karma". The Navagraha, planetary deities, are considered subordinate to Ishvara (the Hindu concept of a supreme being) in the administration of justice. Thus, it is believed that these planets can influence earthly life.[14]

Status of astrology

Astrology retains a position among the sciences in modern India.[15]

India's University Grants Commission and Ministry of Human Resource Development decided to introduce "Jyotir Vigyan" (i.e. jyotir vijñāna) or "Vedic astrology" as a discipline of study in Indian universities, stating that "vedic astrology is not only one of the main subjects of our traditional and classical knowledge but this is the discipline, which lets us know the events happening in human life and in universe on time scale."[16] The decision was backed by a 2001 judgement of the Andhra Pradesh High Court, and some Indian universities offer advanced degrees in astrology.[17][18] This was met with widespread protests from the scientific community in India and Indian scientists working abroad.[19] A petition sent to the Supreme Court of India stated that the introduction of astrology to university curricula is "a giant leap backwards, undermining whatever scientific credibility the country has achieved so far".[16]

In 2004, the Supreme Court dismissed the petition,[20][21] concluding that the teaching of astrology did not qualify as the promotion of religion.[22][23] In February 2011, the Bombay High Court referred to the 2004 Supreme Court ruling when it dismissed a case which had challenged astrology's status as a science.[24] As of 2014, despite continuing complaints by scientists,[25][26] astrology continues to be taught at various universities in India,[23][27] and there is a movement in progress to establish a national Vedic University to teach astrology together with the study of tantra, mantra, and yoga.[28]

Elements

There are sixteen Varga (Sanskrit: varga, 'part, division'), or divisional, charts used in Hindu astrology:[29]:61–64

Rāśi – zodiacal signs

The Nirayana, or sidereal zodiac, is an imaginary belt of 360 degrees, which, like the Sāyana, or tropical zodiac, is divided into 12 equal parts. Each part (of 30 degrees) is called a sign or rāśi (Sanskrit: 'part'). Vedic (Jyotiṣa) and Western zodiacs differ in the method of measurement. While synchronically, the two systems are identical, Jyotiṣa primarily uses the sidereal zodiac (in which stars are considered to be the fixed background against which the motion of the planets is measured), whereas most Western astrology uses the tropical zodiac (the motion of the planets is measured against the position of the Sun on the spring equinox). After two millennia, as a result of the precession of the equinoxes, the origin of the ecliptic longitude has shifted by about 22 degrees. As a result, the placement of planets in the Jyotiṣa system is roughly aligned with the constellations, while tropical astrology is based on the solstices and equinoxes.

| No. | Sanskrit[30] | Transliteration | Representation | English | Punjabi | Bengali | Kannada | Odia | Telugu | Tamil | Malayalam | Element | Quality | Ruling Astrological Body |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | मेष | Meṣa | ram | Aries | ਮੇਖ | মেষ | ಮೇಷ | ମେଷ | మేషము | மேஷம் | മേടം | Fire | Chara (movable) | Mars |

| 2 | वृषभ | Vṛṣabha | bull | Taurus | ਬ੍ਰਿਖ | বৃষ | ವೃಷಭ | ବୃଷ | వృషభము | ரிஷபம் | ഇടവം | Earth | Sthira (fixed) | Venus |

| 3 | मिथुन | Mithuna | twins | Gemini | ਮਿਥੁਨ | মিথুন | ಮಿಥುನ | ମିଥୁନ | మిథునము | மிதுனம் | മിഥുനം | Air | Dvisvabhava (dual) | Mercury |

| 4 | कर्क | Karka | crab | Cancer | ਕਰਕ | কর্কট | ಕರ್ಕಾಟಕ | କର୍କଟ | కర్కాటకము | கடகம் | കർക്കടകം | Water | Chara (movable) | Moon |

| 5 | सिंह | Siṃha | lion | Leo | ਸਿੰਘ | সিংহ | ಸಿಂಹ | ସିଂହ | సింహము | சிம்மம் | ചിങ്ങം | Fire | Sthira (fixed) | Sun |

| 6 | कन्या | Kanyā | virgin girl | Virgo | ਕੰਨਿਆ | কন্যা | ಕನ್ಯಾ | କନ୍ୟା | కన్య | கன்னி | കന്നി | Earth | Dvisvabhava (dual) | Mercury |

| 7 | तुला | Tulā | balance | Libra | ਤੁਲਾ | তুলা | ತುಲಾ | ତୁଳା | తుల | துலாம் | തുലാം | Air | Chara (movable) | Venus |

| 8 | वृश्चिक | Vṛścika | scorpion | Scorpio | ਬ੍ਰਿਸ਼ਚਕ | বৃশ্চিক | ವೃಶ್ಚಿಕ | ବିଛା | వృచ్చికము | விருச்சிகம் | വൃശ്ചികം | Water | Sthira (fixed) | Mars |

| 9 | धनुष | Dhanuṣa | bow and arrow | Sagittarius | ਧਨੁ | ধনু | ಧನು | ଧନୁ | ధనుస్సు | தனுசு | ധനു | Fire | Dvisvabhava (dual) | Jupiter |

| 10 | मकर | Makara | goat | Capricorn | ਮਕਰ | মকর | ಮಕರ | ମକର | మకరము | மகரம் | മകരം | Earth | Chara (movable) | Saturn |

| 11 | कुम्भ | Kumbha | water-bearer | Aquarius | ਕੁੰਭ | কুম্ভ | ಕುಂಭ | କୁମ୍ଭ | కుంభము | கும்பம் | കുംഭം | Air | Sthira (fixed) | Saturn |

| 12 | मीन | Mīna | fishes | Pisces | ਮੀਨ | মীন | ಮೀನ | ମୀନ | మీనము | மீனம் | മീനം | Water | Dvisvabhava (dual) | Jupiter |

Nakṣhatras – lunar mansions

The nakshatras or lunar mansions are 27 equal divisions of the night sky used in Hindu astrology, each identified by its prominent star(s).[29]:168

Historical (medieval) Hindu astrology enumerated either 27 or 28 nakṣatras. In modern astrology, a rigid system of 27 nakṣatras is generally used, each covering 13° 20′ of the ecliptic. The missing 28th nakshatra is Abhijeeta. Each nakṣatra is divided into equal quarters or padas of 3° 20′. Of greatest importance is the Abhiśeka Nakṣatra, which is held as king over the other nakṣatras. Worshipping and gaining favour over this nakṣatra is said to give power to remedy all the other nakṣatras, and is of concern in predictive astrology and mitigating Karma.

The 27 nakshatras are:

- Ashvini

- Bharni

- Krittika

- Rohini

- Mrighashirsha

- Ardra or Aarudhra

- Punarvasu

- Pushya

- Aslesha

- Magha

- Purva Phalguni

- Uttara Phalguni

- Hasta

- Chitra

- Swati

- Vishakha

- Anuradha

- Jyeshtha

- Moola

- Purvashada

- Uttarashada

- Shravana

- Dhanishta

- Shatabhishak

- Purva Bhadra

- Uttara Bhadra

- Revati

Daśās – planetary periods

The word dasha (Devanāgarī: दशा, Sanskrit,daśā, 'planetary period') means 'state of being' and it is believed that the daśā largely governs the state of being of a person. The Daśā system shows which planets may be said to have become particularly active during the period of the Daśā. The ruling planet (the Daśānātha or 'lord of the Daśā') eclipses the mind of the person, compelling him or her to act per the nature of the planet.

There are several dasha systems, each with its own utility and area of application. There are Daśās of grahas (planets) as well as Daśās of the Rāśis (zodiac signs). The primary system used by astrologers is the Viṁśottarī Daśā system, which has been considered universally applicable in the kaliyuga to all horoscopes.

The first Mahā-Daśā is determined by the position of the natal Moon in a given Nakṣatra. The lord of the Nakṣatra governs the Daśā. Each Mahā-Dāśā is divided into sub-periods called bhuktis, or antar-daśās, which are proportional divisions of the maha-dasa. Further proportional sub-divisions can be made, but error margins based on accuracy of the birth time grow exponentially. The next sub-division is called pratyantar-daśā, which can in turn be divided into sookshma-antardasa, which can in turn be divided into praana-antardaśā, which can be sub-divided into deha-antardaśā. Such sub-divisions also exist in all other Daśā systems.

Grahas – planets

The Navagraha (nava; Devanāgarī: नव, Sanskrit: nava, "nine"; graha; Devanāgarī: ग्रह, Sanskrit: graha, 'planet')[31]) describe nine celestial bodies used in Hindu astrology.[29]:38–51

The Navagraha are said to be forces that capture or eclipse the mind and the decision making of human beings, thus the term graha. When the grahas are active in their Daśās or periodicities they are said to be particularly empowered to direct the affairs of people and events.

Rahu and Ketu correspond to the points where the moon crosses the ecliptic plane (known as the ascending and descending nodes of the moon). Classically known in Indian and Western astrology as the "head and tail of the dragon", these planets are represented as a serpent-bodied demon beheaded by the Sudarshan Chakra of Vishnu after attempting to swallow the sun. They are primarily used to calculate the dates of eclipses. They are described as "shadow planets" because they are not visible in the night sky. They have an orbital cycle of 18 years and are always 180 degrees from each other.

Gocharas – transits

A natal chart shows the position of the grahas at the moment of birth. Since that moment, the grahas have continued to move around the zodiac, interacting with the natal chart grahas. This period of interaction is called gochara (Sanskrit: gochara, 'transit').[29]:227

The study of transits is based on the transit of the Moon (Chandra), which spans roughly two days, and also on the movement of Mercury (Budha) and Venus (Śukra) across the celestial sphere, which is relatively fast as viewed from Earth. The movement of the slower planets – Jupiter (Guru), Saturn (Śani) and Rāhu–Ketu — is always of considerable importance. Astrologers study the transit of the Daśā lord from various reference points in the horoscope.

The transit phase alway makes an impact on the lives of humans on earth which can be positive or negative however as per the astrologers the impact of transits can be nuetralised with remedies.

Yogas – planetary combinations

In Hindu astronomy, yoga (Sanskrit: yoga, 'union') is a combination of planets placed in a specific relationship to each other.[29]:265

Rāja yogas are perceived as givers of fame, status and authority, and are typically formed by the association of the Lord of Keṅdras ('quadrants'), when reckoned from the Lagna ('Ascendant'), and the Lords of the Trikona ('trines', 120 degrees—first, fifth and ninth houses). The Rāja yogas are culminations of the blessings of Viṣṇu and Lakṣmī. Some planets, such as Mars for Leo Lagna, do not need another graha (or Navagraha, 'planet') to create Rājayoga, but are capable of giving Rājayoga by themselves due to their own lordship of the 4th Bhāva ('astrological house') and the 9th Bhāva from the Lagna, the two being a Keṅdra ('angular house'—first, fourth, seventh and tenth houses) and Trikona Bhāva respectively.

Dhana Yogas are formed by the association of wealth-giving planets such as the Dhaneśa or the 2nd Lord and the Lābheśa or the 11th Lord from the Lagna. Dhana Yogas are also formed due to the auspicious placement of the Dārāpada (from dara, 'spouse' and pada, 'foot'—one of the four divisions—3 degrees and 20 minutes—of a Nakshatra in the 7th house), when reckoned from the Ārūḍha Lagna (AL). The combination of the Lagneśa and the Bhāgyeśa also leads to wealth through the Lakṣmī Yoga.

Sanyāsa Yogas are formed due to the placement of four or more grahas, excluding the Sun, in a Keṅdra Bhāva from the Lagna.

There are some overarching yogas in Jyotiṣa such as Amāvasyā Doṣa, Kāla Sarpa Yoga-Kāla Amṛta Yoga and Graha Mālika Yoga that can take precedence over Yamaha yogar planetary placements in the horoscope.

Bhāvas – houses

The Hindu Jātaka or Janam Kundali or birth chart, is the Bhāva Chakra (Sanskrit: 'division' 'wheel'), the complete 360° circle of life, divided into houses, and represents a way of enacting the influences in the wheel. Each house has associated kāraka (Sanskrit: 'significator') planets that can alter the interpretation of a particular house.[29]:93–167 Each Bhāva spans an arc of 30° with twelve Bhāvas in any chart of the horoscope. These are a crucial part of any horoscopic study since the Bhāvas, understood as 'state of being', personalize the Rāśis/ Rashis to the native and each Rāśi/ Rashi apart from indicating its true nature reveals its impact on the person based on the Bhāva occupied. The best way to study the various facets of Jyotiṣa is to see their role in chart evaluation of actual persons and how these are construed.

Dṛṣṭis – aspects

Drishti (Sanskrit: Dṛṣṭi, 'sight') is an aspect to an entire house. Grahas cast only forward aspects, with the furthest aspect being considered the strongest. For example, Mars aspects the 4th, 7th, and 8th houses from its position, and its 8th house aspect is considered more powerful than its 7th aspect, which is in turn more powerful than its 4th aspect.[29]:26–27

The principle of Dristi (aspect) was devised on the basis of the aspect of an army of planets as deity and demon in a war field.[32][33] Thus the Sun, a deity king with only one full aspect, is more powerful than the demon king Saturn, which has three full aspects.

Aspects can be cast both by the planets (Graha Dṛṣṭi) and by the signs (Rāśi Dṛṣṭi). Planetary aspects are a function of desire, while sign aspects are a function of awareness and cognizance.

There are some higher aspects of Graha Dṛṣṭi (planetary aspects) that are not limited to the Viśeṣa Dṛṣṭi or the special aspects. Rāśi Dṛṣṭi works based on the following formulaic structure: all movable signs aspect fixed signs except the one adjacent, and all dual and mutable signs aspect each other without exception.

Science

Astrology has been rejected by the scientific community as having no explanatory power for describing the universe. Scientific testing of astrology has been conducted, and no evidence has been found to support any of the premises or purported effects outlined in astrological traditions.[34]:424 There is no mechanism proposed by astrologers through which the positions and motions of stars and planets could affect people and events on Earth.

Astrologers in Indian astrology make grand claims without taking adequate controls into consideration. Saturn was in Aries in 1909, 1939 and 1968, yet the astrologer Bangalore Venkata Raman claimed that "when Saturn was in Aries in 1939 England had to declare war against Germany", ignoring the two other dates.[35] Astrologers regularly fail in attempts to predict election results in India, and fail to predict major events such as the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Predictions by the head of the Indian Astrologers Federation about war between India and Pakistan in 1982 also failed.[35]

In 2000, when several planets happened to be close to one another, astrologers predicted that there would be catastrophes, volcanic eruptions and tidal waves. This caused an entire sea-side village in the Indian state of Gujarat to panic and abandon their houses. The predicted events did not occur and the vacant houses were burgled.[36]

See also

- Archaeoastronomy and Vedic chronology

- Hindu calendar

- Hindu cosmology

- History of astrology

- Indian astronomy

- Jyotisha

- Jyotiṣa resources

- Nadi astrology

- Panchanga

- Synoptical astrology

- Hindu units of measurement

References

- Thompson, Richard L. (2004). Vedic Cosmography and Astronomy. pp. 9–240.

- Jha, Parmeshwar (1988). Āryabhaṭa I and his contributions to mathematics. p. 282.

- Puttaswamy, T.K. (2012). Mathematical Achievements of Pre-Modern Indian Mathematicians. p. 1.

- Pingree(1981), p.67ff, 81ff, 101ff

- Thagard, Paul R. (1978). "Why Astrology is a Pseudoscience" (PDF). Proceedings of the Biennial Meeting of the Philosophy of Science Association. 1: 223–234.

- Astrology. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Sven Ove Hansson; Edward N. Zalta. "Science and Pseudo-Science". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "Astronomical Pseudo-Science: A Skeptic's Resource List". Astronomical Society of the Pacific.

- Hartmann, P.; Reuter, M.; Nyborga, H. (May 2006). "The relationship between date of birth and individual differences in personality and general intelligence: A large-scale study". Personality and Individual Differences. 40 (7): 1349–1362. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.017.

To optimise the chances of finding even remote relationships between date of birth and individual differences in personality and intelligence we further applied two different strategies. The first one was based on the common chronological concept of time (e.g. month of birth and season of birth). The second strategy was based on the (pseudo-scientific) concept of astrology (e.g. Sun Signs, The Elements, and astrological gender), as discussed in the book Astrology: Science or superstition? by Eysenck and Nias (1982).

- Flood, Gavin. Yano, Michio. 2003. The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Malden: Blackwell.

- Flood, p. 382

- Mc Evilley "The shape of ancient thought", p. 385 ("The Yavanajātaka is the earliest surviving Sanskrit text in horoscopy, and constitute the basis of all later Indian developments in horoscopy", himself quoting David Pingree "The Yavanajātaka of Sphujidhvaja" p. 5)

- David Pingree, Jyotiḥśāstra (J. Gonda (Ed.) A History of Indian Literature, Vol VI Fasc 4), p. 81

- Karma, an anthropological inquiry, pg. 134, at Google Books

- "In countries such as India, where only a small intellectual elite has been trained in Western physics, astrology manages to retain here and there its position among the sciences." David Pingree and Robert Gilbert, "Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times" Encyclopædia Britannica 2008

- Supreme Court questions 'Jyotir Vigyan', Times of India, 3 September 2001 timesofindia.indiatimes.com

- Mohan Rao, Female foeticide: where do we go? Indian Journal of Medical Ethics Oct-Dec2001-9(4), issuesinmedicalethics.org Archived 27 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- T. Jayaraman, A judicial blow, Frontline Volume 18 – Issue 12, Jun. 09 – 22, 2001 hinduonnet.com

- T. Jayaraman, A judicial blow, Frontline Volume 18 – Issue 12, June 09 – 22, 2001 hinduonnet.com Archived 28 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Astrology On A Pedestal, Ram Ramachandran, Frontline Volume 21, Issue 12, Jun. 05 - 18, 2004

- Introduction of Vedic astrology courses in varsities upheld, The Hindu, Thursday, May 06, 2004

- "Supreme Court: Bhargava v. University Grants Commission, Case No.: Appeal (civil) 5886 of 2002". Archived from the original on 12 March 2005.

- "Introduction of Vedic astrology courses in universities upheld". The Hindu. 5 May 2004. Archived from the original on 23 September 2004.

- "Astrology is a science: Bombay HC". The Times of India. 3 February 2011. Archived from the original on 6 February 2011.

- "'Integrate Indian medicine with modern science'". The Hindu. 26 October 2003. Archived from the original on 13 November 2003.

- Narlikar, Jayant V. (2013). "An Indian Test of Indian Astrology". Skeptical Inquirer. 37 (2). Archived from the original on 23 July 2013.

- "People seek astrological advise from Banaras Hindu University experts to tackle health issues". The Times of India. 13 February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014.

- "Set-up Vedic university to promote astrology". The Times of India. 9 February 2013. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013.

- Sutton, Komilla (1999). The Essentials of Vedic Astrology, The Wessex Astrologer Ltd, England

- Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Sanskrit-English Dictionary by Monier-Williams, (c) 1899

- Sanat Kumar Jain, 'Astrology a science or myth', Atlantic Publishers, New Delhi.

- Sanat Kumar Jain, "Jyotish Kitna Sahi Kitna Galat' (Hindi).

- Zarka, Philippe (2011). "Astronomy and astrology" (PDF). Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union. 5 (S260): 420–425. doi:10.1017/S1743921311002602.

- V. Narlikar, Jayant (March–April 2013). "An Indian Test of Indian Astrology". Skeptical Inquirer. 37.2.

- Narlikar, Jayant V. (2009). "Astronomy, pseudoscience and rational thinking". In Jay Pasachoff; John Percy (eds.). Teaching and Learning Astronomy: Effective Strategies for Educators Worldwide. Cambridge University Press. pp. 164–165. Retrieved 19 July 2015.

Bibliography

- Burgess, Ebenezer (1866). "On the Origin of the Lunar Division of the Zodiac represented in the Nakshatra System of the Hindus". Journal of the American Oriental Society.

- Chandra, Satish (2002). "Religion and State in India and Search for Rationality". Social Scientist

- Fleet, John F. (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 491–501.

- Jain, Sanat K. "Astrology a science or myth", New Delhi, Atlasntic Publishers 2005 - highlighting how every principle like sign lord, aspect, friendship-enmity, exalted-debilitated, Mool trikon, dasha, Rahu-Ketu, etc. were framed on the basis of the ancient concept that Sun is nearer than the Moon from the Earth, etc.

- Pingree, David (1963). "Astronomy and Astrology in India and Iran". Isis – Journal of The History of Science Society. pp. 229–246.

- Pingree, David (1981). Jyotiḥśāstra in J. Gonda (ed.) A History of Indian Literature. Vol VI. Fasc 4. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz.

- Pingree, David and Gilbert, Robert (2008). "Astrology; Astrology In India; Astrology in modern times". Encyclopædia Britannica. online ed.

- Plofker, Kim. (2008). "South Asian mathematics; The role of astronomy and astrology". Encyclopædia Britannica, online ed.

- Whitney, William D. (1866). "On the Views of Biot and Weber Respecting the Relations of the Hindu and Chinese Systems of Asterisms", Journal of the American Oriental Society

Popular treatments:

- Frawley, David (2000). Astrology of the Seers: A Guide to Vedic (Hindu) Astrology. Twin Lakes Wisconsin: Lotus Press. ISBN 0-914955-89-6

- Frawley, David (2005). Ayurvedic Astrology: Self-Healing Through the Stars. Twin Lakes Wisconsin: Lotus Press. ISBN 0-940985-88-8