German colonial empire

The German colonial empire (German: Deutsches Kolonialreich) constituted the overseas colonies, dependencies and territories of Imperial Germany. Unified in the early 1870s, the chancellor of this time period was Otto von Bismarck. Short-lived attempts of colonization by individual German states had occurred in preceding centuries, but crucial colonial efforts only began in 1884 with the Scramble for Africa. Claiming much of the left-over uncolonized areas in the Scramble for Africa, Germany managed to build the third-largest colonial empire at the time, after the British and French.[2]

German Colonial Empire Deutsches Kolonialreich | |

|---|---|

| 1884–1918 | |

Flag

Coat of arms

| |

German colonies and protectorates in 1914 | |

| Status | Colonial empire |

| Capital | Berlin |

| Common languages | German Local: Swahili, Arabic (East African colonies) Papuan languages (German New Guinea) Samoan (German Samoa) |

| History | |

| 1884 | |

| 1888 | |

| 1890 | |

| 1904 | |

| 1905 | |

• Disestablished | 1918 |

| 28 June 1919 | |

| Area | |

| 1912[1] (not including Imperial Germany proper) | 2,658,161 km2 (1,026,322 sq mi) |

Germany lost control of its colonial empire when the First World War began in 1914, in which many of its colonies were seized by the Allies during the first weeks of the war. However, a number of German colonial military units held out for a while longer: German South West Africa surrendered in 1915, Kamerun in 1916 and German East Africa in 1918. In the case of German East Africa, the defenders under the command of Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, had engaged a guerrilla war against British colonial and Portuguese forces and did not surrender until after the end of the war.

Germany's colonial empire was officially confiscated with the Treaty of Versailles after Germany's defeat in the war and each colony became a League of Nations mandate under the supervision (but not ownership) of one of the victorious powers. The German colonial empire ceased to exist in 1919.[3] Plans to regain their lost colonial possessions persisted through the Second World War, with many at the time suspecting that this was a goal of the Third Reich all along.[4]

Origins

German unification

Until their 1871 unification, the German states had not concentrated on the development of a navy, and this essentially had precluded German participation in earlier imperialist scrambles for remote colonial territory – the so-called "place in the sun". Germany seemed destined to play catch-up. The German states prior to 1870 had retained separate political structures and goals, and German foreign policy up to and including the age of Otto von Bismarck concentrated on resolving the "German question" in Europe and securing German interests on the continent.[5] However, by 1891 they were mostly united under Prussian rule.[6] They also sought a more clear cut "German" state, and saw colonies as a good way to achieve that.[7]

Scramble for colonies

Many Germans in the late 19th century viewed colonial acquisitions as a true indication of having achieved nationhood. Public opinion eventually arrived at an understanding that prestigious African and Pacific colonies went hand-in-hand with dreams of a High Seas Fleet. Both aspirations would become reality, nurtured by a press replete with Kolonialfreunde [supporters of colonial acquisitions] and by a myriad of geographical associations and colonial societies. Bismarck and many deputies in the Reichstag had no interest in colonial conquests merely to acquire square miles of territory.[8]

In 1844 Rhenish Aristocrats attempted to set up a German colony in the independent state of Texas. about 7400 settlers were involved. Around half of them died, the venture was a complete failure. A constant lack of supplies and land didn't help, and the next year Texas joined the United States.[9]

In essence, Bismarck's colonial motives were obscure as he had said repeatedly "... I am no man for colonies"[10] and "remained as contemptuous of all colonial dreams as ever."[11] However, in 1884 he consented to the acquisition of colonies by the German Empire, in order to protect trade, safeguard raw materials and export markets and take advantage of opportunities for capital investment, among other reasons.[12] In the very next year Bismarck shed personal involvement when "he abandoned his colonial drive as suddenly and casually as he had started it" as if he had committed an error in judgment that could confuse the substance of his more significant policies.[13] "Indeed, in 1889, [Bismarck] tried to give German South-West Africa away to the British. It was, he said, a burden and an expense, and he would like to saddle someone else with it."[14]

Before this, Germans had traditions of foreign sea-borne trade dating back to the Hanseatic League; a tradition of German emigration that existed (eastward in the direction of Russia and Transylvania and westward to the Americas); and North German merchants and missionaries showed interest in overseas engagements. The Hanseatic republics of Hamburg and Bremen sent traders across the globe. These trading houses conducted themselves as successful Privatkolonisatoren [independent colonizers] and concluded treaties and land purchases in Africa and the Pacific with chiefs and or other tribal leaders. These early agreements with local entities later formed the basis for annexation treaties, diplomatic support and military protection by the German government.[15]

Acquisition of colonies

The German Colonial empire got its start around 1884, and in those years they acquired several territories: German East Africa, German South-West Africa, German Cameroon, and Togoland in Africa. Germany was also active in the Pacific, annexing a series of islands that would be called German New Guinea. The northeastern region of New Guinea was called Kaiser-Wilhelmsland, the Bismarck Archipelago to the islands east, this also contained two larger islands named New Mecklenburg and New Pomerania, they also acquired the Northern Solomon Islands. These islands were given the status of protectorate.[16]

Company land acquisitions and stewardship

The rise of German imperialism and colonialism coincided with the latter stages of the "Scramble for Africa" during which enterprising German individuals, rather than government entities, competed with other already established colonies and colonialist entrepreneurs. With the Germans joining the race for the last uncharted territories in Africa and the Pacific that had not yet been carved up, competition for colonies thus involved major European nations and several lesser powers.

The German effort included the first commercial enterprises in the 1850s and 1860s in West Africa, East Africa, the Samoan Islands and the unexplored north-east quarter of New Guinea with adjacent islands.[17] German traders and merchants began to establish themselves in the African Cameroon delta and the mainland coast across from Zanzibar.[18] At Apia and the settlements Finschhafen, Simpsonhafen and the islands Neu-Pommern and Neu-Mecklenburg, trading companies newly fortified with credit began expansion into coastal landholding.[19] Large African inland acquisitions followed — mostly to the detriment of native inhabitants. In eastern Africa the imperialist and "man-of-action" Karl Peters accumulated vast tracts of land for his colonization group, "emerging from the bush with X-marks [affixed by unlettered tribal chiefs] on documents ... for some 60 thousand square miles of the Zanzibar Sultanate’s mainland property."[20] Such exploratory missions required security measures that could be solved with small private, armed contingents recruited mainly in the Sudan and usually led by adventurous former military personnel of lower rank. Brutality, hanging and flogging prevailed during these land-grab expeditions under Peters’ control as well as others as no-one "held a monopoly in the mistreatment of Africans."[21]

As Bismarck was converted to the colonial idea by 1884, he favored "chartered company" land management rather than establishment of colonial government due to financial considerations.[22] Although temperate zone cultivation flourished, the demise and often failure of tropical low-land enterprises contributed to changing Bismarck's view. He reluctantly acquiesced to pleas for help to deal with revolts and armed hostilities by often powerful rulers whose lucrative slaving activities seemed at risk. German native military forces initially engaged in dozens of punitive expeditions to apprehend and punish freedom fighters, at times with British assistance.[23] The author Charles Miller offers the theory that the Germans had the handicap of trying to colonize African areas inhabited by aggressive tribes,[24] whereas their colonial neighbours had more docile peoples to contend with. At that time, the German penchant for giving muscle priority over patience contributed to continued unrest. Several of the African colonies remained powder kegs throughout this phase (and beyond). The transition to official acceptance of colonialism and to colonial government thus occurred during the last quarter of Bismarck's tenure of office.[25]

Growth

In the first years of the 20th-century shipping lines had established scheduled services with refrigerated holds and agricultural products from the colonies, exotic fruits and spices, were sold to the public in Germany. The colonies were romanticized. Geologists and cartographers explored what were the unmarked regions on European maps, identifying mountains and rivers, and demarcating boundaries. Hermann Detzner and one Captain Nugent, R.A., had charge of a joint project to demarcate the British and German frontiers of Cameroon, which was published in 1913.[26] Travelers and newspaper reporters brought back stories of black and brown natives serving German managers and settlers. There were also suspicions and reports of colonial malfeasance, corruption and brutality in some protectorates, and Lutheran and Roman Catholic missionaries dispatched disturbing reports to their mission headquarters in Germany.[27]

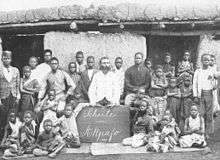

German colonial diplomatic efforts remained commercially inspired, "the colonial economy was thriving ... and roads, railways, shipping and telegraph communications were up to the minute."[28] Overhaul of the colonial administrative apparatus thus set the stage for the final and most promising period of German colonialism.[29] Bernhard Dernburg's declaration that the indigenous population in the protectorates "was the most important factor in our colonies" was affirmed by new laws. The use of forced, unpaid labor went on the books as a criminal offense.[30] Governor Wilhelm Solf of Samoa would call the islanders "unsere braunen Schützlinge" [our brown charges], who could be guided but not forced.[31] Heinrich Schnee in East Africa proclaimed that "the dominant feature of my administration [will be] ... the welfare of the natives entrusted into my care."[32] Idealists often volunteered for selection and appointment to government posts, while others with an entrepreneurial bent labored to swell the dividends at home for the Hanseatic trading houses and shipping lines. Subsequent historians would commend German colonialism in those years as "an engine of modernization with far-reaching effects for the future."[33] The native population was forced into unequal treaties by the German colonial governments. This led to the local tribes and natives losing their influence and power and eventually forced some of them to become slave laborers. Although slavery was partially outlawed in 1905 by Germany, this caused a great deal of resentment and led eventually to revolts by the native population. The result was several military and genocidal campaigns by the Germans against the natives.[34] Political and economic subjugation of Herero and Nama was envisioned. Both the colonial authorities and settlers were of the opinion that native Africans were to be a lower class, their land seized and handed over to settlers and companies, while the remaining population was to be put in reservations; the Germans planned to make a colony inhabited predominately by whites: a "new African Germany".[35]

The established merchants and plantation operators in the African colonies frequently managed to sway government policies. Capital investments by banks were secured with public funds of the imperial treasury to minimize risk. Dernburg, as a former banker, facilitated such thinking; he saw his commission to also turn the colonies into paying propositions. Every African protectorate built rail lines to the interior,[36] every colony in Africa and the Pacific established the beginnings of a public school system,[37] and every colony built and staffed hospitals.[38] Whatever the Germans constructed in their colonies was made to last.[39]

Dar es Salaam evolved into "the showcase city of all of tropical Africa,"[39] Lomé grew into the "prettiest city in western Africa",[40] and Tsingtao, China was, "in miniature, as German a city as Hamburg or Bremen".[41] For indigenous populations in some colonies native agricultural holdings were encouraged and supported.[42]

End of the German colonial empire

Conquest in World War I

In the years before the outbreak of the World War, British colonial officers viewed the Germans as deficient in "colonial aptitude", but "whose colonial administration was nevertheless superior to those of the other European states".[44] Anglo-German colonial issues in the decade before 1914 were minor and both empires, the British and German, took conciliatory attitudes. Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey, considered still a moderate in 1911, was willing to "study the map of Africa in a pro-German spirit".[45] Britain further recognized that Germany really had little of value to offer in territorial transactions; however, advice to Grey and Prime Minister H. H. Asquith hardened by early 1914 "to stop the trend of what the advisers considered Germany’s taking and Britain’s giving."[46]

Once war was declared in late July 1914 Britain and its allies promptly moved against the colonies. The public was informed that German colonies were a threat because "Every German colony has a powerful wireless station — they will talk to one another across the seas, and at every opportunity they [German ships] will dash from cover to harry and destroy our commerce, and maybe, to raid our coasts."[47] The British position that Germany was a uniquely brutal and cruel colonial power originated during the war; it had not been said during peacetime.[48]

In the Pacific, Britain's ally Japan declared war on Germany in 1914 and quickly seized several of Germany's island colonies, the Mariana, Caroline and Marshall Islands, with virtually no resistance.

By 1916 only in remote jungle regions in East Africa did the German forces hold out. South Africa's J.C. Smuts, now in Britain's small War Cabinet, spoke of German schemes for world power, militarisation and exploitation of resources, indicating Germany threatened western civilisation itself. Smuts' warnings were repeated in the press. The idea took hold that they should not be returned to Germany after the war.[49]

Confiscation

Germany's overseas empire was dismantled following defeat in World War I. With the concluding Treaty of Versailles, Article 22, German colonies were transformed into League of Nations mandates and divided between Belgium, the United Kingdom, and certain British Dominions, France and Japan with the determination not to see any of them returned to Germany — a guarantee secured by Article 119.[50]

In Africa, the United Kingdom and France divided German Kamerun (Cameroons) and Togoland. Belgium gained Ruanda-Urundi in northwestern German East Africa, the United Kingdom obtained by far the greater landmass of this colony, thus gaining the "missing link" in the chain of British possessions stretching from South Africa to Egypt (Cape to Cairo), and Portugal received the Kionga Triangle, a sliver of German East Africa. German South-West Africa was taken under mandate by the Union of South Africa.[51] In terms of the population of 12.5 million people in 1914, 42 percent were transferred to mandates of Britain and its dominions. 33 percent to France, and 25 percent to Belgium.[52]

In the Pacific, Japan gained Germany's islands north of the equator (the Marshall Islands, the Carolines, the Marianas, the Palau Islands) and Kiautschou in China. German Samoa was assigned to New Zealand; German New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago and Nauru[53] went to Australia as mandates.[54]

British placement of surrogate responsibility for former German colonies on white-settler dominions was at the time determined to be the most expedient option for the British government — and an appropriate reward for the Dominions having fulfilled their "great and urgent imperial service" through military intervention at the behest of and for Great Britain.[55] It also meant that British colonies now had colonies of their own — which was very much influenced at the Paris proceedings by W.M. Hughes, William Massey, and Louis Botha, the prime ministers of Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.[56] The principle of "self-determination" embodied in the League of Nations covenant was not considered to apply to these colonies and was "regarded as meaningless".[57] To "allay President [Woodrow] Wilson's suspicions of British imperialism", the system of "mandates" was drawn up and agreed to by the British War Cabinet (with the French and Italians in tow),[58] a device by which conquered enemy territory would be held not as a possession but as "sacred trusts".[57] But "far from envisaging the eventual independence of the [former] German colonies, Allied statesmen at the Paris Conference regarded 1919 as the renewal, not the end, of an imperial era."[57] In deliberations the British "War Cabinet had confidence that natives everywhere would opt for British rule"; however, the cabinet acknowledged "the necessity to prove that its policy toward the German colonies was not motivated by aggrandizement" since the Empire was seen by America as a "land devouring octopus"[59] with a "voracious territorial appetite".[60]

Epilogue

President Wilson saw the League of Nations as "'residuary trustee' for the [German] colonies" captured and occupied by "rapacious conquerors".[61] The victors retained the German overseas possessions and did so with the belief that Australian, Belgian, British, French, Japanese, New Zealand, Portuguese and South African rule was superior to Germany's.[62] Several decades later during the collapse of the then existing colonial empires, Africans and Asians cited the same arguments that had been used by the Allies against German colonial rule — they now simply demanded "to stand by themselves".[63]

In the 1920s, some individuals and the German Colonial Society fought for the idea of colonialism. Settlement in Africa was not popular and was not a focus for Hitler. Established in 1936, the Reichskolonialbund under Franz Ritter von Epp absorbed all colonial organizations and was meant to raise pro-colonial sentiments, public interest in former German colonies, and take part in political agitation. However, with the onset of World War II the organization entered a decline, before being disbanded by decree in 1943 for "activity irrelevant to the war".

There are hardly any special ties between modern Germany and its former colonies; for example, there is no postcolonial league comparable to the British Commonwealth of Nations or French Francophonie. In stark contrast with French and English, both of which are widely spoken across the continent by those of both African and European ancestry, the German language is not a significant language in Africa even within former colonies—although it is spoken by a significant minority of the population of Namibia. Germany cooperates economically and culturally with many countries in Africa and Asia, independent of colonial history.

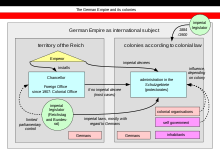

Administration and colonial policies

Colonial governments

Bismarck's successor in 1890, Leo von Caprivi, was willing to maintain the colonial burden of what already existed, but opposed new ventures.[64] Others who followed, especially Bernhard von Bülow, as foreign minister and chancellor, sanctioned the acquisition of the Pacific Ocean colonies and provided substantial treasury assistance to existing protectorates to employ administrators, commercial agents, surveyors, local "peacekeepers" and tax collectors. Kaiser Wilhelm II understood and lamented his nation's position as colonial followers rather than leaders. In an interview with Cecil Rhodes in March 1899 he stated the alleged dilemma clearly: "... Germany has begun her colonial enterprise very late, and was, therefore, at the disadvantage of finding all the desirable places already occupied."[65]

The German colonists included people like Carl Peters who brutalized the local population.[66]

Nonetheless, Germany did assemble an overseas empire in Africa and the Pacific Ocean (see List of former German colonies) in the last two decades of the 19th century; "the creation of Germany's colonial empire proceeded with the minimum of friction."[13] The acquisition and the expansion of colonies were accomplished in a variety of ways, but principally through mercantile domination and pretexts that were always economic. Agreements and treaties with other colonial powers or interests followed, and fee simple purchases of land or island groups.[67] Only Togoland and German Samoa became profitable and self-sufficient; the balance sheet for the colonies as a whole revealed a fiscal net loss for the empire.[68] Despite this, the leadership in Berlin committed the nation to the financial support, maintenance, development and defence of these possessions.

German colonial population

The Pennsylvania Dutch who emigrated to America in the 17th and 18th centuries were religious refugees from the Thirty Years War which devastated the German states 1616-1648 rather than colonial settlers. Germantown, Pennsylvania, was founded in 1684 and 65,000 Germans landed in Philadelphia alone between 1727 and 1775, and more at other American ports. More than 950,000 Germans immigrated to the US in the 1850s and 1,453,000 in the 1880s, but these were personal migrants, unrelated to the German Empire (created 1871) and later colonial plans. The Empire's colonies were primarily commercial and plantation regions and did not attract large numbers of German settlers.[69] The vast majority of German emigrants chose North America as their destination and not the colonies – of 1,085,124 emigrants between 1887 and 1906, 1,007,574 headed to the United States.[69] When the imperial government invited the 22,000 soldiers mobilized to subdue the Hereros to settle in German South-West Africa, and offered financial aid, only 5% accepted.[69]

The German colonial population numbered 5,125 in 1903, and about 23,500 in 1913.[70] The German pre–World War I colonial population consisted of 19,696 Germans in Africa and the Pacific colonies in 1913, including more than 3,000 police and soldiers, and 3,806 in Kiaochow (1910), of which 2,275 were navy and military staff.[70] In Africa (1913), 12,292 Germans lived in Southwest Africa, 4,107 in German East Africa and 1,643 in Cameroon.[70] In the Pacific colonies in 1913 there were 1,645 Germans.[70] After 1905 a ban on marriage was enacted forbidding mixed couples between German and native population in South-West Africa, and after 1912 in Samoa.[71]

After World War I, the military and "undesired persons" were expelled from the German protectorates. In 1934 the former colonies were inhabited by 16,774 Germans, of whom about 12,000 lived in the former Southwest African colony.[70] Once the new owners of the colonies again permitted immigration from Germany, the numbers rose in the following years above the pre–World War I total.[70]

Medicine and science

In her African and South Seas colonies, Germany established diverse biological and agricultural stations. Staff specialists and the occasional visiting university group conducted soil analyses, developed plant hybrids, experimented with fertilizers, studied vegetable pests and ran courses in agronomy for settlers and natives and performed a host of other tasks.[32] Successful German plantation operators realized the benefits of systematic scientific inquiry and instituted and maintained their own stations with their own personnel, who further engaged in exploration and documentation of the native fauna and flora.[72]

Research by bacteriologists Robert Koch and Paul Ehrlich and other scientists was funded by the imperial treasury and was freely shared with other nations. More than three million Africans were vaccinated against smallpox.[28] Medical doctors the world over benefited from pioneering work into tropical diseases and German pharmaceutical discoveries "became a standard therapy for sleeping sickness and relapsing fever. The German presence (in Africa) was vital for significant achievements in medicine and agriculture.[39]

Rebellions and genocide

Exposés followed in the print media throughout Germany of the Herero rebellions in 1904 in German South-West Africa (Namibia today) where in military interventions between 50% to 70% of the Herero population perished, known as the Herero and Namaqua Genocide. The subduing of the Maji Maji uprising in German East Africa in 1905 was prominently published. "A wave of anti-colonial feeling began to gather momentum in Germany" and resulted in large voter turnouts in the so-called "Hottentot election" for the Reichstag in 1906.[29] The conservative Bülow government barely survived, but in January 1907 the newly elected Reichstag imposed a "complete overhaul" upon the colonial service.[29]

Bernhard Dernburg, a former banker from Darmstadt, was appointed as the new secretary of the revamped colonial office. Entrenched incompetents were screened out and summarily removed from office and "not a few had to stand trial. Replacing the misfits was a new breed of efficient, humane, colonial civil servant, usually the product of Dernburg's own creation, the ... Colonial Institute at Hamburg."[30] In African protectorates, especially Togoland and German East Africa, "improbably advanced and humane administrations emerged."[28] However, Togoland saw its own share of bloodshed. The Germans used forced labor and harsh punishment to keep the Africans in line.[73] Although the lack of any true war led some in Europe to call Togoland Germany's "model colony." [73]

During the Herero genocide Eugen Fischer, a German scientist, came to the concentration camps to conduct medical experiments on race, using children of Herero people and multiracial children of Herero women and German men as test subjects.[74] Together with Theodor Mollison he also experimented upon Herero prisoners.[75] Those experiments included sterilization, injection of smallpox, typhus as well as tuberculosis.[76] The numerous cases of mixed offspring upset the German colonial administration, which was concerned with maintaining "racial purity".[76] Eugen Fischer studied 310 multiracial children, calling them "Rehoboth bastards" of "lesser racial quality".[76] Fischer also subjected them to numerous racial tests such as head and body measurements, and eye and hair examinations. In conclusion of his studies he advocated genocide of alleged "inferior races", stating that "whoever thinks thoroughly the notion of race, can not arrive at a different conclusion".[76] Fischer's (at the time considered) scientific actions and torment of the children were part of a wider history of abusing Africans for experiments, and echoed earlier actions by German anthropologists who stole skeletons and bodies from African graveyards and took them to Europe for research or sale.[76] An estimated 3000 skulls were sent to Germany for study. In October 2011, after 3 years of talks, the first skulls were due to be returned to Namibia for burial.[77] Other experiments were made by Doctor Bofinger, who injected Herero who were suffering from scurvy with various substances including arsenic and opium. Afterwards he researched the effects of these substances by performing autopsies on dead bodies.[78]

Social Darwinism

Social Darwinism is the theory, "that human groups and races are subject to the same laws of natural selection as Charles Darwin had perceived in plants and animals in nature."[79] According to numerous historians, an important ideological component of German nationalism as developed by the intellectual elite was Social Darwinism.[80] It gave an impetus to German assertiveness as a world economic and military power, aimed at competing with France and the British Empire for world power. German colonial rule in Africa 1884-1914 was an expression of nationalism and moral superiority that was justified by constructing an image of the natives as "Other". German colonization was characterized by the use of repressive violence in the name of ‘culture’ and ‘civilization’. Germany's cultural-missionary project boasted that its colonial programs were humanitarian and educational endeavors. Furthermore, the wide acceptance among intellectuals of social Darwinism justified Germany's right to acquire colonial territories as a matter of the ‘survival of the fittest’, according to historian Michael Schubert.[81][82]

Colonial German physicians and administrators tried to make a case for increasing the native population, in order to also increase their numbers of laborers. Eugene Fischer, an anthropologist at the University of Freiburg, agreed with that notion saying that they should only be supported as necessary and as they prove to be useful. Once their use is gone Europeans should, "allow free competition, which in my (Fischer's) opinion means their demise." .[83]

Colonies

| Territory | Period | Area (circa) | Current countries |

|---|---|---|---|

| German West Africa | 1896–1918 | 582,200 km²[1] | |

| German South West Africa | 1884–1918 | 835,100 km²[1] | |

| German New Guinea

(including German Samoa) |

1884–1918 | 245,861 km²[1] | |

| German East Africa | 1891–1918 | 995,000 km²[1] | |

| Total | 2,658,161 km² |

Legacy

Continuity thesis

In recent years scholars have debated the "continuity thesis" that links German colonialist brutalities to the treatment of Jews, Poles and Russians during World War II. Some historians argue that Germany's role in southwestern Africa gave rise to an emphasis on racial superiority at home, which in turn was used by the Nazis. They argue that the limited successes of German colonialism overseas led to a decision to shift the main focus of German expansionism into Central and Eastern Europe, with the Mitteleuropa plan. German colonialism, therefore, turned to the European continent.[84]

While a minority view during the Kaiserzeit, the idea developed in full swing under Erich Ludendorff and his political activity in the Baltic states, Ukraine, and Poland. Subsequently, after the defeat of Russia during World War I, Germany acquired vast territories with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and created several administrative regions like Ober Ost. Here also the German settlement would be implemented, and the whole governmental organization was developed to serve German needs while controlling the local ethnically diverse population. While the African colonies were too isolated and not suitable for mass settlement of Germans, areas in Central and Eastern Europe offered better potential for German settlement.[85] Other scholars, are skeptical and challenge the continuity thesis.[86] Additionally, however, only one former colonial officer gained an important position in the Nazi administrative hierarchy.[9]

Impact

Unlike other colonial empires such as the British, French or Spanish, Germany left very few traces of its own language, institutions or customs in its former colonies. As of today, no country outside Europe uses German as an official language, although in Namibia, German is a recognized national language and there are numerous German placenames and architectural structures in the country. A small German ethnic minority also resides in the country.

See also

Footnotes

- "Statistische Angaben zu den deutschen Kolonien". www.dhm.de (in German). Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

Sofern nicht anders vermerkt, beziehen sich alle Angaben auf das Jahr 1912.

- German South-West Africa: 835 100 km²

- Kamerun: 495 000 km²

- Togoland: 87 200

- German East Africa: 995 000

- German New Guinea: 240 000

- Marshall Islands: 400

- Kiautschou: 515

- Caroline Islands, Palau, and Mariana Islands: 2 376

- German Samoa: 2 570

- Diese deutschen Wörter kennt man noch in der Südsee, von Matthias Heine "Einst hatten die Deutschen das drittgrößte Kolonialreich[...]"

- Biskup, Thomas; Kohlrausch, Martin. "Germany 2: Colonial Empire". Credo Online. Credo Reference.

- Townsend, Mary (Jun 1938). "The German Colonies and the Third Reich". Political Science Quarterly. 53 (2): 186-206.

- (5)

- Biskup, Thomas; Kohlrausch, Martin. "Germany 2: Colonial Empire". Credo Online. Credo Reference.

- (3)

- Reichstag deputy Friedrich Kapp stated in debate in 1878 that whenever there is talk of "colonization," he would recommend to keep pocketbooks out of sight, "even if the proposal is for the acquisition of paradise." [Washausen, p. 58]

- Biskup, Thomas. "Germany: 2. Colonial empire". Credo Reference. John Wiley and Sons Ltd. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- Taylor, Bismarck. The Man and the Statesman, p. 215

- Crankshaw, Bismarck, p. 395

- Washausen, p. 115

- Crankshaw, p. 397.

- Taylor, p. 221.

- Washusen, p. 61

- {Biskup, Thomas; Kohlrausch, Martin. "Germany 2: Colonial Empire". Credo Online. Credo Reference. }

- later Kaiser-Wilhelmsland and the Bismarck Archipelago

- Washausen, p. 67-114; the West and East Africa firms

- Haupt, p. 106

- Miller, Battle for the Bundu, p. 6

- Miller, p. 10

- Washausen, p. 116

- Miller, p. 9

- once the military command was able to harness this aggressiveness through training, the German Askari forces of the Schutztruppe demonstrated that fierce spirit in their élan and war time performance [Miller, p. 28]

- Miller, p. 7

- Detzner, Hermann, (Oberleut.) Kamerun Boundary: Die nigerische Grenze von Kamerun zwischen Yola und dem Cross-fluss. M. Teuts. Schutzgeb. 26 (13): 317–338.

- Louis (1963), p. 178

- Garfield, The Meinertzhagen Mystery, p. 83

- Miller, p. 19.

- Miller, p. 20

- Churchill, Llewella P. Samoa 'uma. New York: F&S Publishing Co., 1932, p. 231

- Miller, p. 21

- Gann, L.H. & Duignan, Peter. The Rulers of German East Africa, 1884–1914. Palo Alto, California: Stanford University Press. 1977, p. 271

- Hull, Isabel V., Absolute destruction: military culture and the practices of war in Imperial Germany, pp 3ff.

- A. Dirk Moses, Empire, Colony, Genocide: Conquest, Occupation and Subaltern Resistance in World History, p. 301

- Miller, p. 23, German East Africa Usambara Railway and Central Railway; Haupt, p. 82, Togoland coast line and Hinterlandbahn; Haupt, p. 66, Kamerun northern and main line; Haupt, p. 56, map of rail lines in German South West Africa

- Miller, p. 21, school system in German East Africa; Garfield, p. 83, "hundreds of thousands of African children were in school"; Schultz-Naumann, p. 181, school system and Chinese student enrollment in Kiautschou; Davidson, p. 100, New Zealand building on the German educational infrastructure

- Miller, p. 68, German East Africa, Tanga, shelling of hospital by HMS Fox; Haupt, p. 30, photograph of Dar es Salaam hospital; Schultz-Naumann, p. 183, Tsingtao European and Chinese hospital; Schultz-Naumann, p. 169, Apia hospital wing expansion to accommodate growing Chinese labor force

- Miller, p. 22

- Haupt, p. 74

- Haupt, p. 129

- Lewthwaite, p. 149-151, in Samoa "German authorities implemented policies to draw [locals] into the stream of economic life," the colonial government enforced that native cultivable land could not be sold; Miller, p. 20, in German East Africa "new land laws sharply curtailed expropriation of tribal acreage " and "African cultivators were encouraged to grow cash crops, with technical aid from agronomists, guaranteed prices and government assistance in marketing the produce."

- Reinhard Karl Boromäus Desoye: Die k.u.k. Luftfahrtruppe - Die Entstehung, der Aufbau und die Organisation der österreichisch-ungarischen Heeresluftwaffe 1912-1918, 1999, page 76 (online)

- Louis (1967), pp. 17, 35.

- Louis (1967), p. 30.

- Louis (1967), p. 31.

- Louis (1967), p. 37.

- Louis (1967), pp. 16, 36

- Louis (1967), pp. 102–116

- Louis (1967), p. 9

- German South-West Africa was the only African colony designated as a Class C mandate, meaning that the indigenous population was judged incapable of even limited self-government and the colony to be administered under the laws of the mandatory as an integral portion of its territory, however, South Africa never annexed the country outright although Smuts did toy with the idea.

- J. A. R. Marriott, Modern England: 1885-1945 (4th ed. 1948) p. 413

- Australia in effective control, formally together with United Kingdom and New Zealand

- Louis (1967), p. 117-130

- "New Zealand goes to war: The Capture of German Samoa". nzhistory.net.nz. Retrieved 20 October 2008.

- Louis (1967), p. 132

- Louis (1967), p. 7

- General J.C. Smuts is often identified as the inventor of the idea of "mandates" [Louis (1967), p. 7]

- Louis (1967), p. 6

- Louis (1967), p. 157

- Louis (1963), p. 233

- Louis (1967), p. 159

- Louis (1967), p. 160

- Washausen, p. 162

- Louis (1963), Ruanda-Urundi, p. 163

- German Colonialism: A Short History, Sebastian Conrad, page 146, Cambridge University Press, 2012

- As an example, in February 1899 a treaty was signed by which Spain sold the Caroline and Mariana Islands and Palau for 17 million gold mark to Germany

- Haupt, Deutschlands Schutzgebiete, p. 85

- Henderson, William Otto (1962). Studies in German colonial history (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 0-7146-1674-5. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Henderson, William Otto (1962). Studies in German colonial history (2 ed.). Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 0-7146-1674-5. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Conrad, Sebastian (2012) German Colonialism: A Short History. Cambridge University Press, p. 158

- Spoehr, Florence. (1963) White Falcon. The House of Godeffroy and its Commercial and Scientific Role in the Pacific. Palo Alto, California: Pacific Books, p. 51-101

- Lauman, Dennis (2003). "A Historiography of German Togoland, or the Rise and Fall of a "Model Colony". History In Africa. 30: 195-211.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. (2001) When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 12

- Cooper, Allan D. (2008) The Geography of Genocide. University Press of America, p. 153

- Hitler's Black Victims: The Historical Experiences of European Blacks, Africans and African Americans During the Nazi Era (Crosscurrents in African American History) by Clarence Lusane, page 50-51 Routledge 2002

- "Germans return skulls to Namibia. On Friday, Germany will return the first 20 of an estimated 300 skulls of indigenous Namibians butchered a century ago during an anti-colonial uprising in what was then called South West Africa". Times LIVE. 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- Erichsen, Casper and David Olusoga (2010) The Kaiser's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. Faber and Faber, p. 225

- Encyclopedia Britannica. "Social Darwinism". Encyclopedia Britannica. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Richard Weikart, "The Origins of Social Darwinism in Germany, 1859-1895." Journal of the History of Ideas 54.3 (1993): 469-488 in JSTOR.

- Michael Schubert, "The ‘German nation’ and the ‘black Other’: social Darwinism and the cultural mission in German colonial discourse," Patterns of Prejudice (2011) 45#5 pp 399-416.

- Felicity Rash, The Discourse Strategies of Imperialist Writing: The German Colonial Idea and Africa, 1848-1945 (Routledge, 2016).

- Weikart, Richard (7 May 2003). "Progress through Racial Extermination: Social Darwinism, Eugenics, and Pacifism in Germany, 1860-1918". German Studies Review. 26: 273–294.

- Germany subsequently tried to turn Europe into its colonial possession by practicing a migrations form of colonialism that was reworked into the ideology of Lebensraum(...)Aime Cesaire pointed out that fascism was a form of colonialism brought home to Europe Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction Robert Young Published 2001 Blackwell Publishing page 2

- Helmut Bley, Continuities and German Colonialism: Colonial Experience and Metropolitan Developments Historisches Seminar, Universität Hannover 2004

- Volker Langbehn and Mohammad SalamaRace, eds. the Holocaust, and Postwar Germany (Columbia U.P., 2011)

Sources and references

- Achleitner, Arthur; Johannes Biernatzki (1902). Deutschland und seine Kolonieen; Wanderungen durch das Reich und seine überseeischen Besitzungen, unter Mitwirkung von Arthur Achleitner, Johannes Biernatzki [etc.]. Berlin, Germany: H. Hilger.

- Westermann, Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte (in German)

- WorldStatesmen.org

Bibliography

- Berghahn, Volker Rolf. "German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler" German Studies Review 40#1 (2017) pp. 147–162 Online

- Boahen, A. Adu, ed. (1985). Africa Under Colonial Domination, 1880–1935. Berkeley: U of California Press]].CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link) ISBN 978-0-520-06702-8 (1990 Abridged edition).

- Carroll, E. Malcolm. Germany and the great powers, 1866-1914: A study in public opinion and foreign policy (1938) online; online at Questia also online review

- Churchill, William. "Germany's Lost Pacific Empire" Geographical Review 10.2 (1920): 84–90. online

- Crankshaw, Edward (1981). Bismarck. New York: The Viking Press. ISBN 0-14-006344-7.

- Davidson, J. W. (1967). Samoa mo Samoa, the Emergence of the Independent State of Western Samoa. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

- Eley, Geoff, and Bradley Naranch, eds. German Colonialism in a Global Age (Duke UP, 2014).

- Gann, L., and Peter Duignan. The Rulers of German Africa, 1884–1914 (1977) focuses on political and economic history

- Garfield, Brian (2007). The Meinertzhagen Mystery. Washington, DC: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-59797-041-7.

- Giordani, Paolo (1916). The German colonial empire, its beginning and ending. London: G. Bell.

- Henderson, W. O. "The German Colonial Empire, 1884–1918" History 20#78 (1935), pp. 151–158 Online, historiography

- Lahti, Janne. "German Colonialism and the Age of Global Empires." Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 17.1 (2016). historiography; excerpt

- Lewthwaite, Gordon R. (1962). James W. Fox; Kenneth B. Cumberland (eds.). Life, Land and Agriculture to Mid-Century in Western Samoa. Christchurch, New Zealand: Whitcomb & Tombs Ltd.

- Louis, Wm. Roger (1967). Great Britain and Germany's Lost Colonies 1914–1919. Clarendon Press.

- Louis, Wm. Roger (1963). Ruanda-Urundi 1884–1919. Clarendon Press.

- Miller, Charles (1974). Battle for the Bundu. The First World War in East Africa. Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-584930-1.

- Olivier, David H. German Naval Strategy, 1856–1888: Forerunners to Tirpitz (Routledge, 2004).

- Poddar, Prem, and Lars Jensen, eds., A historical companion to postcolonial literatures: Continental Europe and Its Empires (Edinburgh UP, 2008), "Germany and its colonies" pp 198–261. excerpt also entire text online

- Reimann-Dawe, Tracey. "The British Other on African soil: the rise of nationalism in colonial German travel writing on Africa," Patterns of Prejudice (2011) 45#5 pp 417–433, the perceived hostile force was Britain, not the natives

- Smith, W.D. (1974). "The Ideology of German Colonialism, 1840–1906". Journal of Modern History. 46 (1974): 641–663. doi:10.1086/241266.

- Steinmetz, George (2007). "The Devil's Handwriting: Precoloniality and the German Colonial State in Qingdao, Samoa, and Southwest Africa". Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226772438. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Stoecker, Helmut, ed. (1987). German Imperialism in Africa: From the Beginnings Until the Second World War. Translated by Bernd Zöllner. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International. ISBN 978-0-391-03383-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Strandmann, Hartmut Pogge von. "Domestic Origins of Germany's Colonial Expansion under Bismarck" Past & Present (1969) 42:140–159 online

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1967). Bismarck, The Man and the Statesman. New York: Random House, Inc.

- Townsend, Mary Evelyn. The rise and fall of Germany's colonial empire, 1884-1918 (1930).

- Wehler, Hans-Ulrich "Bismarck's Imperialism 1862–1890," Past & Present, (1970) 48: 119–55 online

- Wesseling, H.L. (1996). Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880-1914. Translated by Arnold J. Pomerans. Westport, CT: Preager. ISBN 978-0-275-95137-5. ISBN 978-0-275-95138-2 (paperback).

In German

- Detzner, Hermann, (Oberleut.) Kamerun Boundary: Die nigerische Grenze von Kamerun zwischen Yola und dem Cross-fluss. M. Teuts. Schutzgeb. 26 (13): 317–338.

- Haupt, Werner (1984). Deutschlands Schutzgebiete in Übersee 1884–1918. [Germany’s Overseas Protectorates 1884–1918]. Friedberg: Podzun-Pallas Verlag. ISBN 3-7909-0204-7.

- Nagl, Dominik (2007). Grenzfälle – Staatsangehörigkeit, Rassismus und nationale Identität unter deutscher Kolonialherrschaft. Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang Verlag. ISBN 978-3-631-56458-5.

- Perraudin, Michael, and Jürgen Zimmerer, eds. German Colonialism and National Identity (2010) focuses on cultural impact in Africa and Germany.

- Schultz-Naumann, Joachim (1985). Unter Kaisers Flagge, Deutschlands Schutzgebiete im Pazifik und in China einst und heute. [Under the Kaiser’s flag, Germany’s Protectorates in the Pacific and in China then and today]. Munich: Universitas Verlag.

- Schaper, Ulrike (2012). Koloniale Verhandlungen. Gerichtsbarkeit, Verwaltung und Herrschaft in Kamerun 1884-1916. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag. ISBN 3-593-39639-4.

- Washausen, Helmut (1968). Hamburg und die Kolonialpolitik des Deutschen Reiches. [Hamburg and Colonial Politics of the German Empire]. Hamburg: Hans Christians Verlag.

- Karl Waldeck: "Gut und Blut für unsern Kaiser", Windhoek 2010, ISBN 978-99945-71-55-0

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 1, 2. Auflage Windhoek 2012, ISBN 978-99916-872-1-6

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 2, "Naulila", Windhoek 2012, ISBN 978-99916-872-3-0

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 3, "Kämpfe im Süden", Windhoek 2014, ISBN 978-99916-872-8-5

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 4, "Der Süden ist verloren", Windhoek 2015, ISBN

- Historicus Africanus: "Der 1. Weltkrieg in Deutsch-Südwestafrika 1914/15", Band 5, "Aufgabe der Küste", Windhoek 2016, ISBN 978-99916-909-4-0

In French

- Gemeaux (de), Christine,(dir., présentation et conclusion): "Empires et colonies. L'Allemagne du Saint-Empire au deuil post-colonial", Clermont-Ferrand,PUBP, coll. Politiques et Identités, 2010, ISBN 978-2-84516-436-9.

External links

- Deutsche-Schutzgebiete.de ("German Protectorates") (in German)

-en.png)