Great Siege of Gibraltar

The Great Siege of Gibraltar was an unsuccessful attempt by Spain and France to capture Gibraltar from the British during the American Revolutionary War.

The British garrison under George Augustus Eliott were blockaded from June 1779 to February 1783[20], initially by the Spanish alone, led by Martín Álvarez de Sotomayor. The blockade proved to be a failure because two relief convoys entered unmolested—the first under Admiral George Rodney in 1780 and the second under Admiral George Darby in 1781—despite the presence of the Spanish fleets. The same year, a major assault was planned by the Spanish, but the Gibraltar garrison sortied in November and destroyed much of the forward batteries. With the siege going nowhere and constant Spanish failures, the besiegers were reinforced by French forces under de Crillon, who took over command in early 1782. After a lull in the siege, during which the Franco-Spanish besiegers gathered more guns, ships and troops, a "Grand Assault" was launched on 18 September 1782. This involved huge numbers — 60,000 men, 49 ships of the line and ten specially designed, newly invented floating batteries — against the 5,000 defenders. The assault proved to be a disastrous and humiliating failure, resulting in heavy losses for the Bourbon attackers.

The siege then settled down again into a Franco-Spanish blockade, but the final sign of defeat for the allies came when a crucial British relief convoy under Admiral Richard Howe slipped through the blockading fleet and arrived at the garrison in October 1782. The siege was finally lifted on 7 February 1783 and resulted in a decisive victory for the British, being a vital factor in the Peace of Paris, which had been negotiated towards the end of the siege.[21][22]

This was the largest action fought during the war in terms of numbers, particularly the "Grand Assault". At three years and seven months, it is the longest siege endured by the British Armed Forces and one of the longest sieges in history.[23]

Background

In 1738 a dispute between Spain and Great Britain arose over commerce between Europe and the Americas. Initially, both sides intended to sign an agreement at the Spanish Royal Palace of El Pardo, but in January of the following year, the British Parliament rejected the advice of Foreign Minister Robert Walpole, a supporter of the agreement with Spain.[24] A short time later, the War of Jenkins' Ear began, and both countries declared war on 23 October 1739, each side drawing up plans to establish trenches near Gibraltar.[25] Seeing these first movements, Britain ordered Admiral Vernon to sail from Portobello and strengthen the squadron of Admiral Haddock who was already stationed in the Bay of Gibraltar.[26]

The passage of years failed to break the hostilities in the region. Then on 9 July 1746, King Philip V of Spain died in Madrid. His successor, Ferdinand VI, soon began negotiations with Britain on trade. The British Parliament was amenable to such negotiations, and even looked favourably upon lifting the British embargo on Spain and possibly ceding Gibraltar. The neutrality adopted by Ferdinand VI quickly ended with his death in 1759. The new king, Charles III, was less willing to negotiate with Great Britain. Instead, he signed a Family Compact with Louis XV of France on 15 August 1761. At that time France was at war with Britain, so Britain responded by declaring war on Spain and capturing the Spanish colonial capitals of Manila and Havana. Two years later, after cessation of hostilities, Spain recovered Manila and Havana in exchange for Spanish holdings in Florida as part of the 1763 Treaty of Paris.[27]

In the years of peace that followed both France and Spain hoped for an opportunity to launch a war against Britain on more favourable terms and recover their lost colonial possessions. Following the outbreak of the American War of Independence, both states supplied funding and arms to the American rebels, and drew up a strategy to intervene on the American side and defeat Britain.[28]

In October 1778 France entered the war and on 12 April 1779, both France and Spain signed the Treaty of Aranjuez wherein they agreed to aid one another in recovering lost territory from Britain.[29] France and Spain sought to secure Gibraltar, which was a key link in Britain's control of the Mediterranean Sea, and expected its capture to be relatively quick—a precursor to a Franco-Spanish invasion of Great Britain.[30]

Opposing forces

| Commanders |

|---|

|

The Spanish blockade was to be directed by Martín Álvarez de Sotomayor. Spanish ground forces were composed of 16 infantry battalions, which included the Royal Guards and the Walloon Guards, along with artillery and 12 squadrons of cavalry. This yielded a total of about 14,000 men in all.[31] The artillery was commanded by Rudesindo Tilly, while the cavalry and the French dragoons were headed by the Marquis of Arellano. Antonio Barceló commanded the maritime forces responsible for blockading the bay. He established his base in Algeciras, with a fleet of several xebecs and gunboats.[9] A fleet of 11 ships of the line and two frigates were placed in the Gulf of Cadiz under the command of Luis de Córdova y Córdova to block the passage of British reinforcements.[32]

The British garrison in 1778 consisted of 5,382 soldiers; General Eliott was the Governor-General. All the defences were strengthened; the main physical task facing Eliott was an extensive building programme of new fortifications for Gibraltar, as set out in a report by a commission that had examined the state of the Rock's defences in the early 1770s. The most prominent new work was the King's Bastion designed by Sir William Green and built by the Soldier Artificer Company on the main waterfront of the town in Gibraltar.[33] The King's Bastion comprised a stone battery holding 26 heavy guns and mortars, with barracks and casemates to house a full battalion of foot. The Grand Battery protected the Land Port Gate, the main entrance to Gibraltar from the isthmus connecting to the Spanish mainland. Other fortifications and batteries crowded along the town's waterfront and on the Rock.[34]

Eliott began a programme of increasing the number of guns deployed in the batteries and fortifications, which initially stood at 412, many of them inoperable. Many of the infantry assisted the artillery in serving the guns. The garrison included three battalions of Hanoverian and around 80 Corsican troops. Eliott also formed a corps of sharpshooters. The navy had only a token force; most of the sailors and marines were used on shore, but one ship of the line, HMS Panther, was being used as a hulk and floating battery. The frigate HMS Enterprise and 12 gunboats were also present.[35] Elliott's determined handling of the preparations inspired all the troops under him with the greatest confidence. The British had anticipated an attack for some time, and many ships had sailed to reinforce and supply Gibraltar.[36] Britain stepped up preparations after France entered the conflict in 1778, although the French were initially more concerned with sending forces to America, and it was not until Spain joined the war that the long-expected siege commenced.[37]

Siege

On 16 June 1779, the Spanish issued what was in effect a declaration of war against Great Britain, and a blockade immediately commenced. On 6 July 1779, an engagement took place between the British ships and Spanish vessels bringing supplies to the Spanish troops on shore. Several Spanish vessels were taken and the hostilities began. The combined Spanish and French fleets blockaded Gibraltar from the sea, while on the land side an enormous army constructed forts, redoubts, entrenchments, and batteries from which to attack.[34]

As the winter of 1779 came, provisions for the garrison soon became scarce. Bread was almost impossible to obtain and was not permitted to be issued except to the sick and children. Salt meat and biscuits soon became a major part of the rations, with an occasional issue of four ounces of rice each day. Fuel was exhausted, and fires were made only with difficulty, using the salt-encrusted timbers of old ships broken up in the harbour for the purpose. As a result, a violent outbreak of scurvy occurred among the troops, owing to the lack of vegetables and medicines.[38] Eliott appealed to London for relief, but as the winter wore on rations were reduced further. Despite this, the garrison's morale remained high, and the troops continued to take their turns at various posts of duty. They had also repulsed several small testing assaults made by the Spanish and had great faith that they would receive supplies by sea, and so they endured the cold and hunger.[39]

The Spanish were forced to commit a greater number of troops and ships to the siege, postponing the planned Invasion of England, owing to this and the cancellation of the Armada of 1779.[40]

First naval relief

In December 1779, a large convoy sailed from England to Gibraltar, escorted by 21 ships of the line under the command of Admiral George Rodney. On their way, they encountered and captured a Spanish convoy off Cape Finisterre on 8 January 1780. They planned to provision the Gibraltar garrison further with the goods they had captured.[41] The Spanish soon learned of the convoy and sent a fleet under Juan de Langara to intercept it, but underestimated the escort's strength, and Langara's ships soon had to flee. Rodney caught up with and defeated the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Cape St. Vincent, taking five ships of the line and additional supplies.[42] The fleet easily penetrated the Spanish blockade and reached Gibraltar on 25 January 1780, bringing reinforcements of 1,052 men of the 73rd Highland regiment of foot under George Mackenzie and an abundance of supplies, including the captured Spanish goods.[43] This greatly heartened the garrison, but as soon as Rodney's fleet left, the siege resumed.[44]

The British defenders resisted every attempt to capture Gibraltar by assault. While the two sides unceasingly exchanged shot and shell, by the end of the summer, provisions again began to run low, and scurvy began to reappear, reducing the effective strength of the garrison. Through the use of small, fast-sailing ships that ran the blockade, they were able to keep in communication with the British forces besieged on Minorca, but that force was also low on supplies.[45]

On 7 June 1780 the two largest ships of Gibraltar, HMS Panther and HMS Enterprise, were targeted within Gibraltar's harbour by Spanish fireships.[46] Warning shots from Enterprise alerted the garrison and soon an intense bombardment slowed the fire ships. A few were sunk but the others carried on; the Spanish fleet waited just outside the harbour for any British ships trying to escape, so seamen from Panther and Enterprise set out in longboats, intercepted the fire ships, and towed them off course.[47]

Second naval relief

Throughout the second winter the garrison faced foes, elements, disease, and starvation. By March the situation was serious: the garrison and civilians were on weekly rations and in need of a large supply. For the Spanish the blockade was working, with the few small ships that slipped past the blockade carrying insufficient supplies.[48]

On 12 April 1781 Vice Admiral George Darby's squadron of 29 ships of the line escorting 100 store ships from England entered the bay, despite the Spanish fleet.[49] The Spanish, frustrated by this failure, for the first time in the siege opened up a terrific barrage while the stores were unloaded. Although they caused great damage to the town, the South Mole where the ships unloaded their stores was out of their reach. The civilian population of about 1,000 sailed with Darby for England on 21 April, leaving the garrison with fewer mouths to feed and allowing them to operate more freely. Again the fleet left without hindrance during the night and slipped past the blockading Spanish fleet. Provisions for the garrison were now plentiful, including black powder, guns and ammunition as well as food and other supplies.[50]

The French and Spanish thus found it impossible to starve the garrison out. They therefore resolved to make further attacks by land and sea and assembled a large army and fleet to carry this out. In addition, the Spanish built a succession of new batteries across the isthmus:[51] soon there were four of them each containing around fourteen guns. There were also the preexisting San Carlos, San Felipe, and Santa Barbara batteries, each containing around 24 to 27 guns.

On 9 June, the British gunners hit a major Spanish magazine, which exploded. The main explosion was followed by a host of minor ones, as expense magazines, subsidiary stores and shells blew up. The Spanish lines were in pandemonium as the troops struggled to put out the numerous fires that started in their camp. Eventually order was restored and the fires failed to halt the Spanish effort of battery building. By late 1781 there were around fifty mortars, bringing the besiegers' total to 114 guns, ranging from heavy 24 pounders to twelve-inch mortars.[49]

Sortie

By November, just as hunger began to start again for the garrison, they received word from some Spanish deserters that a massive assault was planned. General Eliott decided that a night sortie to attack the Spanish and French on the eve of their assault would be the perfect move.[52]

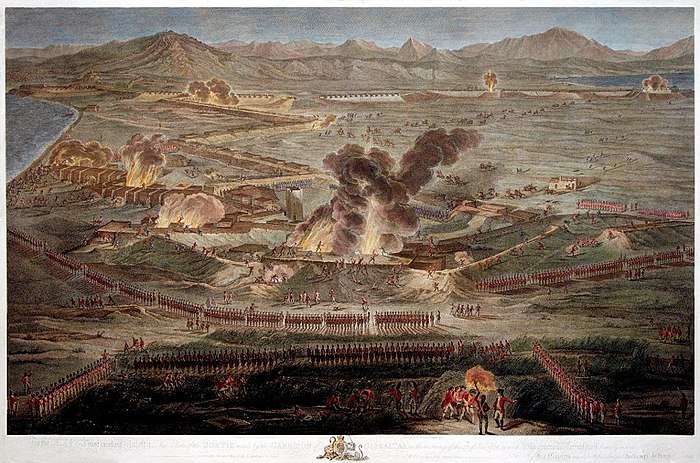

On 27 November 1781, the night before they were to launch the grand attack, the British made their surprise sortie. In all 2,435 soldiers with 99 officers were involved, organised into three columns of around 700–800 men each——they included engineers and pioneers who were armed with axes and firing equipment.[52] At around 2:00 they marched towards the besiegers' lines. The right column came across the Spanish sentries at the end of the parallel, charged, and stormed the lines, bayoneting the Spanish defenders. While the rest of the defenders retreated, the eastern flank of the Spanish advanced works was taken and consolidated.[46] One detachment of the right column, a group of Hanoverians, got lost in the dark, mistook its target and found themselves at the base of the huge San Carlos mortar battery.[53] Having realised their mistake, they decided to attack the position, and after some heavy fighting the position was taken. This battery had been the intended target of the centre column, which came up and reinforced the position and prepared for a Spanish counterattack. Meanwhile the left column struck along the seashore meeting light resistance; the flank companies of the 73rd Highlanders charged ahead and stormed the San Pascual and the San Martin batteries and took the trenches, putting the Spanish to flight.[13]

Elliot decided to come out and view the victory, much to the surprise of the British officers. A badly wounded Spanish artillery officer José de Barboza refused to be moved —– Elliot tried to persuade him but he asked to be "left alone and perish amid the ruin of my post". This would be an inspiration for a painting by John Trumbull.[54] With all the Spanish forward positions secured, the British set upon the destruction of provisions, ammunition, weapons, defensive structures, taking booty and spiking the guns. They set fire to the ammunition and the siege works were engulfed in flames. Soon after, Spanish cavalry were observed coming up; they faced a Hanoverian battalion but did not charge. The Spanish under Alvarez had no plans and were neither expecting nor prepared for a British sortie.[55]

With the objective completed, the British withdrew back inside their fortifications. The total British and Hanoverian casualties in the sortie were two killed and 25 wounded. Spanish losses were over 100 men, which included thirty prisoners; a number of these were blue-coated Walloon soldiers of the Walloon Guards.[56] The British did damage to the extent of two million pounds to the besiegers: fourteen months of work by the Spanish and a considerable quantity of ammunition had been destroyed. British troops and pioneers spiked ten thirteen-inch mortars and eighteen twenty-six-pounder guns in the Spanish siege works. In addition the platforms and beds on which the guns were based were also destroyed. As the British returned after their victorious sortie the garrison watched in amazement as huge explosions from the ammunition ripped through the Spanish lines and destroyed what was left of them.[57]

This sortie postponed the great Spanish assault for several months. In that time the British began building an extensive tunnel network through the Rock of Gibraltar. The work was carried out by hand aided by gunpowder blasts, which was dangerous. It took thirteen men five weeks to dig a tunnel with a length of 82 feet (25 m). Embrasures were blasted overlooking the Spanish lines. Additionally, a new type of cannon mount was invented that allowed a cannon to fire at a downward angle. The new depressing gun-carriage was devised by George Koehler which allowed guns to be fired down a slope.[58] This was demonstrated on 15 February 1782 at Princess Royal's Battery.[59] This new carriage enabled the defending guns to take advantage of the height of the Rock of Gibraltar: they could strike out far, but also be angled downward to fire on approaching attackers.[60]

At the beginning of March news of the surrender of the Minorca garrison was received and lowered morale for the besieged. The Spanish and French at Gibraltar would soon be reinforced by the victors of Minorca.[61] Life however in Gibraltar was able to carry on with relief from merchants who ran the Spanish blockade. British ships arrived unmolested to bring in reinforcements, taking away the sick, prisoners and civilians. Portuguese vessels with lemons, wine and vegetables helped the garrison, and gave valuable intelligence on the Spanish lines and the heavy casualties suffered from the British guns. News of HMS Success's defeat of a Spanish frigate Santa Catalina bought much rejoicing to the rock when she entered.[62]

Arrival of the French

Soon after the surrender of Minorca, French forces from that siege arrived to help the Spanish at Gibraltar. In particular, French engineers and pioneers were brought in, and Louis des Balbes de Berton de Crillon, duc de Mahon took over from Álvarez de Sotomayor as commander of the besiegers, with the final say in operations. Álvarez de Sotomayor was effectively demoted to take command of the Spanish contingent. Both the Spanish and the French hoped for more imaginative concepts and arrangements to bring about victory. French ships joined de Córdova's already powerful Spanish navy to strengthen the blockade. During this time it was decided to construct the special floating batteries, and soon the British garrison observed hulks being brought into the Bay of Gibraltar.[63] The American diplomat Louis Littlepage acted as a volunteer aide to de Crillon during the siege and made sketches of the operations.[64]

With the arrival of more troops and ships, guns and mortars were also delivered to the Spanish siege lines, which were creeping forward and soon neared completion. A new Spanish battery, the Mahon, was erected in quick time, despite being hit many times by the British siege guns, which caused severe losses. Elliot though did not strike once it had been finished in April 1782.[65]

A lull in the siege then occurred, with each side not knowing when the other would bombard; this went on through the summer. On 11 June, a Spanish shell exploded inside the magazine of Princess Anne's Battery further up the Rock, causing a massive explosion that blew the flank of the battery into the Prince's Lines, killing 14 soldiers.[66]

Destruction of Spanish batteries

In early September the Spanish advanced their lines further, right up to the British siege guns' effective range. Elliot suggested to his artillery general Boyd to bombard the lines with red-hot shot and grapeshot, which had been used to great effect against Spanish gunboats daring to come close to make an attack. These "hot potatoes", as they were nicknamed, were pre-heated to furnace temperatures before being fired at the dry wooden defences.[67]

At 7 am on 8 September 1782 the bombardment commenced, concentrating mainly on the western parallel of the Spanish siege works. Supporting the heavy guns were the field artillery and other types of British guns. Within a few hours of intense bombardment the results became apparent and soon exceeded the garrison's expectations.[68] The Mahon battery along with conjoining works were set on fire.[69] The other batteries San Carlos and San Martin were heavily damaged and had to be partly dismantled by French and Spanish pioneers.[70]

The bombardment was a huge success and had inflicted great damage: Spanish and French casualties numbered at least 280. The red-hot shot had proved a success; furnaces and grates were therefore installed right next to the batteries.[67]

The Grand Assault

| Battery | Men | Guns in use | Guns in reserve | Captain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pastora | 760 | 21 | 10 | Buenaventura Moreno |

| Talla Piedra | 760 | 21 | 10 | Príncipe Nassau |

| Paula Primera | 760 | 21 | 10 | Cayetano de Lángara |

| Rosario | 700 | 19 | 10 | Francisco Muñoz |

| San Cristóbal | 650 | 18 | 10 | Federico Gravina |

| Paula Segunda | 340 | 9 | 4 | Pablo de Cózar |

| Santa Ana | 300 | 7 | 4 | José Goicoechea |

| San Juan | 340 | 9 | 4 | José Angeler |

| Príncipe Carlos | 400 | 11 | 4 | Antonio Basurto |

| Dolores | 250 | 6 | 4 | Pedro Sánchez |

| Total (10 ships) | 5,260 | 142 | 70 | |

For the allies it was becoming clear that the recent blockades had been a complete failure and that an attack by land would be impossible. Ideas were put forward to break the siege once and for all. The plan was proposed that a squadron of battery ships should take on the British land-based batteries and pound them into submission by numbers and weight of shots fired, before a storming party attacked from the siege works on the Isthmus and further troops were put ashore from the waiting Spanish fleet.[72] The French engineer Jean Le Michaud d'Arçon invented and designed the floating batteries—‘unsinkable’ and ‘unburnable’—intended to attack from the sea in tandem with other batteries bombarding the British from land. The floating batteries would have strong thick wooden armour—1-metre-wide (3 ft) timbers packed with layers of wet sand and with water pumped over them to avoid fire breaking out.[73] In addition old cables would also deaden the fall of British shot and, as ballast, would counterbalance the guns' weight. Guns were to be fired from one side only; the starboard battery was removed completely and the port battery heavily augmented with timber and sand infill. The ten floating batteries would be supported by ships of the line and bomb ships, which would try to draw away and split up the British fire. Five batteries each with two rows of guns together with five smaller batteries each with a single row would provide a total of 150 guns.[72] The Spanish enthusiastically received the proposal. D'Arcon sailed close to shore under enemy fire in a skiff to get more accurate intelligence.[74]

On 13 September 1782 the Bourbon allies launched their great attack; 5,260 fighting men, both French and Spanish, aboard ten of the newly engineered 'floating batteries' with 138[75] to 212 heavy guns, and with Don Buenaventura Moreno commanding.[76] Also in support were the combined Spanish and French fleet, which consisted of 49 ships of the line, 40 Spanish gunboats and 20 bomb-vessels, manned by a total of 30,000 sailors and marines[74] under the command of Spanish Admiral Luis de Córdova.[77][78] They were supported by 86 land guns[78] and 35,000 Spanish and French troops (7,000[79]–8,000[10] French) on land, intending to assault the fortifications once they had been demolished.[80] An 'army' of over 80,000 spectators thronged the adjacent hills on the Spanish side, expecting to see the fortress beaten to powder and 'the British flag trailed in the dust'. Among them were the highest families in the land, including the Comte D'Artois.[81]

The batteries slowly moved forward along the bay; one by one the 138 guns opened fire, but soon events did not go according to plan. The alignments were not correct; the two lead ships Pastora and the Tala Piedra moved further ahead than they should have.[82] When they opened fire on their main target, the King's Battery, the British guns replied but the cannonballs were observed to bounce off their hulls. Eventually the Spanish junks were anchored on the sandbanks near the Mole but were too spread out to create any significant damage to the British walls.[83]

Meanwhile, after weeks of preparatory artillery fire, the 200 heavy-calibre Spanish and French guns opened up on the land side from the North directed onto the fortifications. This caused some casualties and damage, but by noon the artificers had heated up red-hot shot. Once the shot were ready, Elliot ordered them to be fired. Heated shot was actually quicker to load since it did not need to be rammed. At first the heated shot made no difference, as many were doused on board the floating batteries.[74]

Although the batteries had anchored, a number had soon grounded and began to suffer damage to the rigging and masts. The King's Bastion blasted away at the closest ships, the Pastora and the Talla Peidra, and soon the British guns began to have effect. Smoke was spotted coming from Talla Piedra, already severely damaged with its rigging in tatters.[82] Panic ensued since no vessel could come and support her; nor was there any way of the ship escaping. Meanwhile the Pastora under the Prince de Nassau began to emit a huge amount of smoke. Despite efforts to find the cause, the sailors on board were fighting a losing battle.[84] To make matters worse, the Spanish land guns had ceased firing. It soon became apparent to de Crillon that the Spanish army had run out of powder and were already low on shot. By nightfall it was clear that the assault had failed, but worse was to come because the fire on the two batteries was out of control. To add to de Crillon's frustration, de Córdova's ships of the line failed to move in support, and neither did Barcelo's vessels.[74] De Crillon, acknowledging defeat and not wishing to upset the Spanish by issuing demands, soon ordered the floating batteries to be scuttled and the crews rescued. Rockets were sent up from the batteries as distress signals.[84]

Destruction of the floating batteries

During this operation, Roger Curtis, the British naval commander, seeing the attacking force in great danger, warned Elliot about the huge potential death toll and that something must be done. Elliot agreed and had the fleet of twelve gunboats under Curtis set out with 250 men. They headed towards the Spanish gunboats, firing as they advanced. The Spanish precipitated a quick retreat.[85]

Curtis' gunboats reached the batteries and one by one took them; but this soon turned into a rescue effort when they realised from prisoners that many men were still on board with the scuttling now taking place.[86] British marines then stormed the Pastora, taking the men on board as prisoners and eventually pulled them off the doomed ship, having also seized the Spanish Royal Standard. As this was going on, the flames that had engulfed Talla Piedra soon reached the magazine. The ensuing explosion was tremendous, with a sound that reverberated around the bay and a huge mushroom cloud of smoke and debris that rose up in the air.[87] Many were killed on board but the British had few casualties. The Spanish, now in panic, all reached for the British boats by jumping in the water. Soon the Pastora, engulfed in a mass of flames, followed the fate of the Talla Piedra: another huge explosion ensued. This time many in the water were killed outright; a British boat was sunk and the coxswain of Curtis's boat was killed when hit by debris.[74]

Curtis realised that it was unsafe to be near the flaming batteries and soon withdrew men from two more floating batteries engulfed in flame, then finally ordered a withdrawal.[74] The rescue operation was hindered further when Spanish batteries opened fire after receiving more powder and shot. Many more men drowned or were burned in the ensuing inferno; others were hit by their own artillery. The Spanish ceased fire only when the mistake was realised, but it was too late.[86] The rest of the Spanish batteries blew up in similar horrific style; the explosions lofted huge mushroom clouds that rose nearly 1,000 feet in the air.[73] Some men were still on board and those that had jumped overboard often drowned as the vast majority couldn't swim. By the early hours of the morning only two floating batteries remained. A Spanish Felucca tried to set one on fire but was driven off by British guns. The two were promptly set alight by them and were finished in the same way as the others by the afternoon.[88]

By 4 am, all the floating batteries had been sunk, leaving the Gibraltar waterfront a mass of debris and bodies from the wrecked Spanish ships. During the Grand Assault 40,000 rounds had been fired. Casualties in just 12 hours were heavy: 719 men on board the ships (many of whom drowned) were casualties.[89]

Curtis had rescued a further 357 officers and men, who thus became prisoners, while in the siege lines more casualties brought up the allied total to 1,473 men for the Grand Assault, with all ten floating batteries destroyed.[87] The engagement was the fiercest battle of the war and many bodies washed up ashore.[73] The British lost 15 killed and 68 men were wounded, nearly half of them from the Royal Artillery. A British sailor found and took Pastora's large Spanish colour, which had flown from the stern, and presented it to Elliot.[90]

One of the survivors who had been on a floating battery that had blown up was the American Louis Littlepage. He was saved and managed to get back to the Spanish fleet.[64]

For Elliot and the garrison it was a great victory and for the allies it was a brutal defeat, with their plans and hopes were in tatters. De Córdova was heavily criticised for not coming to help the batteries, while d'Arcon and de Crillon threw accusations and recriminations at each other.[91] In Spain the news was met with consternation and despair. The huge crowds that had been promised a crushing victory left the area chagrined.[92]

On 14 September 1782, another assault by the allies by land was planned. The Spanish army formed up behind the batteries at the northern end of the Isthmus. At the same time, the Spanish ships moved across the bay, packed with more troops. However, de Crillon cancelled the assault, judging that losses would have been huge.[93]

Gibraltar remained under siege, but Spanish bombardments decreased to about 200 rounds a day as both sides knew of the impending peace treaty, for which the siege of Gibraltar would be a major factor.[94]

Final actions

From 20 September, reports of the great French and Spanish assault on Gibraltar began to reach Paris; all were negative. By 27 September it was clear that the operation, involving more troops than had ever been in service at one time on the entire North American continent, had been a horrific disaster.[82] In Madrid news of the failure was received with dismay; the King was in mute despair as he read the intelligence reports at the Palace of San Ildefonso.[92] The French had done all they could to help the Spanish achieve their essential war aim, and began serious discussions on alternative exit strategies, urging Spain to offer Britain some very large concessions in return for Gibraltar.[95]

In Britain the Admiralty considered plans for a major relief of Gibraltar, opting to send a larger but slower fleet, rather than a smaller, faster one. This was key to the outcome of the siege.[96] Admiral Richard Howe's orders were to deliver the supplies to Gibraltar and then to return to England. The fleet—composed of 35 ships of the line, a large convoy of transports destined for Gibraltar, and additional convoys destined for the East and West Indies—left Spithead on 11 September. Bad weather and contrary winds however meant that the British fleet did not arrive at Cape St. Vincent until 9 October.[97]

Capture of the San Miguel

On 10 October a storm wreaked havoc on the allied fleet: one ship of the line was driven aground, and another was swept through the Straits of Gibraltar into the Mediterranean.[98] One other, the Spanish ship of the line San Miguel, of seventy two guns, under the command of Don Juan Moreno, lost its mizzen mast in the storm.[99] It was driven helplessly into Gibraltar by the storm. Cannon fire from the King's Bastion was fired at the vessel, some of which penetrated and caused damage and casualties. The San Miguel then tried with great difficulty to get out of danger but was soon grounded. Gunboats from the garrison quickly captured her. Moreno agreed to surrender to avoid any further bloodshed, being too close to the guns of Gibraltar. A total of 634 Spanish sailors, marines and dismounted dragoons were captured.[100] An attempt by the Spanish and French on 17 December to bombard the San Miguel with mortars failed and caused only minimal damage. By this time the powder magazine had been removed or thrown overboard.[101]

With the Franco-Spanish fleet dispersed by the gale, Admiral Howe met with all his captains, and gave detailed instructions for ensuring the safe arrival of the transports. On 11 October the transports began entering the straits, followed by the covering fleet. Four transports successfully anchored at Gibraltar, but the remainder were carried by the strong currents into the Mediterranean. The British fleet followed them.[98] Taking advantage of a change in the wind, de Córdova's fleet sailed in pursuit, while the Spanish admiral sent his smaller vessels to shadow the British. On 13 October, the British regrouped off the Spanish coast about 50 miles east of Gibraltar. They then sailed south towards the Moroccan coast upon the approach of the allied fleet, which failed to catch up and did not take any of the British ships.[102]

Third and final relief

With a fair wind on 15 October, the British re-entered the straits and on 16–18 October successfully brought the convoy into Gibraltar—a total of 31 transport ships, which delivered vital supplies, food, and ammunition. The fleet also brought the 25th, 59th, and 97th regiments of foot, bringing the total number of the garrison to over 7,000.[103][104] The large combined Franco-Spanish fleet hovered nearby, so on 20 October the British fleet, without seriously engaging for battle, lured them away. The Franco-Spanish van opened fire as the British under Howe formed line of battle.[102] The British returned fire, while Howe signalled 'retreat all sail', making at least fourteen Franco-Spanish ships redundant. De Córdova's ships attempted to chase the British fleet, but despite his efforts the British, with copper sheathing, were able to avoid the trap.[105]

This was the final action of the siege and showed up again the dismal failure of the allied navy to stop the relief for the third time. The Spanish fleet's performance under de Córdova was the single greatest factor in the siege's failure.[106]

End of the siege

News that Gibraltar was fully resupplied with no problems for the convoy, combined with the disastrous Franco-Spanish attack of 13 September, reached London on 7 November and probably reached Paris about the same time.[105] This greatly strengthened the British hand at the peace talks which had begun already in October 1782. British diplomats steadfastly refused to part with Gibraltar, despite offers by Spain to trade most of its gains.[107] The objections of Spain ceased to be of any relevance, and the French accepted the preliminary peace treaty between Great Britain and America on 30 November, with protests but no action. The siege was continued but on 20 January 1783 preliminary treaties were signed with France and Spain.[108]

Unbeknown to negotiators at the peace table, on 1 February the garrison opened a sustained and accurate fire upon the besiegers causing some damage and inflicting casualties.[109] The following day de Crillon had received a letter informing him that the preliminaries of the general peace had been signed. Four days later a Spanish vessel flying a flag of truce brought news of the preliminary treaty, the terms of which allowed Britain to remain in possession of Gibraltar. By the end of February, French and Spanish troops retired disheartened and defeated, after three years, seven months and twelve days of conflict.[20]

Aftermath

The victorious British garrison during the three years of siege had sustained a loss of 333 killed[14] and 1008 wounded, which included 219 of the garrison's gunners.[15] Between 536[16] and 1,034 men died or were sick from disease.[17] In addition, 196 civilian employees were killed and 800 died of disease.[17] Between 12 April 1781 and 2 February 1783 Gibraltar was hit by 244,104 artillery rounds from guns ashore and 14,283 from cannon afloat.[15] The guns of the defenders had fired 200,600 rounds and British ships had hurled another 4,782 shells[16] and in total had expended 8,000 barrels of gunpowder.[14] The besiegers had lost in excess of 6,000 killed or wounded,[17] with many others sick or dead from disease. In addition many guns were destroyed, and the combined allied fleet lost a total of ten floating batteries, with one ship of the line and many gunboats captured. Together both sides fired nearly half a million rounds of shot during the Great Siege.[110] Elliot's defence of the Rock had tied down large numbers of Spanish and French naval and military resources that could have been valuable in other theatres of operations.[111] The Treaty of Paris reaffirmed previous treaties.

Despite the Spanish attempt to regain Gibraltar at the negotiating table, they ended up merely retaining Menorca and territories in Florida, though for the Spanish this was of little or no value.[112] Of interest is that an attempt to exchange Puerto Rico for Gibraltar collapsed, as it would have brought too much competition for Jamaican products into the protected British market. The final peace treaty left Gibraltar with the British.[113]

Elliot was made a Knight of the Bath and was created 1st Baron Heathfield of Gibraltar. Many British regiments engaged in the defence were given the badge of the Castle of Gibraltar with the motto "Montis Insignia Calpe", in commemoration of the gallant part they took in the "Great Siege". The failure of the floating batteries reduced General d'Arcon to despair, and he was deeply resentful of the failure for the rest of his life, printing a vindication in 1783 under the title "Mémoires pour servir à l’histoire du siège de Gibraltar, par l’auteur des batteries flottantes".[92]

Soon after the siege the town of Gibraltar was reconstructed, the defences strengthened, and bastions constructed. The tunnelling continued after the siege and a series of connecting galleries and communication tunnels to link them together with the Lines were built. By the end of the 18th century, nearly 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of tunnels had been dug.[114] Spain made no further attempt to besiege or blockade Gibraltar until May 1968, when the Spanish Government closed the frontier and started an economic blockade.

In popular culture

Literature

Baron Münchhausen recorded in the fourth version of the book by Rudolf Eric Raspe his visit to Gibraltar, arriving on board Admiral Rodney's flagship HMS Sandwich. Münchhausen writes that after seeing his ‘old friend Elliot’ he dressed as a Catholic priest and slipped over to the Spanish lines where he caused considerable damage with a bomb.[115]

Music

In 1782 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart composed Bardengesang auf Gibraltar: O Calpe! Dir donnert's am Fuße a piece of music commemorating the Great Siege.[116] Mozart was known to have a favourable view of the British.[117]

Paintings

There are numerous paintings of the siege by well known artists of the period.

Portrait of George Augustus Eliott by Sir Joshua Reynolds. National Gallery

Portrait of George Augustus Eliott by Sir Joshua Reynolds. National Gallery The Siege of Gibraltar, 1782 by George Carter, showing a catastrophic explosion of a floating battery. National Portrait Gallery

The Siege of Gibraltar, 1782 by George Carter, showing a catastrophic explosion of a floating battery. National Portrait Gallery.jpg) The Defeat of the Floating Batteries at Gibraltar, September 1782, also known as The Siege and Relief of Gibraltar, was painted in 1783 by American artist John Singleton Copley.[118] Tate Britain

The Defeat of the Floating Batteries at Gibraltar, September 1782, also known as The Siege and Relief of Gibraltar, was painted in 1783 by American artist John Singleton Copley.[118] Tate Britain View of Robert Curtis' attempts to rescue Spanish sailors during their disastrous assault. Painting by James Jefferys. Maidstone Museum & Art Gallery

View of Robert Curtis' attempts to rescue Spanish sailors during their disastrous assault. Painting by James Jefferys. Maidstone Museum & Art Gallery A 1789 work by American painter John Trumbull, The Sortie Made by the Garrison of Gibraltar, 1789 shows the 1781 sortie that the garrison made against the besiegers. Here the dying officer Don José de Barboza is in a slightly different pose to the 1788 version (in infobox), looking down instead of to the left.[119] Metropolitan Museum of Art

A 1789 work by American painter John Trumbull, The Sortie Made by the Garrison of Gibraltar, 1789 shows the 1781 sortie that the garrison made against the besiegers. Here the dying officer Don José de Barboza is in a slightly different pose to the 1788 version (in infobox), looking down instead of to the left.[119] Metropolitan Museum of Art A British caricature of the siege: The Duke de Crillon Giving Orders for the Siege of Gibraltar

A British caricature of the siege: The Duke de Crillon Giving Orders for the Siege of Gibraltar

Poetry

Alexei Tsvetkov's poem "The Rock" (Russian: Скала) was inspired by the siege.

Commemorative coin

In 2004, the Gibraltar National Mint release a commemorative coin into circulation. These coins feature on the obverse (front of the coin), a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II facing right and the lettering "ELIZABETH II GIBRALTAR" 2004, engraved by Raphael David Maklouf. On the coin's reverse, a cannon set for a downhill target and the lettering "1704 – 2004 THE GREAT SIEGE, 1779–1783 and ONE POUND" and was engraved by Philip Nathan.[120][121]

Today

The Great Siege Tunnels can today be accessed as part of the Upper Rock Nature Reserve; the exhibition includes dioramas and displays of the battle. After the siege the original cannon were replaced with more modern 64-pounder rifled muzzle loaders on iron carriages, some of which can still be seen in the tunnels.[122] The tunnels have been hugely expanded and new tunnels built to connect to the first galleries. By 1790 around 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of tunnels had been constructed inside The Rock.[123] They were again expanded during the Second World War.

Reconstruction of one of the many guns and embrasures within the Great Siege Tunnels

Reconstruction of one of the many guns and embrasures within the Great Siege Tunnels An example of Koehler's gun design is displayed in Grand Casemates Square

An example of Koehler's gun design is displayed in Grand Casemates Square General Eliott bronze bust in the Gibraltar Botanic Gardens

General Eliott bronze bust in the Gibraltar Botanic Gardens

See also

- John Drinkwater Bethune

- Capture of Gibraltar

- Siege of Gibraltar (1727)

- History of Gibraltar

References

- Syrett 2006, p. 105.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 86.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, pp. 18–22.

- Norwich 2006, p. 394.

- Montero 1860, p. 339.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 63:‘Of 7,500 men in the Gibraltar garrison in September (including 400 in hospital), some 3,430 were always on duty’

- Monti 1852, p. 133.

- Falkner 2009, p. 156.

- Montero 1860, p. 338.

- Montero 1860, p. 356.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 79.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 79 ‘some 30,000 sailors in the combined fleet’.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 49.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 89.

- A History of the late Siege of Gibraltar. The British Library. 1844. pp. 169–70.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 374.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492–2015, 4th ed. McFarland. p. 132. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- Montero 1860, p. 373.

- Drinkwater, John (an eyewitness) (1862), A history of the siege of Gibraltar, 1779–1783: With a description and account of that garrison from the earliest periods (3 ed.), Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson, p. 147

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 340.

- Faulkner p xix

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006.

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, p. 21.

- Sayer, Frederick (1862). The History of Gibraltar and of Its Political Relation to Events in Europe: From the Commencement of the Moorish Dynasty in Spain to the Last Morocco War. Saunders, Otley, and Company. p. 9.

- Richmond p.9

- Harding p. 39

- Simms p. 496

- Harvey 2001, p. 362.

- Clarfield, Gerard (1992), United States Diplomatic History: From Revolution to Empire, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- "The Great Siege of Gibraltar". The Keep Military Museum. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 33.

- Russell, Jack (1965). Gibraltar besieged, 1779–1783. Heinemann. p. 106.

- "Gates & Fortifications – King's Bastion". aboutourrock.com. Archived from the original on 1 November 2012. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 53.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 40.

- Sugden 2004, pp. 109–10.

- Harvey 2001, pp. 385–87.

- Faulkner p. 46

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 38.

- Patterson, Alfred Temple (1960). The Other Armada: The Franco-Spanish Attempt to Invade Britain in 1779. Manchester University Press. p. 217.

- "No. 12056". The London Gazette. 8 January 1780. p. 1.

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, p. 105.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 100.

- Mahan, pp. 450–51

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 103.

- Davis pp. 183–87

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 116.

- Gardiner p.177−179

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, pp. 41–42.

- Faulkner p. 53

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 186.

- Faulkner pp. 59–60

- Grant, James (1873). British battles on land and sea, Volume 2. Cassell. pp. 181–82.

- Hoock p. 114

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, pp. 52–53.

- Faulkner p. 69

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 216.

- Faulkner p. 68

- Red Plaque in Grand Casemates Square.

- Finlayson p.29

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 224.

- Gardiner p.167−170

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, p. 287.

- Howe, Henry (1858). Adventures and Achievements of Americans: A Series of Narratives Illustrating Their Heroism, Self-reliance, Genius and Enterprise. Geo. F. Tuttle. p. 632.

- Drinkwater 1862, pp. 244–46.

- Connolly, Thomas William John (1857). History of the Royal Sappers and Miners: from the formation of the Corps in March 1772, to the date when its designation was changed to that of Royal Engineers, in October 1856, Volume 1 (2 ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, and Roberts. pp. 16, 23.

- Bond, p. 25

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, pp. 64–65.

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, p. 309.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 272.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 306.

- Faulkner p. 102

- Ferreiro pp. 288–90

- Bond, pp. 28–29

- Monti 1852, p. 140.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 67.

- Faulkner p. 104

- Monti 1852, p. 138.

- Monti 1852, p. 132.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 76:'35,000 allied troops camped outside'

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 65.

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, pp. 335–38.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, pp. 69–70.

- Faulkner p. 118

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, pp. 79–80.

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, pp. 39–40.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, pp. 81–82.

- Montero 1860, pp. 365–66.

- "Bajas españolas de las baterías flotantes del ataque a Gibraltar el 13 de septiembre de 1782", Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish), Todo a Babor, retrieved 11 March 2010

- McGuffie, Tom Henderson (1965). The siege of Gibraltar, 1779–1783. British battles. B. T. Batsford. p. 164.

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, pp. 40–41.

- Sayer pp. 393–94

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 295.

- Faulkner p. 120

- Jay, William The Life of John Jay New York New York, Harper (1833), via Google Books— accessed 9 January 2008

- Syrett 2006, p. 103.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 307.

- Mackesy, p. 483

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 309.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 147.

- Drinkwater 1862, p. 157.

- Lavery pp. 78–79

- Syrett 2006, pp. 104–5.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 23.

- Falkner pp. 124–25

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 27.

- The Cambridge Modern History, pp. 6:379–380

- McGuffie, Tom Henderson (1965). The siege of Gibraltar, 1779–1783. B.T. Batsford. pp. 179–80.

- Adkins & Adkins 2017, pp. 364–65.

- Falkner p. 133

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 91.

- Lawrence S. Kaplan, "The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Historiographical Challenge," International History Review, Sept 1983, Vol. 5 Issue 3, pp 431–442

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 88.

- Hughes & Migos, p. 248

- Rudolf Erich, Raspe (1809). The Surprising Adventures of Baron Münchhausen. Oxford University. p. 25.

- "List of musicians connected to Gibraltar". Mark Sanchez. Archived from the original on 19 February 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- "Mozart's Tribute to Gibraltar". The Gibraltar Magazine. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2007.

- "Defeat of the Floating Batteries at Gibraltar". Collage. City of London. Archived from the original on 26 May 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- "The Sortie Made by the Garrison of Gibraltar, 1789". Acquired Tastes–Trumbull. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- Garcia, Richard J (2016). The Currency and Coinage of Gibraltar, 1704–2014 (PDF). Her Majesty's Government of Gibraltar. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-919663-40-1.

- Cuhaj, George S; Michael, Thomas (11 July 2011). 2012 Standard Catalog of World Coins 2001 to Dat. Krause Publications. p. 299. ISBN 9781440215759. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "History of the Tunnels". Great Siege Tunnels, Gibraltar.

- Chartrand & Courcelle 2006, p. 24.

Bibliography

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy (2017). Gibraltar: The Greatest Siege in British History. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781408708682.

- Bond, Peter (2003), "Gibraltar's Finest Hour: The Great Siege, 1779–1783", 300 Years of British Gibraltar, 1704–2004, Peter-Tan

- Chartrand, René; Courcelle, Patrice (2006). Gibraltar 1779–1783: The Great Siege. Gibraltar: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-977-6.

- Davis, Paul K (2003). Besieged: 100 Great Sieges from Jericho to Sarajevo. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195219302.

- Falkner, James (2009), Fire Over The Rock: The Great Siege of Gibraltar 1779–1783, Pen and Sword, ISBN 9781473814226

- Ferreiro, Larrie D (2016). Brothers at Arms: American Independence and the Men of France and Spain Who Saved It. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 9781101875254.

- Finlayson, Darren (2006). The fortifications of Gibraltar: 1068–1945. Oxford [u.a.]: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603016-1.

- Gardiner, Robert (1997). "Gibraltar: the second relief and after, 1781−1782". Navies and the American Revolution, 1775−1783. Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-55750-623-X.

- Harding, Richard (2010). The Emergence of Britain's Global Naval Supremacy: The War of 1739–1748. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 9781843835806.

- Harvey, Robert (2001), A Few Bloody Noses: The American War of Independence, London

- Hoock, Holger (2010). Empires of the Imagination: Politics, War, and the Arts in the British World, 1750–1850. Profile Books. ISBN 9781861978592.

- Hughes, Quentin; Migos, Athanassios (1995). Strong as the Rock of Gibraltar. Gibraltar: Exchange Publications. OCLC 48491998.

- Lavery, Brian (2015). Nelson's Victory: 250 Years of War and Peace. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781473854949.

- Mackesy, Piers (1964). The War for America: 1775–1783. Bison books. ISBN 9780803281929.

- Mahan, Arthur T (1898). Major Operations of the Royal Navy, 1762–1783. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 449. OCLC 46778589.

langara.

- Montero, Francisco Maria (1860). Historia de Gibraltar y de su campo (in Spanish). Imprenta de la Revista Médica.

- Monti, Ángel María (1852). Historia De Gibraltar: Dedicada A SS. AA. RR., Los Serenisimos Señores Infantes Duques De Montpensier. Juan Moyano. Retrieved 1 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murphy, Orville T (1982). Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes: French Diplomacy in the Age of Revolution, 1719–1787. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780873954839.

- Norwich, John Julius (2006). The Middle Sea: a history of the Mediterranean. Random House.

- Rodger, Nicholas (2006). The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain, 1649–1815. London.

- Richmond, Herbert William (2012). The Navy in the War of 1739–48: Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107690059.

- Simms, Brendan (2007). Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire, 1714–1783. Allan Lane. ISBN 978-0713-99426-1.

- Stephens, Frederic (1870). A history of Gibraltar and its sieges. Provost & Co.

- Sugden, John (2004). Nelson: A Dream of Glory. London. ISBN 022406097X. OCLC 56656695.

- Syrett, David (2006). Admiral Lord Howe: A Biography. London.

- Uxó, José Palasí (2007). Referencias en torno al bloqueo naval durante los asedios. Almoraima (in Spanish).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Great Siege of Gibraltar. |

- Knight, Roger. "Curtis, Sir Roger". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (subscription required).

.jpg)

.svg.png)