German philosophy

German philosophy, here taken to mean either (1) philosophy in the German language or (2) philosophy by Germans, has been extremely diverse, and central to both the analytic and continental traditions in philosophy for centuries, from Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz through Immanuel Kant, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Arthur Schopenhauer, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger and Ludwig Wittgenstein to contemporary philosophers. Søren Kierkegaard (a Danish philosopher) is frequently included in surveys of German (or Germanic) philosophy due to his extensive engagement with German thinkers.[1][2][3][4]

17th century

Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) was both a philosopher and a mathematician who wrote primarily in Latin and French. Leibniz, along with René Descartes and Baruch Spinoza, was one of the three great 17th century advocates of rationalism. The work of Leibniz also anticipated modern logic and analytic philosophy, but his philosophy also looks back to the scholastic tradition, in which conclusions are produced by applying reason to first principles or a priori definitions rather than to empirical evidence.

Leibniz is noted for his optimism - his Théodicée[5] tries to justify the apparent imperfections of the world by claiming that it is optimal among all possible worlds. It must be the best possible and most balanced world, because it was created by an all powerful and all knowing God, who would not choose to create an imperfect world if a better world could be known to him or possible to exist. In effect, apparent flaws that can be identified in this world must exist in every possible world, because otherwise God would have chosen to create the world that excluded those flaws.

Leibniz is also known for his theory of monads, as exposited in Monadologie. Monads are to the metaphysical realm what atoms are to the physical/phenomenal. They can also be compared to the corpuscles of the Mechanical Philosophy of René Descartes and others. Monads are the ultimate elements of the universe. The monads are "substantial forms of being" with the following properties: they are eternal, indecomposable, individual, subject to their own laws, un-interacting, and each reflecting the entire universe in a pre-established harmony (a historically important example of panpsychism). Monads are centers of force; substance is force, while space, matter, and motion are merely phenomenal.

18th century

Wolff

Christian Wolff (1679–1754) was the most eminent German philosopher between Leibniz and Kant. His main achievement was a complete oeuvre on almost every scholarly subject of his time, displayed and unfolded according to his demonstrative-deductive, mathematical method, which perhaps represents the peak of Enlightenment rationality in Germany.

Wolff was one of the first to use German as a language of scholarly instruction and research, although he also wrote in Latin, so that an international audience could, and did, read him. A founding father of, among other fields, economics and public administration as academic disciplines, he concentrated especially in these fields, giving advice on practical matters to people in government, and stressing the professional nature of university education.

Kant

.jpg)

In 1781, Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) published his Critique of Pure Reason, in which he attempted to determine what we can and cannot know through the use of reason independent of all experience. Briefly, he came to the conclusion that we could come to know an external world through experience, but that what we could know about it was limited by the limited terms in which the mind can think: if we can only comprehend things in terms of cause and effect, then we can only know causes and effects. It follows from this that we can know the form of all possible experience independent of all experience, but nothing else, but we can never know the world from the “standpoint of nowhere” and therefore we can never know the world in its entirety, neither via reason nor experience.

Since the publication of his Critique, Immanuel Kant has been considered one of the greatest influences in all of western philosophy. In the late 18th and early 19th century, one direct line of influence from Kant is German Idealism.

19th century

German idealism

German idealism was a philosophical movement that emerged in Germany in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. It developed out of the work of Immanuel Kant in the 1780s and 1790s,[6] and was closely linked both with Romanticism and the revolutionary politics of the Enlightenment. The most prominent German idealists in the movement, besides Kant, were Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762–1814), Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775–1854) and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) who was the predominant figure in nineteenth century German philosophy, and the proponents of Jena Romanticism; Friedrich Hölderlin (1770–1843), Novalis (1772–1801), and Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829).[7] August Ludwig Hülsen, Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi, Gottlob Ernst Schulze, Karl Leonhard Reinhold, Salomon Maimon, Friedrich Schleiermacher, and Arthur Schopenhauer also made major contributions.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

Johann Gottlieb Fichte

(1762-1814) Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling

(1775-1854) G. W. F. Hegel

G. W. F. Hegel

(1770-1831)

Karl Marx and the Young Hegelians

Hegel was hugely influential throughout the nineteenth century; by its end, according to Bertrand Russell, "the leading academic philosophers, both in America and Britain, were largely Hegelian".[8] His influence has continued in contemporary philosophy but mainly in Continental philosophy.

- Right Hegelians

Among those influenced by Hegel immediately after his death in 1831 two distinct groups can be roughly divided into the politically and religiously radical 'left', or 'young', Hegelians and the more conservative 'right', or 'old', Hegelians. The Right Hegelians followed the master in believing that the dialectic of history had come to an end—Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit reveals itself to be the culmination of history as the reader reaches its end. Here he meant that reason and freedom had reached their maximums as they were embodied by the existing Prussian state. And here the master’s claim was viewed as paradox, at best; the Prussian regime indeed provided extensive civil and social services, good universities, high employment and some industrialization, but it was ranked as rather backward politically compared with the more liberal constitutional monarchies of France and Britain.

Philosophers within the camp of the Hegelian right include:

- Johann Philipp Gabler

- Hermann Friedrich Wilhelm Hinrichs

- Karl Daub

- Heinrich Leo

- Leopold von Henning

- Heinrich Gustav Hotho

Other thinkers or historians who may be included among the Hegelian right, with some reservations, include:

- Johann Karl Friedrich Rosenkranz

- Eduard Gans

- Karl Ludwig Michelet

- Philip Marheineke

- Wilhelm Vatke

- Johann Eduard Erdmann

- Eduard Zeller

- Albert Schwegler

Speculative theism was an 1830s movement closely related to but distinguished from Right Hegelianism.[9] Its proponents (Immanuel Hermann Fichte (1796–1879), Christian Hermann Weisse (1801–1866), and Hermann Ulrici (1806–1884)[10] were united in their demand to recover the "personal God" after panlogist Hegelianism.[11] The movement featured elements of anti-psychologism in the historiography of philosophy.[12]

- Young Hegelians

The Young Hegelians drew on Hegel's idea that the purpose and promise of history was the total negation of everything conducive to restricting freedom and reason; and they proceeded to mount radical critiques, first of religion and then of the Prussian political system. The Young Hegelians who were unpopular because of their radical views on religion and society. They felt Hegel's apparent belief in the end of history conflicted with other aspects of his thought and that, contrary to his later thought, the dialectic was certainly not complete; this they felt was (painfully) obvious given the irrationality of religious beliefs and the empirical lack of freedoms—especially political and religious freedoms—in existing Prussian society. They rejected anti-utopian aspects of his thought that "Old Hegelians" have interpreted to mean that the world has already essentially reached perfection. They included Ludwig Feuerbach (1804–72), David Strauss (1808–74), Bruno Bauer (1809–82) and Max Stirner (1806–56) among their ranks.

Karl Marx (1818–83) often attended their meetings. He developed an interest in Hegelianism, French socialism and British economic theory. He transformed the three into an essential work of economics called Das Kapital, which consisted of a critical economic examination of capitalism. Marxism became one of the major forces on twentieth century world history.

It is important to note that the groups were not as unified or as self-conscious as the labels 'right' and 'left' make them appear. The term 'Right Hegelian', for example, was never actually used by those to whom it was later ascribed, namely, Hegel's direct successors at the Fredrick William University (now the Humboldt University of Berlin). (The term was first used by David Strauss to describe Bruno Bauer—who actually was a typically 'Left', or Young, Hegelian.)

Ludwig Feuerbach

Ludwig Feuerbach

(1804–72) David Strauss

David Strauss

(1808–74) Bruno Bauer

Bruno Bauer

(1809–82) Max Stirner

Max Stirner

(1806–56) Karl Marx

Karl Marx

(1818–83)

Schopenhauer

An idiosyncratic opponent of German idealism, particularly Hegel's thought, was Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 –1860). He was influenced by Eastern philosophy, particularly Buddhism, and was known for his pessimism. Schopenhauer's most influential work, The World as Will and Representation (1818), claimed that the world is fundamentally what we recognize in ourselves as our will. His analysis of will led him to the conclusion that emotional, physical, and sexual desires can never be fulfilled. Consequently, he eloquently described a lifestyle of negating desires, similar to the ascetic teachings of Vedanta and the Desert Fathers of early Christianity.[13]

During the endtimes of Schopenhauer's life and subsequent years after his death, post-Schopenhauerian pessimism became a rather popular "trend" in 19th century Germany.[14] Nevertheless, it was viewed with disdain by the other popular philosophies at the time, such as Hegelianism, materialism, neo-Kantianism and the emerging positivism. In an age of upcoming revolutions and exciting new discoveries in science, the resigned and a-progressive nature of the typical pessimist was seen as detriment to social development. To respond to this growing criticism, a group of philosophers greatly influenced by Schopenhauer such as Julius Bahnsen (1830–81), Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann (1842–1906), Philipp Mainländer (1841–76), and even some of his personal acquaintances developed their own brand of pessimism, each in their own unique way.[15][16]

Working in the metaphysical framework of Schopenhauer, Philipp Mainländer sees the "will" as the innermost core of being, the ontological arche. However, he deviates from Schopenhauer in important respects. With Schopenhauer the will is singular, unified and beyond time and space. Schopenhauer's transcendental idealism leads him to conclude that we only have access to a certain aspect of the thing-in-itself by introspective observation of our own bodies. What we observe as will is all there is to observe, nothing more. There are no hidden aspects. Furthermore, via introspection we can only observe our individual will. This also leads Mainländer to the philosophical position of pluralism.

Additionally, Mainländer accentuates on the idea of salvation for all of creation. This is yet another respect in which he differentiates his philosophy from that of Schopenhauer. With Schopenhauer, the silencing of the will is a rare event. The artistic genius can achieve this state temporarily, while only a few saints have achieved total cessation throughout history. For Mainländer, the entirety of the cosmos is slowly but surely moving towards the silencing of the will-to-live and to (as he calls it) "redemption".

Neo-Kantianism

Neo-Kantianism refers broadly to a revived type of philosophy along the lines of that laid down by Immanuel Kant in the 18th century, or more specifically by Schopenhauer's criticism of the Kantian philosophy in his work The World as Will and Representation, as well as by other post-Kantian philosophers such as Jakob Friedrich Fries (1773–1843) and Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776–1841).

The neo-Kantian schools tended to emphasize scientific readings of Kant, often downplaying the role of intuition in favour of concepts. However, the ethical aspects of neo-Kantian thought often drew them within the orbit of socialism, and they had an important influence on Austromarxism and the revisionism of Eduard Bernstein. The neo-Kantian school was of importance in devising a division of philosophy that has had durable influence well beyond Germany. It made early use of terms such as epistemology and upheld its prominence over ontology. By 1933 (after the rise of Nazism), the various neo-Kantian circles in Germany had dispersed.[17]

Notable neo-Kantian philosophers include;

- Eduard Zeller (1814–1908)

- Charles Bernard Renouvier (1815–1903)

- Hermann Lotze[18] (1817–1881)

- Hermann von Helmholtz (1821–1894)

- Kuno Fischer (1824–1907)

- Friedrich Albert Lange (1828–1875)

- Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911)

- African Spir (1837–1890)

- Otto Liebmann (1840–1912)

- Hermann Cohen (1842–1918)

- Alois Riehl (1844–1924)

- Wilhelm Windelband (1848–1915)

- Johannes Volkelt (1848–1930)

- Benno Erdmann (1851–1921)

- Hans Vaihinger (1852–1933)

- Paul Natorp (1854–1924)

- Émile Meyerson (1859–1933)

- Karl Vorländer (1860–1928)

- Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936)

- Ernst Troeltsch (1865–1923)

- Ernst Cassirer (1874–1945)

- Emil Lask (1875–1915)

- Richard Honigswald (1875–1947)

- Bruno Bauch (1877–1942)

- Leonard Nelson (1882–1927)

- Nicolai Hartmann (1882–1950)

- Hans Kelsen (1881–1973)

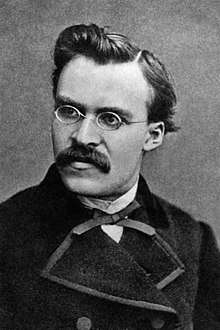

Nietzsche

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) was initially a proponent of Schopenhauer. However, he soon came to disavow Schopenhauer's pessimistic outlook on life and sought to provide a positive philosophy. He believed this task to be urgent, as he believed a form of nihilism caused by modernity was spreading across Europe, which he summed up in the phrase "God is dead". His problem, then, was how to live a positive life considering that if you believe in God, you give in to dishonesty and cruel beliefs (e.g. divine predestination of some individuals to Hell), and if you don't believe in God, you give in to nihilism. He believed he found his solution in the concepts of the Übermensch and Eternal Recurrence. His work continues to have a major influence on both philosophers and artists.

20th century

Analytic philosophy

Frege, Wittgenstein and the Vienna Circle

In the late 19th century, the predicate logic of Gottlob Frege (1848–1925) overthrew Aristotelian logic (the dominant logic since its inception in Ancient Greece). This was the beginning of analytic philosophy. In the early part of the 20th century, a group of German and Austrian philosophers and scientists formed the Vienna Circle to promote scientific thought over Hegelian system-building, which they saw as a bad influence on intellectual thought. The group considered themselves logical positivists because they believed all knowledge is either derived through experience or arrived at through analytic statements, and they adopted the predicate logic of Frege, as well as the early work of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951) as foundations to their work. Wittgenstein did not agree with their interpretation of his philosophy.

Continental philosophy

While some of the seminal philosophers of twentieth-century analytical philosophy were German-speakers, most German-language philosophy of the twentieth century tends to be defined not as analytical but 'continental' philosophy – as befits Germany's position as part of the European 'continent' as opposed to the British Isles or other culturally European nations outside of Europe.

Edmund Husserl

Edmund Husserl

(1859–1938) Karl Jaspers

Karl Jaspers

(1883–1969).jpg) Martin Heidegger

Martin Heidegger

(1889–1976) Hannah Arendt

Hannah Arendt

(1906–1975)

Phenomenology

Phenomenology began at the start of the 20th century with the descriptive psychology of Franz Brentano (1838–1917), and then the transcendental phenomenology of Edmund Husserl (1859–1938). Max Scheler (1874–1928) further developed the philosophical method of phenomenology. It was then transformed by Martin Heidegger (1889–1976), whose famous book Being and Time (1927) applied phenomenology to ontology, and who, along with Ludwig Wittgenstein, is considered one of the most influential philosophers of the 20th century. Phenomenology has had a large influence on Continental Philosophy, particularly existentialism and poststructuralism. Heidegger himself is often identified as an existentialist, though he would have rejected this.

Hermeneutics

Hermeneutics is the philosophical theory and practice of interpretation and understanding.

Originally hermeneutics referred to the interpretation of texts, especially religious texts.[19] In the 19th century, Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834), Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911) and others expanded the discipline of hermeneutics beyond mere exegesis and turned it into a general humanistic discipline.[20] Schleiermacher wondered whether there could be a hermeneutics that was not a collection of pieces of ad hoc advice for the solution of specific problems with text interpretation but rather a "general hermeneutics," which dealt with the "art of understanding" as such, which pertained to the structure and function of understanding wherever it occurs. Later in the 19th century, Dilthey began to see possibilities for continuing Schleiermacher's general hermeneutics project as a "general methodology of the humanities and social sciences".[21]

In the 20th century, hermeneutics took an 'ontological turn'. Martin Heidegger's Being and Time fundamentally transformed the discipline. No longer was it conceived of as being about understanding linguistic communication, or providing a methodological basis for the human sciences - as far as Heidegger was concerned, hermeneutics is ontology, dealing with the most fundamental conditions of man's being in the world.[22] The Heideggerian conception of hermeneutics was further developed by Heidegger's pupil Hans-Georg Gadamer (1900–2002), in his book Truth and Method.

Frankfurt School

In 1923, Carl Grünberg founded the Institute for Social Research, drawing from Marxism, Freud's psychoanalysis and Weberian philosophy, which came to be known as the "Frankfurt School". Expelled by the Nazis, the school reformed again in Frankfurt after World War II. Although they drew from Marxism, they were outspoken opponents of Stalinism. Books from the group, like Adorno’s and Horkheimer’s Dialectic of Enlightenment and Adorno’s Negative Dialectics, critiqued what they saw as the failure of the Enlightenment project and the problems of modernity. Postmodernists consider the Frankfurt school to be one of their precursors.

Since the 1960s the Frankfurt School has been guided by Jürgen Habermas' (born 1929) work on communicative reason,[23][24] linguistic intersubjectivity and what Habermas calls "the philosophical discourse of modernity".[25]

See also

- Goethe-Institut

- List of German-language philosophers

- Critical theory

- Culture of Germany

- German literature

- History of philosophy

- List of Austrian intellectual traditions

- Logical empiricism

- Modern philosophy

- Phenomenology

- Postmodernism

- Prussian virtues

References

- Lowith, Karl. From Hegel to Nietzsche, 1991, p. 370-375.

- Pinkard, Terry P. German philosophy, 1760-1860: the legacy of idealism, 2002, ch. 13.

- Stewart, Jon B. Kierkegaard and his German contemporaries, 2007

- Kenny, Anthony. Oxford Illustrated History of Western Philosophy, 2001, p.220-224.

- Rutherford (1998) is a detailed scholarly study of Leibniz's theodicy.

- Frederick C. Beiser, German Idealism: The Struggle Against Subjectivism, 1781-1801, Harvard University Press, 2002, part I.

- Frederick C. Beiser, German Idealism: The Struggle Against Subjectivism, 1781-1801, Harvard University Press, 2002, p. viii: "the young romantics—Hölderlin, Schlegel, Novalis—[were] crucial figures in the development of German idealism."

- Bertrand Russell, A History of Western Philosophy.

- Frederick C. Beiser (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Hegel, Cambridge University Press, 1993, p. 339 n. 58.

- Kelly Parker, Krzysztof Skowronski (eds.), Josiah Royce for the Twenty-first Century: Historical, Ethical, and Religious Interpretations, Lexington Books, 2012, p. 202.

- Warren Breckman, Marx, the Young Hegelians, and the Origins of Radical Social Theory: Dethroning the Self, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 49.

- William R. Woodward, Hermann Lotze: An Intellectual Biography, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 74–5.

- The World as Will and Representation, Vol. 2, Ch. 48 (Dover page 616), "The ascetic tendency is certainly unmistakable in genuine and original Christianity, as it was developed in the writings of the Church Fathers from the kernel of the New Testament; this tendency is the highest point to which everything strives upwards."

- Monika Langer, Nietzsche's Gay Science: Dancing Coherence, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 231.

- Beiser reviews the commonly held position that Schopenhauer was a transcendental idealist and he rejects it: "Though it is deeply heretical from the standpoint of transcendental idealism, Schopenhauer's objective standpoint involves a form of transcendental realism, i.e. the assumption of the independent reality of the world of experience." (Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 40).

- Beiser, Frederick C., Weltschmerz: Pessimism in German Philosophy, 1860–1900, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016, p. 213 n. 30.

- Luft 2015, p. xxvi.

- Hermann Lotze: Thought: logic and language, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- "Foundationalism and Hermeneutics". www.friesian.com. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2010-09-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2010-09-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Mantzavinos, C. (22 June 2016). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 22 March 2018 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Habermas, Jürgen. (1987). The Theory of Communicative Action. Third Edition, Vols. 1 & 2, Beacon Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen. (1990). Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action, MIT Press.

- Habermas, Jürgen. (1987). The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity. MIT Press.