Generative grammar

Generative grammar is a linguistic theory that regards linguistics as the study of a hypothesised innate grammatical structure.[3] A sociobiological[4] modification of structuralist theories, especially glossematics,[5][6] generative grammar considers grammar as a system of rules that generates exactly those combinations of words that form grammatical sentences in a given language. The difference from structural and functional models[7] is that the object is placed into the verb phrase in generative grammar.[8] This purportedly cognitive structure is thought of being a part of a universal grammar, a syntactic structure which is caused by a genetic mutation in humans.[9]

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

Generativists have created numerous theories to make the NP VP (NP) analysis work in natural language description. That is, the subject and the verb phrase appearing as independent constituents, and the object placed within the verb phrase. A main point of interest remains in how to appropriately analyse Wh-movement and other cases where the subject appears to separate the verb from the object.[10] Although claimed by generativists as a cognitively real structure, neuroscience has found no evidence for it.[11][12] Due to its nonstandard view of the brain, some researchers have called the scientific premises of generative grammar into question.[13]

Frameworks

There are a number of different approaches to generative grammar. Common to all is the effort to come up with a set of rules or principles that formally defines each and every one of the members of the set of well-formed expressions of a natural language. The term generative grammar has been associated with at least the following schools of linguistics:

- Transformational grammar (TG)

- Standard theory (ST)

- Extended standard theory (EST)

- Revised extended standard theory (REST)

- Principles and parameters theory (P&P)

- Monostratal (or non-transformational) grammars

- Relational grammar (RG)

- Lexical-functional grammar (LFG)

- Generalized phrase structure grammar (GPSG)

- Head-driven phrase structure grammar (HPSG)

- Categorial grammar

- Tree-adjoining grammar

- Optimality Theory (OT)

Historical development of models of transformational grammar

Although Leonard Bloomfield, whose work Chomsky rejects, saw the ancient Indian grammarian Pāṇini as an antecedent of structuralism,[14][15] Chomsky, in an award acceptance speech delivered in India in 2001, claimed "The first generative grammar in the modern sense was Panini's grammar".

Generative grammar has been under development since the late 1950s, and has undergone many changes in the types of rules and representations that are used to predict grammaticality. In tracing the historical development of ideas within generative grammar, it is useful to refer to various stages in the development of the theory.

Standard theory (1957–1965)

The so-called standard theory corresponds to the original model of generative grammar laid out by Chomsky in 1965.

A core aspect of standard theory is the distinction between two different representations of a sentence, called deep structure and surface structure. The two representations are linked to each other by transformational grammar.

Extended standard theory (1965–1973)

The so-called extended standard theory was formulated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Features are:

- syntactic constraints

- generalized phrase structures (X-bar theory)

Revised extended standard theory (1973–1976)

The so-called revised extended standard theory was formulated between 1973 and 1976. It contains

- restrictions upon X-bar theory (Jackendoff (1977)).

- assumption of the complementizer position.

- Move α

Relational grammar (ca. 1975–1990)

An alternative model of syntax based on the idea that notions like subject, direct object, and indirect object play a primary role in grammar.

Government and binding/Principles and parameters theory (1981–1990)

Chomsky's Lectures on Government and Binding (1981) and Barriers (1986).

Minimalist program (1990–present)

The minimalist program is a line of inquiry that hypothesizes that the human language faculty is optimal, containing only what is necessary to meet humans' physical and communicative needs, and seeks to identify the necessary properties of such a system. It was proposed by Chomsky in 1993.[16]

Context-free grammars

Generative grammars can be described and compared with the aid of the Chomsky hierarchy (proposed by Chomsky in the 1950s). This sets out a series of types of formal grammars with increasing expressive power. Among the simplest types are the regular grammars (type 3); Chomsky claims that these are not adequate as models for human language, because of the allowance of the center-embedding of strings within strings, in all natural human languages.

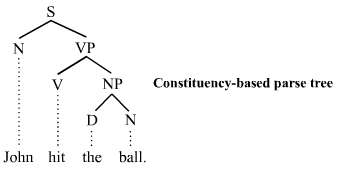

At a higher level of complexity are the context-free grammars (type 2). The derivation of a sentence by such a grammar can be depicted as a derivation tree. Linguists working within generative grammar often view such trees as a primary object of study. According to this view, a sentence is not merely a string of words. Instead, adjacent words are combined into constituents, which can then be further combined with other words or constituents to create a hierarchical tree-structure.

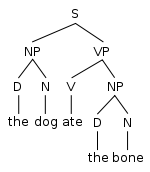

The derivation of a simple tree-structure for the sentence "the dog ate the bone" proceeds as follows. The determiner the and noun dog combine to create the noun phrase the dog. A second noun phrase the bone is created with determiner the and noun bone. The verb ate combines with the second noun phrase, the bone, to create the verb phrase ate the bone. Finally, the first noun phrase, the dog, combines with the verb phrase, ate the bone, to complete the sentence: the dog ate the bone. The following tree diagram illustrates this derivation and the resulting structure:

Such a tree diagram is also called a phrase marker. They can be represented more conveniently in text form, (though the result is less easy to read); in this format the above sentence would be rendered as:

[S [NP [D The ] [N dog ] ] [VP [V ate ] [NP [D the ] [N bone ] ] ] ]

Chomsky has argued that phrase structure grammars are also inadequate for describing natural languages, and formulated the more complex system of transformational grammar.[17]

Criticism

Lack of evidence

Noam Chomsky, the creator of generative grammar, believed to have found linguistic evidence that syntactic structures are not learned but ‘acquired’ by the child from universal grammar. This led to the establishment of the poverty of the stimulus argument. It was later found, however, that Chomsky's linguistic analysis was inadequate.[18]

There is no evidence that syntactic structures are innate. While some hopes were raised at the discovery of the FOXP2 gene,[19][20] there is not enough support for the idea that it is 'the grammar gene' or that it had much to do with the relatively recent emergence of syntactical speech.[21]

Neuroscientific studies using ERPs have found no scientific evidence for the claim that human mind processes grammatical objects as if they were placed inside the verb phrase.[11] Consequently, it is stated that generative grammar is not a useful model for neurolinguistics.[12]

Generativists also claim that language is placed inside its own mind module and that there is no interaction between first-language processing and other types of information processing, such as mathematics. This claim is not based on research or the general scientific understanding of how the brain works.[13][22]

Chomsky has answered the criticism by emphasising that his theories are actually counter-evidential. He however believes it to be a case where the real value of the research is only understood later on, as it was with Galileo.[23]

Music

Generative grammar has been used to a limited extent in music theory and analysis since the 1980s.[24][25] The most well-known approaches were developed by Mark Steedman[26] as well as Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff,[27] who formalized and extended ideas from Schenkerian analysis.[28] More recently, such early generative approaches to music were further developed and extended by various scholars.[29][30][31][32] The theory of generative grammar has been manipulated by the Sun Ra Revival Post-Krautrock Archestra in the development of their post-structuralist lyrics. This is particularly emphasised in their song "Sun Ra Meets Terry Lee". French Composer Philippe Manoury applied the systematic of generative grammar to the field of contemporary classical music.

See also

References

- Schäfer, Roland (2016). Einführung in die grammatische Beschreibung des Deutschen (2nd ed.). Berlin: Language Science Press. ISBN 978-1-537504-95-7.

- Butler, Christopher S. (2003). Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1 (PDF). John Benjamins. pp. 121–124. ISBN 9781588113580. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

- Everaert, Martin; Huybregts, Marinus A. C.; Chomsky, Noam; Berwick, Robert C.; Bolhuis, Johan J. (2015). "Structures, not strings: linguistics as part of the cognitive sciences" (PDF). Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 19 (12): 729–743. Retrieved 2020-01-05.

- Johnson, Steven (2002). "Sociobiology and you". The Nation (November 18). Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- Hjelmslev, Louis (1969) [First published 1943]. Prolegomena to a Theory of Language. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299024709.

- Seuren, Pieter A. M. (1998). Western linguistics: An historical introduction. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 160--167. ISBN 0-631-20891-7.CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Butler, Christopher S. (2003). Structure and Function: A Guide to Three Major Structural-Functional Theories, part 1 (PDF). John Benjamins. pp. 121–124. ISBN 9781588113580. Retrieved 2020-01-19.

- Osborne, Timothy (2015). "Dependency Grammar". In Kiss, Tibor; Alexiadou, Artemis (eds.). Syntax – Theory and Analysis. 2. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110358667.

- Berwick, Robert C.; Chomsky, Noam (2015). Why Only Us: Language and Evolution. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262034241.

- Kiss, Tibor; Alexiadou, Artemis, eds. (2015). Syntax--theory and analysis: An international handbook. De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110202762.

- Kluender, R.; Kutas, M. (1993). "Subjacency as a processing phenomenon" (PDF). Language and Cognitive Processes. 8 (4): 573–633. doi:10.1080/01690969308407588. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Barkley, C.; Kluender, R.; Kutas, M. (2015). "Referential processing in the human brain: An Event-Related Potential (ERP) study" (PDF). Brain Research. 1629: 143–159. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2015.09.017. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Schwarz-Friesel, Monika (2012). "On the status of external evidence in the theories of cognitive linguistics". Language Sciences. 34 (6): 656–664. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2012.04.007.

- Bloomfield, Leonard, 1929, 274; cited in Rogers, David, 1987, 88

- Hockett, Charles, 1987, 41

- Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. MIT occasional papers in linguistics no. 1. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Distributed by MIT Working Papers in Linguistics.

- Chomsky, Noam (1956). "Three models for the description of language" (PDF). IRE Transactions on Information Theory. 2 (3): 113–124. doi:10.1109/TIT.1956.1056813. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-09-19.

- Pullum, GK; Scholz, BC (2002). "Empirical assessment of stimulus poverty arguments" (PDF). The Linguistic Review. 18 (1–2): 9–50. doi:10.1515/tlir.19.1-2.9. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Scharff C, Haesler S (December 2005). "An evolutionary perspective on FoxP2: strictly for the birds?". Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 15 (6): 694–703. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2005.10.004. PMID 16266802.

- Scharff C, Petri J (July 2011). "Evo-devo, deep homology and FoxP2: implications for the evolution of speech and language". Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 366 (1574): 2124–40. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0001. PMC 3130369. PMID 21690130.

- Diller, Karl C.; Cann, Rebecca L. (2009). Rudolf Botha; Chris Knight (eds.). Evidence Against a Genetic-Based Revolution in Language 50,000 Years Ago. The Cradle of Language. Oxford Series in the Evolution of Language. Oxford.: Oxford University Press. pp. 135–149. ISBN 978-0-19-954586-5. OCLC 804498749.

- Elsabbagh, Mayada; Karmiloff-Smith, Annette (2005). "Modularity of mind and language". In Brown, Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (PDF). Elsevier. ISBN 9780080547848. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- Chomsky, Noam; Belletti, Adriana; Rizzi, Luigi (January 1, 2001). "Chapter 4: An interview on minimalism". In Chomsky, Noam (ed.). On Nature and Language (PDF). Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–161. ISBN 9780511613876. Retrieved 2020-02-28.

- Baroni, M., Maguire, S., and Drabkin, W. (1983). The Concept of Musical Grammar. Music Analysis, 2:175–208.

- Baroni, M. and Callegari, L. (1982) Eds., Musical grammars and computer analysis. Leo S. Olschki Editore: Firenze, 201–218.

- Steedman, M.J. (1989). "A Generative Grammar for Jazz Chord Sequences". Music Perception. 2 (1): 52–77. doi:10.2307/40285282. JSTOR 40285282.

- Lerdahl, Fred; Ray Jackendoff (1996). A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-62107-6.

- Heinrich Schenker, Free Composition. (Der Freie Satz) translated and edited by Ernst Ostler. New York: Longman, 1979.

- Tojo, O. Y. & Nishida, M. (2006). Analysis of chord progression by HPSG. In Proceedings of the 24th IASTED international conference on Artificial intelligence and applications, 305–310.

- Rohrmeier, Martin (2007). A generative grammar approach to diatonic harmonic structure. In Spyridis, Georgaki, Kouroupetroglou, Anagnostopoulou (Eds.), Proceedings of the 4th Sound and Music Computing Conference, 97–100. http://smc07.uoa.gr/SMC07%20Proceedings/SMC07%20Paper%2015.pdf

- Giblin, Iain (2008). Music and the generative enterprise. Doctoral dissertation. University of New South Wales.

- Katz, Jonah; David Pesetsky (2009) "The Identity Thesis for Language and Music". http://ling.auf.net/lingBuzz/000959

Further reading

- Chomsky, Noam. 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Hurford, J. (1990) Nativist and functional explanations in language acquisition. In I. M. Roca (ed.), Logical Issues in Language Acquisition, 85–136. Foris, Dordrecht.

- Isac, Daniela; Charles Reiss (2013). I-language: An Introduction to Linguistics as Cognitive Science, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953420-3.

- "Mod 4 Lesson 4.2.3 Generative-Transformational Grammar Theory". www2.leeward.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- Kamalani Hurley, Pat. "Mod 4 Lesson 4.2.3 Generative-Transformational Grammar Theory". www2.leeward.hawaii.edu. Retrieved 2017-02-02.