Übermensch

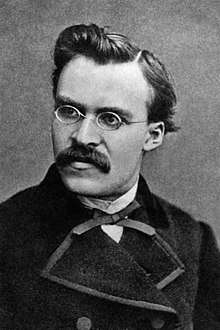

The Übermensch (German pronunciation: [ˈʔyːbɐmɛnʃ]; transl. "Beyond-Man," "Superman," "Overman," "Uberman", or "Superhuman") is a concept in the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche. In his 1883 book Thus Spoke Zarathustra (German: Also sprach Zarathustra), Nietzsche has his character Zarathustra posit the Übermensch as a goal for humanity to set for itself. It is a work of philosophical allegory, with a structural similarity to the Gathas of Zoroaster/Zarathustra.

In English

In 1896, Alexander Tille made the first English translation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, rendering Übermensch as "Beyond-Man". In 1909, Thomas Common translated it as "Superman", following the terminology of George Bernard Shaw's 1903 stage play Man and Superman. Walter Kaufmann lambasted this translation in the 1950s for two reasons: first, the failure of the English prefix "super" to capture the nuance of the German über (though in Latin, its meaning of "above" or "beyond" is closer to the German); and second, for promoting misidentification of Nietzsche's concept with the comic-book character Superman. Kaufmann and others preferred to translate Übermensch as "overman". A better translation like "superior humans" might better fit the concept of Nietzsche as he unfolds his narrative. Scholars continue to employ both terms, some simply opting to reproduce the German word.[1][2]

The German prefix über can have connotations of superiority, transcendence, excessiveness, or intensity, depending on the words to which it is attached.[3] Mensch refers to a human being, rather than a male specifically. The adjective übermenschlich means super-human: beyond human strength or out of proportion to humanity.[4]

This-worldliness

Nietzsche introduces the concept of the Übermensch in contrast to his understanding of the other-worldliness of Christianity: Zarathustra proclaims the will of the Übermensch to give meaning to life on earth, and admonishes his audience to ignore those who promise other-worldly fulfillment to draw them away from the earth.[5][6] The turn away from the earth is prompted, he says, by a dissatisfaction with life that causes the sufferer to imagine another world which will fulfill his revenge. The Übermensch grasps the earthly world with relish and gratitude.

Zarathustra declares that the Christian escape from this world also required the invention of an immortal soul separate from the earthly body. This led to the abnegation and mortification of the body, or asceticism. Zarathustra further links the Übermensch to the body and to interpreting the soul as simply an aspect of the body.[7]

Death of God and the creation of new values

Zarathustra ties the Übermensch to the death of God. While the concept of God was the ultimate expression of other-worldly values and their underlying instincts, belief in God nevertheless did give meaning to life for a time. "God is dead" means that the idea of God can no longer provide values. With the sole source of values exhausted, the danger of nihilism looms.

Zarathustra presents the Übermensch as the creator of new values to banish nihilism. If the Übermensch acts to create new values within the moral vacuum of nihilism, there is nothing that this creative act would not justify. Alternatively, in the absence of this creation, there are no grounds upon which to criticize or justify any action, including the particular values created and the means by which they are promulgated.

In order to avoid a relapse into Platonic idealism or asceticism, the creation of these new values cannot be motivated by the same instincts that gave birth to those tables of values. Instead, they must be motivated by a love of this world and of life. Whereas Nietzsche diagnosed the Christian value system as a reaction against life and hence destructive in a sense, the new values which the Übermensch will be responsible for will be life-affirming and creative (see Nietzschean affirmation).

As a goal

Zarathustra first announces the Übermensch as a goal humanity can set for itself. All human life would be given meaning by how it advanced a new generation of human beings. The aspiration of a woman would be to give birth to an Übermensch, for example; her relationships with men would be judged by this standard.[8]

Zarathustra contrasts the Übermensch with the degenerate last man of egalitarian modernity, an alternative goal which humanity might set for itself. The last man appears only in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and is presented as a smothering of aspiration antithetical to the spirit of the Übermensch.

According to Rüdiger Safranski, some commentators associate the Übermensch with a program of eugenics.[9] This is most pronounced when considered in the aspect of a goal that humanity sets for itself. The reduction of all psychology to physiology implies, to some, that human beings can be bred for cultural traits. This interpretation of Nietzsche's doctrine focuses more on the future of humanity than on a single cataclysmic individual. There is no consensus regarding how this aspect of the Übermensch relates to the creation of new values.

Re-embodiment of amoral aristocratic values

For Rüdiger Safranski, the Übermensch represents a higher biological type reached through artificial selection and at the same time is also an ideal for anyone who is creative and strong enough to master the whole spectrum of human potential, good and "evil", to become an "artist-tyrant". In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche vehemently denied any idealistic, democratic or humanitarian interpretation of the Übermensch: "The word Übermensch [designates] a type of supreme achievement, as opposed to 'modern' men, 'good' men, Christians, and other nihilists ... When I whispered into the ears of some people that they were better off looking for a Cesare Borgia than a Parsifal, they did not believe their ears."[10] Safranski argues that the combination of ruthless warrior pride and artistic brilliance that defined the Italian Renaissance embodied the sense of the Übermensch for Nietzsche. According to Safranski, Nietzsche intended the ultra-aristocratic figure of the Übermensch to serve as a Machiavellian bogeyman of the modern Western middle class and its pseudo-Christian egalitarian value system.[11]

Relation to the eternal recurrence

The Übermensch shares a place of prominence in Thus Spoke Zarathustra with another of Nietzsche's key concepts: the eternal recurrence of the same. Several interpretations for this fact have been offered.

Laurence Lampert suggests that the eternal recurrence replaces the Übermensch as the object of serious aspiration.[12] This is in part due to the fact that even the Übermensch can appear like an other-worldly hope. The Übermensch lies in the future — no historical figures have ever been Übermenschen — and so still represents a sort of eschatological redemption in some future time.

Stanley Rosen, on the other hand, suggests that the doctrine of eternal return is an esoteric ruse meant to save the concept of the Übermensch from the charge of Idealism.[13] Rather than positing an as-yet unexperienced perfection, Nietzsche would be the prophet of something that has occurred a countless number of times in the past.

Others maintain that willing the eternal recurrence of the same is a necessary step if the Übermensch is to create new values, untainted by the spirit of gravity or asceticism. Values involve a rank-ordering of things, and so are inseparable from approval and disapproval; yet it was dissatisfaction that prompted men to seek refuge in other-worldliness and embrace other-worldly values. Therefore, it could seem that the Übermensch, in being devoted to any values at all, would necessarily fail to create values that did not share some bit of asceticism. Willing the eternal recurrence is presented as accepting the existence of the low while still recognizing it as the low, and thus as overcoming the spirit of gravity or asceticism.

Still others suggest that one must have the strength of the Übermensch in order to will the eternal recurrence of the same; that is, only the Übermensch will have the strength to fully accept all of his past life, including his failures and misdeeds, and to truly will their eternal return. This action nearly kills Zarathustra, for example, and most human beings cannot avoid other-worldliness because they really are sick, not because of any choice they made.

Nazism

The term Übermensch was used frequently by Hitler and the Nazi regime to describe their idea of a biologically superior Aryan or Germanic master race;[14] a racial version of Nietzsche's Übermensch became a philosophical foundation for National Socialist ideas.[15][16] The Nazi notion of the master race also spawned the idea of "inferior humans" (Untermenschen) who should be dominated and enslaved; this term does not originate with Nietzsche, who was critical of both antisemitism and German nationalism. In his final years, Nietzsche began to believe that he was in fact Polish, not German, and was quoted as saying, "I am a pure-blooded Polish nobleman, without a single drop of bad blood, certainly not German blood".[17] In defiance of nationalist doctrines, he claimed that he and Germany were great only because of "Polish blood in their veins",[18] and that he would be "having all anti-semites shot" as an answer to his stance on anti-semitism. Nietzsche died long before Hitler's reign, and it was partly Nietzsche's sister Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche who manipulated her brother's words to accommodate the worldview of herself and her husband, Bernhard Förster, a prominent German nationalist and antisemite.[19] Förster founded the Deutscher Volksverein (German People's League) in 1881 with Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg.[20]

Anarchism

The thought of Nietzsche had an important influence on anarchist authors. Spencer Sunshine writes: "There were many things that drew anarchists to Nietzsche: his hatred of the state; his disgust for the mindless social behavior of 'herds'; his anti-Christianity; his distrust of the effect of both the market and the State on cultural production; his desire for an 'overman' — that is, for a new human who was to be neither master nor slave; his praise of the ecstatic and creative self, with the artist as his prototype, who could say, 'Yes' to the self-creation of a new world on the basis of nothing; and his forwarding of the 'transvaluation of values' as source of change, as opposed to a Marxist conception of class struggle and the dialectic of a linear history."[21] The influential American anarchist Emma Goldman, in the preface of her famous collection Anarchism and Other Essays, defends both Nietzsche and Max Stirner from attacks within anarchism when she says "The most disheartening tendency common among readers is to tear out one sentence from a work, as a criterion of the writer's ideas or personality. Friedrich Nietzsche, for instance, is decried as a hater of the weak because he believed in the Übermensch. It does not occur to the shallow interpreters of that giant mind that this vision of the Übermensch also called for a state of society which will not give birth to a race of weaklings and slaves."[22]

Sunshine says that the "Spanish anarchists also mixed their class politics with Nietzschean inspiration." Murray Bookchin, in The Spanish Anarchists, describes prominent CNT–FAI member Salvador Seguí as "an admirer of Nietzschean individualism, of the superhombre to whom 'all is permitted'." Bookchin, in his 1973 introduction to Sam Dolgoff's The Anarchist Collectives, even describes the reconstruction of society by the workers as a Nietzschean project. Bookchin says that "workers must see themselves as human beings, not as class beings; as creative personalities, not as 'proletarians,' as self-affirming individuals, not as 'masses'. . .(the) economic component must be humanized precisely by bringing an 'affinity of friendship' to the work process, by diminishing the role of onerous work in the lives of producers, indeed by a total 'transvaluation of values' (to use Nietzsche's phrase) as it applies to production and consumption as well as social and personal life."[21]

In popular culture

- The comic-book hero Superman, when Jerome "Jerry" Siegel first created him, was originally a villain modeled on Nietzsche's idea (see "The Reign of the Superman"). He was re-invented as a hero by his eventual designer, Joseph "Joe" Shuster, after which he bore little resemblance to the previous character. However, Superman does find an adversary in the mold of the Nietzschean Übermensch in the recurring arch-villain Lex Luthor, his greatest enemy on Earth. Luthor is preceded, even, by a supervillain resembling Siegel's original concept for Superman bearing the synonymous name "Ultra-Humanite". A direct reference to the term occurs in the episode "Double Trouble" of the TV series Adventures of Superman, in which a German-speaking character calls the title character "verfluchter Übermensch" ("cursed Superman").[23] In the tenth season of the show Smallville, an alternate Lionel Luthor refers to Clark as the "Übermensch". Overman is an alternate version of Superman from Earth-10, an Earth where the Axis Powers won World War II.[24]

- Jack London dedicated his novels The Sea-Wolf and Martin Eden to criticizing Nietzsche's concept of the Übermensch and his radical individualism,[25] which London considered to be selfish and egoistic.

- George Bernard Shaw's 1903 play Man and Superman is a reference to the archetype; its main character considers himself an untameable revolutionary, above the normal concerns of humanity.

- James Joyce utilizes the Übermensch in the first chapter of his novel Ulysses, in which Buck Mulligan says, "—My twelfth rib is gone, he cried. I'm the Uebermensch. Toothless Kinch and I, the supermen."[26]

- In The Power, a 1956 book by Frank M. Robinson, the villain consciously models himself upon Nietzsche's Übermensch, and a quotation from Nietzsche serves as the book's motto.

- In real life, Leopold and Loeb committed murder in 1924 partly out of a superficially Übermensch-like conception of themselves.[27] Their story has been dramatized many times, including in the Alfred Hitchcock film Rope, the 1959 film Compulsion based on Meyer Levin's novel, the 1994 film Swoon, the 2002 film Murder by Numbers, and the 2005 Off-Broadway musical Thrill Me: The Leopold and Loeb Story.

- A character in the show Dollhouse (Season 1, Episode 12; titled "Omega") references Übermensch in relation to Nietzsche when trying to describe a person that had the memories, skills, and intelligence of dozens of people uploaded into their (single) mind by means of futuristic technology.

- The Medic character in the video game Team Fortress 2 will sometimes chant "I am the Übermensch!" for one of his "Cheers" voice commands.

- In the episode "Effie Shrugged" of the Disney TV cartoon Pepper Ann, Effie, a physically imposing bully, teaches Pepper Ann some basic information about the concept of Übermensch.

- David Bowie's song titled "The Supermen", from his 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World, was inspired by the work of Nietzsche. Bowie later said "I was still going through the thing when I was pretending that I understood Nietzsche... And I had tried to translate it into my own terms to understand it so 'Supermen' came out of that."[28]

- The Avatar Press comic book series Über, written by Kieron Gillen, uses the idea in an alternate universe during World War II in which Nazi Germany creates superhuman soldiers.

- A chapter in the novel Old School by Tobias Wolff is titled "Übermensch". It humorously castigates Ayn Rand's better-and-bigger-than-life characters and satirically depicts the narrator/main character as deluded, because of Rand's The Fountainhead, in his belief that he is superior to others.

- "Übermenscher" is the name of a monster that appears in the episode "Arcadia" of the TV series The X-Files.

- The TV show Andromeda features a race of genetically engineered super-humans called Nietzscheans who follow the philosophies and teachings of Friedrich Nietzsche, Ayn Rand, Niccolò Machiavelli, and Social Darwinism. The Nietzscheans regard themselves as superior to "Kludges" (ordinary unmodified humans) and are often referred to pejoratively as "Übers" by such humans.

See also

References

Notes

- Lampert, Laurence (1986). Nietzsche's Teaching. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Rosen, Stanley (1995). The Mask of Enlightenment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Duden Deutsches Universal Wörterbuch A–Z, s.v. über-.

- Übermenschlich. PONS.eu Online Dictionary. Retrieved from http://en.pons.eu/german-english/%C3%BCbermenschlich.

- Hollingdale, R. J. (1961), page 44 – English translation of Zarathustra's prologue; "I love those who do not first seek beyond the stars for reasons to go down and to be sacrifices: but who sacrifice themselves to the earth, that the earth may one day belong to the Superman"

- Nietzsche, F. (1885) – p. 4, Original publication – "Ich liebe die, welche nicht erst hinter den Sternen einen Grund suchen, unterzugehen und Opfer zu sein: sondern die sich der Erde opfern, dass die Erde einst des Übermenschen werde."

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (2003). Thus Spoke Zarathustra. London: Penguin Books. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-140-44118-5.

- Thus Spoke Zarathustra, I.18; Lampert, Nietzsche's; Rosen, Mask of Enlightenment, 118.

- Safranski, Nietzsche, 262-64, 266–68.

- Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, Why I Write Such Good Books, §1)

- Safranski, Nietzsche, 365

- Lampert, Nietzsche's Teaching.

- Rosen, The Mask of Enlightenment.

- Alexander, Jeffrey (2011). A Contemporary Introduction to Sociology (2nd ed.). Paradigm. ISBN 978-1-61205-029-4.

- "Nietzsche inspired Hitler and other killers – Page 7", Court TV Crime Library

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2010-04-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Friedrich Nietzsche, "Ecce Homo: How One Becomes What One Is"

- Henry Louis Mencken, "The Philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche", T. Fisher Unwin, 1908, reprinted by University of Michigan 2006, pg. 6,

- Hannu Salmi (1994). "Die Sucht nach dem germanischen Ideal" (in German). Also published in Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 6/1994, pp. 485–496

- Karl Dietrich Bracher, The German Dictatorship, 1970, pp. 59–60

- "Spencer Sunshine: "Nietzsche and the Anarchists" (2005)". 18 May 2010.

- https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Anarchism_and_Other_Essays. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Grossman, Gary (1976). Superman: Serial to Cereal. New York: Popular Library. p. 67. ISBN 0445040548.

- Grant Morrison (w), Doug Mahnke (p), Christian Alamy, Rodney Ramos, Tom Nguyen, Walden Wong (i). Final Crisis: Superman Beyond 1 (October 2008), DC Comics

- Bridgwater, Patrick (1972). Nietzsche in Anglosaxony: A Study of Nietzsche's Impact on English and American Literature. Leicester: Leicester University Press. p. 169. ISBN 0718511042.

- Joyce, James (1922). Ulysses. Shakespeare & Co. ISBN 0-679-72276-9.

- "Nietzsche inspired Hitler and other killers", Court TV Crime Library

- David Buckley (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story: p.267

Bibliography

- Knoll, Manuel (2014) "The Übermensch as Social and Political Task: A Study in the Continuity of Nietzsche’s Political Thought", in: Knoll, Manual and Stocker, Barry (eds.) (2014) Nietzsche as Political Philosopher, Berlin/Boston, pp. 239–266.

- Lampert, Laurence (1986) Nietzsche's Teaching: An Interpretation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (1885) Thus Spoke Zarathustra

- Nietzsche, Friedrich; Hollingdale, R. J. and Rieu, E.V. (eds.) (1961_ Thus Spoke Zarathustra Penguin Classics: Penguin Publishing (Originally published 1885)

- Rosen, Stanley (1995) The Mask of Enlightenment: Nietzsche's Zarathustra. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Safranski, Rudiger (2002 Nietzsche: A Philosophical Biography. Translated by Shelley Frisch. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- Wilson, Colin (1981) The Outsider. Los Angeles: J.P. Tarcher.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Übermensch |

| Look up übermensch in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |