José Guadalupe Posada

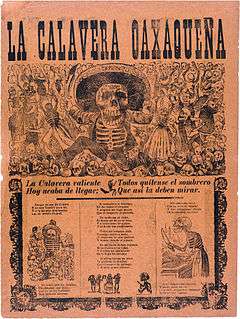

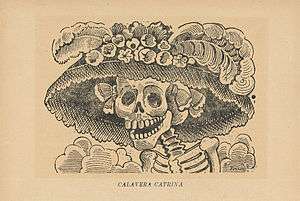

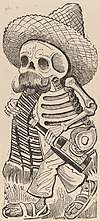

José Guadalupe Posada Aguilar (1852 – 1913) was a Mexican political lithographer who used relief printing to produce popular illustrations. His work has influenced numerous Latin American artists and cartoonists because of its satirical acuteness and social engagement. He used skulls, calaveras, and bones to convey political and cultural critiques. Among his most enduring works is La Calavera Catrina.

Early life and education

Posada was born in Aguascalientes on February 2, 1852. His father was Germán Posada Serna and his mother Petra Aguilar Portillo. Posada was one of eight children and received his early education from his older brother Cirilo, a country school teacher. Posada's brother taught him reading, writing and drawing. He then joined La Academia Municipal de Dibujo de Aguascalientes (the Municipal Drawing Academy of Aguascalientes).[1] Later, in 1868, as a teenager he apprenticed in the workshop of Jose Trinidad Pedroza, who taught him lithography and engraving. Some of Posada's first political cartoons were published in El Jicote.[2]

In 1871, before he was out of his teens, his career began with a job as the political cartoonist for a local newspaper in Aguascalientes, El Jicote ("The Bumblebee"). The newspaper closed after 11 issues, reputedly because one of Posada's cartoons had offended a powerful local politician.[3] In 1872, Posada and Pedroza dedicated themselves to commercial lithography in León, Guanajuato.[4] While in Leon, Posada opened his own workshop and worked as a teacher of lithography at the local secondary school. He also continued his work with lithographs and wood engravings. In 1873, he returned to his home in Aguascalientes City where married María de Jesús Vela in 1875. The following year he purchased the printing press from Pedroza.[5]

From 1875 to 1888, Posada continued to collaborate with several newspapers in León, including La Gacetilla, el Pueblo Caótico and La education.[6] He survived the great flood of León on June 18, 1888, of which he published several lithographs representing the tragedy in which more than two hundred and fifty corpses were found and more than 1,400 people were reported missing.[7]

At the end of 1888, he moved to Mexico City, where he learned the craft and technique of engraving in lead and zinc. He collaborated with the newspaper La Patria Ilustrada and the Revisita de Mexico until the early months of 1890.[8]

Career as artist

He began to work with Antonio Vanegas Arroyo,[9] until he was able to establish his own lithographic workshop. From then on Posada undertook work that earned him popular acceptance and admiration, for his sense of humor, and propensity concerning the quality of his work.[10] In his broad and varied work, Posada portrayed beliefs, daily lifestyles of popular groups,[11] the abuses of government and the exploitation of the common people. He illustrated the famous skulls, along with other illustrations that became popular as they were distributed to various newspapers and periodicals.[12]

In 1883, following his success, he was hired as a teacher of lithography at the local Preparatory School. The shop flourished until 1888 when a disastrous flood hit the city. He subsequently moved to Mexico City. His first regular employment in the capital was with La Patria Ilustrada, whose editor was Ireneo Paz, the grandfather of the later famed writer Octavio Paz. He later joined the staff of a publishing firm owned by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo and while at this firm he created a prolific number of book covers and illustrations. Much of his work was also published in sensationalistic broadsides depicting various current events.

From the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910 until his death in 1913, Posada worked tirelessly in the press. The works he completed in his press during this time allowed him to develop his artistic prowess as a draftsman, engraver and lithographer. At the time he continued to make satirical illustrations and cartoons featured in the magazine, El Jicote. He played a crucial role for the government during the presidency of Francisco I Madero and during the campaign of Emiliano Zapata.[13]

Notable works

Posada's best known works are his calaveras, which often assume various costumes, such as the La Calavera Catrina, she is offered as a satirical portrait of those Mexican natives who, Posada felt, were aspiring to adopt European aristocratic traditions in the pre-revolution era.

Later life

Largely forgotten by the end of his life, José Guadalupe Posada died in 1913. Three of his neighbors certified his death, only one of them knew his full name. [14]

Legacy

Academics have estimated that during his long career, Posada produced 20,000 plus images for broadsheets, pamphlets and chapbooks.[16] Posada was studied by key figures of Mexican muralism. Mural artists inspired by Posada, such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco catered to a Mexican elite that rejected foreign styles as part of their new-found bourgeois taste.[17]

In the 1920s the US and Mexico based publicist Jean Charlot popularized Posada's broadsides. In 1929 Anita Brenner published the book Idols Behind Altars, using Posada's illustrations. Brenner called Posada a prophet and linked him to the Mexica, peasants and workers.[18] The US author Frances Toor promoted Posada as folklore with her 1930 book Posada: Grabador Mexicano. Rivera commented on 406 engravings by Posada in the foreword for the book.[19]

When Leopoldo Méndez returned from the Cultural Missions programs of the Mexican Secretariat of Public Education in Jalisco, Méndez got to know about Posada's prints and adopted him as artistic and cultural hero. One of Méndez's last projects was a study of Posada, were Méndez reproduced over 900 Posada illustrations.[20]

See also

References

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 37. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 38. ISBN 9786071600752.

- History of Mexico - Mexico's Daumier: Josejhg Guadalupe Posada, Jim Tuck, Mexico Connect

- Barajas Rafael (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 49. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 50. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 52–57. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 64–70. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 70–76. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 105. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 110. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. pp. 111–112. ISBN 9786071600752.

- Rafael Barajas (2009). Myth and mitote: the political caricature of Jose Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Alfonso Manila. Fondo de Cultura Economica. p. 113. ISBN 9786071600752.

- "Fondo de Cultura Económica". fondodeculturaeconomica.

- Carlos Francisco Jackson (2009). Chicana and Chicano Art: ProtestArte. University of Arizona Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780816526475.

- Stanley Brandes (2009). Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond. John Wiley & Sons. p. 62. ISBN 9781405178709.

- Carlos Francisco Jackson (2009). Chicana and Chicano Art: ProtestArte. University of Arizona Press. p. 29. ISBN 9780816526475.

- Eric Zolov (2015). Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo. ABC-CLIO. p. 486. ISBN 9781610690447.

- Eric Zolov (2015). Iconic Mexico: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia from Acapulco to Zócalo. ABC-CLIO. p. 486. ISBN 9781610690447.

- Stanley Brandes (2009). Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead: The Day of the Dead in Mexico and Beyond. John Wiley & Sons. p. 62. ISBN 9781405178709.

- Deborah Caplow (2007). Leopoldo Méndez: Revolutionary Art and the Mexican Print. University of Texas Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780292712508.