Foreign relations of Zambia

After independence in 1964 the foreign relations of Zambia were mostly focused on supporting liberation movements in other countries in Southern Africa, such as the African National Congress and SWAPO. During the Cold War Zambia was a member of the Non-Aligned Movement.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Zambia |

|

Government |

|

Legislature |

|

|

Zambia is a member of 44 international organizations, with the United Nations, World Trade Organization, African Union and Southern African Development Community being among the most notable.

Zambia is involved in a border dispute concerning the convergence of the boundaries of Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe. An additional dispute with the Democratic Republic of Congo concerns the Lunchinda-Pweto Enclave.

History

After independence in 1964, Zambia was one of the most vocal opponents to white minority rule and colonialism. President Kenneth Kaunda, who held office 1964–1991, was a very visible advocate of change in Southern Africa. He actively supported UNITA during the Angolan liberation and civil war, SWAPO during their fight for Namibian independence from apartheid South Africa, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), and the African National Congress in their fight against apartheid in South Africa.[1]

Many of these organizations were based in Zambia during the 1970s and 1980s. For this reason South Africa as well as Rhodesia carried out military raids on targets inside Zambia. Zambia's support for the various liberation movements also caused problems for the Zambian economy, since it was heavily dependent on electricity supply and transportation through South Africa and Rhodesia. However these problems was partly solved by the Kariba Dam and the construction of the Chinese supported Tan-Zam railway.

For their part in the liberations struggles, Zambia enjoys wide popularity among the countries they supported as well as all over Africa. For instance, former South African president Nelson Mandela often referred to the debt South Africa owes Zambia.[2]

Before Zambian independence, Kaunda met with John F Kennedy while visiting the United States in 1961, and he would meet with Lyndon Johnson, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush at the White House during his long presidency.[3] He also clashed with British prime minister Margaret Thatcher on several occasions, disliking her policy towards South Africa.

As with most African states, Zambia was a member of the Non-Aligned Movement during the Cold War, and is still today. In practice Zambia was more to the left than to the right during the Cold War. The country had good relations with the People's Republic of China and with Yugoslavia. Kaunda is famous in Yugoslavia for crying openly at president Josip Broz Tito's funeral.

Kaunda's successor, president Frederick Chiluba (1991–2002), also played an important role in African politics. His government played a constructive regional role sponsoring Angola peace talks that led to the 1994 Lusaka Protocols. Zambia has provided troops to UN peacekeeping initiatives in Mozambique, Rwanda, Angola, and Sierra Leone. Zambia was the first African state to cooperate with the International Tribunal investigation of the 1994 Rwanda genocide.

In 1998, Zambia took the lead in efforts to establish a cease-fire in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Zambia was active in the Congolese peace effort after the signing of a cease-fire agreement in Lusaka in July and August 1999, although activity diminished considerably after the Joint Military Commission tasked with implementing the ceasefire relocated to Kinshasa in September 2001.

International organizations

Zambia is a member of 44 different international organisations. These are:[4]

Concerning Zambia's membership in the ICC, Zambia has a Bilateral Immunity Agreement of protection for the United States military from prosecution.

United Nations

Zambia joined the United Nations on 1 December 1964,[5] only a month after the nation had become independent. Zambia has a permanent mission to the UN, with headquarters on 237 East 52nd Street, New York City. The head of the mission is Tens Chisola Kapoma.

Regional Diplomacy

Following the independence of Zambia on October 24, 1964, the country has lent military aid and support to numerous movements and governments on the international stage. Most notably, Zambia has a history of providing military aid to combatants and political parties fighting for independence throughout Africa.[6] The aid that Zambia has provided for African nationalistic movements during the colonial era revolves around both military and diplomatic arrangement for liberation and peace.[7] The Zambian Defense Force (ZDF), which consists of the Zambian Army, Zambian Air force and Zambian National Service, has played a key part in a multitude of key regional and international conflicts throughout the 1970s and 1980s.[8] Most notably, the Zambian military has provided counter insurgent efforts during major African confrontations such as the Rhodesian Bush War despite not being the main belligerent.[9]

Zambia has a history of supporting regional liberation movements and Former President Kenneth Kaunda had previously decreed that "Zambia will not be independent and free until the rest of Africa is Free".[10] Critics have pointed to Zambia's historical stance of non-engagement and détente as a self-preservation act for a historically authoritarian government.[11] As a large central nation, the governability of Zambia relies on the stability and diplomacy of nearby states that surround Zambia.[7] Regional stability has allowed Former President Kenneth Kaunda to maintain power in the relatively poor nation for several decades.[12]

Liberation and political support

Zambia received its own liberation from colonialism relatively early from Britain. The newly formed Zambian government under President Kenneth Kaunda of the UNIP party was active in the liberation and disputes of its neighbors for decades following its independence.[13] The Zambian government offered shelter for revolutionaries, mediated treaty signings and offered aid and weapons. The continuation of colonial rule in Southern Africa was seen as a slight to Zambia and inherent feelings of African unity drove the new nation to aid its neighbors resist colonial rule.[14]

Most notably, Zambia was a haven for revolutionaries from the Namibia liberation party,[15] South West African People's Organization (SWAPO) and the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa. Zambia provided a rear base for revolutionaries as well as administrative and political aid.

SWAPO

The South West African People's Organization (SWAPO) is a political party that was formerly an independence movement based in Namibia.[16] Due to pressures from within Namibia, SWAPO moved its headquarters and much of its forces into neighboring Zambia in the 1970s. Zambia became a safe haven for the group and SWAPO set up guerrilla training camps and sent exiled members into Zambia.[15] The Shipanga Crisis, so named for senior SWAPO leader Andreas Shipanga, saw the Zambian government help round up thousands of dissidents and critics of the movement.[17] SWAPO leaders in Namibia saw growing dissent in the SWAPO installations and guerrilla camps in Zambia, and appealed to then President Kaunda for help. After rounding up thousands of perceived rebels, including Shipanga with the aid of Zambia, SWAPO leadership in Namibia became markedly more authoritarian.[18]

African National Congress

The African National Congress was an anti-apartheid political party based in South Africa, with close ideological ties to the Zambian African National Congress of President Kenneth Kaunda.[19] When the political party was banned in South Africa by the colonial government, many of its leaders went underground or fled to Zambia.[20] Lusaka, the capital of Zambia, became the new headquarters for many ANC leaders in exile from their native South Africa. Zambia thus developed a legacy of being the center of activity for South African liberation and allowed exiled leaders to convene and organize. Former South African President Nelson Mandela had expressed the important role that Zambia played in the liberation of their country during the years of exile.[21] Zambia's policy of liberation through diplomacy and discreet support for African nationalist movements within the region is most poignant in the South African case.[22]

Zimbabwe

Zambia has also provided key support to the liberation struggles of nearby Zimbabwe from their colonial rulers in the 1960s to 1970's.[23] Specifically, Zambia provided armed and diplomatic support to Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) and the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) during their struggles against the British backed Rhodesian government in the Rhodesian Bush War.[24] Zambia provided limited arms and training towards Zimbabwe's African nationalist movements, but largely applied diplomatic approaches to induce liberation in Zimbabwe.[25] This included multiple visits and discussion between the Rhodesian government and Zambia leaders to negotiate a resolution to the civil strife within the country. Eventually, in 1979, the Rhodesian government submitted to international pressures and conducted elections that lead to the eventual renaming of the country as Zimbabwe.[26]

UNITA

The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) was a party in Angola that served as one of the main belligerents in the Angolan Civil War of 1975 against People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA).[27] Zambia, under Kenneth Kaunda trained and funded UNITA against the MPLA during the civil war. Lusaka remained one of the most ardent supporters of the UNITA African nationalists and UNITA troops trained in Zambia.[28] Since then, Zambia has rescinded its historical support of UNITA and has apologized to the current Angolan government over the historical support of UNITA.[29]

Roles in regional disputes

Angolan Civil War

Zambia was key in facilitating talks between People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) of the Angolan Civil War.[30] The Angolan Civil War waged on from 1975 onward and involved massive foreign intervention in the face of the Cold War.[31] Initiated by Zambia, the Lusaka Protocol was a treaty that attempted to end the Civil War by disarmament and national reconciliation. The treaty was signed in Lusaka on November 20, 1994 and garnered international support, as well as support from Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe and South African President Nelson Mandela.[32] Ultimately the fighting resumed, and by 1998, the peace process ceased.[33]

The Second Congo War

The Second Congo war was a major African continental war that began in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1998, and involved nine different African countries.[34] Zambia was not a belligerent in this military engagement, but sought to facilitate peace and an end to the fighting. Representatives from various international organizations such as the United Nations, met on June 21–27, 1999 in Lusaka in order to draft a resolution to the conflict.[35] The ceasefire agreement set to end the fighting, deploy peacekeeping forces and release prisoners of war on both sides of the fighting. Heads of state from Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Namibia, Rwanda, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe convened in Lusaka, Zambia on July 10, 1999 to sign the Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement.[36] Ultimately hostilities continued despite the passage of the Peace Agreement, and the official fighting did not resolve itself until 2003.[37]

African cooperation

Zambia is a member of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), now known as the African Union, and was its chairman until July 2002. Zambia also takes part in the unions economical cooperation, the African Economic Community (AEC). Among th AEC's different pillars, Zambia takes part in two; Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the preferential trade area Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA). The country is also a member of the Port Management Association of Eastern and Southern Africa (PMAESA).

SADC was founded in Zambia's capital Lusaka on 1 April 1980, and COMESA has its headquarters there as well.

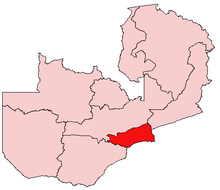

International disputes

A dormant dispute remains where Botswana, Namibia, Zambia, and Zimbabwe's boundaries converge; and with the DRC in the Lunchinda-Pweto Enclave in the North of Chienge following concerns on the Zambia-Congo Delimitation Treaty raised with the late President Laurent Kabila. The lack of demarcation beacons, and the citizenship rights of people in that enclave remain thorny issues, especially in Luapula Province.

Zambia and the Commonwealth of Nations

Zambia has been a Commonwealth republic since 24 October 1964, when Northern Rhodesia became independent.

Bilateral relations

| Country | Formal Relations Began | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1993 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations in 1993.[38] | |

| ||

| See China–Zambia relations

Both countries have diplomatic relations and cooperate in various fields.[41] | ||

| 20 September 1995 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations on 20 September 1995.[42] | |

| ||

| See Denmark-Zambia relations | ||

| 8 March 1968 |

| |

| 14 October 1993 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations on 14 October 1993. | |

| 11 February 1971 |

| |

| See India-Zambia relations | ||

| 1965 | See Ireland–Zambia relations | |

|

Both countries have a number of bilateral agreements in force.[59] | ||

| October 1964 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations in October 1964.[60] | |

| 13 July 2001 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations on 13 July 2001.[61] | |

| 15 October 1975 |

| |

| 29 June 2010 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations on 29 June 2010.[64] | |

See Namibia–Zambia relations

| ||

| ||

| 28 May 1968 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations on 28 May 1968.[66][67] | |

| 1964 | See Russia–Zambia relations

| |

| 1964 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations in 1964.[68] Both countries have passed a number of bilateral agreements.[69] | |

| See South Africa–Zambia relations

Zambia was a strong supporter of the African National Congress during their struggle against minority rule and hosted the ANC for a number of years. In 2009, nearly 52% of all goods imported to Zambia were from South Africa. | ||

|

High-level Exchanges: May 1991 Special Envoy Chung Won-shik; October 1994 Special Envoy Hong Soon-young; May 1995 Special Envoy Kim Hang-kyung; May 2010 Economic Mission Kim Jung-hoon (The Republic of Korea-Zambia business Forum).[70] | ||

| ||

| See United States–Zambia relations

Zambia, led by president Kenneth Kaunda and other diplomats such as Vernon Mwaanga, Mark Chona, and Siteke Mwale, cooperated closely with the United States between 1975 and 1984 in order to promote peaceful solutions to the conflicts in Angola, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), and Namibia.[73]

| ||

| 15 September 1972 |

Both countries established diplomatic relations on 15 September 1972.[74][75] | |

See Zambia–Zimbabwe relations

|

See also

References

- Andy DeRoche, Kenneth Kaunda, the United States and Southern Africa (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

- "Kenneth Kaunda: A life in power". BBC. 26 June 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Andy DeRoche, Kenneth Kaunda, the United States and Southern Africa (London: Bloomsbury, 2016).

- "The World Factbook – Zambia". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 1 November 2004. Retrieved 11 May 2004.

- "List of Member States". United Nations. Archived from the original on 22 October 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- Tordoff, William (1974). Politics in Zambia. North Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. 358–362.

- Shaw, Timothy M. "The foreign policy system of Zambia." African Studies Review 19.1 (1976): 31-66.

- Abrahams, Diane; Cawthra, Gavin; Williams, Rocklyn (2003). Ourselves To Know: Civil-military Relations and Defence Transformation in Southern Africa. Pretoria: Institute for Security Studies South Africa. pp. 3–6.

- Moorcraft & McLaughlin 2008, pp. 140–143

- Musonda, Emelda. “Price Zambia Paid for Africa's Liberation." Zambia Daily Mail, www.daily-mail.co.zm/price-zambia-paid-for-africas-liberation/.

- Shaw, Timothy M. "Dilemmas of Dependence and (Under) Development: conflicts and choices in Zambia's present and prospective foreign policy." Africa Today 26.4 (1979): 43-65

- Shaw, T. M., & MUGOMBA, A. T. (1977). The political economy of regional detente: Zambia and southern africa. Journal of African Studies, 4(4), 392

- Isaacman, Allen; Lalu, Premesh; Nygren, Thomas (2005). "Digitization, History, and the Making of a Postcolonial Archive of Southern African Liberation Struggles: The Aluka Project". Africa Today. 52 (2): 55–77. JSTOR 4187703.

- Taylor & Francis Group (May 2007). "Introduction: White Power, Black Nationalism and the Cold War in Southern Africa". Cold War History. 7 (2): 165–168. doi:10.1080/14682740701284090. ISSN 1468-2745.

- A., Williams, Christian (2009). "Exile History: An Ethnography of the SWAPO Camps and the Namibian Nation". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Vigne, Randolph (January 1987). "SWAPO of Namibia: A movement in exile". Third World Quarterly. 9 (1): 85–107. doi:10.1080/01436598708419963. ISSN 0143-6597.

- Leys, Colin; Saul, John S. (1994). "Liberation without Democracy? The Swapo Crisis of 1976". Journal of Southern African Studies. 20 (1): 123–147. JSTOR 2637123.

- Fivush, Robyn (February 2010). "Speaking silence: The social construction of silence in autobiographical and cultural narratives". Memory. 18 (2): 88–98. doi:10.1080/09658210903029404. ISSN 0965-8211. PMID 19565405.

- "South Africa Bans African National Congress". African American Registry. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- Macmillan, Hugh. "The African National Congress of South Africa in Zambia: The Culture of Exile and the Changing Relationship with Home, 1964-1990." Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 35, no. 2, 2009, pp. 303–329.

- "Nelson Mandela's Work and Freedom Would Have Been Difficult If Not for Zambia." New African Magazine, 31 July 2018

- Landsberg, Chris. The quiet diplomacy of liberation: International politics and South Africa's transition. Jacana Media, 2004

- Scarritt, James R., and Solomon M. Nkiwane. "Friends, neighbors, and former enemies: the evolution of Zambia-Zimbabwe relations in a changing regional context." Africa Today 43.1 (1996): 7-31.

- Chongo, Clarence. Decolonising Southern Africa: a history of Zambia's role in Zimbabwe's liberation struggle 1964-1979. Diss. University of Pretoria, 2

- Scarritt, James R., Solomon M. Nkiwane, and Henrik Sommer. "A process tracing plausibility probe of uneven democratization's effects on cooperative dyads: The case of Zambia and Zimbabwe 1980–1993." International Interactions26.1 (2000): 55-90.

- "Insurgency in Rhodesia, 1957–1973: An Account and Assessment". International Institute for Strategic Studies. 1973.

- "Absolute Hell Over There". TIME Magazine. 17 January 1977. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Wade. "The Angolan Civil War (1975-2002): A Brief History." South African History Online, 13 July 2017

- Simuchoba, Arthur. "We Are so Sorry, Sata Tells Angola." TimesLIVE, TimesLIVE, www.timeslive.co.za/news/africa/2011-10-31-we-are-so-sorry-sata-tells-angola/.

- Vines, Alex. Angola Unravels: The Rise and Fall of the Lusaka Peace Process, 1999. Human Rights Watch.

- "AfricanCrisis". AfricanCrisis. Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2018.

- "IV. THE LUSAKA PEACE PROCESS." Human Rights Watch, www.hrw.org/reports/1999/angola/Angl998-04.htm.

- Vines, Alex (1999). Angola Unravels: The Rise and Fall of the Lusaka Peace Process. Human Rights Watch.

- Bowers, Chris (24 July 2006). "World War Three". My Direct Democracy. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018.

- "DR Congo: Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2018-11-20.

- Ngolet F. (2011) The Lusaka Ceasefire Agreement. In: Crisis in the Congo. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

- Soderlund, Walter C.; DonaldBriggs, E.; PierreNajem, Tom; Roberts, Blake C. (2013-01-01). Africa's Deadliest Conflict: Media Coverage of the Humanitarian Disaster in the Congo and the United Nations Response, 1997–2008. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 9781554588787.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 February 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 26 February 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.worldembassyinformation.com/embassy-of-zambia/denmark.html

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Indian High Commission in Lusaka

- Indian mission in Zambia

- Zambian Embassy in India

- Zambian Embassy in India contact info

- Irish embassy in Lusaka Archived 2 August 2012 at Archive.today

- Zambian high commission in London

- Embassy of Mexico in South Africa

- Embassy of Zambia in the United States

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.mofa.go.kr/ENG/countries/middleeast/countries/20070824/1_24463.jsp?menu=m_30_50

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Andy DeRoche, Kenneth Kaunda, the United States and Southern Africa (London: Bloomsbury, 2016)

- Africa Today Friends, neighbors, and former enemies: the evolution of Zambia-Zimbabwe relations in a changing regional context.(Southern Africa in the Postapartheid Era) by Scarritt, James R. ; Nkiwane, Solomon M.; published 01-JAN-96

- "Zimbabwe's neighbours", BBC, June 2008

- Zambia protests against Zimbabwe

- "Permanent Mission of The Republic of Zambia to The United Nations". Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- "Background Note: Zambia". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- "Kenneth Kaunda: A life in power". BBC. 26 June 2006. Retrieved 22 October 2006.