European jackal

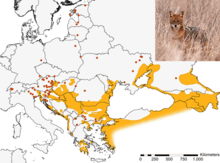

The European jackal (Canis aureus moreoticus), also known as the Caucasian jackal[2] or reed wolf[3] is a subspecies of golden jackal native to Southeast Europe, Asia Minor and the Caucasus. It was first described in 1833 by French naturalist Isidore Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire during the Morea expedition.[4] In Europe, there are an estimated 70,000 jackals.[5] Though mostly found in scattered populations within Eastern Europe, its range has grown to encompass parts of its former Eastern European range, as well as in Western Europe, which is thought to be attributable to a decline in grey wolf populations.[6][7][8]

| European jackal | |

|---|---|

_Golden_jackal_2_(cropped).png) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | C. a. moreoticus |

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis aureus moreoticus | |

| |

| Range map | |

| Synonyms | |

|

C. a. graecus (Wagner, 1841) | |

Physical description

The European jackal is the largest of the golden jackals, with animals of both sexes measuring 120–125 cm (47–49 in) in total length and 10–13 kg (20–29 lb) in body weight.[8] One adult male in North-Eastern Italy is recorded to have reached 14.9 kg (33 lb).[9] The fur is coarse, and is generally brightly coloured with blackish tones on the back. The thighs, upper legs, ears and forehead are bright reddish chestnut.[2] Jackals in Northern Dalmatia have broader than average skulls, which is thought to result from human induced isolation from other populations, thus resulting in a new morphotype.[10]

Diet

In the Caucasus, jackals mainly hunt hares, small rodents, pheasants, partridges, ducks, coots, moorhens and passerines. They readily eat lizards, snakes, frogs, fish, molluscs and insects. During the winter period, they will kill many nutrias and waterfowl. During such times, jackals will surplus kill and cache what they do not eat. Jackals will feed on fruits such as pears, hawthorn, dogwood and the cones of Common Medlars.[2] European jackals tend not to be as damaging to livestock as wolves and red foxes are, though they can become a serious nuisance to small sized stock when in high numbers.[8] The highest number of livestock damages occurred in southern Bulgaria: 1,053 attacks on small stock, mainly sheep and lambs, were recorded between 1982–87, along with some damages to newborn deer in game farms.

In Greece, rodents, insects, carrion, and fruits comprise the jackal's diet, though they rarely eat garbage, due to large numbers of stray dogs preventing them access to places with high human density.[8] Jackals in Turkey have been known to eat the eggs of the endangered green sea-turtle.[11] In Hungary, their most frequent prey are common voles and bank voles.[12] In Dalmatia, mammals (the majority being even-toed ungulates and lagomorphs) made up 50.3% of the golden jackal's diet, fruit seeds (14% each being common fig and common grape vine, while 4.6% are Juniperus oxycedrus) and vegetables 34.1%, insects (16% orthopteras, 12% beetles, and 3% dictyopteras) 29.5%, birds and their eggs 24.8%, artificial food 24%, and branches, leaves, and grass 24%.[13] Information on the diet of jackals in North-Eastern Italy is scant, but it is certain that they prey on small roe deer and hares.[9]

Distribution

The jackal's current European range mostly encompasses the Balkan region, where habitat loss and mass poisoning caused it to become extinct in many areas during the 1960s, with core populations only occurring in scattered regions such as Strandja, the Dalmatian Coast, Aegean Macedonia and the Peloponnese. It recolonised its former territories in Bulgaria during 1962, following legislative protection, and subsequently expanded its range into Romania and Serbia. Individual jackals further expanded into Italy, Slovenia, Austria, Hungary and Slovakia during the 1980s.[14] The golden jackal is listed as an Annex V species in the EU Habitats Directive and as such has legal protection in Estonia, Greece and all other EU member states.

Bulgaria has the largest jackal population in Europe, which went through a 33–fold increase in range from the early sixties to mid-eighties. Factors aiding this increase include the replacement of natural forests with dense scrub, an increase in animal carcasses from state game farms, reductions in wolf populations and the abandonment of poisoning campaigns. In the early 1990s, it was estimated that up to 5000 jackals populated Bulgaria. The population increased in 1994, and appears to have stabilised.[15]

In Greece, golden jackals are the rarest of the three wild extant canids there, having disappeared from Central Greece, Western Greece and Corfu and are now limited to discontinuous, isolated population clusters in Peloponnese, Phocis, Samos Island, Halkidiki and North-eastern Greece. Currently, the largest population cluster is located in Nestos, north-eastern Greece. Although listed as "vulnerable" in the Red Data Book for Greek Vertebrates, the species has neither been officially declared as a game species nor as a protected one.[16]

Jackal populations have been increasing in Serbia since the late 1970s, and occur mainly in north-eastern Serbia and lower Srem. Jackals are especially common near Negotin and Bela Palanka (close to the border with Bulgaria), where during the 1990s, about 500 specimens were shot.[15] In Croatia, a 2007 survey reported 19 jackal packs in the north-western part of Ravni kotari and two on Vir Island.[17] In Bosnia and Herzegovina, jackals were a rare species (from 1920 to 1999 only a few observations in the south of the country) but at the beginning of this century their significant presence in the north of the country is an obvious example of expansion of the jackals on the European continent.[18] Golden jackals are listed as a protected species in Slovenia, where they were first spotted in 1952 and have also established permanent territories there.[19] In 2005, a probably vagrant female was accidentally shot near Gornji Grad in the Upper Savinja Valley, Northern Slovenia.[6] In 2009, two territorial groups of golden jackal were recorded in the Ljubljana Marshes area, Central Slovenia. It seems that the species continues to expand towards Central Europe.[19] Jackal populations in Albania however are on the verge of extinction with possible occurrence in only three lowland wetland locations along the Adriatic Sea.[15]

_into_Poland-_first_records_-_fig._4.gif)

In Hungary, where they are sometimes called "reed wolves",[3] golden jackals had disappeared in the 1950s through hunting and habitat destruction, only to return in the late 1970s, with the first breeding pairs being detected near the southern border in Transdanubia, then between the River Danube and Tisza. Golden jackals have increased greatly in number year by year, with some estimates indicating that they now outnumber red foxes. The sighting of a jackal near the Austrian border in the summer of 2007 indicated that they have spread throughout the country.[20][21]

In Italy the species is found in the wild in Friuli Venezia Giulia, Veneto and Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol. In the High Adriatic Hinterland, its distribution has been recently updated by Lapini et al. (2009).[22] In 1984 Canis aureus had reached the Province of Belluno, in 1985 a pack reproduced near Udine (this group was eliminated in 1987), a road-killed jackal was collected in Veneto in 1992, and their presence was then confirmed in the Province of Gorizia and in the hinterland of the Gulf of Trieste. In these cases, the specimens were usually roaming male subadults, though a family-group was discovered in Agordino in 1994.[23] A young dead female was discovered on 10 December 2009 in Carnia, indicating that the species' range has continued to expand. Moreover, in the late summer of 2009, the species was also signalled in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, where it has likely reached the Puster Valley.[24] The Italian branch of WWF estimates that jackal numbers in Italy may be underestimated.[23] The golden jackal is a protected animal in Italy.[24]

A dead adult was found close to the road near Podolí (Uherské Hradiště District) in the Czech Republic, on 19 March 2006.[25]

Recently, an isolated population was confirmed in western Estonia, much further north than their common range. Whether they were an introduced population or came through natural migration was unknown.[26] Environmental Board of Estonia classified it as an invasive species, and subject to extermination campaigns.[27] However, studies confirmed that animals reached Estonia naturally from Caucasus through Ukraine, which means they are not considered invasive species any more and are treated equally with other hunted animals.[28][29] Number of jackals has grown quickly in coastal areas of Estonia. In 2016 jackals killed over 100 sheep in Estonia and during hunting season in winter 2016/2017 32 jackals were killed. Due to quick growth of jackal population their hunting season was extended by two months for next year, up to six months in a year.[28][30]

In Turkey, Romania, the North Black Sea coast, and the Caucasus region, the status of jackals is largely unknown. There are indications of expanding populations in Romania and the north-western Black Sea coast, and reports of decline in Turkey.[15]

In Denmark the carcass of a roadkilled golden jackal was discovered in September 2015 near Karup in Central Jutland.[31] In August 2016 a live golden jackal was spotted and photographed in Lille Vildmose.[32]

The species' presence in Poland was confirmed in 2015 through a necropsy on a roadkilled male found in the northwest and camera trapping of two live specimens in the east.[33]

In the Netherlands, presence of a single individual was confirmed through a camera trap at the Veluwe in 2016.[34]

A golden jackal was photographed in late 2017 in Haute-Savoie, southeastern France.[35]

There have now been repeated sightings of jackals in Austria now. For the first time tyrol, a western state in the alps where an individual has been observed [36]

Late January 2019 the authorities of the Republic and Canton of Geneva revealed the first video footage of a golden jackal in Switzerland. A camera trap caught the golden jackal in December 2018. Although there are records of golden jackal presence in Switzerland since 2011, this is the first video of this wild dog-like species.[37]

Origins and presence in European tradition

Although present in Europe, jackals are not commonly featured in European folklore or literature. In the former Greek speaking and writing parts of their distribution in the eastern Mediterranean coast were mentioned under the Greek name thos/θως till the Ottoman arrival and the use of the name tsakali/τσακάλι (from Turkish çakal). Ιn similes in the Iliad (dated around 8th century BC) they are described as tawny colored, gathering together to stalk injured by hunters animals. When the injured animal collapses the jackals devour it till some lion appears and steals their prey. The ancient Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle, in 4th century BC wrote that jackals avoid lions and dogs, but they are friendly to people, not being afraid of them. He also stated that their inner parts are identical to those of the wolf and that they change appearance from summer to winter. Hesychius of Alexandria (5th - 6th century AD) wrote that the jackal is a beast similar to the wolf.[38] Theodosius the grammarian (8th century AD) wrote that θως/jackal is a beast species and that the agile/fast persons are called θοοί/thoi.[39] With the exception of Greece were it was considered among the most common mammals, being a rare and elusive animal, the European jackal was historically often assumed to be an invasive species wherever it made its presence known: In Dalmatia, it was widely believed by the inhabitants of Korčula Island that African jackals were introduced to the island by the Republic of Venice to inflict damage on the Republic of Ragusa. When in 1929 a male jackal appeared on Premuda, the islanders believed that it was brought to the island "out of a sheer malice." An African origin for Dalmatian jackals has been proven unlikely, as their skulls bear few similarities to those of the former African golden jackals (now African golden wolves), but are similar to those of the true jackals in Asia Minor.[10] Sir William Jardine thought that jackals were first transported to Europe through the Muslim conquests.[40] However, the fossil record indicates that the golden jackal likely colonised the European continent from Asia during the Upper Holocene[6] or late Pleistocene.[22]

In 2015, during an attempt to understand the genetic identity of the rapidly expanding jackal populations in Europe, an international team of researchers examined 15 microsatellite markers and a 406 base-pair fragment of the mtDNA control region from the tissue samples of 97 specimens throughout Europe and Asia Minor. The results showed that European jackals have much lower haplotype diversity than those in Israel (where they have admixed with dogs, grey wolves and African wolves), and that they mostly descend from populations originating from the Caucasus. The highest level of haplotype diversity was found in Peloponnesian jackals, which may represent a relict population of Europe's original golden jackals prior to their extirpation elsewhere. Particular attention was paid to the genetics of Baltic jackals, as all Baltic states class the animal as an artificially introduced invasive species subject to extermination. It was found that jackals in Estonia originate from the south-eastern European population, whereas those in Lithuania are of Caucasian origin; this was concluded to render the hypothesis of an artificial introduction unlikely, and that their presence in both states was consistent with the natural northward expansion of both southeastern and eastern European populations.[41]

Surveys taken in the High Adriatic Hinterland indicate that the totality of people with first hand experience of jackals (hunters, game keepers and local people) regularly mistook red foxes affected by sarcoptic mange (or in a problematic state of moult) for golden jackals. The sighting of a true golden jackal however, was always referred to as a wolf, or a little wolf. This was verified both with photo-trapping sessions and with track studies, confirming previous observations on this matter. This erroneous and controversial perception of the golden jackal may be due to the fact that its presence is still not traditional, neither in Italian and Slovenian human culture, nor in hunting and game keeping traditions.[22]

References

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 574. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Heptner, V. & Naumov, N. P. (1988), Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol.II Part 1a, Sirenia and Carnivora (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc. USA. pp. 129-164, ISBN 1-886106-81-9

- Tamás Tóth; László Krecsák; Eleonóra Szűcs; Miklós Heltai; György Huszár (2009). "Records of the golden jackal (Canis aureus Linnaeus, 1758) in Hungary from 1800th until 2007, based on a literature survey" (PDF). North-Western Journal of Zoology. 5 (2). pp. 386–405. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2012.

- Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, I. & Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, É. (1836), Expédition scientifique de Morée, tome III, 1er partie, Levrault, pp. 19-27

- Krofel, M.; Giannatos, G.; Ćirovič, D.; Stoyanov, S.; Newsome, T. M. (2017). "Golden jackal expansion in Europe: a case of mesopredator release triggered by continent-wide wolf persecution?". The Italian Journal of Mammalogy. Hystrix. 28 (1). doi:10.4404/hystrix-28.1-11819.

- Krofel, Miha; Hubert Potočnik (2008). "First record of a golden jackal (Canis aureus) in the Savinja Valley (Northern Slovenia)" (PDF). Natura Sloveniae: Journal of Field Biology. 10 (1). pp. 57–62. ISSN 1580-0814.

- Clementi, Maria. Scoperto in Val Tagliamento lo sciacallo dorato (in Italian)

- Giannatos, G. (2004), Conservation Action Plan for the golden jackal Canis aureus L. in Greece, WWF Greece. Athens, Greece. pp. 47

- (in Italian) Lapini, L. (2003). Canis aureus (Linnaeus, 1758). In: Boitani L., Lovari S. & Vigna Taglianti A. (eds.) Fauna d’Italia. Mammalia III. Carnivora-Artiodactyla. Calderini publ., Bologna, pp. 47–58

- Krystufek, Boris; Tvrtkovic, Nikola (1990). "Variability and identity of the jackals (Canis aureus) of Dalmatia" (PDF). Ann. Naturhist. Mus. Wien. 91B: 7–25.

- Brown, L.; MacDonald, D.W. (1995). "Predation on green turtle Chelonia mydas nests by wild canids at Akyatan beach, Turkey". Biological Conservation. 71: 55–60. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(94)00020-Q.

- Lanszki, J.; Heltai, M. (2002). "Feeding habits of golden jackal and red fox in south-western Hungary during winter and spring". Mammalian Biology – Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 67 (3): 129. doi:10.1078/1616-5047-00020.

- Radović, Andreja; Kovačić, Darko (2010). "Diet composition of the golden jackal (Canis aureus L.) on the Pelješac Peninsula, Dalmatia, Croatia". Periodicum Biologorum. 112 (2): 219–224.

- Arnold, J.; Humer, A.; Heltai, M.; Murariu, D.; Spassov, N.; Hacklander, K. (2011). "Current status and distribution of golden jackal Canis aureus in Europe". Mammal Review. 42: 1–11. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2907.2011.00185.x.

- Giannatos, G., 2004. Conservation Action Plan for the golden jackal Canis aureus L. in Greece Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine. WWF Greece. Athens, Greece. pp. 47

- Giannatos, Giorgos; Marinos, Yiannis; Maragou, Panagiota; Catsadorakis, Giorgos (2005). "The status of the Golden Jackal (Canis aureus L.) in Greece" (PDF). Belg. J. Zool. 135 (2): 145–149.

- Krofel, Miha (2008). "Survey of golden jackals (Canis aureus L.) in Northern Dalmatia, Croatia: preliminary results". Natura Croatica. Croatian Natural History Museum. 17 (4): 259–264. ISSN 1330-0520. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- Trbojević, Igor; Trbojević, Tijana; Malešević, Danijela; Krofel, Miha (2018). "The golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Bosnia and Herzegovina: density of territorial groups, population trend and distribution range". Mammal Research. 63 (3): 341–348. doi:10.1007/s13364-018-0365-1.

- Krofel, Miha (2009). "Confirmed presence of territorial groups of golden jackals (Canis aureus) in Slovenia" (PDF). Natura Sloveniae: Journal of Field Biology. 11 (1). Association for Technical Culture of Slovenia. pp. 65–68. ISSN 1580-0814. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- Szabó L.; M. Heltai; J. Lanszki; E. Szőcs (2007). "An Indigenous Predator, The Golden Jackal (Canis aureus L. 1758) Spreading Like an Invasive Species in Hungary". Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Animal Science and Biotechnologies. 64 (1–2).

- Szabó, László; Heltai, Miklós; Szűcs, Eleonóra; Lanszki, József; Lehoczki, Róbert (2009). "Expansion Range of the Golden Jackal in Hungary between 1997 and 2006" (PDF). Mammalia. 73 (4). doi:10.1515/MAMM.2009.048.

- Lapini L.; Molinari P.; Dorigo L.; Are G.; Beraldo P. (2009). "Reproduction of the Golden Jackal (Canis aureus moreoticus I. Geoffroy Saint Hilaire, 1835) in Julian Pre-Alps, with new data on its range-expansion in the High-Adriatic Hinterland (Mammalia, Carnivora, Canidae)" (PDF). Boll. Mus. Civ. St. Nat. Venezia. 60: 169–186. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011.

- (in Italian) Sciacallo dorato (Canis aureus) Archived 20 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. wwf.it

- (in Italian) Lapini L., 2009–2010. Lo sciacallo dorato Canis aureus moreoticus (I. Geoffrey Saint Hilaire, 1835) nell'Italia nordorientale (Carnivora: Canidae). Tesi di Laurea in Zoologia, Fac. Di Scienze Naturali dell'Univ. di Trieste, V. Ord., relatore E. Pizzul: 1–118.

- Koubek P, Cerveny J (2007). "The Golden jackal (Canis aureus) – a new mammal species in the Czech Republic". Lynx. 38: 103–106. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- (in Estonian) Peep Männil: Läänemaal elab veel vähemalt kaks šaakalit, tõenäoliselt rohkem, Eestielu.ee (3 April 2013)

- (in Estonian) Amet: šaakalid tuleb eemaldada, EestiPäevaleht (21 May 2013)

- (in Estonian) Ivar Soopan. Jaht Läänemaal ulatuslikult levinud šaakalitele pikeneb kahe kuu võrra. Läänlane, 20 July 2017

- (in Estonian) Eesti šaakalid on pärit Kaukaasiast, Lääne Elu, 18 November 2015

- (in Estonian) Šaakalite jahihooaeg pikenes kahe kuu võrra. Postimees, 1 September 2017

- Christian W (10 September 2015). "European jackal found in Denmark". The Copenhagen Post. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- "Sensation: Vild sjakal spottet i Nordjylland". 8 August 2016. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- Kowalczyc, R.; et al. (2015). "Range expansion of the golden jackal (Canis aureus) into Poland: first records". Mammal Research. 60 (4): 411–414. doi:10.1007/s13364-015-0238-9.

- "Jakhals waargenomen op de Veluwe". nu.nl. 29 February 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- "Le chacal doré est arrivé en France !". ferus.fr. 15 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- https://wilderness-society.org/golden-jackal-spotted-in-the-austrian-alps/

- https://wilderness-society.org/golden-jackal-shows-up-in-geneva-switzerland/

- Ησύχιος Γραμματικός Αλεξανδρεύς 5th - 6th century AD: ΕΥΛΟΓΙΩΙ ΤΩΙ ΕΤΑΙΡΩΙ ΧΑΙΡΕΙΝ

- Θεοδόσιος Γραμματικός Αλεξανδρέως 8th century AD: Εισαγωγικοί κανόνες περί κλίσεως ονομάτων

- Jardine, William (1839). The naturalist's library, Volume 9, published by W.H. Lizars.

- Rutkowski R, Krofel M, Giannatos G, Ćirović D, Männil P, Volokh AM, et al. (2015) "A European Concern? Genetic Structure and Expansion of Golden Jackals (Canis aureus) in Europe and the Caucasus". PLoS ONE 10(11):e0141236. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0141236

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canis aureus moreotica. |