Eumenes

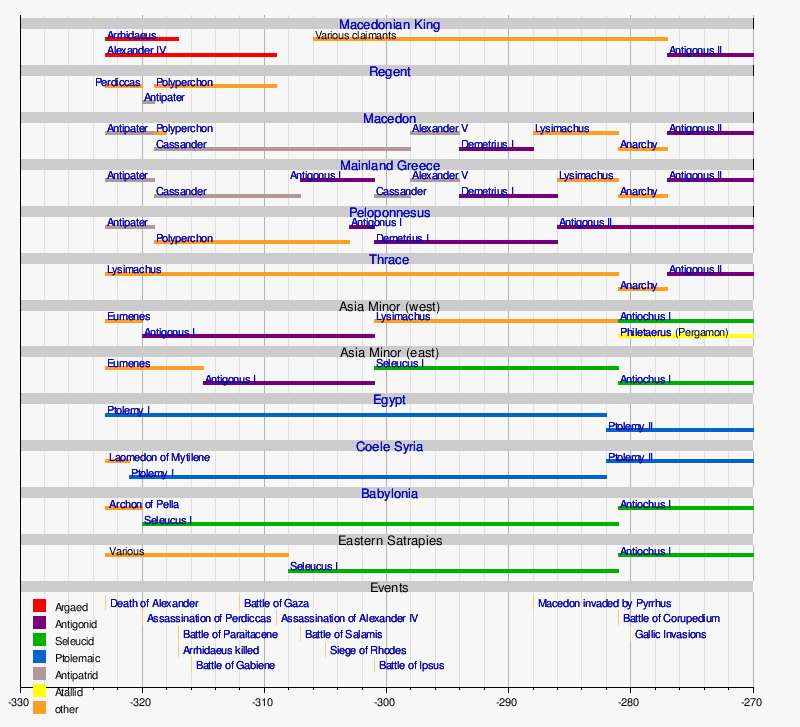

Eumenes of Cardia (/juːˈmɛniːz/; Greek: Εὐμένης; c. 362 – 316 BC) was a Greek general and satrap. He participated in the Wars of the Diadochi as a supporter of the Macedonian Argead royal house. He was executed after the Battle of Gabiene in 316 BC.

Eumenes | |

|---|---|

Eumenes of Cardia, late 17th century print. | |

| Born | Cardia (in the Thracian Chersonese) |

| Died | Gabiene (in Persia) |

| Allegiance | Macedonian Empire |

| Years of service | fl. 362 – 316 BC |

| Rank | General Satrap of Cappadocia and Paphlagonia |

| Battles/wars | First Diadochi War (322-320 BC) Battle of the Hellespont (321 BC) Battle of Orkynia (319 BC) Second Diadochi War (318-315 BC) Battle of Paraitakene (316 BC) Battle of Gabiene (315 BC) |

| Spouse(s) | Artonis, daughter of Achaemenid satrap Artabazus II |

Early career

Eumenes was a native of Cardia in the Thracian Chersonese, although he was suspected to be Scythian. At a very early age, he was employed as a private secretary by Philip II of Macedon and after Philip's death (336 BC) by Alexander the Great, whom he accompanied into Asia.[1] After Alexander's death (323 BC), Eumenes took command of a large body of Greek and Macedonian soldiers fighting in support of Alexander's son, Alexander IV.

Satrap of Cappadocia and Paphlagonia (323-319 BC)

In the ensuing division of the empire in the Partition of Babylon (323 BC), Cappadocia and Paphlagonia were assigned to Eumenes; but as they were not yet subdued, Leonnatus and Antigonus were charged by Perdiccas with securing them for him. Antigonus, however, ignored the order, and Leonnatus vainly attempted to induce Eumenes to accompany him to Europe and share in his far-reaching designs. Eumenes joined Perdiccas, who installed him in Cappadocia.[1]

Battle of the Hellespont (321 BC)

When Craterus and Antipater, having subdued Greece in the Lamian War, determined to pass into Asia and overthrow the power of Perdiccas, their first blow was aimed at Cappadocia. Craterus and Neoptolemus, the satrap of Armenia, were completely defeated by Eumenes in the Battle of the Hellespont in 321. Neoptolemus was killed, and Craterus died of his wounds.[1]

After the death of Perdiccas

After the murder of Perdiccas in Egypt by his own soldiers (320), the Macedonian generals condemned Eumenes to death, assigning Antipater and Antigonus as his executioners. In 319 BC, Antigonus marched his army into Cappadocia and, in a lightning campaign, drove Eumenes to Nora, a strong fortress on the border between Cappadocia and Lycaonia. Here Eumenes held out for more than a year until the death of Antipater threw his opponents into disarray.[1]

The Second War of the Diadochi

Antipater had left the regency to his friend Polyperchon instead of his son Cassander. Cassander, therefore, allied himself with Antigonus, Lysimachus and Ptolemy, while Eumenes allied himself with Polyperchon.[1] He was able to escape from Nora through trickery and, after gathering a small army, he marched into Cilicia where he made an alliance with Antigenes and Teutamos, the commanders of the Macedonian Silver Shields and the Hypaspists.[2] Eventually Eumenes secured control over these men by playing on their loyalty to, and superstitious awe of, Alexander.[3] He used the royal treasury at Kyinda to recruit an army of mercenaries to add to his own troops and the Macedonians of Antigenes and Teutamos.[4]

In 317 BC, Eumenes left Cilicia and marched into Syria and Phoenicia, and began to raise a naval force on behalf of Polyperchon.[5] When it was ready he sent the fleet west to reinforce Polyperchon, but it was met by Antigonus's fleet off the coast of Cilicia, and the fleet of Eumenes changed sides.[6]

Meanwhile, Antigonus had settled his affairs in Asia Minor and marched east to take out Eumenes before he could do further damage. Eumenes somehow had advance knowledge of this and marched out of Phoenica, through Syria into Mesopotamia, with the idea of gathering support in the upper satrapies.[7]

Eumenes in the East

Eumenes gained the support of Amphimachos, the satrap of Mesopotamia,[8] then marched his army into Northern Babylonia, where he put them into winter quarters. During the winter he negotiated with Seleucus, the satrap of Babylonia, and Peithon, the satrap of Media, seeking their help against Antigonus.[9] Unable to sway Seleucus and Peithon, Eumenes left his winter quarters early and marched on Susa, a major royal treasury, in Susiana.[10] In Susa, Eumenes sent letters to all the satraps to the north and east of Susiana, ordering them in the kings' names to join him with all their forces.[11] When the satraps joined Eumenes he had a considerable force, with which he could look forward with some confidence to doing battle against Antigonus.[12] Eumenes then marched southeastwards into Persia, where he picked up additional reinforcements.[13]

Antigonus, meanwhile, had reached Susa and left Seleucus there to besiege the place, while he himself marched after Eumenes. At the river Kopratas, Eumenes surprised Antigonus during the crossing of the river and killed or captured 4,000 of his men.[14] Antigonus, faced with disaster, decided to abandon the crossing and turned back northward, marching up into Media, threatening the upper satrapies.[15] Eumenes wanted to march westward and cut Antigonus's supply lines, but the satraps refused to abandon their satrapies and forced Eumenes to stay in the east.

In the late summer of 316 BC, Antigonus moved southward again in the hope of bringing Eumenes to battle and ending the war quickly. Eventually, the two armies met in southern Media and fought the indecisive Battle of Paraitakene.[16] Antigonus, whose casualties were more numerous, force marched his army to safety the next night.[17] During the winter of 316-315 BC, Antigonus tried to surprise Eumenes in Persis by marching his army across a desert and catching his enemy off guard; unfortunately, he was observed by some locals who reported it to his opponents.[18] A few days later both armies drew up for battle. The Battle of Gabiene was as indecisive as the previous battle at Parataikene.[19] According to Plutarch and Diodorus, Eumenes had won the battle but lost control of his army's baggage camp thanks to his ally Peucestas' duplicity or incompetence. In addition to all the loot of the Silver Shields (treasure accumulated over 30 years of successful warfare including gold, silver, gems and other booty), the soldiers' women and children were taken and Eumenes' army wished to negotiate their return.

Teutamus, one of their commanders, sent the request to Antigonus who responded by demanding they give him Eumenes. The Silver Shields complied, arrested Eumenes and his officers, and handed them over.[20] The war was thus at an end. Eumenes was placed under guard while Antigonus held a council to ponder his fate. Antigonus, supported by his son Demetrius, was disinclined to kill Eumenes, but most of the council insisted that he execute Eumenes and so it was decided.[21]

Death

Antigonus, according to Plutarch, starved Eumenes for three days, but finally sent an executioner to dispatch him when the time came for him to move his camp. Eumenes' body was given to his friends, to be burnt with honor, and his ashes were conveyed in a silver urn to his wife and children.[21]

Legacy

Despite Eumenes' undeniable skills as a general, he never commanded the full allegiance of the Macedonian officers in his army and died as a result. He was an able commander who did his utmost to maintain the unity of Alexander's empire in Asia, but his efforts were frustrated by generals and satraps both nominally under his command and under that of his enemies.[1] Eumenes was hated and despised by many fellow commanders—certainly for his successes and supposedly for his non-Macedonian (in the tribal sense) background and prior office as Royal Secretary. Eumenes has been seen as a tragic figure, a man who seemingly tried to do the right thing but was overcome by a more ruthless enemy and the treachery of his own soldiers.

Historie is an award-winning historical fiction manga series that tells the life story of Eumenes, in a fictional way.

Family

Pharnabazus III, Persian satrap of Phrygia, was his brother-in-law, as Eumenes married Artonis, the daughter of Persian satrap Artabazus II and sister of Pharnabazus III.

"For Barsine, the daughter of Artabazus, who was the first lady Alexander took to his bed in Asia, and who brought him a son named Heracles, had two sisters; one of which, called Apame, he gave to Ptolemy; and the other, called Artonis, he gave to Eumenes, at the time when he was selecting Persian ladies as wives for his friends."

— Plutarch, The Life of Eumenes.[22]

Sources

- Plutarch - the main surviving biography of Eumenes is by Plutarch. Plutarch's parallel Roman life was the life of Sertorius.

- Diodorus - Eumenes is a significant figure in books 16–18 of Diodorus's history

- Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State, a biography of Antigonos Monopthalmus (Eumenes's main opponent during the Second War of the Diadochi).

References

- Chisholm 1911.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 59,1-3.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 60,1-60,3.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 61,4-5

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 63,6.

- Polyainos,Strategemata IV 6,9.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 73,1-2.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XVIII 39,6 and XIX 27,4.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 12,1-2.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 12,5-13,5.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 13,6-7.

- Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State p.90.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 17,3-7.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 18,3-7; Plutarch, Life of Eumenes, 14,1-2.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 19,1-2.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 26-32,2; Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State pp.95-98.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 32,1-2

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 37,2-6; Plutarch, Life of Eumenes, 15,3-4; Polyainos, Strategemata IV 6,11 and 8,4.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 42,1-3; Plutarch, Life of Eumenes, 16,5-6; Polyainos, Strategemata IV 6,13; Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State pp.100-102.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 42,4-43,8; Plutarch, Life of Eumenes, 16,4-17,1; Polyainos, Strategemata IV 6,13; Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State p.102-103.

- Diodorus Sicilus, Bibliotheca Historica, XIX 43,8-44,3; Plutarch, Life of Eumenes, 17,1-19,1; Richard A. Billows, Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State p.104.

- Plutarch: Life of Eumenes - translation.

Sources

- Edward Anson, Eumenes of Cardia: A Greek among Macedonians, Brill Academic Publishers, 2004.

- Waterfield, Robin (2011). Dividing the Spoils - The War for Alexander the Great’s Empire (hardback). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 273 pages. ISBN 978-0-19-957392-9.